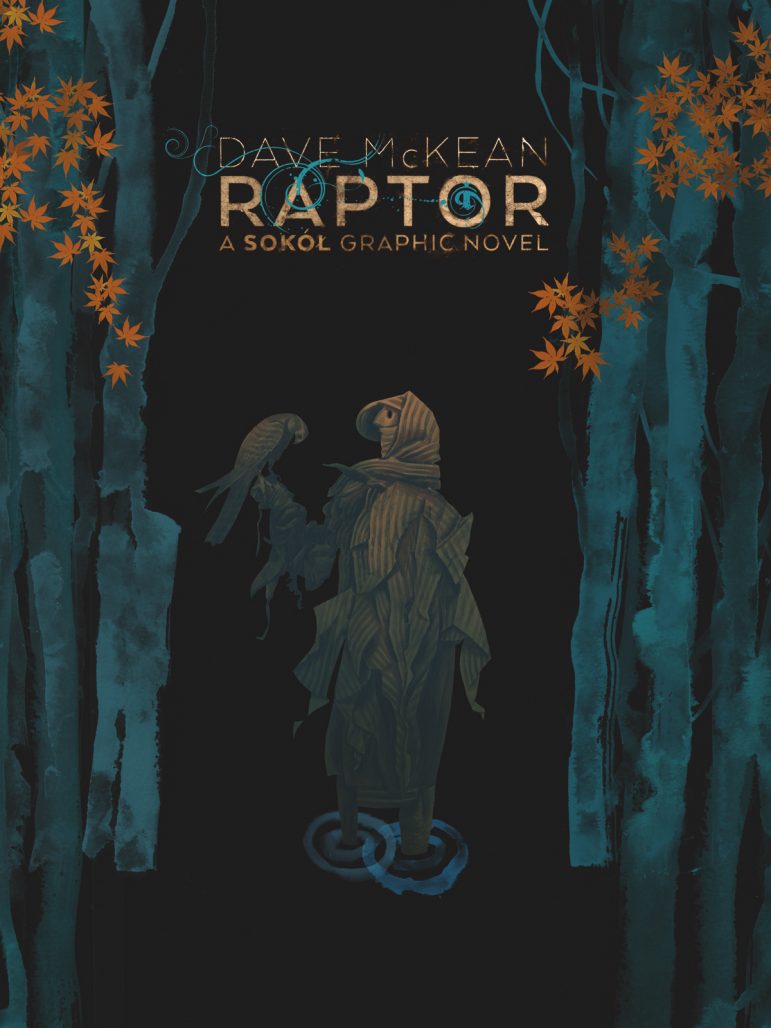

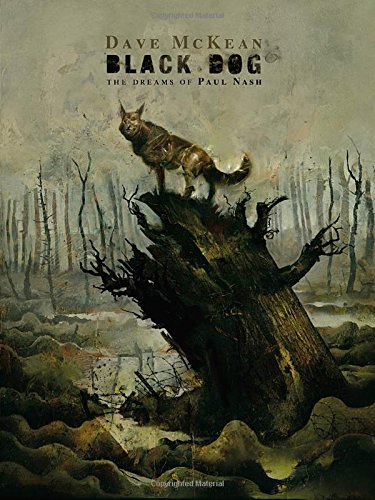

It has been a little while since we last saw the work of writer/artist/everythingist Dave McKean grace the comics page. His last published work was 2016’s Black Dog: The Dreams of Paul Nash, an exploration of the early twentieth century surrealist painter and war artist as part of the 14-18 Now Foundation‘s World War One centenary commemorations. Five years on, Mr. McKean is returning with Raptor: A Sokol Graphic Novel.

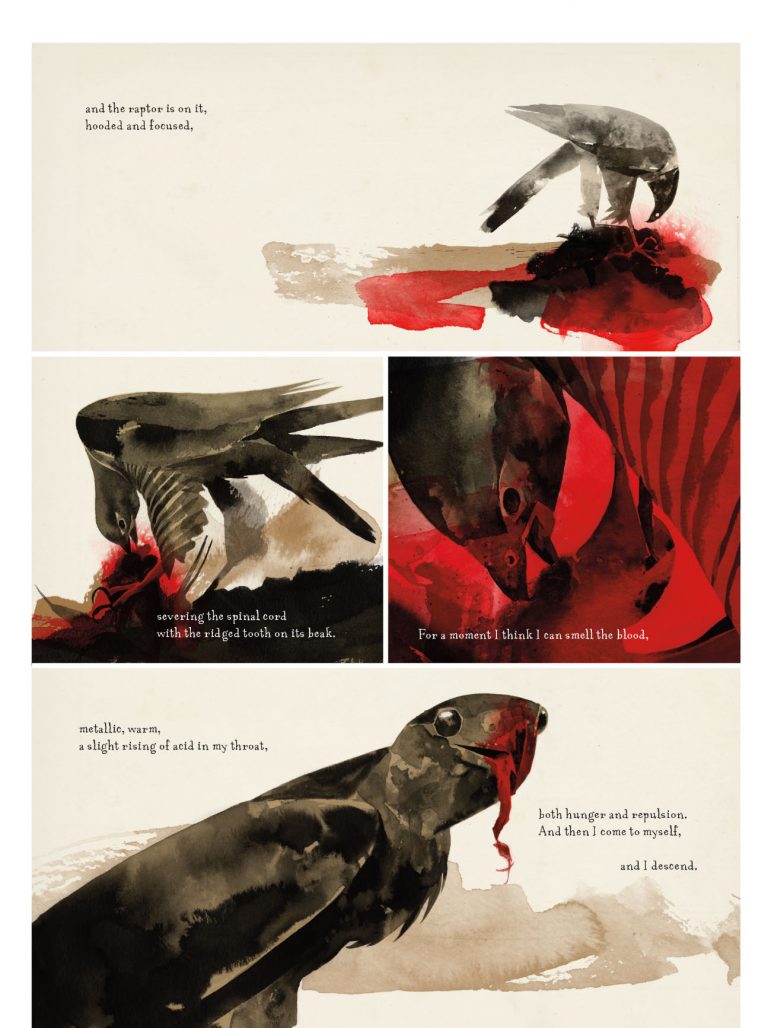

In Raptor we meet two personages across parallel narratives: the bleak fantasy landscape where the mercenary Sokol makes his life and living; and Arthur, a troubled, grieving author in 19th century Wales. Interestingly, Raptor has been described by publisher Dark Horse Comics as “his first creator-owned character”, which is surprising for an artist that has been involved in the comics industry for over thirty years.

While Raptor may be a few months away from its July release, The Beat‘s humble gopher Dean Simons had the opportunity to ask the versatile auteur about his latest book and the process in bringing it from idea to visual life.

DEAN SIMONS: As a multidisciplinary artist and filmmaker, what keeps attracting you to the comics/sequential art medium?

DAVE MCKEAN: Comics were my first love and remain the place where I most feel at home and in control of the projects I want to do. I don’t need a budget, or a cast, or permission from anyone else to start working, I can think of an idea and control it from the first line to publication day. Comics make good use of my strengths, as a draughtsman and storyteller. As time passes I appreciate more and more the freedom I have making the comics I want to make, and though I’ve enjoyed other media, and found wonderful highs in moments making films and exhibitions and theatre, I haven’t found outside of comics that constant daily pleasure of developing an idea on the page and seeing the book develop.

SIMONS: Where did the concept, setting and characters for Raptor come from? How long had they been gestating? What made you commit to this graphic novel over other ideas?

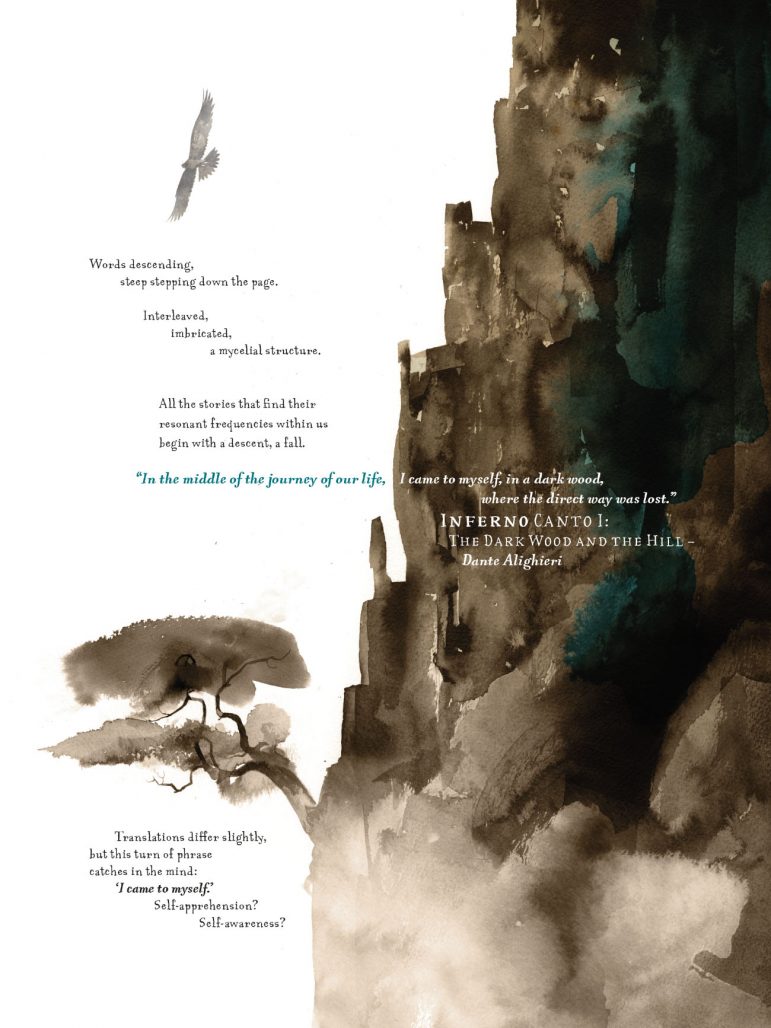

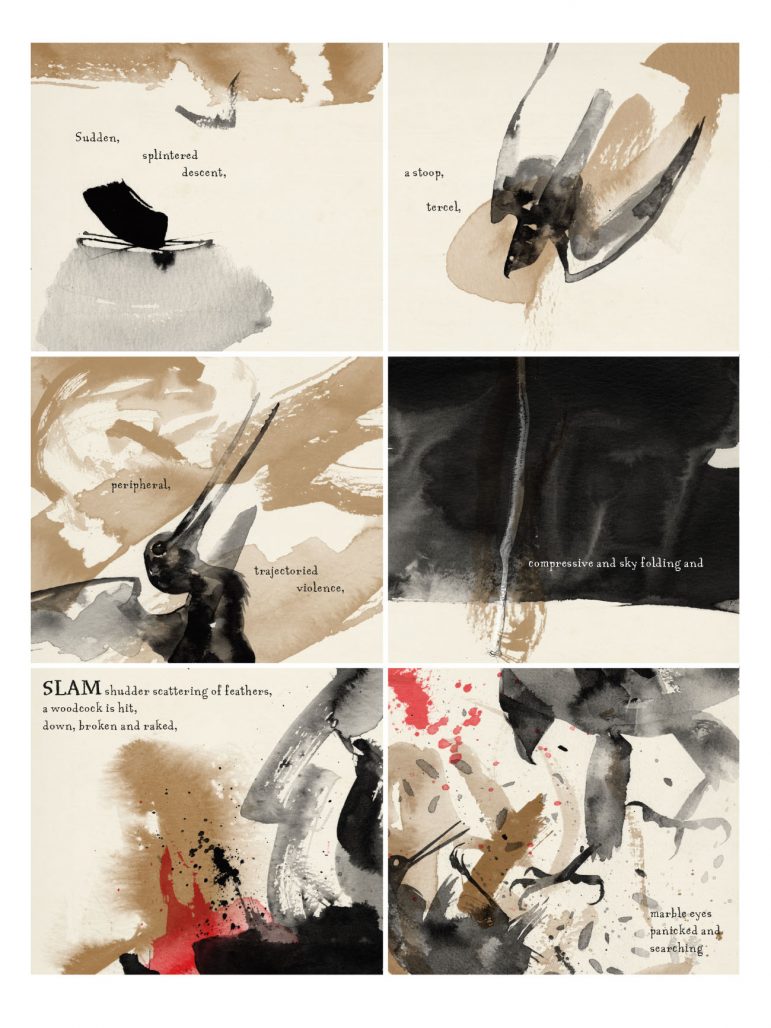

MCKEAN: It had a circuitous beginning. I was asked to do a short story for an established character, I thought immediately of a longer story, but though it was suitable, actually it was too personal an idea to hand over to someone else’s world, so I spent a frantic week reworking it, developing my own lead character, and placing it in a world that I felt much more at home with. I wanted to do something that was inspired by the contemporary nature and travel literature I’ve been reading, something that would express my love of the natural world, and something that would live in this realm between reality and the imagination. My character is trapped between those two worlds, the state of human and bird, or reality and fantasy, of civilised life and raw animal instinct. I have several other GN projects in pieces in my notebooks, whichever one crystalizes into a solid story and script first ends up being the next one on my drawing board.

SIMONS: Did you have any apprehensions about the book? Do you still experience any when confronted by the blank page or canvas (or even letting go when it is done)?

MCKEAN: Not so much with the drawing, although every new project takes a while to get into the ‘flow’- that state where I’m not overthinking or worrying it, and not under-thinking or bored by it. This book ended up wasting a lot of paper in the beginning, as I threw out initial versions of scenes, and redrew them. The writing still fills me with apprehension, now more than ever. To write something, you have to commit to the ideas in the book, and the world is so fractious at the moment, and the level of debate so toxic, it needs a degree of bravado, determination, and a stiff drink or two to enter into the fray.

SIMONS: Did you approach Raptor differently to your previous graphic novel, Black Dog?

MCKEAN: In some ways, no – I’ve inherited Bill Mitchell’s working methods from my time with the Wildworks Theatre Company, and I’ve tried to apply his improvisational, exploratory way of developing ideas to everything I’m working on at the moment. But in other ways, yes – Raptor is more of a traditional linear narrative, whereas Black Dog was a series of moments, or dreams, that sketched in an idea of Paul Nash’s life and inner life.

SIMONS: Raptor follows two narratives and raises the idea of a two-way relationship between author and audience, dream and dreamer – was this prominent in your mind as you worked on the book?

MCKEAN: Yes. I like this conversation across the line of creator and creation, artwork and audience. I think it’s a world and character with which I could explore many ideas. I wanted to plant a few seeds of who he is, what he is, where he’s come from and where he’s going, but leave a lot unsaid so I can maybe fill in pieces of the puzzle in future stories.

SIMONS: You have the ‘A Sokol Graphic Novel’ subtitle on the book. Are there already more stories in the works involving the mysterious Sokol and the seemingly lost Arthur?

MCKEAN: Probably not Arthur – I feel he reached some equanimity in his grief and relationship to the real world. If you think of the Raptor character as a source of inspiration from that other realm, I think he might well interact with other people from our world, from other times and places as he travels across his land. It’s a very open-ended place to explore. I like the idea of a futuristic virtual story, or possibly something touching the origins of human communication…

SIMONS: Sokol has been described as your first “creator-owned character”, was that the main impetus for the book? Why now?

MCKEAN: Well, he is my first character that could plausibly be continued into further stories. I tend to write self-contained stories. The main impetus was simply to tell this story, explore this idea more fully, an idea I’ve touched on before in my book Cages and in my films MirrorMask and Luna, and to begin something that I can return to and expand and explore. Why now? I think there are pressures at play in current cultural conversations that threaten the individual’s ability to create and imagine freely. Responsibly, of course, sensitively, of course, but not without the freedom to go anywhere and explore any idea. “To play lightly with ideas” as Oscar Wilde put it.

SIMONS: I noticed in the backmatter that there was a picture of you trying your hand at falconry. Is this a new hobby or was it a part of your research for Sokol? What other curious things have you done in the name of research for this book (and others)?

MCKEAN: It was research, and a wonderful birthday present from my daughter. I love researching and entering into new worlds for new projects. I’ve been taught how to hunt as a wolf for Wolf’s Child by an ex-marine who left the human race for a year to live with a pack. I’ve spent time in the madness and balletic choreography of Michelin starred kitchens for my work with Heston Blumenthal. I’ve gone back to school (actually my kids’ school) to retake the lessons in physics and chemistry I didn’t pay attention to when I was in my teens, in order to get my head around chapters of my book with Richard Dawkins – a wonderful experience, and proof to me that no-one should go to school until they’re at least thirty, you really appreciate it then.

SIMONS: I was wondering about your working, planning and plotting techniques – what is your starting point? (for instance do you tend to start from a sketched image in your notebook, a snatch of dialogue or description, etc?)

MCKEAN: Stories begin in fragments, images, scenes, moments, snatches of dialogue. But they become more plausible as potential projects once I have a strong ending (the hardest part of the script), a good beginning (the easiest), an event in the middle that dog-legs the story, a sense of the sound of it, the music of it, even if it will eventually be a book with no sound, and some sense of what it’s about at its core, and why I’ll be spending a year or so of my life on it – and why that’s important, if only to me.

SIMONS: Are you a meticulous planner or do you generally prefer to work organically? Has this emerged over time or is it an old habit that has served you well since art school?

MCKEAN: I used to be a meticulous planner, but I’ve gradually embraced the pleasure and fear of being out of control. It’s something that is hard to do at the beginning of your creative career. You need to have had some projects work, and to notice how being alive to change and improvisation improves the work, and to see that these things usually do work out in the end, for you to fully let go. Again, I owe this lesson to Bill Mitchell.

SIMONS: How much of Raptor was produced digitally and how much on physical canvas, paints and inks? Do you have a preference?

MCKEAN: All of it was drawn in ink and pencil, with a few painted pages. Then it is all scanned and shaped digitally. Sometimes there is quite a lot of digital work, sometimes almost nothing beyond a clean up for print, but hopefully nothing strays too far from the handmade quality and energy of real media.

SIMONS: From a reader’s perspective, I notice that the pacing blurs somewhat with that of illustrated stories (rather than the more rapid pacing of the average comic) – Is that a specific style you try to emulate and maintain when it comes to how you wish or expect the reader to approach your work?

MCKEAN: It depends on the nature of the scene. Some of the scenes as Sokol is walking, but with narrative captions that are actually from Arthur’s story reflecting on what we’re seeing of Raptor’s world, have an illustrated story feeling to them, but this parallel narrative approach is, as far as I’m concerned, pure comics. I think most of Raptor is quite traditional comic book storytelling. Black Dog was more on the edge of being a profusely illustrated narrative – that was the nature of the beast.

As for rapid pacing? I don’t think the speed of the narrative has anything to do with defining the nature of comics. They can be as slow as Béla Tarr.

SIMONS: Back in 2018, there was a furore about a book that you were working on for Abrams. The book was cancelled, and you had a back and forth with another comics journalist online. How much of the book was finished when it was scrapped? Also, now three years on, what are your thoughts about it? Has it changed how you approach projects? Has it jaded you?

MCKEAN: I supported the pausing of the book at the time mostly because I wanted to do it with Amnesty International, and when they withdrew I also lost faith in it. I’ve just been writing about this episode for the retrospective book I’m working on at the moment, so I’ll try and address this there. Yes it has changed my approach to projects, but no it hasn’t jaded me.

SIMONS: How do you view comics today compared to when you were a reader and when you first entered as a professional artist?

MCKEAN: I think it’s a golden age for comics at the moment. So many more books published and many more publishers including book publishers with GN lists. Many more voices, often without the baggage of nostalgia dragging them into cliché. But on the downside, the move from an analog world to a digital world and the wreckage of the high street [physical retail] has made it much tougher to be seen, and to make a living making comics. The sheer quantity of books fighting for shelf space makes it harder again, but you just have to rise to the challenge. Online is okay, but I still love physical books in a physical world.

I always hoped for a world where comics were considered to be just another art form, unique in its properties, like film or theatre or the novel. I think we’ve come considerably closer to that view.

SIMONS: How has the pandemic specifically affected your work? Has much changed?

MCKEAN: No. I have been very lucky. I live in the country and lead a fairly self-isolated life anyway. I had planned a year off travelling, getting a series of books and projects finished or further along, without interruption. This year, with the world taking a breath, has been a year of concentrated work and reflection. Working out what really matters to me, and what my little place in the world means. I’ve walked every morning, photographed the birdlife, got to know my part of the country much more closely. My studio is now clear and works.

There is much about this year I will miss as the rapaciously consumerist world begins to start up again. I have friends who have had a much tougher time than me, and I empathise with their difficulties, and in some cases, dreadful losses, and can appreciate the desire to see friends and share experiences again. In some way though, I considered this strange year a kind of heart murmur for the world. One of those little shocks that makes you think, “I really need to look after myself a bit better”. Will we learn that lesson?

Raptor: A Sokol Graphic Novel will arrive from Dark Horse Comics in all nifty comic shops July 7 and bookstores July 20.