Interview by Avery Kaplan and Rebecca/Oliver Kaplan.

On Monday, January 23rd, 2023, the award-winning documentary No Straight Lines: The Rise of Queer Comics will be available for streaming through the PBS Video app! Directed by Vivian Kleiman and produced and based on the book by Justin Hall (originally published by Fantagraphics in 2012), the film features Alison Bechdel, Jennifer Camper, Howard Cruse, Rupert Kinnard, Mary Wings, and many additional queer cartoonists.

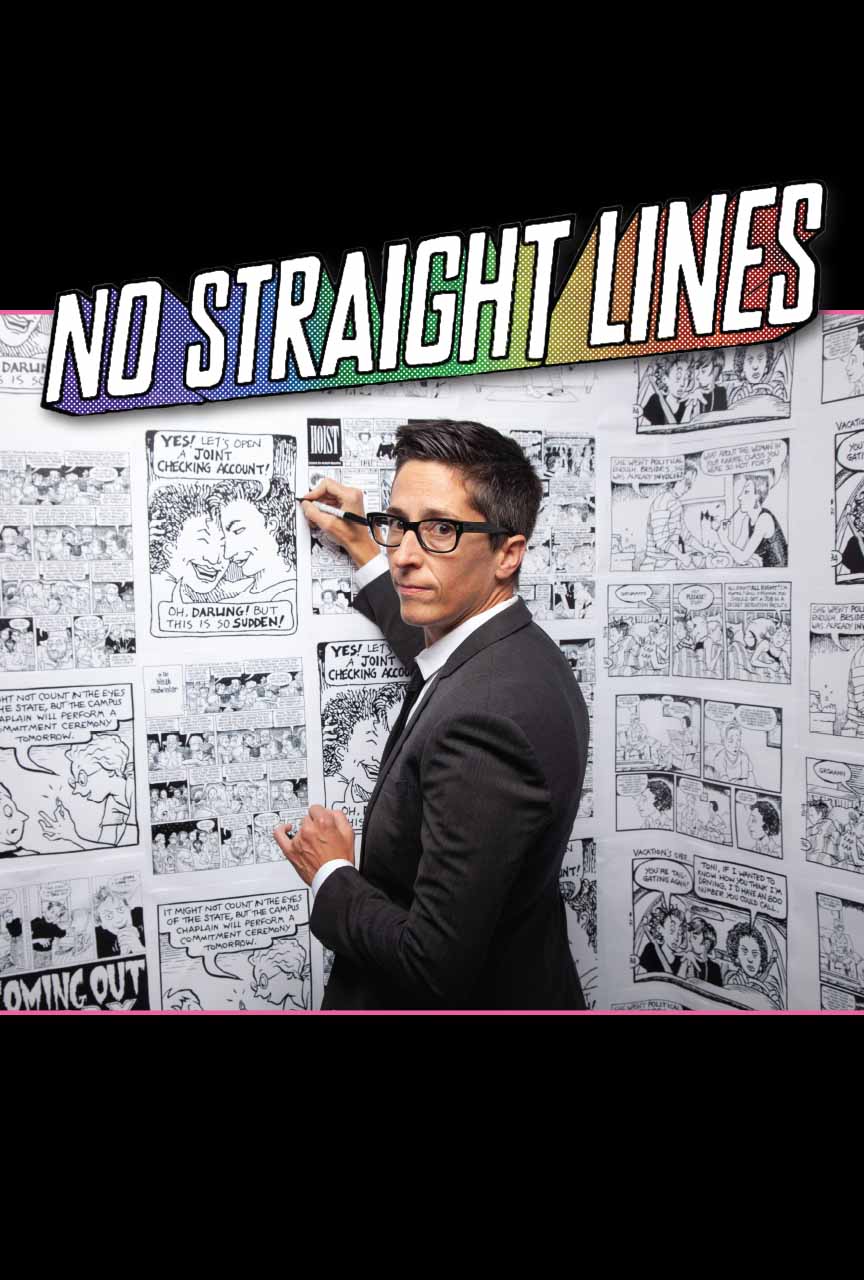

The Beat caught up with Hall over email to learn more about the journey from page to screen, to ask about the evolution of queer comics, and to find out how people have been reacting to this extremely exciting documentary!

AVERY and REBECCA/OLIVER KAPLAN: What was it like seeing your book No Straight Lines serve as the inspiration for this documentary? What has the journey been like?

JUSTIN HALL: I began the movie as I was finishing up the book, actually. A friend Dan Zeitman came up to me in the gym and said, “Hey, why don’t you make a documentary film along with the book?” And I was like, “OK,” having absolutely no idea what that entailed or that it would be a decade-long project! The two of us flailed at it for a couple of years, but we had no idea what we were doing and none of our footage was ultimately usable in the final film. Then my friend Greg Sirota came onboard as Dan pulled back, and Greg (who is an Executive Producer on NSL and a film professional) and I spent a couple of years doing the preliminary interviews and creating a trailer.

Greg moved down to LA and ultimately pulled back from the project himself, and Vivian Kleiman came on as Director/Producer with me continuing on as Producer. We worked on the film for the next six years. Vivian is the real deal as a filmmaker, providing the vision and the skills necessary to complete the movie and get it over the finish line and out into the world.

Fantagraphics and I are working now on a tenth year anniversary edition of the No Straight Lines book, with extra material and a new introduction. It’s funny that it should more-or-less coincide with the debut of the film on PBS! The whole journey has been quite surreal, to say the least.

KAPLANS: How did the queer community utilize comics during and after the AIDs crisis?

HALL: Cartoonists reacted to the AIDS crisis is a number of ways. Some cartoonists created health education comics to do direct good; others raised money through comics anthologies like Strip AIDS. Other cartoonists found it impossible to create work when their lives became a procession of funerals, or they died themselves from the disease.

Many cartoonists, however, did what storytellers from persecuted communities in the midst of crisis do best; they told the truth of their experiences with honesty, rage, and even humor in order to create catharsis for their own community. Even as the majority of American society turned its back on the victims of this horrible disease (remember, Ronald Reagan didn’t even mention the work AIDS until after 10,000 Americans had died of the disease), cartoonists like Jen Camper and Howard Cruse devoted themselves to making the tragedy visible.

KAPLANS: How did you go about choosing and recruiting the creators featured in No Straight Lines?

HALL: It wasn’t an easy decision by any means. But we had some criteria in mind. First off, the film has a tighter focus than the book does. The film is about the pioneers of queer comics, which narrows it to those beginning their careers in the 1970s and 80s. All of the creators in the film are my friends, which is not surprising considering how small the world of queer comics was in the early stages that the film documents, so it was easy to reach out to them.

Historical importance was the first criteria, and all of the creators we profiled broke new ground in some important way: for example, Mary Wings created the first lesbian comic book, Rupert Kinnard created the first Black queer characters in comics, and Camper put together the first queer comics conference.

We also took into account artistic merit and professional accomplishments, which meant that Cruse and Alison Bechdel needed to be included as the two biggest names in the field. Finally, we needed people who were good on camera and had interesting things to say, and all of them fit the bill for that.

We also had a “Greek chorus” of younger queer creators who we interviewed in the film. They commented on the work of the pioneers and provided context. Most of them are former students of mine or faculty from the MFA in Comics program at California College of the Arts.

KAPLANS: Do you have any advice for people who might want to read some of the more rare comics featured in No Straight Lines, like the ‘zines or the out of print books?

HALL: Queer comics haven’t been well archived, but it’s finally starting to happen. Columbia University has the Cruse papers and Smith College has Bechdel’s papers. There are now serious academic researchers doing work on this material, I think in part inspired by the book and now hopefully the film as well, like Margaret Galvan at the University of Florida.

Last Gasp was the publisher and distributor of much of the queer and feminist underground comix movements back in the 70s and 80s, and they still have some of that material in their stocks. And there are punk zine and mini-comics collections that house some of the more obscure queercore material from the 80s and 90s.

KAPLANS: What is the future of queer comics? How is the comics industry as a whole evolving?

HALL: Our film focuses on the time that queer comics existed almost solely in a parallel universe to the rest of comics, namely in the insular media world of LGBTQ+ publishers, distributors, newspapers, magazines, bookstores, etc. Now, that world has largely disappeared as queer material has been allowed into the mainstream (to a certain extent) and the internet has replaced traditional retail spaces.

Instead of actually finding and walking into a gay or feminist bookstore, you can simply Google “queer comics” and come up with long lists of books you can order from the comfort and safety of your home. And of course there are mountains of queer comics being produced on the web now, generating international readerships.

The mainstream American comics industry is also opening up to queer characters, storylines, creators, and fans, as well. You now have folks like Mariko Tamaki or Sina Grace (the latter of whom is in our film) creating independent work for underground queer publications and big book publishers, while at the same time writing queer characters for Marvel or DC. Queer comics were completely marginalized and now they’re becoming centered in the comics world at a surprisingly speed.

Mind you, all of these changes in distribution and publication means that the material being produced changes as well. Hothead Paisan: Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist, a beloved dyke punk mini-comic from the 90s that we profile in the film, is never going to cross over into the mainstream! But now we have very accessible all-ages graphic novels for queer youth. It’s a trade-off.

KAPLANS: Can you speak to the value of knowing queer comics history, both for cartoonists and cultural historians? Why is it important, both inside and outside of our community?

HALL: That’s a great question. Both LGBTQ+ history and comics history are generally undervalued and forgotten histories, the former because it belongs to a community that mainstream society would rather remain invisible and the latter because it belongs to an art form that has rarely been taken seriously. Queer comics history in particular is important because it tells stories of LGBTQ+ lives and experiences through the lens of an uncensored DIY art form made by and for its own community.

Comics are both narrative and visual, which gives the form extra importance for cultural historians interested in how generations of queer communities have seen themselves as well as the world around them. Queer comics often have an authenticity and urgency to them that should be inspiring to all cartoonists.

Until fairly recently, queer identities were usually either erased or labelled as sick and deranged. Mary Wings hadn’t even heard the word lesbian until she was 19; she thought she was the only person like herself in the world. She made Come Out Comix in 1973 to help ensure that no other young woman had to go through that sense of shame and confusion. LGBTQ+ people had to make their own stories to represent themselves in a world that was not willing to do that for them. Queer comics were not just self-expression in the early days; they were survival, and to a certain extent still are. All cartoonists, and all storytellers, can learn from this project.

KAPLANS: What has the reaction to the movie been like so far?

HALL: Phenomenal! Our film debuted at the Tribeca Film Festival, one of the most prestigious possible venues, and then won the Grand Jury Award for Feature Length Documentary at Outfest. It’s been screened in over 100 film festivals around the world and now it’ll debut at PBS, which will bring it before an audience of probably 2-3 million viewers. Honestly, this has been a far greater reaction than we ever expected!

Everywhere we’ve taken the film we’ve been met with such warmth and excitement. We’ve absolutely loved screening it at universities, comics events, libraries, etc. There’s nothing like seeing folks moved and inspired by a project that you’ve spent so much time on. You know then that all of that blood, sweat, and tears was worth it!

Justin Hall is an award-winning cartoonist and educator. He is the creator of the comics True Travel Tales, Hard to Swallow, and Theater of Terror: Revenge of the Queers, and has work in publications such as the Houghton Mifflin Best American Comics, Best Erotic Comics, and the SF Weekly. He created the Lambda-Award-winning and Eisner-nominated collection No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics and was Producer of the feature-length documentary of the same name. Hall is the Chair of the MFA in Comics program at California College of the Arts, the first Fulbright Scholar of comics, has written about comics for various academic publications, and has curated international exhibitions of comics art. He is now at work on a graphic novel that weaves memoir with queer San Francisco history for Abrams Books. Visit his website at justinhallawesomecomics.com to learn more!

Will you be streaming No Straight Lines when it arrives on the PBS Video app on Jan 23rd? The Beat wants to hear from you! Give us a shout-out and let us know, either here in the comment section or over on social media @comicsbeat!

I’ve started watching this on the PBS app but it is censored! Can one only see it uncensored by buying the film? PBS censoring it makes no sense. In the 1970s PBS broadcast the play The Trial of the Chicago 7 which had the F-word used on TV for the first time. They also showed “I, Claudius” uncensored in 1976. But now they censor a film about underground comix?

Comments are closed.