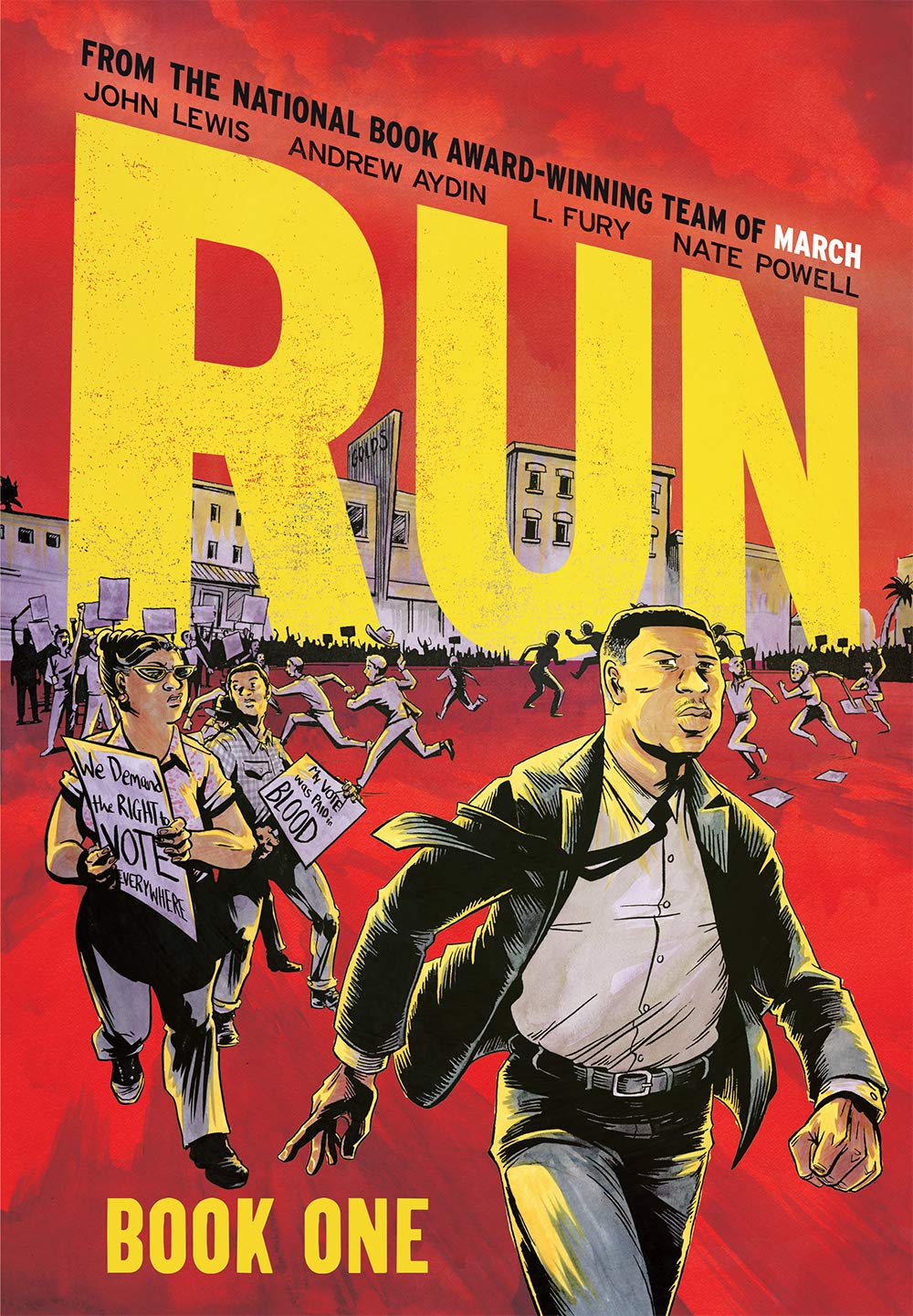

Run: Book One by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, L. Fury, and Nate Powell, with lettering by Chris Ross and Powell, is the highly anticipated follow-up to the March trilogy.

The graphic novel from Abrams Books is available today at your local bookstore or public library.

The Beat got the opportunity to speak with Aydin over the phone to learn all about how comics were already a part of the Congressman’s story, find out what finishing the graphic novel in the summer of 2020 was like, and discuss why remembering the setbacks is just as important as remembering the victories.

AVERY KAPLAN: Can you tell us about your personal comics origin story?

ANDREW AYDIN: I started reading comics as a kid. Actually, my first comics I ever read were my uncle’s. My grandmother had saved them from when he was growing up, and she kept them under her office desk. I would come up to visit my grandparents during the summer. So one day, she was trying to entertain a young boy, about eight years old, and I love to read.

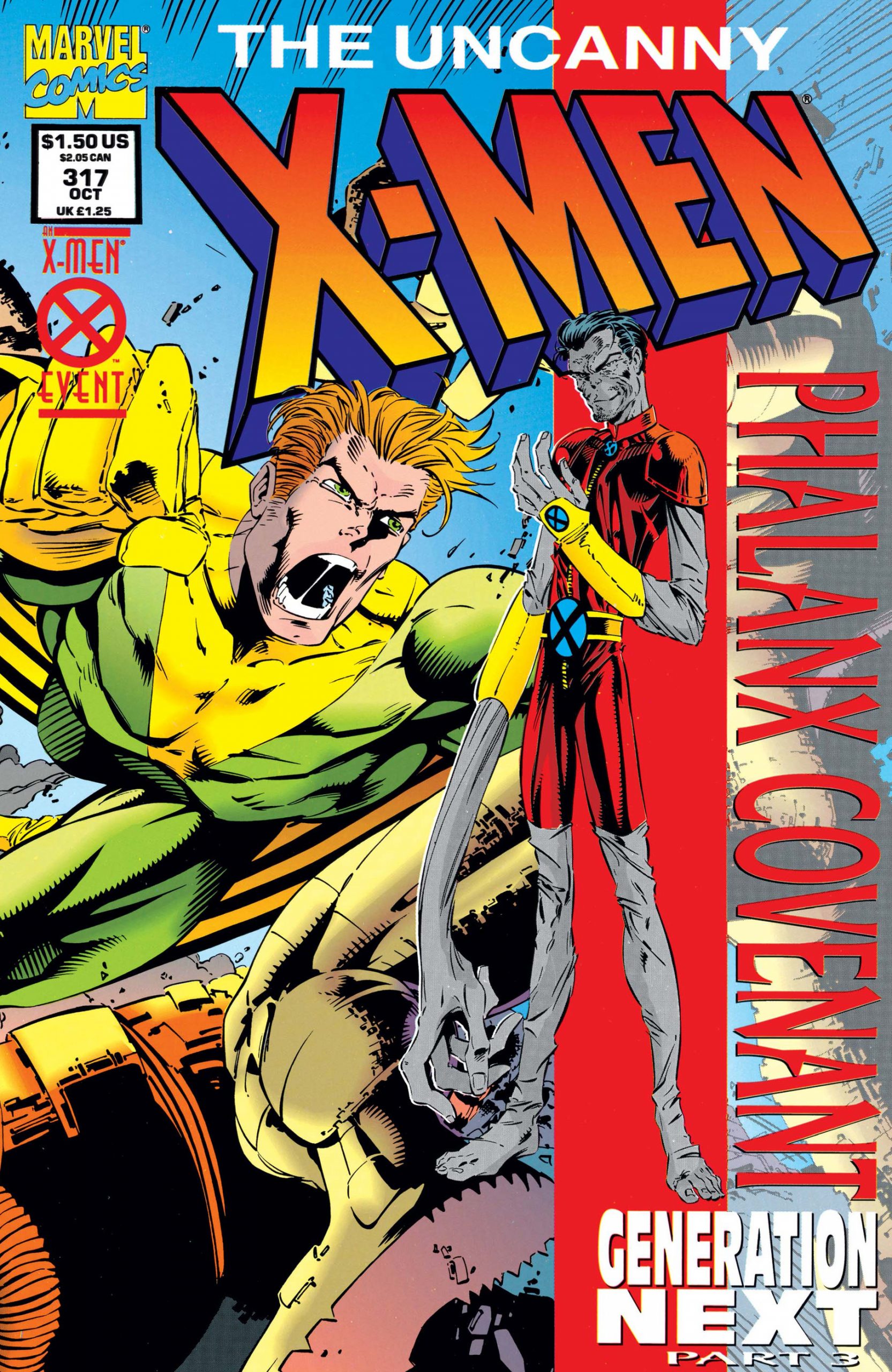

So she brought up the comics, and so I started reading them I got really into them, and then… There was a Piggly Wiggly in western North Carolina and my grandmother bought me my first comic – it was Uncanny X-Men #317. It had the lenticular cover… And I was hooked.

I started reading Uncanny X-Men and that was all leading into the Generation X comics, and then the Age of Apocalypse, and everything like that. And then I started really getting into the Mark Waid/Mike Wierigo run on The Flash, and then the Ron Marz run on Green Lantern. And that was really sort of where I started.

Then a few years later my mom let me go to Dragon Con. She let me go by herself, she packed me up with like, I’m not even kidding – I had a fanny pack with one of those brick cell phones in it. I was like 12. She was a properly nervous mother sending her child by himself on the MARTA train downtown. I had to call every hour to check in, and all this sort of stuff.

But I remember going to this convention, and getting to meet Mike Wierigo, first of all, that was a big deal to me – he did a Flash sketch on a backer board. And I remember really just kind of falling in love with the lifestyle that these creators had, not because it was glamorous, or because they made a lot of money – which they didn’t.

It was because they were able to make a living purely based on the power of their ideas. That what they dreamed up in their mind, and what they created was able to give them a living. That sort of freedom, that sort of independence… You know, for all its challenges, for everything that comic freelancers in particular go through. It was incredibly liberating, as the Congressman would have said, to see that there were people out there who love the same thing that I love, who gather together to celebrate essentially their love of reading, whatever the media may be, but they were gathering together because they want to read these things… And that there was a path to live a life doing this.

It was so eye opening to me, and then it stayed with me. I went to Dragon Con almost every year after that. And a lot of the people I would go with they became like family. It’s important to understand that that relationship that I had going to comic conventions, and Dragon Con in particular, was where the Congressman found his entry point as well.

Because it was during the 2008 campaign, folks were started to talk about what they were going to do after the campaign was over. You know some folks that they’re going to go to the beach and some folks said they were going to go see their parents and I said I was going to Dragon Con.

And everyone laughed at that, except for the Congressman, who said, “Don’t laugh, you know, there was a comic book during the movement that was very influential.”

That was the first time I heard about Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Montgomery story. And that’s sort of where the idea for March came from. I pitched the Congressman on it, that’s a whole other story, but him really embracing the idea started in 2009 in particular, once we were starting to work on him understanding this community.

He came about in 2009 when he first attended Dragon Con with me. I was going to be down there, you know, his office was just down the street, so he’s like, “I’ll meet you for lunch.”

So the Congressman and John-Miles, his son, came down met me for lunch at the Hyatt. And I remember him just kind of having like saucers in his eyes, just watching all the people come through in costumes. You know, he was asking all these questions: “Who is that,” and I’m like, “Well sir, that’s a Wolverine.”

And that was kind of how he started, too, right – it’s this through-line through it all. And of course, he goes on to become a beloved part of comics and go to all these conventions, even cosplays as himself. But that’s how it started.

KAPLAN: Comics play a role in the narrative of run in more ways than one. Can you share a little bit about how comics were already a part of the Congressman’s story?

AYDIN: Well, the Congressman remembered Martin Luther King and the Montgomery story from when he was a part of the movement. And he remembered the comics that they were using in Miles County. And he also talked to me about (and I later talked to Julian about) the fact that Julian Bond himself had written a comic book in 1966 to explain his opposition to the Vietnam War.

So there’s this incredible history of comics during the civil rights movement, but I don’t think it would be fair to say the Congressman was like a comics reader back then. When you’d ask him that question he would say something like, “You know, we were so poor, I couldn’t even afford a subscription to the newspaper, much less going to buy an actual comic book.” But he would read the comics in his grandfather’s newspaper that they would take like a hand-me-down a few days later.

He was so funny. Because after that first Dragon Con, he would save the newspaper articles for me anytime there’s something about comic books, right? Here’s John Lewis in his congressional office, reading the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal or the Atlanta Journal Constitution – he would read a lot. He was he was a voracious reader. And he would pull them out, or rip them out or save the section, and show them to me. And I think over time, he really came to know quite a bit about comics themselves, and especially once he started going to conventions and meeting a lot of these people.

I’ll never forget when he met Stan Lee. I don’t think either one of them knew who the other one was until after they took the photo together… But we were standing waiting for a car to pick us up in Las Vegas because we were there for the American Library Association show, and up walks Stan Lee with someone else waiting for his car, and Nate Powell’s with us, and we kind of look at each other like, “Oh my god, that’s Stan Lee.”

And so John Lewis is always a wonderful opportunity to introduce yourself, right? I’m like, “Congressman, you really need to meet this person – this is Stan Lee.” And Stan goes into full performance mode: “Hey, how you doing guys!”

And I’m like, we’ve got to get a picture! So they’re shaking hands, they look like brothers, right, so happy. And then afterwards I’m like, “Okay, Congressman. That is a guy who helped create the early Marvel universe and all the Marvel characters.” Then Nate and I started getting into, “But there’s Jack Kirby. He also played a huge role.” And he’s like nodding like, “Oh well I’m glad I got to meet him.”

I mean, you want to say he was such a good sport… but it wasn’t like we were talking him into this. He got excited by it. When we would go to San Diego Comic Con – because he couldn’t go every year, it’s a lot of work in logistics to get him there. So when there wasn’t an award ceremony or new book or something like that he didn’t go… but he would call us, he would usually call me in the middle of the convention. Always being like, “How’s it going? What’s happening out there? Are you getting into trouble?” And he wanted all the gossip about like, “Well, you know, people are saying this about the book, and I met so-and-so and they seem really excited about it, we’re gonna follow up.”

And he’d be like, “Well, I’m sorry I can’t be out there with you,” it was so telling, you to hear in his voice, he was like, “I wish I was there.” He just he just loved it.

I mean, and I think it’s important to remember to how much comics loved him! You know, you would see celebrities walk the floor. And they’d have a little security detail around them, and people would be pushed back and whatever. But John Lewis would walk the floor and he would shake every hand. He would get hugged, and people would start crying, people would want autographs and selfies…

And even sometimes, he didn’t quite know who it was. I remember one time we saw Lou Ferrigno, and he was in his booth, and he says, “Congressman! Congressman!” and like waved at him. So the Congressman goes over, shakes his hand, and Lou’s sitting at his table, so he was sitting down so you don’t see the full breadth of this massive man.

And so he shakes his hand I snap a quick picture and then keep going, an he asks, “Who was that?” “It’s the Hulk!” “Hulk? That’s really nice, I never met a Hulk before.”

He was very matter of fact about all of it, and I guess that’s the thing, right? It would be so easy for him to have an eye, it would be so easy for him to slip into, “This is what I’m supposed to do, and these other things are not things I’m supposed to do.” But he was such a curious person who loved people so much, and was so devoted to the cause of telling the story, of bearing witness to what happened during the Civil Rights movement, that he felt like comics and comic readers, and this community were just another avenue that he had to pursue, even when other folks didn’t understand what he was doing.

And the story he always loved to tell about this was: we were at a book signing. And our book signing lines would get quite long – I mean they could be two-, three-, I think one time we even did a four-and-a-half hour, five-hour signing. It was nuts. He was so good about staying until the end, signing every book he could.

So he had this young little girl who comes up to him. And she says, “I read Book One while I was waiting in line, and I really have one question for you.” And he was so serious when young people would come to him, so he’s looking her in the eye, he’s holding her hand because they’ve been shaking hands, and she just deadpans straight to him: “Why are you so awesome?”

That was what he loved. He knew you always had to be doing something new and different to keep telling your story, because people change, times change, preferred outlets change. And he embraced so wholeheartedly, and then to see the young people embrace him… That was, I think, one of the things that made him happiest of anything he was doing.

It was a wild, wild world, I tell ya. With him, we had so much fun.

KAPLAN: One topic raised by Run is the origin of the phrase ”Black Power.” Why is it important to study the origins and evolutions of linguistic phrases?

AYDIN: I think it’s incredibly important to study these origins, because that’s how we understand what they really mean.

If we don’t understand the phrase “Black Power”… Sometimes it’s cast in a negative light, sometimes it’s cast in a positive light by different groups, and you have to understand the full context of it, so that you can really understand what that phrase means… and how it came to be ubiquitous and a rallying cry for many, at that point the movement.

KAPLAN: One element of brand that may surprise readers is the fact that the title page displays a KKK march. Was it important to show how white supremacy utilizes similar techniques in an attempt to accomplish opposite goals?

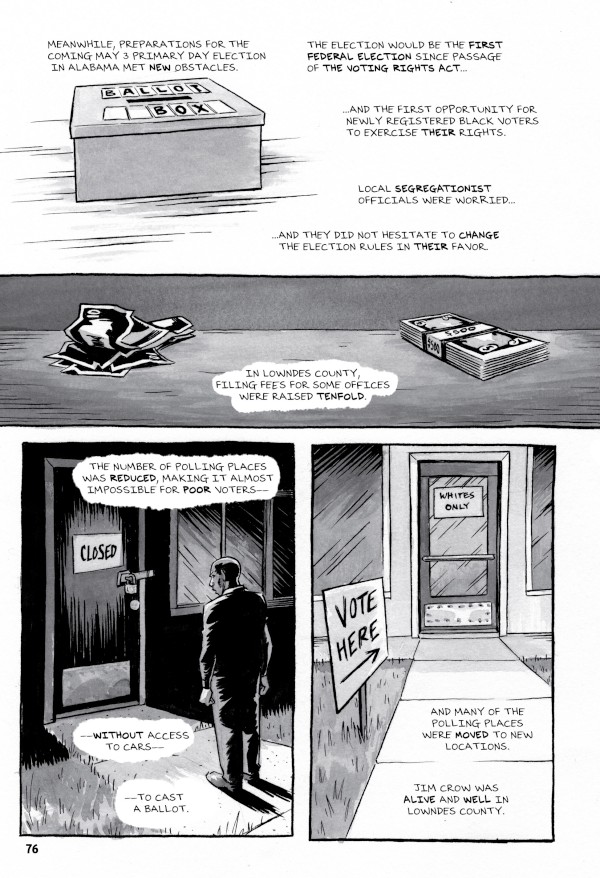

AYDIN: I think that’s a fantastic question, because what we were trying to do is to show that the tactics – the ways in which the movement organized and protested and successfully made their case – were almost immediately, after the signing of the Voting Rights Act, being co-opted and utilized by the Klan and by the forces of white supremacy to fight back and to also undermine that progress.

I think that’s an incredibly important lesson for us today, because I think about social media, for instance. In the early days of social media it was used as this incredible progressive organizing tool. Think of the rise of Howard Dean and even Bernie Sanders, fueled in many ways by social media.

And yet today, a lot of social media is being used for propaganda, for disinformation, for sowing discord. It’s another example of how something that was used by a progressive cause successfully was co-opted in different instances.

The reason we open the book in that way, and why that scene is so important – which is a scene that’s largely absent from most histories. Why that scene is so important is because It dramatizes exactly how immediate the backlash was, and the co-opting of the tactics of the movement was.

KAPLAN: In the opening of Run it is stated that work on run began in 2016, and that most of the pages for this book had been completed by the summer of 2020. What was it like to be concluding this volume around the time that the George Floyd protests/Black Lives Matter demonstrations were taking place around the world?

AYDIN: The Congressman would say, when something happened in the world that seemed to make our work more important, he would say, “The spirit of history is with us.” And I think over and over again in that spring and summer, I felt like the spirit of history was with us.

Because there’s so many elements that we included in Run that we didn’t know whether or not they would be relevant by the time they had been illustrated and worked on and everything. For example, you know, we discuss the use of the word “riot” in connection with the “Watts Riots,” as they call it. We say is, “Is it a riot or is it an uprising?”

When you realize it was written so, so much further in advance of what happened… It becomes another example of the spirit of history of being with us, where we are raising these questions on intellectual level with each other, and putting them on paper, and then the public faces the same question that we were debating.

Another example of that is a statue of the former US senator who was vehemently against American involvement in foreign wars, but was treated as a hero, and given a statue and remembered, even though he was a virulent racist and a Klansmen. And to show the juxtaposition with what was being done to Julian Bond at the time but also as we’re dealing with… I mean, you could say it goes further back than Charlottesville, but this this recent growing awareness of how our monuments and statues have been used to reimagine history and create a narrative that people accept that’s not true.

I think as we as we worked on this, especially at that point, because the Congressman is so sweet – he was a lot of people who wanted to be with him, and a lot of people we hadn’t seen in a while, and I was trying to stay out of the way a little bit. You know, you don’t want to be the… I don’t want to get in between those folks, you want to give him his time.

But he was so insistent that he would hide the documents or the pieces of paper with his notes on it behind the planter on his front porch, and I’d come pick them up. Then I’d bring back new stuff have it put under the door in his mail slot, and we just had a little system. In some ways I think it was very difficult to see that is also incredibly encouraging…

I mean, he went to see Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington, DC, in front of the White House. And when you look at how they did the lettering of it… We talked about it. It looked just like the cover of March: Book Three, and how we had “March” laid out on the pavement of the Edmund Pettus Bridge… a reminder that art plays a significant role in influencing our politics and the national conversation. I think in many ways that also reinforced our commitment and the necessity of doing what we’ve been doing.

KAPLAN: A repeated theme and run is that in spite of having a righteous struggle and righteous goal victory is not always attained, especially not immediately. Was it important to show this aspect of the Congressman’s journey in this volume?

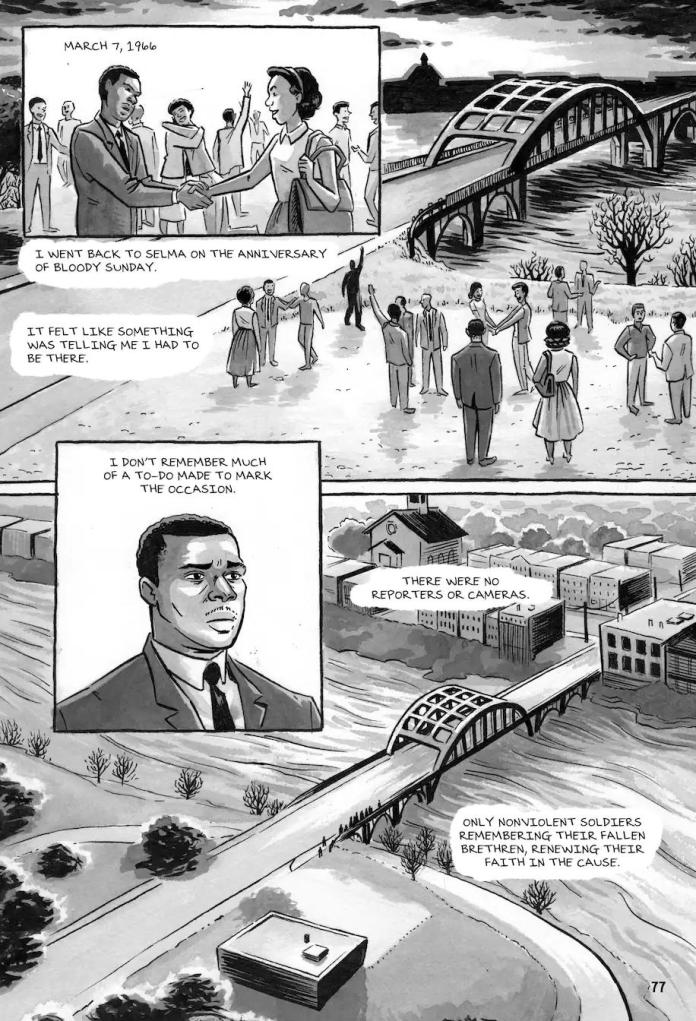

AYDIN: Absolutely, I think it’s incredibly important that we show the setbacks as often as we show the victories. Because I think, again, this year, the last few years, have taught us that you can get a great win, and then you can be pushed back.

No victory is guaranteed in perpetuity. We look at what’s happening to the Voting Rights Act, and how it used to be bipartisan to reauthorize this, and yet the Supreme Court strikes down a portion of it… Congress fails to reauthorize it… and now you see this almost outright rejection of guaranteeing every American citizen an equal opportunity to participate in a democratic process. I think that’s all we have to show.

For me personally, it was always interesting to see the press, academics, and so many people would focus on the victories, and miss the fact that what made John Lewis so special was the fact that he kept coming back, win or lose. It was his commitment. It was his militancy and devotion to the cause. And we have to show how even our greatest heroes face incredibly difficult setbacks, because we all need to know that for our own sense of perseverance, for our own ability to comprehend what’s happening around us.

I think one of my greatest fears is that John Lewis will be put on a pedestal and his Truth will be forgotten, who he really was. And that’s the guy like to go to Comic Con, that’s the guy who stood up to people, that’s the guy who really took risks in his life in his whole life. He wasn’t afraid to fail.

I remember one time they were considering replacing the superintendent in Atlanta. And he was up in arms, he was adamant, “Please don’t. I think she’s fantastic.” And he wrote all these letters and he made all these phone calls and he did everything he could, and they replaced her anyway.

That’s the real John Lewis. A person who is unafraid to stand up for what he believed in, whether or not he was going to win. I mean, think about his support his opposition to the defense of marriage, he was opposed to DOMA before anybody else was willing to take that risk. This was like, ’92, ’94, he was speaking out against it, he called it cruel and wrong. And it wasn’t politically palatable, in the way that it is now. But he didn’t care, because he knew in his heart and believed in his heart, that that was the right thing to do and a moral position to take. And he did that over and over in his life.

KAPLAN: I’m desperately missing comic conventions. Can you share one of your favorite con stories about the Congressman with us?

AYDIN: I got a bunch!

My most precious memory is the children’s march, that we led several years, and how excited he got to cosplay as himself. I remember helping him get dressed that morning, Nate and I were in his hotel room he’s trying to get the coat on the backpack and make sure everything is right. And he kept asking, “Am I doing this right?” It’s absolutely priceless. The sincerity that he brought to this, to comics.

It’s funny, people forget. So you had this great big day in 2013, where we took this huge risk. And he shows up at Comic Con, and it works, press mob him, we get all this coverage. Everybody’s toasting the book at Comic Con, nobody’s really seen a nonfiction graphic novel like this before it was just a hugely successful day and it had been at as long as the end of this long journey, where you don’t know if it’s gonna work, and you’re hoping and praying you haven’t just humiliated your boss on the national stage right.

So we’re feeling good and we’re finally walking away from the convention center. We’re thinking about going back to the hotel and the Congressman says, “Do you know if there’s a Nordstroms here?” Like, matter of fact, I do, it’s just up the way. “Why don’t we go to Nordstrom?”

We’re walking through Comic Con, you know how you cross up and over the train tracks, and then you go up the hill, sort of towards Ralph’s, and then there’s the Nordstroms – or it was, I’m not sure if it’s still there.

And we go, and he’s looking at socks, because he always like to have fresh new socks. Especially because he liked to wear colorful socks, because he always wanted look fresh, and look clean.

So we’re in the Nordstroms, and one of the clerics walks by, and he’s like, “Hey, aren’t you that Congressman with the comic book?” Because he just seen him on TV. And then he kind of looks at me and he’s like, “And you’re the aide, right?”

And we’re looking at each other. We’re like, “Yeah,” and he’s like, “I’m John Lewis,” you know, and then he starts… The clerk must have been a 25-30 year old black man, and so [the Congressman] started to tell him about Selma, and he’s giving him this, “Yes, I walked in Selma with Dr. King,” just giving him the whole history.

It was incredible to me because it was such a moment of seeing how the comics boosted hit the awareness of what he did almost immediately. That has been one of the persistent challenges that I heard in the congressional office over and over and over again was, “How do we teach people the full extent of what it is that John Lewis did both during the movement and then later in life.”

And there was, clear as day… At a Nordstroms in San Diego, while the Comic Con is going on. And then he bought some socks, he bought me a new tie, and we went back to the hotel. And then, there was a pizza party that night.

There’s actually a whole story about how the Marriott gave away his room, because he got into late, And there was this terrified moment of us being like, “Yo, John Lewis is landing in an hour… do you have a hotel room for him?”

They were super apologetic and so they put him in a room at the Hyatt, and the next night they gave him kind of one of those big rooms at the top of the hotel. It was so big he was like, “I can’t stay here by myself.” So he invited everybody from the publisher up to the room, and we all ate pizza. We just had a pizza party with John Lewis in his hotel room.

It wasn’t like it was just a bedroom, it had a living room and everything like that. We’re all hanging out, sitting there having all these conversations with the different comic creators.

I remember leaving, he had a grease stain on his shirt because he’d been eating all this pizza, and no one said anything… I don’t want to point it out, you know what I mean. Pizza! Who cares?

When he left to go to the airport, to fly back that night. And then this silence kind of came over the room, and it started to sink in to everybody there. What really just happened… That they had a pizza party at a comic book convention with one of the most important figures of the 20th and 21st century.

And that is why John Lewis was so special and so important, because no matter what award he got, no matter what fancy person, what president, what leader, Head of State said about him, praised him for, he was just a human being who loved other human beings. And that manifested itself in ways like that.

And in that moment, he was just another comic book writer, along with everybody else. He didn’t think of himself as special. He didn’t think of himself as above anyone. And that allowed him to connect with people in a way that few other people can.

Can you tell us about Truth and Justice #6?

I wrote Truth and Justice # 6 for DC. Here’s the fun thing: I’m half Turkish. My father was a Turkish Muslim immigrant. And when Damian Wayne came along and they started making him a character I was always like, “Yo, Batman got a half Turkish son.” Because Talia and R’as, they’re all from what they would call Eastern Europe, Eastern Ural, which is essentially Turkey, right, is Anatolia.

And so DC let me write a story that makes it canon that Batman’s son is in fact half Turkish, and I got to introduce two new superheroes. They’re the Hittite gods – which are real gods, it’s a lot like Thor and Loki, but they’re from Anatolia, they’re not the Norse gods, they’re the – I call it West Asian, because I feel like “Middle Eastern” is a colonialist/colonizer term.

I introduced all of that, and I’m really proud of the issue, and I’ve been sort of shocked because I can’t find copies anywhere and everybody’s telling me it’s sold out! They sold all the copies I can’t even order it from Midtown, you can order anything from Midtown.

I’m really proud of that, I think for a lot of us who are mixed race, we don’t have heroes that reflect us and being able to have it be organic, just using the storytelling to flesh out the background a little bit and have… The story though about Damien confronting the fact that he is from both worlds. He’s an al Ghul and a Wayne. And I just, I’m just super, super proud of it the reviews have been great.

Juni Ba, the artist is going to be huge. He’s a fantastic talent. He’s got that other cool book out right now called Djeliya. And I think, you know, the fact that it’s sold out, like the kind of guy here said all my speculators bought it, it’s a first appearance, major moment for Damien. And I’m sort of just like getting to live my childhood dream, “Hey look, I just made myself just like Batman’s son.”

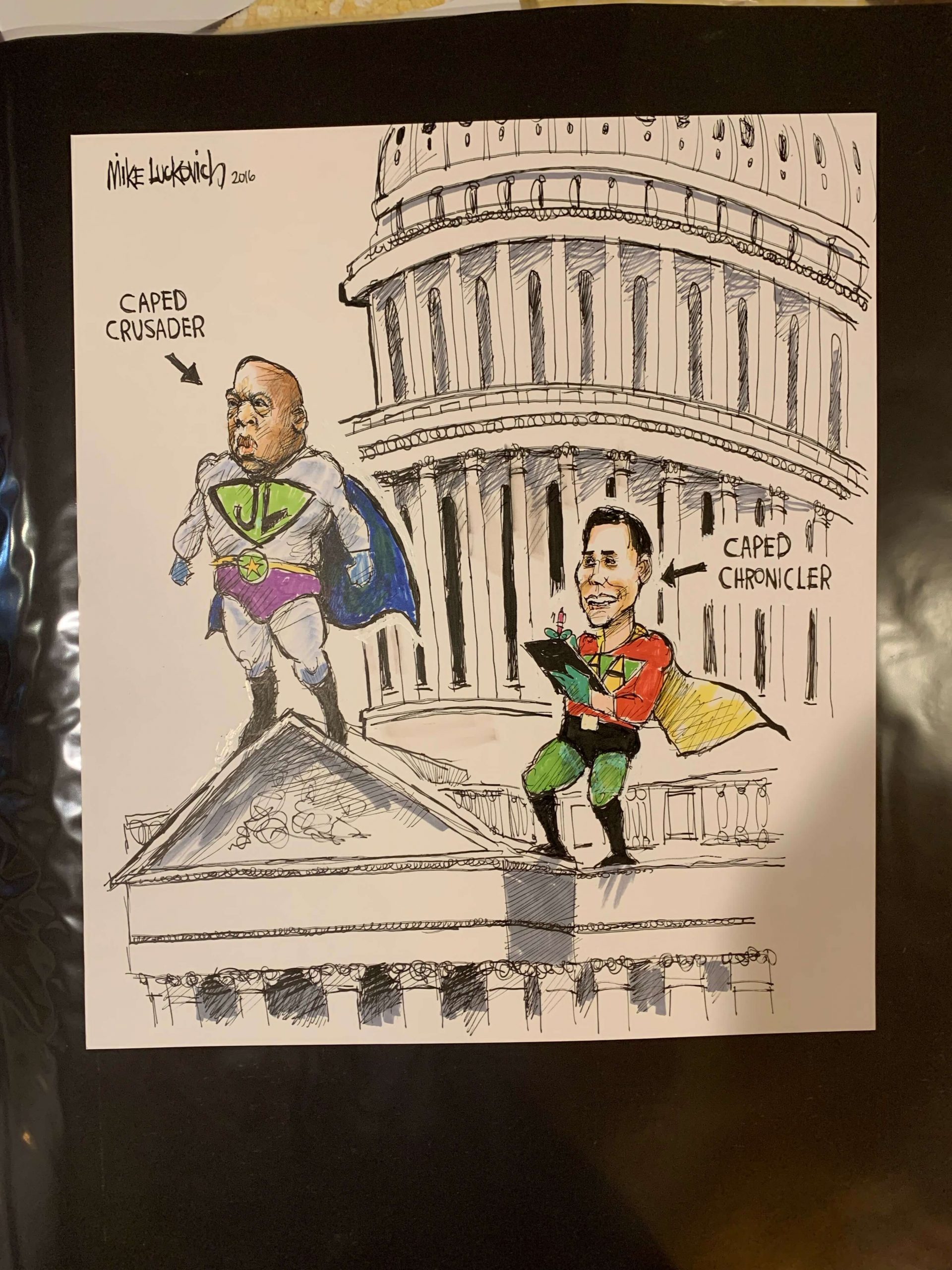

You know, I used to joke… Mike Luckovich is a political cartoonist for the Atlanta paper, and he drew a cartoon of me and the congressmen were he’s Batman and I’m Robin. So it’s full circle for me, you know?

KAPLAN: Is there anything else that you’d like me to be sure to include?

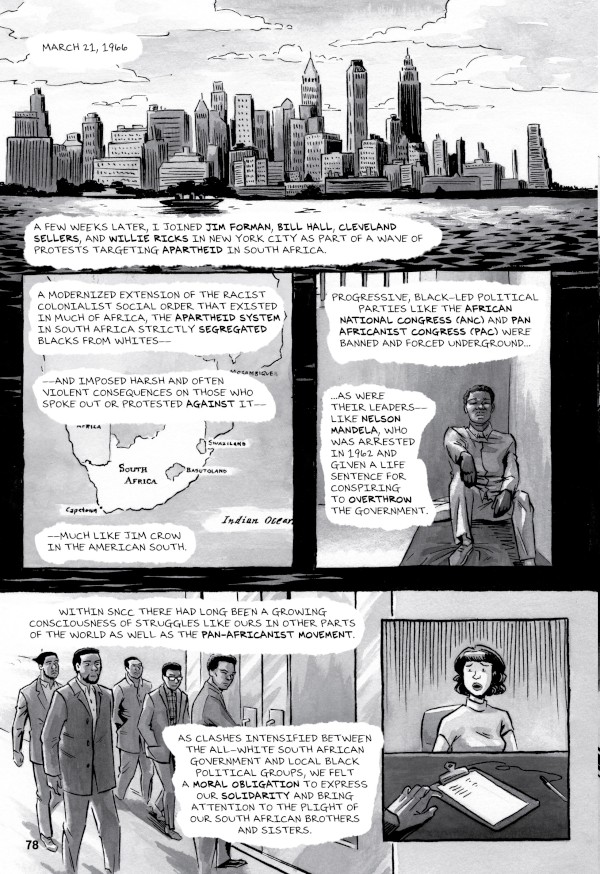

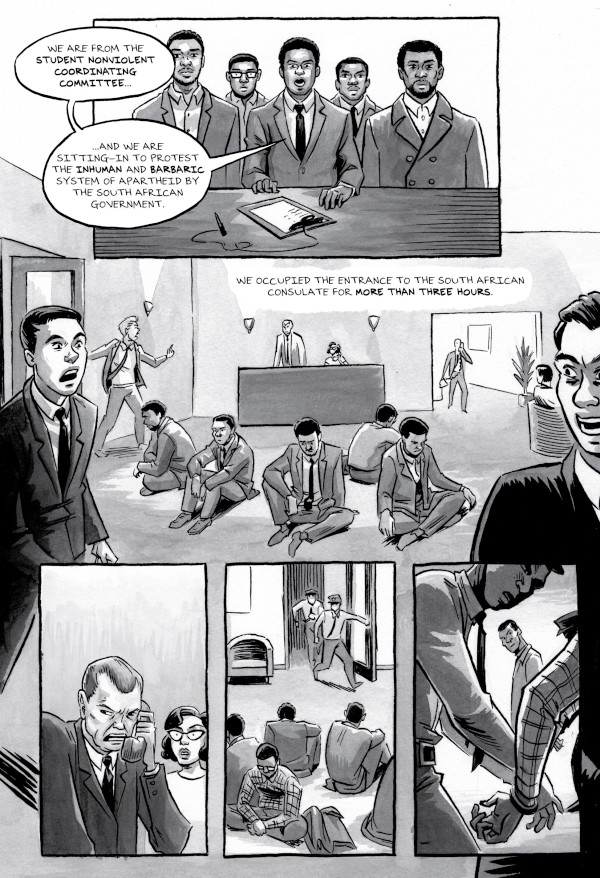

AYDIN: I think it’s worth a mention that we shine this light on the comics that SNCC used in Lowndes County, because I think there’s always still that question about whether or not comics are a viable means to creating the climate and the environment to create social change.

What I hope we’ve shown both through March and Run is not only can they work… Not only did they work, and play a meaningful role in the civil rights movement, but drawing that inspiration allows us to make these new comics, these new graphic novels, that can play that same role and in some way, even play a bigger role in inspiring the young people of today, because now comics are in the classroom. Now you can teach these stories.

I think as we see the state of Texas banning the discussion of many of the events and topics that are in Run and are in March, it is incredibly important that we fight for these books because they are going to be the link to John Lewis and to the past, that is available to young people that works, and it keeps his memory alive and keeps these tactics alive and keeps this understanding alive. And I think that fight, that battle, is playing out across the country.

We used to have this this – it was a suspicion. We’d talk about it but we never really found a way to articulate it, but there were always obstacles to March where you really felt like there was institutional opposition to teaching anything about the Civil Rights Movement. And now I think the quiet part is being said out loud and we’re really starting to see it was always there.

What happened was March was remarkable, not just because of the fact that it worked but the fact that it worked in spite of this opposition. And now, if we don’t keep fighting for it, keep fighting for these books to be in schools keep fighting for these stories to be told you showing them to young people, they will be lost, and we won’t be able to make our country work, to make our democracy sustainable, if we don’t continue to teach these stories to young people… and to people not so young.

I know way too many people, but who are adults who don’t know, these stories who don’t know that history. And comics and graphic novels are our best weapon, our best chance to reach the most amount of people to give everyone a common language with which to discuss the events of our lives as they’re happening in front of us.

Run is available at your local bookstore and public library today.