by Alex Dueben

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the comic strip Big Nate. If you’re scratching your head thinking that Lincoln Peirce couldn’t have been working on the strip that long, well, you’re not alone. Odds are that you or your kids discovered the strip in the past decade through the novels that Peirce wrote or the comic strip collections that have been one of the AMP! imprint’s flagship titles.

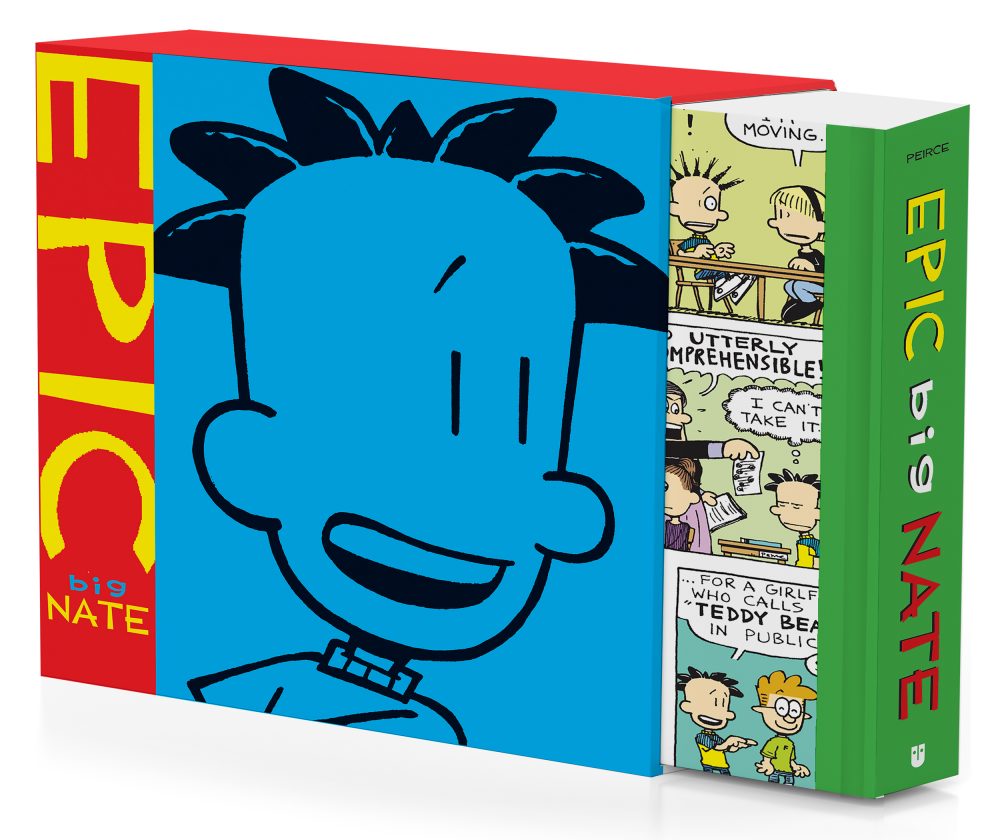

To mark the milestone, Andrews McMeel has just published The Epic Big Nate, an oversized hardcover slipcased edition with a selection of strips from throughout the run with commentary from Peirce. Like every comic, it’s evolved over the years and Peirce sat down to talk about his work and look back on what’s changed and what hasn’t.

Alex Dueben: 2016 marks the 25th Anniversary of Big Nate, and it’s interesting to think of it as this older strip because I feel like it really found its audience in the past decade.

Lincoln Peirce: Absolutely. I think that is largely due to the series of children’s books that I wrote for Harper Collins. Those books which were written specifically for children aged 7-12 so they were unlike the strip in that way. I write the strip for readers of all ages but these books were targeted specifically for kids and they really raised the profile of the strip. Kids, as you know, don’t necessarily read newspapers. [laughs] In most cases they don’t read newspaper comics–but they read books. All of a sudden a new generation of young people who had probably never heard of Big Nate got to familiarize themselves with the characters through those novels and then they said, oh, there’s a comic strip too?

Dueben: Before you started writing the novels, or got attention from them, did you feel that you had hit your stride, that you were happy with the strip creatively?

Peirce: I had sort of resigned myself to the fact that the strip was going to have a loyal following–which it did–and it was going to be a success in the sense that I was able to make a living from it and I was able to keep food on the table and keep a roof over our heads, but it was never going to be a huge breakout hit in the comics pages. I think it’s really an unlikely story that after the strip had been around for almost twenty years, it gained this second life. Up to that point I was happy with the strip and the direction it had gone in for the first couple of decades. I felt like I was really hitting my stride. The first few years of the strip I felt like I was really learning on the job and I don’t feel like I entirely knew what I was doing until I had been doing it for a number of years.

Dueben: I think that’s true of just about every comic strip.

Peirce: I think so, too. I’ve met a lot of other cartoonists and spoke with them and almost without exception most of us are at the very least a little bit sheepish about our early stuff–and at the very worst, absolutely horrified. [laughs]

Dueben: In the book’s forward, there’s a story about how Charles Schulz called you at the very beginning of your career.

Peirce: My editor at the time was a woman named Sarah Gillespie and Charles Schulz was with the same syndicate and had the same editor that I did. She had told me in advance that often times when considering whether or not to syndicate a new strip, she would send samples of it to Charles Schulz and ask him what he thought. She told me sometimes if he really likes something he might reach out. She had planted that seed, but I didn’t dare hope that he might like my stuff or call me, but in fact he did call me. It was the voice of my childhood hero on the other end of the phone and it was phenomenal.

Dueben: You write notes about some of the strips throughout the book and you comment early on that you set out to do a strip about a boy and his family, but it became a strip about a boy and his school.

Peirce: When I made my initial submission to the syndicate, most of the gags were about Nate and his dad and his sister. I thought at the time that one thing that might set my strip apart from some of the other domestic humor strips was that it was a single parent family. I thought a single father with a middle schooler and a high schooler was unique. Then once I started rolling, I realized that the jokes that I most enjoyed were all ones where Nate was in school. I’m a believer that you can do some planning in any sort of creative venture, but another force will take over. Something that you hadn’t really planned for will often happen, whether you’re making a movie or composing music or whatever it may be. I certainly think it’s true of comic strips because if you write gags and you really like the gag and the gag works, you’re going to keep writing those kinds of gags. That’s what happened to me. It was just so much easier for me and enjoyable to write gags about his classmates and his teachers than about his home life, so that’s just the direction it went in.

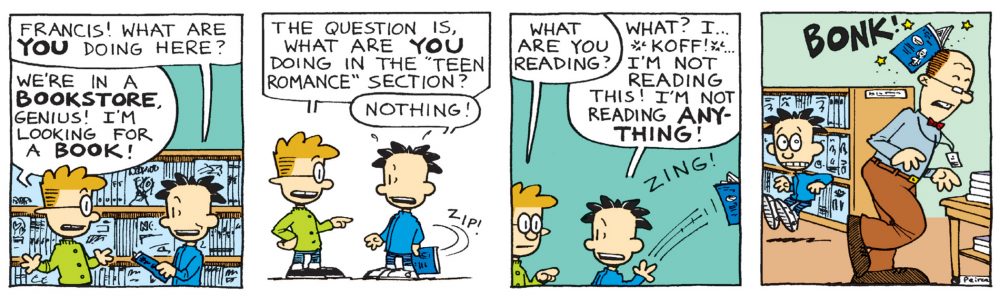

Dueben: You utilize a four panel layout all for the Big Nate dailies. Why did you settle on this and why have you kept working in that way? Because you could lay out the strip in any way you wanted.

Peirce: I could if I wanted to. I think it goes back to a couple strips I grew up with which were classic four panel strips. One was Peanuts, of course. Peanuts was four panels for the first forty years of its run and in his later years Sparky would sometimes would do different things, but there’s a rhythm to four panels that I really like. The other strip that was always a four panel strip was Doonesbury. I started reading Doonesbury almost from when it started–even though I didn’t really understand a lot of the jokes when I first started reading it. I just got accustomed to that sort of writing. Constructing a joke and writing dialogue that unfolds over four panels. Four just was perfect for me. I don’t know why, but it worked and I just stuck with it. I liked the symmetry of those four panels, identically sized, identically shaped. It just worked for me.

Dueben: One thing that distinguishes both is that they’re wordy. Doonesbury especially, and neither are gag strips. They’re based on conversational and character-based humor and that’s how you work, as well.

Peirce: I am not a joke writer. I’m the first to say that. When I talk about writing gags I don’t necessarily mean a punch line, I’m just talking about conversations where it’s the end of the conversation and for whatever reason it’s kind of amusing. I think you’re right, both those strips can be more word-heavy than a lot of strips, they’re very seldom based on visual gags or slapstick. I think you just absorb those sort of things. When you’re a young person and you’re reading as many Peanuts and Doonesbury reprint books as you could get my hands on, you absorb that rhythm.

Dueben: You still draw everything by hand and even hand letter it, is that right?

Peirce: Oh yeah. I’m a dinosaur. [laughs] I was at the Reuben Awards, which are sort of the Oscars of cartooning. We have a big weekend banquet and awards ceremony every year and this past spring it was in Memphis. There was a presentation about the Cintiq, and I was really surprised by how many of my colleagues have now gone into this entirely digitized way of producing their strip to the point where they don’t have originals any more. I understand what a time saver it can be and in many ways how much easier and more efficient it can make doing the strip. I wouldn’t call myself a luddite but from a technology standpoint, I’m behind the times. I just can’t imagine not doing the strip the old fashioned way. I enjoy sketching it out in pencil, going over it in pen, doing all the lettering by hand. I never use Photoshop or anything like that to alter the images. If I make a mistake I just patch it or use whiteout. It’s been working for me all this time so I’m just going to keep doing it that way.

Dueben: I know a number of cartoonists who draw the strip by hand but will scan it and then letter or fix mistakes on the computer, but you do everything by hand.

Peirce: I still do. The syndicate doesn’t want you to send in originals anymore so I do scan them. If there’s a smudge or a small little thing I didn’t notice as I was drawing, I can just erase it in Photoshop, but I don’t change the drawings. I don’t cut and paste. I enjoy the idea of there being a happy accident when you’re drawing.

Dueben: What do you feel is the biggest change to the strip from when you started?

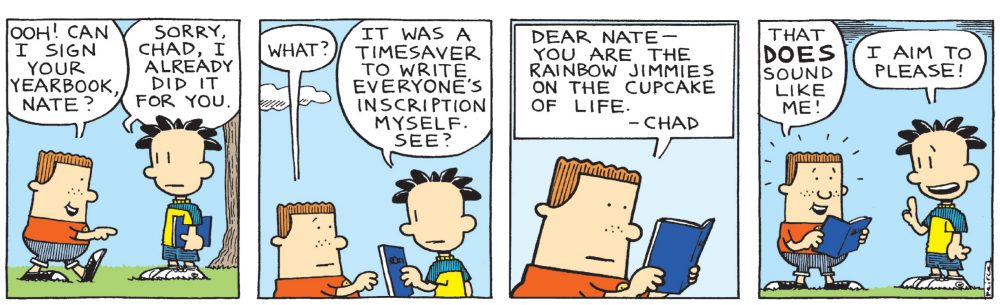

Peirce: I think my own skills have improved markedly since I started. The biggest difference to me when I look at the early strips is that the strip is a lot better now. It’s better written. I can draw much better than I could when I started. I would put that as difference number one. Difference number two–and I think this happens to any strip the longer you’re around–is the world of your strip becomes bigger because over time you introduce new characters and it just opens up a lot of other possibilities for writing storylines and writing gags. When I started the strip there were about six characters in it. I haven’t sat down and tried to count how many characters are in it now but it’s a lot and there are characters who have become hugely important parts of the strip who weren’t there when I started the strip. I look at the strip now and I see characters like Chad or Coach John or Gina, all of whom have pretty big roles to play, and none of them were there when I started it.

Dueben: As you were saying that I was thinking about Gina and Chad who have become key supporting characters to the strip.

Peirce: Absolutely. Gina was natural because I needed a nemesis for Nate. A kid who, from an academic standpoint, would be his opposite. Nate is clearly bright and creative but he’s not that motivated of a student and so it was natural of me to create a character who was Nate’s polar opposite and Gina fell into that role.

Chad is just one of my all time favorites. He’s just an innocent. He’s a late bloomer. He’s a kid who looks smaller and younger than all his classmates even though he’s the same age as all the other kids the same age around him. He’s just sweetness personified. It’s fun to have a character like that around who is not as savvy as some of the other kids, and that creates some good joke writing possibilities.

Dueben: At a certain point you introduced Nate’s grandparents, who have been a great addition.

Peirce: I love them. I think the first time I brought them in I wrote a family reunion series of strips and I thought that was fun. Maybe a year or two later I returned to them and tweaked their appearance a little bit. Readers really seemed to like them. One of the things that readers always point out is that Nate’s grandfather is the sort of person you can imagine Nate will be when he’s 80 years old. The grandfather seems like he’s a bit of a chronic screwup and a bit of a rebel himself so people can see the generational similarities there.

Maybe it’s natural as I get older that I would add in some grandparent characters. I’m not quite grandparent age yet, but it probably won’t be all that long. Something else that’s interesting too about strips that are around for a long time you sort of see the way in which the creators of the strips age. Even if the characters don’t age, you can sometimes see that the tenor and tone of a strip can change a little bit or become a little bit more nostalgic as the creators gets a little bit older.

Dueben: Along those lines, does it become more difficult writing the strip as you get older? Because you were younger and teaching when you were starting and is it a challenge now getting into Nate’s head?

Peirce: I’m not having any difficulties writing for kids or imagining and remembering what it was like to be a kid. I do think it becomes more difficult just because of the sheer number of strips you’ve drawn over the years. You just start to realize that there’s a finite number of gags out there. Sometimes it literally happens that I will write a gag and only later on realize that’s a gag I’ve written before. I think that’s the difficulty. There’s a famous quote from Sparky that doing a comic strip is basically doing the same thing every day but in a different way. I’m paraphrasing, but I think that’s largely true. You’re dealing with the same characters day after day you’re telling a lot of stories and writing a lot of gags. You’ve got to find ways to invent new situations for your characters or invent new characters so you keep it fresh. I think that’s where the difficulties come from.

Dueben: What advice would you give your younger self. You from 26 or more years ago before you came up with the idea for Big Nate but were drawing other things?

Peirce: I would have encouraged the younger me to be more diligent about practicing my writing and my drawing. I was the sort of kid who if I tried to draw a race car and it didn’t turn out perfectly, I was not the sort of kid who would try and try again until I could draw a perfect race car. I would shrug my shoulders and say, oh well, I guess I’m not very good at drawing race cars. To me, it was not all that important when I was younger to be able to draw really really well. I just wanted to be able to draw well enough to get my point across. I regretted that later because I realized in the early years of the strip that I couldn’t draw well enough to have the strip look and feel exactly the way I wanted. It took a little while before I got there.

I would give my younger self the advice to practice more and to try to stretch what it was that I was drawing. I’d invent a character, let’s say, but I’d only draw that character in the exact same way or from the exact same angle or in the exact same pose. Then all of a sudden you’re doing a daily comic strip and you think of a gag that involves Nate lying in bed or Nate riding a bicycle and you think, I’ve never drawn this. That was a challenge for me early on. I would give myself that advice to challenge myself more as a young person to really practice my craft and get better at it.

Dueben: So you’re still writing and drawing the strip seven days a week. And also working on a new novel?

Peirce: There is no next Big Nate novel. When I started the novels I signed a deal to do three of them and then we upped that six and then we upped that to eight. When I was working on the seventh and eighth ones I thought, I think this is a good time to end. I didn’t want to start repeating myself and I started to get this itch to try something a little different. The novel that came out last February, the eighth one, was the final one in the series. I’ve just started working on a new children’s novel which has nothing to do with Big Nate and doesn’t even have a title yet, but I’m excited to work on a new project and see where that takes me. I’m always going to keep doing the strip. As long as I’m enjoying the strip and I’m happy with the result and keeping it fresh, I’m going to keep doing the strip as long as I can. The comic strip is what’s what I grew up wanting to do and it’s my first love.

Dueben: You have the same attitude that Charles Schulz and others have which is, your job is to get up and draw every line of every strip every day.

Peirce: Yeah. I have no interest–and never have had any interest–in being a collaborator with someone else on the strip or hiring someone to help me with the strip. Whether that’s just because I’m a total control freak or something else, to me it just seems important that I do the strip without input from someone else.

It’s great to see a long interview like this Again! I didn’t know the timing of the big nate books and the comic strip.

Comments are closed.