James Albon’s illustration style has a distinct New Yorker quality to it, and that helps in its evocation of another era that you can’t quite put your finger on. Might be 100 years ago, might be 20. Probably European? But where in Europe? It’s this mysterious aspect of his work that offers him the freedom to explore such ideas as the nature of being an artist, how much an artist can control the perception of their art, and the relationship between politics and the artist within a context removed from the drudgery of headlines or even history. Like his art, Albon’s stories take aspects of reality and recasts them in a setting that services a real examination of them rather than through the inevitable gauze of nostalgia.

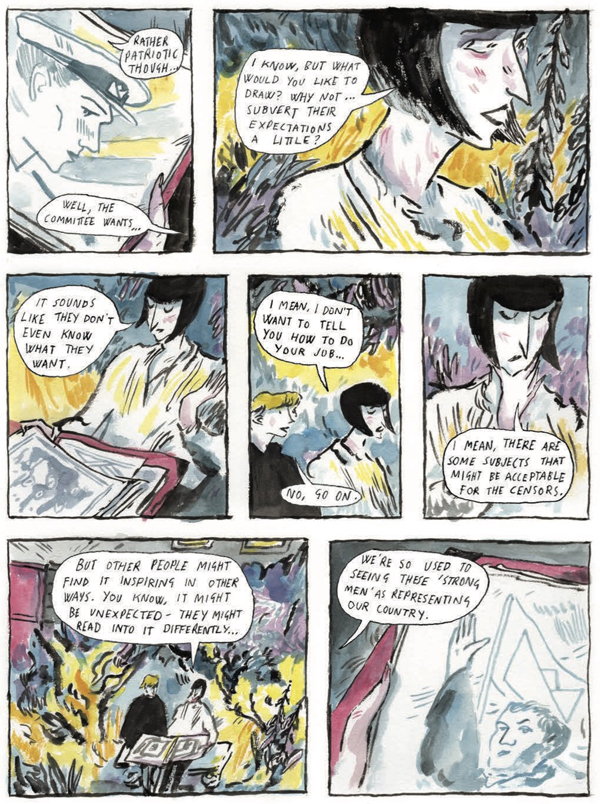

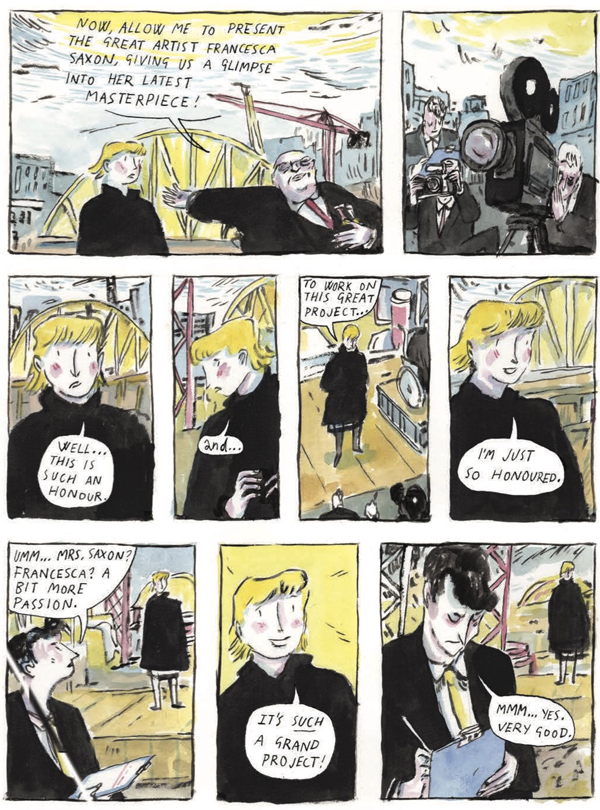

In his new book A Shining Beacon from Top Shelf Productions, a painter in a Soviet-style country is tapped to add patriotic decoration to a new national monument meant to inspire the people in the country, but the more she struggles with what she should paint, the more entwined she becomes with political struggles within the country.

Albon grew up in Scotland and currently lives in Glasgow with his partner Cat O’Neil, though he was born in Cambridge, England. Albon’s work has appeared in the Wall Street Journal and The Guardian, and he’s previously illustrated editions of Of Mice and Men, Parade’s End, and The Blue Flower for The Folio Society.

——–

A Shining Beacon really reaches back to a Soviet form of totalitarianism, but at the same time, it’s incredibly relevant to aspects of the political situation in the United States and the U.K. How intentional was that mix?

When I wrote it, I wanted to be deliberately vague about the exact setting and the exact politics of the different factions within the book. It was a really funny thing because I started writing it at the start of 2016 before Brexit and before Donald Trump when they were on the horizon, but no one thought it was going to happen. I was very influenced by books from places, places like Hungary and the Czech Republic, from the communist period there and these descriptions of European communism.

I wanted to write a book that tackled the same themes, but I think certainly in the U.K., and I imagine in the USA as well, often when we talk about communism we’re like, oh, that’s something that happens to Russians, but it’ll never happen here. So I wanted it to be deliberately vague in terms of its location and see if people could imagine that it would happen in Britain or in America, places where they’re reading it in their own language.

Then obviously in the last three years, we now have Brexit and Donald Trump and a lot of people have read it and said, oh, so it’s set in Britain, right? It’s set in Brexit, Britain. It’s interesting because they’ve projected a political reality onto it, which isn’t explicitly in the book. But I really liked the way they will interpret it in different ways.

Not even five years ago would the kinds of touchstones referencing, say, East Germany or Soviet Russia that you present in the story be recognized as reminiscent of the U.S. or the U.K. That would have been unthinkable.

Yeah, exactly. So, in a way it’s exciting for me that I’ve managed to write a book that has contemporary political relevance, but at the same time I would much rather that we didn’t have Brexit and my book was this quaint niche thing, rather than it being something like, wow, it really speaks to the current political state.

You were ahead of the game, obviously. But you also seem very familiar with the imagery of the Soviet era, and also have an ability to connect the dots even if they weren’t so obvious when you began working on the book.

I think you’re right there. I think especially in terms of my specific influences, the thing that I was sort of really interested in was books like The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera and I Served the King of England by Bohumil Hrabal. Both of those are set in Prague, but often when we think of the USSR, we think of Russia and Moscow and Stalin and these absolute extremes of terrible atrocities. Obviously, there was terrible political repression in European communist states, like in Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia but they didn’t necessarily operate in exactly the same way that communist Russia did. And there’s this specificity of communism in Yugoslavia or Romania or Czechoslovakia that was something that I found very interesting. I very much appreciate that most readers will have like a working knowledge of Stalin’s reign but won’t necessarily know as much about sort of communism in central Europe so it’s not by any means explicitly set in communist central Europe.

But what I really admired was the way that writers from that period wrote about their own cultures with a combination of frustration but also affection. And they used a combination of comedy and tragedy to deal with the political situations in their own countries. So it was reacting to writers like that, that was exciting. They’re very exciting writers to read and as you can imagine, stimulated me to, write in reaction to them, as a jumping off point for writing about something that’s kind of set in Britain but not explicitly set in Britain.

You really capture something about life in one of those countries that has only really come to be understood since the fall of communism, the idea that they were populated by ordinary people living ordinary lives and their complete experience wasn’t a constant 1984ish crushing oppression 24 hours a day. They did manage to have some enjoyment in life despite surveillance and detainments and other authoritarian staples.

I think it’s really interesting balance and again, this is why while I’m influenced by writers from Communist central Europe, I wouldn’t want to explicitly write a book set there because I don’t feel like I know enough first hand to take the voice of people who have had these experiences. But it’s always been interesting to me.

The way I got interested in the histories of countries like Hungary and the Czech Republic is that when I was an art student, I did an Erasmus exchange in France. And when I was studying in France, I made and I’m still very close friends with a couple of people from Budapest, and then a couple of people from Prague as well, and someone from Estonia. What was really interesting was that, especially as a student, it was around the time of the film The Lives of Others by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck. That film came out and you either hear about the absolute terror under communism, which obviously was a very horrifying reality for people.

Or you hear about a kind of sophomoric student infatuation with communism where are people like, ‘Che Guevara was so handsome’ or ‘Lenin had such great mustache’ or ‘wouldn’t we all be better if we lived under communism.’ It’s wonderful that there are a lot of students who want to improve social conditions in their own countries, but obviously, full communism isn’t the way to do it. But what was interesting was visiting friends in Prague or in Budapest and talking to them and talking to like their parents and people of their parents’ generation about the communist period. What was interesting is that their lives weren’t as extreme as to reflect The Lives of Others.

I think people either living under communism or living under capitalism just want to have a house and a family. And a job and social life. Everyone fundamentally has the same sort of human needs, so I really wanted to put that into the book. The idea that it’s not a simple case of, people opposing the government in an extremist way or marching in lockstep with the government, but actually most people wanting to have regular lives and wanting to have comfort and wanting to just have security in this society. And most of the time if people are put under pressure, they don’t exclusively start marching in the streets and try to overthrow the state. They actually retract and they try to conserve the security that they already have.

And so for me, from a writing perspective, it had this really interesting effect of all the characters, but especially on the character of Redford who is the warden, the law enforcement officer in the story who has, despite his family having been oppressed by the state, joined the police because it seems like a career that will give him stability. He hopes that he’ll be able to make something of himself through that path, even though it’s a path that is part of the same mechanism that suppressed his family in the first place.

And what you’re describing can apply to citizens in all sorts of political situations in countries that feature ordinary people just trying to carve out a life for themselves despite their government, but also sometimes having to utilize or at least tolerate aspects of the government they oppose just to have opportunities.

I think it’s something that everyone can empathize whether or not you live in a totalitarian state. The kinds of the structures that shape our society are things that, as the man on the street, you can use for security and support but can also be used by the state or by a corporation to oppress you. Overall the thing I wanted to say with the book was that our relationships with our countries and our political structures — and taking it as a metaphor for a reflection on capitalism, the commercial structures that we live in as well — these are things that can be positive or negative, but the way that we interact with them as people are nuanced.

Basically, the other sort of jumping off point I had for writing the book is it’s actually really a reaction against V for Vendetta, the classic Alan Moore comic. Essentially the gist of that comic is that, if the government’s bad then everyone will be inspired to rise up and overthrow them, which is obviously like fundamentally a point that we should all be able to agree with because it’s really heartening to see that people as a whole have a strong sense of morality and righteousness and can act together to improve their lives. But in practice, it’s a book that kind of says, f you don’t like your government, you can violently overthrow them. And if you violently destroy civic institutions, they will just be rebuilt. And there’s always this phrase that I find quite funny, which is ‘everyone wants a revolution but nobody wants to do the dishes.’

I think V for Vendetta is a book that suggests that if you can violently overthrow the state, we’ll just miraculously be fine afterwards, whereas what I wanted to say in this book — because obviously, the plot line deals with revolutionaries and people who want to overthrow the state and a question over what they’ll do next — was that it’s always worth saying it’s wonderful to aspire to improve everyone’s wellbeing in society, but there has to be a positive structure in how that’s going to be done. If you smash it, civic institutions you are just left with nothing. So that was another side of the motivation behind writing the book, writing the book, this idea that people could live ordinary lives and don’t necessarily wake up in the morning and overthrow the government and then everything’s fine the next day.

The other component your book is, of course, the portrayal of the use of art in these political situations, the idea that art can be construed as political even if it’s not meant that way.

For me working as an artist myself, that’s the most interesting part of the book, the relationship between politics and art. And there were loads of different things that provoked me into thinking about this and wanting to write about this. On the one hand, I think that as a society ourselves, like in Britain or the USA, we have an interesting relationship with our visual culture and creative culture in general. Obviously this is all the kind of stuff that people write entire dissertations on and I’m skimming over the surface of it, but like the relationship between when people talk about what art is good and what artists are good and appropriate, it’s quite often subsumed by a political idea of what seems good or worthwhile as opposed to looking at these internal components of the art itself or the way that the art fulfills its own form and content. Often we glance over the form and content and we go straight to talking about the political meaning of the way the arts interacts with its context and it can be often only judged on that, which is obviously a relevant part about it, but it’s not the only way to look at it. There’s also this really interesting thing I was reading about the relationship between writing and politics. So writing as an art in politics in The Russian Journal by John Steinbeck.

In 1946, he goes to travel around Russia as it’s rebuilding from the war and has a wonderful time there and really wants to say that Russian people in American people have no reason to hate each other because we all fundamentally are humans and want to support each other. We all want the same things. He’s obviously writing this before the world about Stalin committing genocide, but the message is something that I very much agree with. Even though they are countries on the opposite side of the world, he’s discovering that Russian people, want to have a home and family and security in much the same way that Americans do.

But there’s an interesting thing where Stalin says that writers are the architects of the soul and Stalin loves writers and loves the arts in general. And — again going off on a tangent — he had a very interesting and complicated relationship with Mikhail Bulgakov, the novelist and playwright, which was again something I looked at when writing the book. But the conclusion that Steinbeck comes to is that it’s complicated comparing Russian authors and American authors — because Russian authors are celebrated by the communist state because they’re an architect of the soul in inverted commas, because they’re writing what the state wants them to write and they’re writing these politically aspirational things, whereas writers are mostly despised in the USA. Steinbeck says they’re mostly despised in the USA because they’re saying all the uncomfortable truths that the state and that the government doesn’t want to hear.

That was for me a really interesting jumping off point for the character of Francesca, the main character. She’s chosen to paint this propaganda mural for the state not because she’s an especially talented artist or because she’s a big celebrity or anything, but because as a young woman from the countryside, she’s just seen as somebody who will make all the right things and they can just push her around and get her to toe the party line, and that she will fall into that “architect for the soul/agent of the state” role more easily than a more outgoing, famous artist would.

You also address the concept of seemingly benign imagery that we’re all used to see that functions as unobtrusive propaganda for nationalism. And interestingly, the artist character in your story is neither really aligned with the state or the opposition to the state. She’s a bit apolitical, but that proves to be a hard thing to maintain.

Yeah, absolutely. I think that the thing that’s interesting in her plotline is that the whole way through she’s trying to develop these compositions of what she thinks the government will like and they keep finding problems because the government itself is this sort of convoluted bureaucracy where different committees are constantly infighting and constantly contradicting one another as part of their own internal power plays. Things that are ostensibly really, really overtly patriotic get shot down for nonsense reasons and throughout the story, she gets caught between two different ideologies, a pro-government and a revolutionary group who have very different ideas of what she should draw.

And in the end, she’s so much between a rock and a hard place that she realizes that the best solution isn’t to make art, as I was saying earlier, that is solely judged by its relationship to its political context, but to make art in which a form and function and content marry one another and make art that is just good in and of itself without attaching itself to either side of the political context. So she creates this mural and, and despite everything previously having been shot down by these sensitive committees, everyone loves it, but the two factions both look at it and project their own political views onto it. So both factions look at it and love it, but one wants to say, “oh yes, it’s a perfect metaphor for the strength of our government” and the other faction says, “oh, it’s a perfect metaphor for the righteousness of the revolution.” So it’s meant to be an unfortunate irony that even when she tries to do something for the sake of beauty and for the sake of art and communication, even though she achieves what she set out to do, it still gets co-opted by a malign, political influence.

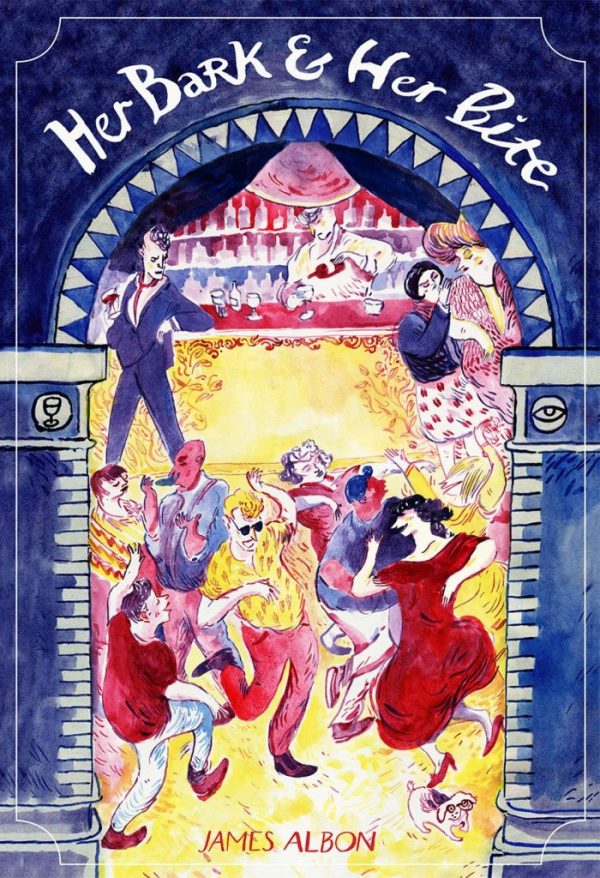

I had read and reviewed Her Bark and Her Bite a couple of years ago, and I was thinking that it portrays the opposite situation of creating art where it’s almost like a free for all. The characters have complete freedom to create and figure out what to do and how to do it, but that proves to be creatively limiting in its own way.

Her Bark and Her Bite is a funny one to compare because it’s a very, very different kind of story to A Shining Beacon, though they’re both about young female artists from the countryside coming to the big city and being unprepared for what awaits them there. In Her Bark and Her Bite, as you say, they’re free to do whatever they like in their art. And generally, all the characters, are libertines, basically, all the characters are just free to party and free to have the lifestyle that they want. But with Rebecca, the main character of Her Bark and Her Bite, the struggle is more internal. It’s the temptation of, which I’m sure every artist and every writer in the world feels, should I spend a few more hours in the studio and finish this bit of work or should I go to the bar and just go and party, you know? So she’s under a different sort of social pressure, but it’s still about the battle of one’s own relationship with one’s creativity versus the wider context that one is creating in, which is a question that really, really interests me. Although I have now started writing my third book and I promise this time it won’t be about an artist. I don’t want to become one of those artists who only writes about other artists.

Her Bark and Her Bite and A Shining Beacon do share a lot visually, especially regarding their portrayal of no particular era. They both have a retro quality to them, but without evoking a specific time or place.

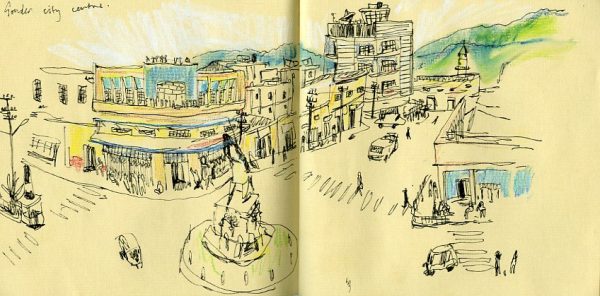

Yeah, I think so. Well, it’s interesting, the way that I create these spaces is I draw a lot in a sketchbook, so whenever I’m going around and traveling, I’ll take a sketchbook with me and just sketch — sketch in the airport, sketch in bars, sketch in cafes. Both the worlds of A Shining Beacon and of Her Bark and Her Bite were very, very based on sketchbook drawings. For Her Bark and Her Bite I was living in London. When I was working on A Shining Beacon, I was living in Lille, in France. Between those two places— my wife is half Hong Kong Chinese, she’s an illustrator as well, and we’d gone off to live in Hong Kong for a year.

So there was a big influence of Hong Kong, the madness of Hong Kong’s, especially central Hong Kong’s, architecture where you have a combination of traditional Chinese aspects like temples and a lot of Chinese typography everywhere with these enormous skyscrapers and things. So I think the colorfulness of Hong Kong also fed a lot into the look of Her Bark and Her Bite and it’s also just influenced by a lot of sketchbook drawings from wherever I’ve been on holiday, so there are bits of Italy and bits of France in there as well. I think for me, having a strong grounding in observational drawing and reality means that you can create a fictional city that still feels like a real city even though it’s unchained to a specific place or a specific time.

And I might even go so far as to say that in both books the locations are characters unto themselves. They’re very fully realized and a crucial part of the story.

Yeah, absolutely. I’m sure any comic artist will tell you that one of the great pleasures of writing a graphic novel is building the world. You know, it’s inventing the city and inventing the look and feel of a place. There are pages and pages of notes of the political structures and the national structures of A Shining Beacon that never appear in the book. But it’s just, it’s a real pleasure to create a city so vividly and comprehensively. Funnily enough, my next book is going to be set in London, in the real world, in the present day. So it’ll be interesting to see how much it maintains itself as real contemporary London and how much it becomes a fictionalized pseudo-London.

With A Shining Beacon, it was very important for me as well to not set it in the present day. It’s almost sort of a visual and practical decision but one of the important elements of the story actually is the espionage element. The fact that she’s being watched all the time and she’s being followed or she goes to meet these revolutionaries and she’s not sure if she’s being followed. I think it’s something that one sees a lot, especially in movies nowadays where if the story was specifically set in the present day, obviously all the monitoring would be done by computer. But it’s difficult to show espionage and drama happening with computers in a way that is interesting, unfortunately.

Take films like The Social Network by David Fincher — he’s a wonderful director, but he’s forced to show people just typing on computers with like exciting music in the background and it’s really visually not very stimulating. The notion of someone physically being followed by a mysterious character in a trench coat is much more interesting than here’s some people on a computer typing over to the character being followed. So it’s really deliberately not in the present day.

Is your next book political?

It’s not so political. I guess it’ll fit between A Shining Beacon and Her Bark and Her Bite, It’s not specifically political, but it’s going to be about a restaurant in London. The script is approaching completion. The visuals are beginning to begin. Hopefully, it will combine comedy and drama and it will combine the moral torpor of a really good drama with the exciting fine dining, high lifestyle culture, and visuals that are really fun to draw and create characters that are really fun to interact with. It took me just over two years to finish A Shining Beacon, so we’ll see how far I’ll be in two years. I’ll be talking to you again with hopefully an extremely exciting new book sitting on my lap.

Terrific points and discussion here. Could stand to read stuff like this, anytime

Comments are closed.