AnimEigo is one of the most respected distributors of anime in the United States. Founded by Robert Woodhead and Roe Adams in 1988, they licensed and released classics, including Bubblegum Crisis, Urusei Yatsura, and Megazone 23 in high-quality editions. Until recently, Whitehead has been running the company alongside Natsumi Ueki. However, on February 15, 2024, AnimEigo was acquired by MediaOCD, a video production company best known for its collaborations with distributor Discotek Media.

The Beat contacted Justin Sevakis, founder of MediaOCD and Anime News Network, to discuss AnimEigo’s past, present, and future, as well as that of the anime industry itself.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity of content.

Justin Sevakis Interview

ADAM WESCOTT: What are your first memories of AnimEigo?

JUSTIN SEVAKIS: I think it was Oh My Goddess!, followed by Bubblegum Crisis, AD Police Files, Dagger of Kamui, you name it. The one that made the biggest mark on me was AD Police Files.

WESCOTT: In terms of AD Police Files, did anything about AnimEigo’s release stick out to you?

SEVAKIS: AnimEigo subtitled it themselves. They didn’t outsource it to a caption post-production house like Captions, Inc. They clearly worked more on the translation. Signs were subtitled in an era when that just did not happen. There were liner notes. In the early days, they were printed and came in VHS tape.

It would end with a scroll of all their releases and upcoming release dates. If you were new to anime, it had resources to help you discover more, including the CompuServe anime forum, which couldn’t have been more than 30-40 people at the time. That led to me joining the anime community rather than passively renting tapes.

WESCOTT: Many of AnimEigo’s releases are from the 80s or 90s, like Bubblegum Crisis or Riding Bean. So it’s easy to think of it as a retro brand. But the shows and OVAs they were licensing were contemporary productions, right?

SEVAKIS: Oh My Goddess! came out just a couple of months after Japan. They were fairly contemporary at the time. What cast the company in amber is the DVD crash of 06-’07. They laid off all their staff. From that point on, it became Robert and Natsumi. It wasn’t a company that they were looking to grow significantly again.

WESCOTT: And it’s been that way since then.

SEVAKIS: They’ve been having success with their Kickstarters, and they’ve been putting everything they’ve got into those. Have you seen those Kickstarter releases? They’re incredible.

He did it right out of the gate

WESCOTT: How would you say AnimEigo’s early technological innovations and releases shaped present and future anime distribution?

SEVAKIS: Robert was the programmer of Wizardry and a dyed-in-the-wool tech nerd. The early AnimEigo logo that I repurposed was programmed in 68000 assembly language on a Macintosh 2. Back in the ’80s, adding timed captions to film was hard. You had to have very expensive, esoteric, purpose-built equipment for that. But in 1988, the first video overlay card came out for Macintosh.

The story goes that he and his partner in Wizardry IV, Roe Adams, got their hands on it and played with it. Roe said, “Man, I could buy LaserDiscs and add subtitles for my anime club.” Robert had just done licensing deals in Japan and knew his way around the Japanese industry. He said, “Or, I could license the rights to something and do it right. And we could sell VHS tapes legally.”

Robert wrote his proprietary software in a bubble. He didn’t pay attention to the limitations and standards of captioning in the video world, which is why you see multiple font sizes and multiple colors being used. That was really difficult to do with the professional stuff back then, but he did it right out of the gate.

Today’s subtitle standards are taking the ball and running with it. You see it in fan-oriented releases, like what we do with Discotek. You see it in fansubs, where you have very elaborate typesetting. That is what fans want, and it’s very seldom what the industry will do. Netflix—actually, none of the streaming services—can support multiple fonts or more than two lines of text on the screen at once.

One of the good guys

WESCOTT: When did you first meet Robert Woodhead?

SEVAKIS: I must have met him at a convention while working at Central Park Media in my early 20s. He’s a quiet guy, and he doesn’t socialize at conventions that much. At the time, he did everything in-house, so there was really no need for me to help them out. But I worked for John O’Donnell at Central Park Media, and he referred to Robert Woodhead as one of the good guys. John didn’t like very many people.

WESCOTT: Oh, interesting.

SEVAKIS: They accidentally licensed the same film from two different licensors who weren’t communicating with each other properly. It was the second Urusei Yatsura movie, Beautiful Dreamer. Because Robert had already licensed the rest of Urusei Yatsura, they decided that for continuity, they would just work together. CPM would release it, but AnimEigo would do all the production and ensure everything matched their Urusei Yatsura releases. You ended up with a pretty good release that pleased everybody. That level of cooperation is rare in the US side of the anime business.

WESCOTT: How has anime distribution changed since then?

SEVAKIS: One observation I’ve had while working with Discotek is that they have licensed these touchstones from the past: Berserk, Project A-ko, Memories, and Gunbuster. These are huge moments that people remember and they’re stored in sense memory. Those connections have to be built, they don’t just exist.

Back in the VHS era, it was easy to do that because everyone was releasing two or three tapes a month at most. You had magazine ads that were a giant splash of one show. You had standees at retail that were one or two shows. That doesn’t exist anymore. The most you can hope to get is a tile on whatever streaming service you’re watching.

I think our current era is, as far as pop culture, very overwhelming. A little focus starting at the distributor level is probably good for all of us.

A bunch of absolute weirdos

WESCOTT: The work that you’ve done with Discotek is separate from your work at AnimEigo, correct?

SEVAKIS: Discotek is its own company, but it’s run by one guy, and he’s in Florida, and I’m in LA. My staff and I, MediaOCD, take care of the bulk of their production work. I have a great deal of ownership and pride in the work we’ve done, but it’s not mine exactly.

Very few publishers would allow a team like mine that much freedom. Because we’re a bunch of absolute weirdos, we have taken that freedom and made more work for ourselves. By doing so and by hitting most of our deadlines, we’ve raised the bar of what we’re capable of and what anime Blu-rays could be. I think that got Robert Woodhead’s attention and made him think, “Hey, he’s one of us.”

WESCOTT: In the statement that you made regarding the acquisition of AnimEigo, you said that “fans will turn out to support a presentation made with love and passion.”

SEVAKIS: Back in the halcyon days of Funimation, the people that they had in brand manager positions were enormous weebs who cared about those shows. They were constantly pushing both Japan and other departments in Funimation to work harder, spend a little more money, and make it special.

That’s something I don’t think exists anymore. You can’t put a face on either of the big companies that release anime these days. But you can with Discotek, because it’s us. I think that it’s important both to personalize it and to show that you really went the extra mile. Have you seen our Project A-ko BluRay?

WESCOTT: I have not had a chance to see it. I did see the Discotek Day where they announced they’d found the original print. That was incredible.

SEVAKIS: One of the best days of my life. But…if you see that BluRay, you can tell we lost our minds. We made a full new 30 minute documentary about the Americans that made the music for Project A-ko. We found the old PC-88 Project A-ko game. I think there’s something like eight art galleries.

We spent months restoring that film. That’s not something that other anime labels would do. That is something that the Japan side might do. But they wouldn’t talk about it. Even if you didn’t hear us talk about it, you pop in that disk, and you see everything that’s on there. Almost every review you can find of that BluRay says “this was a labor of love.” That probably did more to sell that disk than any banner at any convention or any free month trial of a streaming service.

You can’t put a price on that

WESCOTT: Did you hear any chatter on the Japan side as well? In terms of folks surprised at the amount of work?

SEVAKIS: We had several Japanese BluRay producers say, “Hey, this is the best one of the best anime Blu-rays ever made.” If you look for the Blu-ray on the Japan side of Amazon, amazon.co.jp, you can see the reviews from Japanese fans going, “Holy crap, why are the Americans doing this?”

WESCOTT: It goes to show: passion on both sides of the ocean.

SEVAKIS: Anime is hard on every level. It’s hard to make, hard to be in the business, and hard to interface with Japan. The only reason we have anime is that a bunch of nerds are passionate about it.

I hope that the stuff that we do makes people’s lives better. It’s almost a dumb thing to say. We’re talking about cartoons; we’re talking about Blu-rays. But I’ll give you an example. When I was seven or eight, this movie was called Defending Your Life. It’s a fun comedy about how, after you die, you go to a special place called Judgment City, where you are put on trial for being afraid. That movie wormed its way into my brain to the point where that is how I live my life. You can’t put a price on that.

When John O’Donnell licensed Project A-ko in 1991, he wasn’t setting out to change lives. He was setting out to make a buck. But Berserk I know has changed lives. When you think about that, it makes sense that people care so much about preserving these shows. I want to do right by those people because I’m one of them.

Running into the fire

WESCOTT: Because you just acquired AnimEigo, you don’t know exactly what the future looks like yet, right?

SEVAKIS: We have to inform Japan and work out agreements with all rights holders so that the AnimEigo contracts are changed to MediaOCD. Then we have to work out how to move all their inventory to our warehouse, which means, “Oh, I need a warehouse.”

Then we can think about what new stuff to license. I have a list of 80 shows that I would love to get. Because we’re still good friends with Discotek, we’re working with them to ensure we’re not going after the same things. I don’t care which of us gets a show as long as someone gets it and preserves it.

WESCOTT: So, are these shows rather than movies or OVAs?

SEVAKIS: It’s some of everything. There’s a lot of stuff on my list that I don’t expect to be acquirable, or if it is, it’ll take a long time. Often, for these older titles, the companies that produce them went out of business, or one of the original creators is dead.

An example I use all the time is Dominion Tank Police, the third anime I ever saw. Discotek has tried to license that repeatedly, but the division of Toshiba that produced it now makes industrial videos. You ask them about anime, and they say, “What are you talking about?” Many of those early 2000s Leiji Matsumoto OVAs are similarly unobtainable because one of the producing companies went under.

WESCOTT: Do you intend to focus on physical distribution? Discotek has licensed its catalog to streaming sites, right?

SEVAKIS: Yeah, and AnimEigo does, too. AnimEigo’s stuff goes to a company called MVD, which then sublicenses to all the digital platforms. If you go to RetroCrush, you can see the entire AnimEigo catalog.

I am going to emphasize the physical end of things. I’m very bullish on Blu-ray. They say in business, you sometimes make more money running into the fire while everyone else is running away.

WESCOTT: So BluRay, not DVD.

SEVAKIS: I don’t have immediate plans to discontinue the current AnimEigo DVDs so long as they sell. But everyone else is sitting on a pile of DVDs they don’t know what to do with. Anime fans have always been more interested in technology. If you’re going to have a show and you’re going to bother buying discs of it, you might as well have it in HD.

It’s going to be a wild year

WESCOTT: Where would you say AnimEigo fits in the anime distribution ecosystem?

SEVAKIS: AnimEigo is a nostalgia brand in its current state. Most of what they’ve been focusing on are shows that were popular in the VHS era. They’ve only been doing major releases via Kickstarter for the last ten years. There are younger fans who have no idea who the hell we are. That’s something I aim to change.

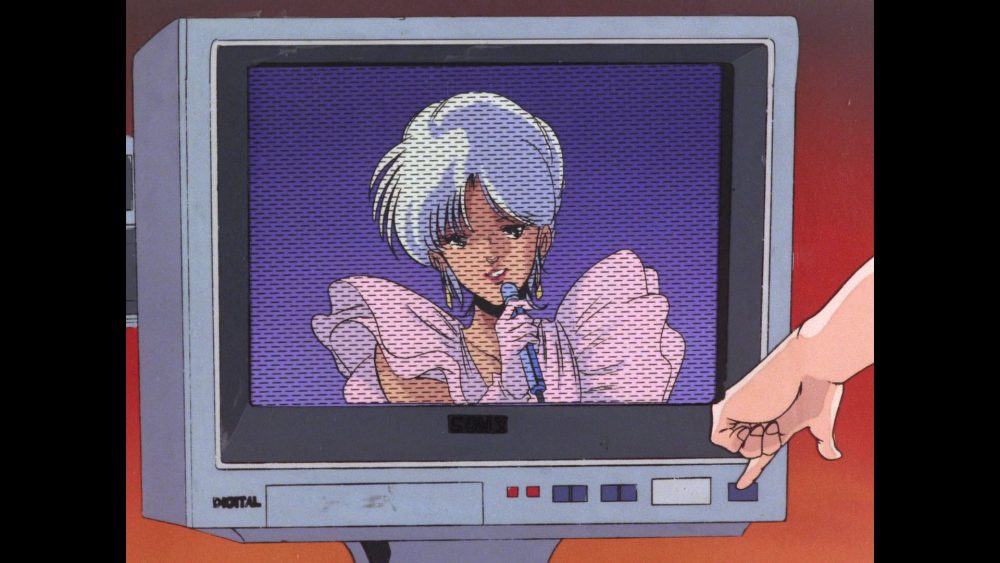

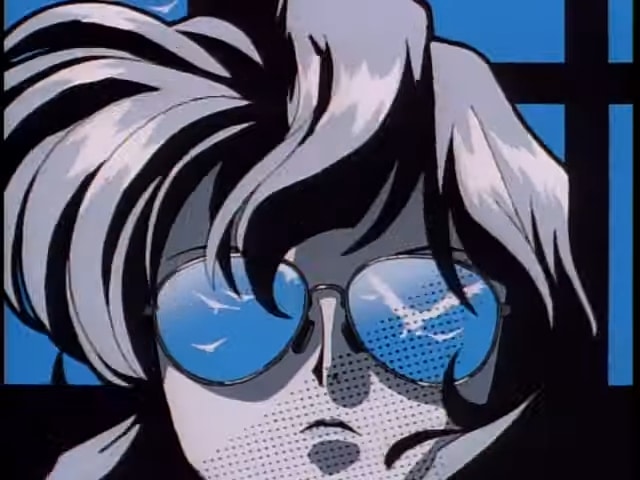

Younger anime fans are really into ’80s anime aesthetics, and I don’t think the industry has done a great job of rising to meet them. Bubblegum Crisis is AnimEigo’s flagship title, and I hope to do a lot with Bubblegum Crisis and its related spin-off works. Beyond that, I think there’s some good merch we could do.

WESCOTT: We also don’t know how long the current state of the anime industry will continue.

SEVAKIS: Now that the bloom is off the streaming rose, I expect to see major repercussions that will hit anime. I’m gravely concerned for any company whose fate is tied in with cable. You see what’s been happening with Viacom and CBS. I don’t think anime will be immune to it.

WESCOTT: Is there anything more you’d like to say? Last words?

SEVAKIS: It’s going to be a wild year. I’m counting on fan support. I hope they look forward to seeing what we’re up to. We’re also open to ideas, so keep talking with us. We’ll keep talking back; hopefully, we can build something cool together.