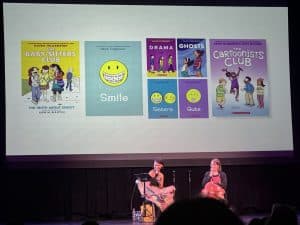

On a cool (for the desert) evening at the Madison Center for the Arts in Phoenix, AZ, Raina Telgemeier kicked off her latest book tour for Facing Feelings to an audience of eager fans. Based on the exhibition at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio State University, Facing Feelings marks another milestone for the author of beloved works like Smile and The Cartoonists Club. the latter of which came out earlier this year (co-written with Scott McCloud).

The crowd was varied and enthusiastic, with an electric atmosphere especially among the young readers clutching their copies, ready to delve into Telgemeier’s latest work. The discussion was moderated by fellow author-illustrator LeUyen Pham, who openly expressed her admiration for Telgemeier’s groundbreaking debut. Pham described Smile as “like Persepolis, but better” and referred to it as a “book of the ages,” a testament to the graphic memoir’s lasting influence on young audiences.

Throughout the evening, one particularly spirited young fan in the front row captured the essence of Telgemeier’s loyal readership, eagerly attempting to gain the author’s attention. During the conversation, Telgemeier shared her artistic philosophy: she aims to convey the essence of experiences rather than merely their visual representation, an approach that has struck a chord with millions of readers who find their own feelings mirrored in her work. When asked about her favorite book among her creations, she answered without hesitation: Smile holds a special place in her heart.

Even though the formal talk had ended, the excitement was still clear. The line to take a photo with the author was long (attendees received a pre-signed book), filled with excited fans who were looking forward to meeting an author who has changed the world of middle-grade graphic novels.

Before the book talk, The Beat was able to chat with Raina regarding her recent books, the relationship she has with her readership, and her creative process.

AJ FROST: I wanted to start by asking about your book The Cartoonist’s Club. It’s such an impactful graphic novel that blends a compelling, inspiring story, and creative guidance. How’d you keep it emotionally real while still teaching the craft of comics with your co-author Scott McCloud?

TELGEMEIER: We made drafts, and I think I was the one sort of keeping the emotional heartbeat going, while Scott was busy keeping the science and the spirit of comics explanation going on. Between the two of us, we were balancing each other out pretty well.

I could tell the parts that were “Raina” and the parts that were “Scott.” Scott was also trying to lean into the characters and the emotional aspect of it, because he knew that’s what we were going for in the book. So, his first draft was also going for character interaction, friendship. He actually wrote a pretty strong love story. It was me and the editors who were the ones that said, “Whoa, this is a lot, Scott.”

FROST: You know, each character faces some sort of creative block: doubt, perfectionism, pressure. Which of those felt closest to your own experiences?

TELGEMEIER: I think each of the four arcs was personal to both Scott and me in a way. Each was resonant to both of us for different reasons. Linda’s always gonna be the closest to me because she’s the closest to an autobiographical cartoonist. Her story is not my story, but her struggles with self-doubt and sharing herself on the page look a lot like me sharing my story in Smile and putting it out there in front of people. Wondering if people will want to read my diary or judge my artwork for it.

But I also, like Howard, sometimes doubt that I have storytelling chops. I like to draw; I don’t know if I like to write. Like Mikayla, I often have too many ideas and not a clue as to what to do with all of them. And I like to doodle. So I think Scott, too -– and I won’t speak for him -– but I think he can see himself in these characters. He can definitely speak from the point of view of Miss Fatima, who will gladly lead you on a journey through time and space and possibility.

FROST: You touched on this, but Scott is distinctive in how he approaches his comics work. What do you think that collaboration taught you about your distinct voice, his distinct voice, and the storytelling process in general?

TELGEMEIER: What’s interesting is that I’ve been reading Scott’s work since 1993, and he and his family have been fans of my work for a really long time too. So we had our fingers in each other’s pies for a long time before we started collaborating, and had been scholars of each other’s work. I think the influence had already started to cross over.

And it was wacky, then, to write chapters and then trade them between the two of us and then write over each other. I felt ashamed to cross out lines of dialogue and rewrite them or suggest edits. Who was I to edit the great Scott McCloud?

But all of it was in service of story. All of it was in service of making a better book together; we had our editors doing the same thing. A lot of times, one of us could see something the other could not, or one of us would have a stronger opinion about something than the other. You know, “I just dashed that off” or “that was just written as a placeholder.” You write badly so that you can fix it, right? That’s what a first draft is supposed to be.

So, we wrote three drafts. The first draft was pretty much thrown into the garbage entirely, but it led us to a second draft that everybody liked a whole lot better.

FROST: You’ve said this book is for classrooms and young creators. What do you hope it helps them believe about who gets to make stories?

TELGEMEIER: I don’t want them to wait. A lot of kids ask, “What do I do? I want to be a writer someday.” And I say, “Start today!” Or they say, “I’ve already written stories. I guess I want to be a writer,” and I’m like, “You’ve already written 67 stories? Then you are a writer. There’s no tomorrow. It’s today.” Write a 68th story! Have someone else read your story, give you feedback. Just keep writing.

FROST: That’s great advice, and that’s what I was trying to say in my review from earlier this year. It’s easier to get stuff published than ever before; there are no gatekeepers for everything anymore. You can be direct to the consumer or just for yourself. If someone was to be like, “Oh, I want to do this,” would you just say, just go ahead and do it?

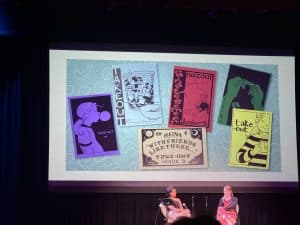

TELGEMEIER: Yes, I would. The other thing is that publishing is not necessarily the goal. I know that sometimes kids, and especially their parents, feel like something has to be published in order for it to count. That’s not necessarily true. I self-published for years, and to me there was a lot of satisfaction in just making something that I can hold in my hands.

We talk in the book about making mini comics – that’s something you can make with a single piece of paper, a couple of staples, and a pencil and your imagination. And it’s really satisfying just to have that and just to show it to somebody and say, “Look what I made!”

FROST: Moving on to Facing Feelings – you’re out here, you’re on tour. How does connecting with fans in person influence the way you think about your work in a broader context?

TELGEMEIER: Well, this is my first day of tour [on November 6, 2025]. And the really lovely thing about this particular tour is that I get to share the stage with friends. We’re here reflecting on kind of the past twenty years of the industry and the friendships that we’ve built along the way, and what the beginning of that industry looked like when all of us were going, “What could this possibly be? What do we want it to be?” And where we are now and what the landscape looks like.

We were just a bunch of young artists with dreams. And now we’ve made a bunch more artists, and a lot of them have big dreams too. So we just get to share that space together. A little bit of looking back, and it’s really beautiful.

FROST: How did you decide which parts of your journey to share for the exhibit and then for the book?

TELGEMEIER: I’m really lucky to work with the curator of the exhibit, Anne Drozd, at the Billy Ireland [Museum of Comic Art at The Ohio State University]. She had a vision for it, and she came and spent a week in my studio and went through all of my artwork. She already had the idea at that point for the lens of the six primary emotions and sorting my work into those six categories: joy, anger, sadness, surprise, and so on. So she made six piles, took photos, made a big spreadsheet document, and then shipped them all back to Columbus and then figured out what to do with them.

It was a bit of a mystery to me what she was gonna do and how she was gonna present it. But she did her work, and then she sent me a document, and it was such a surprise to me. I didn’t really know what it was gonna look like, but when she showed it to me, it just took my breath away. And seeing it for the first time on the walls – the second time it took my breath away. And seeing it again presented in the book, it is a surprise every single time I see it. I feel like it’s not even my own work.

I’m astounded by it.

FROST: Yeah, it must be surreal to see something that you drew when you were probably a child up on a museum wall.

TELGEMEIER: I also feel like I can’t take credit for it. There was so much hand-holding and having a direction for it.

FROST: Comics make the inner life visible. Why do you think that visual language invites such deep empathy from readers?

TELGEMEIER: I don’t know if it’s something about mirroring faces. When you’re talking to a friend and they’re sad and they’re making a sad face, you almost can’t help making that face back at them and feeling for them. I wonder if comics do that for the reader. When you see someone feeling sad in comics, you reflect that back, and so therefore you’re feeling what the character’s feeling. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but it feels right to say that.

And especially when you’re drawing something, if you’re feeling sad, you have to act through your character on the page. I often have to go through the same emotional arc as an artist. This is part of why it’s so hard drawing a very emotional comic book, especially a graphic novel. I have to drag myself through the depths of whatever the character is going through. With Guts, I have to live through a phobia and a traumatic experience over again. It takes me a year and a half to go through that as a writer and an artist. I’m strung out by the time I’ve finished writing it.

FROST: Right, or Ghosts, which was an intensely emotional book.

TELGEMEIER: Yeah, even though that was fiction. But you still have to lend a true part of yourself to something like that too. So I need a lot of recovery time and self-care when I’m done with a graphic novel. And then by the time I’ve recovered and feel like myself again, it’s time to go on a book tour. And then my young audience wants to talk to me all about these things or how heavy it was.

This is part of why it’s taking me longer now to write books than I used to, because I have to factor in all of that deep emotional process.

FROST: Well, that then leads to: with all that energy and introspection that you just shared, what are you curious to explore next?

TELGEMEIER: Oh my…. The wheels are turning, but I haven’t quite come to the answer to that question yet. I gotta finish this book tour, gotta do some life-y stuff. And I hope to get into that in 2026, New Year.

The Cartoonist’s Club and Facing Feelings are available now from Scholastic/Graphix.

Good Interview!

Comments are closed.