X-Men: First Class does something I haven’t seen a superhero movie do before. It’s not just a period piece, that’s unusual enough, but it also places its fantastic characters, Gump-like, in the middle of historical fact. Captain America: The First Avenger, released concurrently, went back in time to place its difficult-to-like protagonist in his proper context, but then wove a fantastical story around him involving ancient Norse artifacts and a guy with no face. First Class not only places its characters in history, it puts them at the center of the darkest, most traumatic events of their time.

That kind of treatment skirts the boundaries of taste, turning, for instance, the Holocaust into comic-book fodder: First Class almost runs into Inglourious Basterds in its treatment of history. No one goes to the movies for a history lesson, but movies have always taught us, from their inception, through their dream-logic, who we are as a people and as a culture. It’s not the job of cinema to tell us how things are but how things feel. You can say that First Class tastelessly warps WWII, but Triumph of the Will did that before anyone even knew what WWII was. The Bryan Singer X-Men movies cloaked their tales of discrimination in colorful metaphor, but First Class demands to be considered “important,” and, to an astonishing degree, it succeeds.

We begin where we began the first X-Men movie, way back when, with young Erik Lehnsherr, a Jewish boy, being separated from his parents at Auschwitz. It’s a primal scene, a boy separated from his parents, the sort of scene that forms the spine of a Spielberg movie, given added weight by its being rooted in history. By separating Erik from his parents in a prison camp, by actual Nazis, the movie gives him a historical resonance — he is now representative of a people, and not just a people, but a whole time.

Is that a good idea? Is that the business of movies, to take the central trauma of the 20th century and make it a superhero origin story, stripped of metaphor and presented as stern, cold-eyed drama?

Honestly, I don’t see why not. As I say above, movies have always done this. Birth of a Nation is no more historically valid, and quite a bit less tasteful at this point, than First Class. Many have argued that Schhindler’s List is tasteless too, and still others have argued that no representation of the Holocaust for the purposes of “entertainment” are valid. And yet, the Holocaust was a historical event — it involved real people in real places doing real things, and affected millions upon millions of people. If those events aren’t cannot be dramatized, how do we come to terms with them culturally? I can’t imagine a viewer who comes away from First Class thinking they’ve been an eyewitness to history, because the metaphor of Erik stays in place: he is a literal Jew during the Holocaust, but his suffering, and his destiny, are still tied to metaphor. He’s Superman, with his powers, only without Krypton. Can we absorb that, culturally, for what it is? It seems to me we already have. Moreover, it seems to me like it is a long time coming. In any case, the world accepted First Class without a squeak.

Young Erik, in his agony, bends the metal of the gates separating him from his parents, and he falls unconscious. At that exact moment, it seems, in upstate New York, young Charles Xavier, in his palatial estate, wakes up, awoken by an intruder. Xavier, we see, is the opposite of Erik: he is privileged, wealthy, a defender of his rights instead of a victim, startled awake instead of beaten unconscious. The parallel is made complete by having Xavier find that the intruder is his mother, as though, somehow, Erik’s loss is Xavier’s gain. But here the screenplay throws us a curve: Xavier’s mother is, of course, not his mother, but the young Raven Darkholme — Mystique. How does Xavier know his mother is not his mother? Because, apparently, Xavier’s mother isn’t a very good mother, and Raven’s doing a poor job imitating her. So the screenplay pushes the disparity between Erik and Xavier, then throws us a curve, then pushes through again, giving us two boys and their mothers, one who desperately wants his mother back and one who has his mother around but apparently doesn’t care that much for her.

Xavier doesn’t even blink when Raven reveals herself. Instead, he beams, making the disparity between him and Erik complete. Erik is the disenfranchised victim of brutal discrimination, while Xavier, the coddled youth, rushes to embrace the different.

While I’m on the subject of Mystique, her nudity here pushes the boundaries of taste in a different direction. The facts of life of a superhero — that you’re essentially always walking around naked — is made disturbingly literal with this character, who is naked even when she’s wearing clothes. That’s a winking titillation when the character is a babe in her 20s, but the little girl who presents herself to Xavier is just a naked little girl. And we are reminded that Mystique’s power, any attractive woman’s power, is in the hold they have on our attention. Mystique (as in “the feminine mystique”) is a mutant, a monster really, who presents herself as a sexually-charged beauty, uses her nudity as a provocation and a threat. Her beauty and nudity says “Come and get it” but her blue skin, yellow eyes and lethal disdain keep the viewer at a distance. To see this character as a little girl shows us, for the first time, and unforgettably, that Mystique’s anger and bitterness, her hard shell as it were, stems from being helpless and naked as a girl.

We’ve met our rich-boy, poor-boy leads, and our story will turn out to be a romance between them. Because X-Men: First Class is a love story, it is allowed two protagonists. Generally speaking, a love story is weighted in the favor of one participant or the other, but First Class‘s seems genuinely evenly-balanced. So, if we have our two protagonists, the question immediately rises: what do the protagonists want? Erik’s desire is clear, and stems from privation: he wants his mother back. Xavier’s desire, on the other hand, stems from comfort and plenty: he wants all those who are unusual to feel safe and welcome. (It’s an interesting question how safe Xavier feels in his estate, if his mother is cold and distant.)

But before we get to the love story we need to meet our primary antagonist, Dr. Klaus Schmidt. Dr. Schmidt, before he even sits down to speak to Erik, tells us that he is “not a Nazi.” He listens to Edith Piaf, pooh-poohs the Nazi goals of blond hair and blue eyes and offers Erik chocolate. He’s playing “good cop,” and in fact is positioning himself as Erik’s new father in this wartime drama. It takes a special kind of man to pretend to be a Nazi to the extent Schmidt does, and we will learn more about that later.

Schmidt wants Erik to move a coin with his special metal-manipulating powers. ”A little coin” he says. The little coin, of course, is a Nazi coin, complete with eagle and swastika, and will be linked later to Nazi gold, stored in Swiss banks. War, the movie reminds us, is often a business decision. Nations are invaded and people are rounded up and killed for the sake of profit. As of 1944, business is booming in Schmidt’s line of work, and the coin is the symbol of his power and arrogance. ”A little coin” is negligble, but we will see that there are things worth less to him.

Erik, unfortunately, cannot act upon the coin. The Nazi coin, Schmidt’s symbol of power, is too much for him. Schmidt rings a bell and, in a stunning reverse shot, we see that Schmidt’s cozy book-lined office also includes a huge operating theater. Guards bring in Erik’s mother and Schmidt unceremoniously shoots her dead and we learn that the key to Erik’s talent is, like Bruce Banner’s, anger. Erik, in his rage, destroys everything metal in Schmidt’s office, then kills the guards, then detroys the operating theater. He is now a murderer. He has gone from being a victim to a murderer. A righteous murderer perhaps, but still a murderer. He didn’t yank Schmidt’s Luger out of his hand and shoot him, and he didn’t even move the coin. And I’m guessing Schmidt knew all along that anger might be the trigger for Erik’s talent. He’s choosing a dangerous road for a volatile protagonist, and he gives him the coin as a kind of payment for the loss of his mother. He knows, he actually knows that the coin will keep Erik’s anger simmering at the boiling point, where Schmidt needs it to be. As it happens, this isn’t a dangerous road for him at all; we will find that Schmidt is uniquely suited to be the tormentor/mentor of a furious, metal-bending child.

In a nice little graphic metaphor, we see the Nazi coin in Erik’s hand become the main title of the feature. First Classimplies, in part, the “first class” of Xavier’s some-day school for mutants, but to find the X symbol on the back of the Nazi coin also implies that Erik and Xavier are, as the cliche goes, two sides of the same coin. One is driven by loss and privation, the other is inspired by wealth and privilege, but they are both wellsprings of, well, change, to make a metaphor a pun.

Now Erik is all grown up. We don’t know how he spent the rest of WWII under the tutelage of Dr. Schmidt, what we know now is that Schmidt has given birth to a revenge-fueled young man with impressive skills. He’s still got Schmidt’s coin, and it still fuels his anger, except now he is looking for Schmidt in Switzerland. He still has the coin, he never lost it, he still carries it with him and thinks about it. He can manipulate it easily now with great dexterity.

While Erik broods in Geneva, thinking about planting that coin into Schmidt’s forehead, paying him back, so to speak, for the price Schmidt paid for Erik’s mother, Xavier is at Oxford, using his incredible psychic powers to try to get a leg over with a comely blonde. Again, the contrast between leads on seemingly antithetical paths. Xavier’s youthful idealism seems to have stopped, for the moment, at Raven, who sulks in the background while Xavier chats up girls. We don’t know Erik got through WWII, but it’s even more remarkable to think how Xavier got from Westchester to Oxford with Raven following him around. Did he just announce to his mother one day “Mum, this is Raven, she’s a naked blue girl and she’s going to live with me from now on”? Did Raven want to go to Oxford, or is she a legacy admission because of her friendship with Xavier? For that matter, is Xavier actually smart enough to get into Oxford, or did he simply cheat on all his exams?

Xavier employs a lecture on mutation to seduce the blonde. This, of course, is nothing but exposition, put here for the benefit of confused viewers who have wandered in from the street, unaware of what the X-Men are. The screenwriter has done the wise thing and placed this exposition in the form of a joke, and in fact has the blonde call attention to it. Raven, who holds no patience with exposition or Xavier’s seduction techniques, interrupts.

What does Raven want? Raven, remember, is a horrible blue scaly naked monster. Xavier can expound all he wants on “mutant freedom,” the fact is that no society would ever accept Raven as anything but a freak. The reason being, of course, rooted in her power: she can create an alluring, deceptive appearance, but it’s only disguising her true appearance. Raven must be always naked, exposed, and simulatanously always in costume, pretending to be someone else.

I love what the screenplay does next — it sends Raven home to brush her teeth. What a perfect image of superhero discontent. It’s so great and yet so understated it goes by almost unnoticed. What’s the point of having superpowers, the image says, if you still have to brush your teeth? The acting coach says to the student “What did your character have for breakfast?” and here we see the exercise made literal. Raven’s life isn’t jetting about the world, mimicking people and getting into secret installations, it’s following Xavier around like a third wheel and brushing your teeth. This image is, for me, the essence of the X-Men appeal — the X-Men stand out in the superhero firmament because they all have incredible, world-changing powers but they’re all incredibly messed-up individuals, every single one of them. They could change the world, except they’re too neurotic to make it to the grocery store.

So Raven is concerned with her looks, which Xavier can’t understand, which is, of course, the other side of his expansiveness — he can’t understand why people need things he has in abundance.

The grown-up Erik Lehnsherr travels to Switzerland, like Jason Bourne, to find something. Bourne was looking for himself, but Erik is looking for Dr. Schmidt, the Nazi doctor who wasn’t really a Nazi doctor, who mentored him and developed his metal-manipulation powers during WWII.

Erik has gotten into the bank by pretending to be a client with a bar of Nazi gold. The screenplay doesn’t indicate where he got this bar of gold, but he does mention that “it’s all that’s left of my people.” Did Erik, under orders from Schmidt, extract this gold from the teeth of Jews in Schmidt’s prison camp, remove jewelry hidden on their persons? He doesn’t say, but we shortly see him do both those things to the Swiss banker who resists giving up Schmidt’s current location. Erik says he’d like to kill the banker, since the banker apparently has plenty of ex-Nazi clients, but he stops at merely removing one of his fillings. We will see later that Erik has no trouble killing Nazis, why does he demur at the opportunity to kill the banker? Perhaps he’s worried the murder of a banker would draw undue attention to him. In any case, the banker gives Erik Schmidt’s current location (Argentina, the ex-Nazi’s favorite hiding place).

Now, we meet a new character, Moira MacTaggert, a CIA agent in Las Vegas tracking the members of the Hellfire Club, an international consortium of gangsters, politicos, army officers and industrialists. And so another strain of early-60s political reality is brought to bear on the narrative: the CIA-Mafia-Vegas-Cuba mishegas. Moira is supposed to be looking for communists infiltrating the US. In real life, the communist infiltration of the US was, of course, nonexistent, a political Trojan Horse designed by conservatives to demonize liberals and create an “other,” much as — you guessed it — Hitler had done with Jews in WWII. So we see here that Moira is merely a gentler Nazi, rooting out conspiracies where none exist, until she stumbles upon a real conspiracy that goes far beyond political ideology. The Cold War, like The War on Drugs and the War on Terror, was a massively expensive lie, designed to make people afraid and keep the engines of commerce running. The US never set up concentration camps to imprison Communists, but only because mass murder was bad for business, and besides, we had nuclear weapons, mass murder was on the table from the beginning, it was the defining principle of the era.

Moira, like many female spies before her, sees an opportunity to use sex to do some of her own infiltration of the Hellfire Club. That instinct ties her to Raven, and in fact puts her ahead of Raven as far as this narrative is concerned, since Raven has only used her powers of transformation to hide her ugliness up to this point.

Now, we meet Emma Frost, “associate to Sebastian Shaw,” and apparently a high-ranking member of the Hellfire Club. Emma, as we can see from the above photo, is, like Moira, not above using sex to distract, in this case to distract one Col Hendry, a military guy doing business with the club. The fact that Emma is played by January Jones, Betty Draper herself, ties Emma to the early 1960s and helps her own disguise in the minds of the audience: it’s the Mad Men era, women don’t have power, they are merely decoration. Beauty, we see, is just another label to make someone “other” in this world, to make them less than human. Just as Raven pretends to be beautiful to fit in and Moira takes off her clothes to infiltrate, Emma uses her beauty to appear to be merely decorative. Moira, who knows nothing of any of this, scoots in behind as more decor. She dodges the advances of passing industrialists to try to get to Col Hendry’s private booth, not suspecting anything about Emma beyond her role as a procurer, and finds the booth empty.

Now look who’s here, it’s Sebastian Shaw, or rather, it’s Dr. Schmidt, seventeen years later and calling himself Sebastian Shaw, or perhaps he was never Dr. Schmidt any more than he was a Nazi. He no longer has a mustache, he no longer has reading glasses and he hasn’t aged a day, but we know it’s the same guy because he still enjoys Edith Piaf.

What does Sebastian Shaw want? At the moment, Shaw wants Col Hendry to use his power as a military guy to put nuclear missiles in Turkey, for as-yet-unknown reasons. Col Hendry, upstanding military guy as he is, politely refuses Shaw’s desire, and Shaw introduces a new character, Riptide, who, apparently, can create small localized tornados. Shaw, we see, has a talent for collecting mutants (the ultimate “other”) to his side for nefarious purposes, and he uses Riptide’s skills to terrorize Hendry, then reveals that Emma has her own skills, as a mentalist, a transformer (turning herself into diamond — even her clothes — unless she, like Raven, is always naked) and a super-powered whistler. Emma’s super-powered whistling calls in Azazel, who has the power of teleportation (and might be Nightcrawler’s father, depending). Hendry, faced with the sudden appearance of a bunch of mutants with mind-bending powers (and he doesn’t know the half of it) is flummoxed — this is not the meeting he was anticipating when he came to Las Vegas for a good time on the tab of the Hellfire Club. Meanwhile Moira, in her underwear, makes her way into Shaw’s hidden office and finds a stack of Russian documents on his desk, like a cub reporter stumbling onto a big story.

Next thing we know, we’re at the Pentagon’s War Room, or rather, we’re in Ken Adam’s set for Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove‘s war room, and we are reminded of the importance of design. Design, like smell, cuts to the heart of memory and brings with it a wealth of associations. To tie First Class to Dr. Strangelove is to obviate issues of taste – Dr. Strangelove was a blistering comedic attack on the Cold War, while it was happening. The issues raised were serious as a heart attack to its audience. It didn’t have mutants but it did raise the question of human evolution, Nazism and the repressed dream of a master race.

We’re at the War Room because that’s where CIA director McCone is, and he is, right now, talking to Moira on the phone about Col Hendry’s collusion with Shaw, who she thinks is a Russian agent. Moira, it seems, is pretty high-placed operative if she can get the attention of the Director while he’s in a meeting in the War Room, but McCone disregards her call — Col Hendry is right there in the War Room with him, transported by Azazel, talking about how he wants to put missiles in Turkey. Historically, of course, there would be no Moira MacTaggert in the CIA in 1962, that’s another fib told to us by the entertainment industry. The CIA didn’t have sexy young female operatives, that’s something that sprang from the world of James Bond, which First Class also consciously invokes in its historical-cultural mashup, even to the point of giving Erik Bond’s suit from Goldfinger.

Moira MacTaggert, temporarily a protagonist and looking for an expert on mutants, travels to Oxford to find Xavier, who has just received his degree. Meanwhile, Erik travels to Argentina to Find Dr. Schmidt, who he doesn’t yet know is really Sebastian Shaw. He comes to a bar that serves German beer and finds a couple of regular patrons who, as luck would have it, are pictured in a photograph up on the wall, with Schmidt, on a boat (a boat with anachronistic Trajan font on its stern). The tables have turned, Nazis are the Other now and these two pals of Schmidt are hiding in South America. Erik reveals himself and kills the two men and the German bartender. One of the men tries to defend himself with a Nazi knife (“Blood and Honor” it says on its blade) while the bartender approaches with a Luger, the Nazi pistol of choice. Even though Erik went in to get information about Schmidt, he got none from the men himself — he learned everything he needs to know from the boat photo with the anachronistic font. He kills two of the men in self-defense and one out of vengeance. Or, since he has control over all the metal objects in the room, he kills them all out of vengeance. The one with the knife gives the old Nazi excuse of “We were only following orders,” an expression that was hugely popular among escaped Nazis at the time: Adolf Eichmann had just been captured in Argentina and was tried in Jerusalem in the spring of 1962 and used the “only following orders” defense as his excuse. Eichmann had just been executed at the time this scene takes place, the knife-wielder’s use of the quote could not have been more germane, or more ill-timed to garner sympathy from Erik.

As at the top of the movie, a dramatic shift in tones as we switch from Erik and his steely, grim quest for vengeance, to Xavier, who seems to have everything. We meet him, drunk, having just given a presentation, with Raven hanging on him, obviously in love, and Moira come to learn about mutation. There’s a terrific beat where Xavier launches in on his “mutation is groovy” seduction spin and Moira cuts him off, wanting to focus on business. Before, Xavier’s expansive belief in the awesomeness of mutation was either academic or deployed toward the acquistion of sex (except in the case of Raven, who wants the sex but Charles won’t think of her that way, in spite of her being naked all the time). So, there is a man who loves mutation but only to get sex from “normal” women, not mutants, and he’s met by a sexy woman who doesn’t want sex but actually wants to talk about mutation, while Raven, a hideous mutant, glowers jealously in the corner. Xavier puts his fingers to his temple (apparently he can’t read someone’s mind without doing that) and sees Moira’s whole story, with Shaw and Emma and Riptide and Azazel and the whole schmeer. A challenge has been laid before him: move your theories out of the lecture hall and the barroom and into the real, and dangerous, world.

And look, here’s a chunk of that world now, as Shaw confabs with Col Hendry on that very boat in Miami. Miami, of course, was a key city during the Cold War, being America’s front porch to Cuba. It was the Miami mafia who, in real life, was conspiring with the CIA to kill Castro, and who, legend has it, then conspired to kill Kennedy. And here is Shaw in the middle of it with his team of mutants, with Col Hendry trying to extort money and peace of mind out of them. Shaw calls his bluff, revealing his own mutant superpower: he can absorb, hold, and release energy. That, it would seem, answers the question of “Why didn’t Erik just kill him?” and “Why hasn’t he aged?” Here, the Other have the Establishment Man cornered, on their own turf, as it were, and Shaw uses his power to kill Hendry. (What happens after that, I don’t know — certainly people will come looking for Hendry, not that they could really get to Shaw if they wanted to.)

While Shaw is killing Hendry, Xavier is at CIA headquarters at Langley to give a talk on mutation. Direcrot McCone has, apparently, given Moira another shot at proving herself. Again, I’m not sure why — operatives don’t generally get the ear of the director without a good deal more than a gut feeling — but here she is again, having brought Xavier in to back her up. McCone, for his part, lets us know where he found Moira — in the typing pool. It makes sense, but a jump from typist to operative is a huge one, even now, and I would imagine unheard of in 1962. No matter, the point of the scene is, again, in reflection of the previous, the Other and the Establishment. On Shaw’s boat, the Establishment tried to put its foot down on the Other’s turf and failed. Now, the Other has been invited into the inner sanctum of the Establishment (CIA headquarters! A meeting with the Director! And Raven, whose only qualification is “Xavier’s sister,” is there!) and, like Shaw, hands the Establishment its ass. Xavier reads everyone’s minds (including a high-ranking officer who is the father of William Stryker) and Raven shows her true colors. The Establishment reacts with horror — “They’re god-damned spies!” blurts McCone — but their horror is not of mutation but of, of course, Communism. At the back of the room is the guy who is always hanging around the corners of CIA offices, the guy who would later become the Smoking Man of the X-Files (although, in 2011, you couldn’t smoke in a movie, even one set in 1962), who sees opportunity in the weird. The Man in the Black Suit, which is what the movie calls him, is a prototype of the weird edge of 1960s intelligence, the kind of guy who would later chase after UFOs and employ men to stare at goats. First Class is stuffed to the gills with genuine history, which gives it a resonance that other superhero movies don’t.

Erik, tracking the man he knows as Dr. Schmidt to Miami, surfaces, James-Bond-in-Goldfinger style, in the harbor near Schmidt’s yacht, the one with the boat’s name in Trajan. He climbs aboard the yacht and finds Schmidt (who of course is actually Sebastian Shaw), lounging with Emma Frost and Riptide. Erik has brought a knife, the Nazi dagger he got from the “pig farmer” in Argentina. He is, of course, thinking of the right tool for the job of killing Schmidt — a Nazi dagger reading “Blood and Honor” on the blade, he feels, should carry the right moral heft. He’s wrong in this, and it will take him until the end of the movie to figure out the right tool to use to kill Schmidt.

To Erik, it looks like Schmidt is a callow jet-setter with a bimbo and a manservant, or perhaps a bisexual playboy, but surprise! all three are mutants. Erik gets the full brunt of Emma’s powers — the mind-reading (“He’s here to kill you” she divines, using only her psychic powers, and maybe the fact that Erik has snuck aboard in a black wetsuit and is brandishing a dagger), the diamond-skin, a sonic blast that incapacitates him and, apparently, some telekinetic powers — rather a lot of abilities for one mutant — that blast him overboard. Shaw adds a moral wrinkle to the scene, chastises Emma: “We don’t harm our own kind,” he says, perhaps forgetting about that time he killed Erik’s mother.

Coincidentally, the Coast Guard shows up.

Coincidentally, that is, in one sense, but not in another. Coincidence in that the Coast Guard just happens to catch up with Shaw at the exact moment that Erik does, but not coincidence because it is Xavier on the Coast Guard ship, in charge of the raid, which makes the scene the culmination of the act, bringing together our two leads in an epic “meet cute” for our love story to flourish. That’s what the whole arc of this first thirty-five minutes of the movie has been, just showing the paths our two protagonists take to meet each other. We met Erik in the prision camp contrasted with Xavier in his estate, then Erik hunting Nazis while Xavier picks off coeds, now we have Erik trying to get Shaw with a wetsuit and a knife, while Xavier has at his disposal the US Coast Guard.

Neither, we see, is a match for Shaw, who can block Xavier’s mind-reading powers with Emma’s own telepathy (somehow) and block the Coast Guard raiders with Riptide’s tornado-making powers, and escape in a submarine with the awesome power of A Lot of Money. (Erik tries a second tool on Shaw, his ship’s anchor chain, which also proves ineffective.) Erik tries to stop the getaway sub with his metal-controlling powers, but he’s not strong enough yet and Xavier must jump into the water to save him from drowning. ”I thought I was alone,” says Erik, and Xavier informs him “You’re not alone.” In its own way, it’s as romantic as “I wish I could quit you” or “You had me at hello.”

Act II begins and we move to The Man in the Black Suit’s Secret CIA Outpost, where apparently he has carte blancheto do anything he wants, including working with paranormal phenomena. The MiB says he’s developing these studies for purposes of military defense, to which Erik quickly adds “Or offense,” which is both a dig at the hypocrisy of the CIA (as though any weapon would be developed purely for defense) and a glimpse into the future schism between him and Xavier.

We now meet Hank McCoy, who is a researcher working for the MiB. He’s built a spyplane for the CIA, a reference to the U2, not the Irish band but the airplane, which, in 1960, was shot down over the Soviet Union, another key incident in the Cold War. Xavier “outs” Hank as a mutant, something the MiB didn’t even know. Hank is embarrassed — he’s been trying to keep his mutation a secret. ”You didn’t ask, so I didn’t tell,” he mumbles, another rare anachronism in this movie as he jumps thirty years in political references. The notion that Hank would be a mutant working for the CIA is, of course, a reference to the whole anti-communist fervor of the times, presented here as suspicion of homosexuality. In 1962, the only people who could be trusted, it was widely believed, was straight white men — anyone else might be a communist, or at least easily compromised and therefore suspicious as a communist dupe. InDr. Strangelove, Col Guano both equates and confuses communists and “preverts,” to a certain mindset of the time they were one and the same. There were, of course, many, many closeted gays working for spy organizations in the post-war era — who is better at keeping secrets, after all? — but to live openly would be to court death. (Ignoring, of course, that the director of the FBI, and who knows how many other highly-placed intelligence officials, were gay, this being a key approach of J. Edgar Hoover: make everyone so terrified of being discovered of being gay that they will never, ever ask if you are.)

So Hank, like Raven, has a mutation that makes him a monster, so he’s been hiding it all his life. ”If people knew, they’d hate me” is the reasoning here. Erik compares himself to Frankenstein’s monster in an earlier scene, and clearly that creature’s fate is what Hank and Raven expect to happen to them — villagers with pitchforks and a burning windmill. Hank, one could extrapolate, became brilliant and graduated from MIT at 15 so that people might not notice that he also has a mutation: hands as feet. But now, Hank sees that he’s among friends, specifically Raven, who, for the first time, sees a boy she likes who might like her back. Which is both romantic and a little sad, since, theoretically anyway, both Raven and Hank deserve to be loved by “normal” people, they shouldn’t need to date “within their race” if they don’t want to. In any case, since First Class can’t really go so far as to create a physical love story between Xavier and Erik, it instead offers one between Raven and Hank.

Oddly enough, the scene offers up another anachronism, this one cinematic: Raven goes to the upside-down Hank and looks ready to kiss him in a visual quote from 2002′s Spider-Man, the movie that launched the “Marvel Movie” brand in the first place. ”You’re amazing,” gushes Raven, in case we didn’t get the reference.

Meanwhile, in Sebastian Shaw’s swanky, swingin’, Bond-villain-style submarine, Shaw and Emma watch a news report on the American missiles in Turkey. The placement of missiles in the Cold War was a real thing, for those too young to know, and was largely where the battles of the Cold War were fought. The world was the chessboard of the superpowers in the early 1960s, and the thing that was keeping us all alive was a doctrine called MAD, which stood for “Mutually Assured Destruction.” That is, the only thing that kept us from destroying another country’s cities was the assurance that our cities, too, would be destroyed. It created all the tension of war, and the economic boom of war, without having to deal with battlefields or bloodshed. The battles were fought in people’s minds, which makes the early 1960s the perfect place for someone like Xavier to fight — who better to manipulate the minds of the populace?

Shaw, of course, understands this, and he has had “the Russians” (the KGB?) design for him a spiffy helmet that, somehow, will block a telepath’s attempts to read his mind. Ordinarily, this would make Shaw a genuine tinfoil-hat conspiracy nut, but in this case the helmet serves its purpose. To compensate for the helmet looking kind of ridiculous, he acts like a jerk to Emma, suddenly becoming Don Draper to her Betsy, telling her to fetch some ice for his drink. Even at the frontiers of human experience, it seems, the old biases still thrive.

While Shaw is at the North Pole in his submarine, preparing to destroy the world or something, Raven and Hank waste no time in getting to know each other. They bond over their shared desires to appear “normal.” The 1960s are still young, and the postwar conservativism that affected the US, despite the election of Kennedy in 1960, is still very much the order of the day. Perhaps the hippies of San Francisco would accept a boy with hands for feet or a scaly blue young woman, or perhaps they would be accepted at Harvard, where Timothy Leary was beginning his experiments with LSD. (Both Raven and Emma wear miniskirts even though they would not be invented until 1964. Mutants, as always, lead the way in evolution.)

Hank, we learn, has developed a serum that, he believes, will help a mutant maintain his or her abilities while making them appear “normal.” (How this is supposed to work, I have no idea — that’s right, I doubt the veracity of the science of X-Men.) Raven can’t wait to be jabbed by Hank’s needle, so to speak, but Erik comes along to pour cold water on their romantic-scientific tryst. Not only is Erik older and sexier than Hank, he’s prouder and more persuasive than Xavier. When he tells Raven “I wouldn’t change a thing,” it carries more weight than when Xavier says “Mutant and proud,” because Erik has been through the worst a mutant, an Other, can be put through, and come out the other side, while Xavier has never had to suffer a day in his life. Thus, he turns Raven’s head as her one-on-one with Hank suddenly becomes a triangle.

Erik, for his part, just wants to grab the CIA file on Shaw (which is left sitting around in someone’s office) and get back to his vengeful manhunt. Xavier holds him back, offers him something more than vengeance. He offers him, essentially, a family, which he lost to Shaw, and a community — a place at the table. That is, of course, the thing that Xavier’s position of privilege can offer the rage-filled loner Erik, although Erik is obviously loathe to accept Xavier’s charity. The basement-dweller can only see the garden, the attic-dweller can see the whole block. Erik and Xavier are both Other, but from different ends of the spectrum: Xavier defines himself by his expansiveness while Erik defines himself by his solitude. That bar of Nazi Gold, remember, that lump of metal, was “all that’s left of my people,” Erik said, not understanding that he might belong to another Other.

Speaking of Xavier’s expansiveness, we soon see that it not only knows no bounds, it seeks to expand the bounds it doesn’t have, as the MiB shows Xavier the prototype of Cerebro, a machine designed (by Hank, the Lucius Fox of the team) to help Charles expand his mind, literally, not just in the Timothy-Leary sense. Erik announces that he’ll help Xavier find Shaw his way (with lots of lingering close-ups between them) as long as it’s just mutants, no CIA agents doing the hunting. The MiB, with no alternative, agrees: the Other, only two strong, is already wresting control from the Establishment, and it’s only 1962.

But immediately, all is not well between Xavier and Erik. Erik resents Hank, not just because Hank is ashamed of his Otherness, but because Hank literally controls the machinery. Erik, of course, could easily dismantle Hank’s machinery with a flick of his wrist, but he’s now beholden (and falling in love with) Xavier. ”You look like a lab rat,” he sneers to Xavier as Hank hooks him up to Cerebro (Hank explains to Xavier how the machine works, even though I would imagine it’s unnecessary to explain anything to Xavier). Erik, of course, has been a lab rat, and he resents the notion of Xavier, himself or any mutant working in the service of anyone, even the CIA, even in the service of capturing dangerous criminals and defusing an international crisis.

Erik and Xavier, two straight men in 1962, have fallen in love. Like all straight men who fall in love, they must find things to do together in order to have an excuse to hang out. The manlier the better. Hence, the first thing they do after deciding to work together to find Shaw is to go to a strip club and indulge in some very groovy Mad Men style sexist shenanigans. The joke here being, of course, that they’re not looking for sex but for mutants, in this case a winged young lady named Angel Salvador. Still, the message is clear: like James Bond, Erik and Xavier have found that saving the world doesn’t have to mean you can swing a little. Next, they find a young black cabbie in NYC named Armando Munoz, a imprisoned young man named Alex Summers, an awkward youth with a hyper-sonic voice named Sean Cassidy (not Shaun Cassidy), and, briefly, a taciturn guy named Logan, who, in the movie’s single funniest moment, politely rebuffs their advances. Even Erik and Xavier strike out sometimes, and not everyone wants to join a family.

The team that they assemble are all variations on the Other — a stripper, a black youth, a prisoner, an awkward, rejected teen boy, they’re like the cast of a Bob Dylan song come to life. We’re watching the 1960s come together. Logan, of course, had his ’60s a hundred years earlier, this is not his movement. (I also note that Armando, while black, is not black and angry, just a working-class dude driving a cab, which makes him “other” enough in 1962 New York, no reason to disenfranchise him as well, or make him a stereotype.)

Meanwhile, in the Arctic, Shaw and Emma and Azazel luxuriate in Shaw’s swanky submarine. Shaw tans himself in the sub’s nuclear reactor while Emma and Azazel try to figure out where Xavier is — they know someone is onto them. Nuclear submarines were brand new at that time: the Thresher had just been launched a year prior to the events of First Class, and would tragically sink a year later. The exposition in the submarine scenes is perfunctory, but what counts is the attitude: Shaw, Emma, Azazel and Riptide are crewing a submarine while dressed for yachting. Bond villains always dress well but have crowds of soldiers working for them; Shaw keeps his crew small, efficient and stylish.

In case the viewer felt that the movie didn’t have enough references to early 1960s politics, Erik and Xavier go to Washington DC to lounge on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, where Dr. Martin Luther King would, a year hence, launch the Civil Rights Movement, yet another plot to normalize the Other in the US. Xavier, ever the idealistic 1960s liberal, expounds to Erik about how he “feels” the mutants out there, feels their pain and isolation, wants to help them, knows he can help them. He looks like he’s ready to form the Peace Corps. This kind of idea would have had no traction under Eisenhower, it took Kennedy and Camelot for Americans to see themselves as pacific leaders taking the world into the 21st century. Erik, who has seen Otherness from the other end of the telescope, knows the flip side of Xavier’s dreaming: raising up the Other may seem like a good idea, but that idea exists for the purpose of making the liberal feel good about himself, not for the benefit of the Other. The downside of raising someone up is that they are made a target, in Dr. King’s case, quite literally, and postwar US history is filled with disasters undertaken out of kindness.

It’s this kind of density, this kind of examination of theme, not just in metaphors but in concrete historical reality, that makes First Class the best of the X-Men movies by far. The earlier movies discussed Otherness in wide-ranging, crazy-quilt ways and were set in a vaguely-defined future. You could find yourself in the X-Men universe but you couldn’t feel the grit of it. Here, the characters exist in an all-too-real, identifiable context.

Back at the ranch, or rather the MiB HQ, Raven bonds with the other X-Men kids by announcing her new identity: Mystique. Ever the front-runner, her choice of name predate’s Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique by a year. The Feminine Mystique, it’s worth noting, was the first book that identified a widespread problem in the US: women — white, middle-class women anyway, the Betty Draper’s of the world — were becoming bored and unhappy with their parochial, dead-end lives. The actual phrase, “the feminine mystique,” was a term Friedan coined to describe the “ideal woman” that had been created by the Don Drapers of Madison Avenue: beautiful, stylish, poised, subservient and utterly vacant. Real women, Friedan insisted, want something more than a husband and kids and postwar affluence. Raven, who lives her entire life in the disguise of a beautiful, poised, subservient woman, feels this tension acutely — it’s no mistake that she becomes Mystique.

Armando, for his part, becomes “Darwin,” for his ability to adapt and survive. Aha — that’s why he’s shown driving a cab rather than storming the gates of the white establishment: he’s not a rabble-rouser, he’s an adaptor. He will do whatever works to ensure his survival. (The truly freaky Darwin, who can grow gills at a moment’s notice and who knows what else, is a character largely new to this movie, I’m guessing he was included so that there would be a black character — any black character — placed in the context of the early 1960s. Sean becomes Banshee, after a character in Irish folklore: oddly, a female character, who’s wail signals an imminent death, an odd mixture of feminine and tough for a young Irishman. The mixed-race Angel (an Other twofer), appropriately, has two talents: in addition to her dragonfly wings, can also spit fireballs. Alex, the troubled youth of the bunch, can sling laser-hoops out of his body, and becomes Havoc. The tone of the scene, set to the slinky groove of “Green Onions,” is youthful energy. These kids aren’t angry, they’re overjoyed to have found each other, and we’re reminded that the youth movement of the 1960s sprang not from a hippie conspiracy but a statistical fact: the Baby Boomers didn’t ask to all be born at once, it just happened that way, but as the 1950s gave way to the 1960s, “youth” became a “problem” for politicians to solve. Youth, in fact, became its own Other, and the scene at MiB HQ, with the symbolic destruction of the statue of the MiB himself, shows a rebellion movement born of joy and self-realization.

The joyous gathering of the new X-men recruits, in the inner sanctum of the MiB HQ, echoes what was happening in college campuses all over the world. It begins with young people discovering themselves, claiming their powers, forging new identities and enjoying their commonality and diversity, and ends with one of them destroying the Establishment leader in effigy. I was struck by the moment of Havok slicing and burning the statue of the MiB (odd that he has a statue of himself on his compound) and trying to remember what it reminded me of. Then I realized, of course, it reminds me of campus protests, where all sorts of unspeakable acts are visited upon the statues of the Great White Men who built the temples of learning but whose relavence had long since vanished. The young recruits are the campus youth movement, the Other gathered in an establishment sanctuary, free from the worries of employment (stripper, cabbie), freed from imprisonment, free to concentrate on “finding themselves,” and, thus, free to concentrate on the next thing. The next thing, in college campuses, is supposed to be “studying,” and here in X-Universe is supposed to be “finding Shaw,” but the end result in both cases is the same: “saving the world.” That’s what the 1960s youth movement, the Hippie Dream, was all about, although, like with the X-Men recruits, “toppling the Establishment” (or at least thumbing one’s nose at it) is the first step in defining themselves. The reason Bob Dylan became the “voice of his generation” was not his politics, it was his refusal to be identified, to be pinned: “Whatever you say I am, that is what I am not.” That strikes at the core of the appeal of X-Men from the beginning, and First Class is not just a history lesson, but an X-Men history lesson. Other movies pay homage (or lip service) to their comics origins, First Classactually puts its comics in historical context and thus illuminates their genuine cultural import.

Back at CIA headquarters, Moira gets a pat on the back from Director McCone. In an ahistoric moment of clarity, McCone decides it’s perfectly reasonable to send a bunch of super-powered mutants to go solve an international crisis. When Stryker splutters at the enormity of this harebrained scheme, the MiB says “these ‘freaks’ are dedicated, hardworking [looks for word] people.” ”Patriots” is what we’re expecting him to say, but they’re not patriots, they can’t be, some of them aren’t even Americans, and besides, patriots are boring, Captain America is a patriot and he’s a dim-witted tool of the patriarchy compared to the hip youngsters of X-Men, nothing could be less hip in 1962 than to be a “patriot.” (Also, the MiB probably wouldn’t call them “dedicated and hard-working” if he had seen their statue-destroying rap session.)

And sure enough, the “grown ups” come back from their Establishment meeting to find their recruits in the midst of an Animal House-level dorm party. (Animal House, it should be noted, is also set in 1962, as was its dramatic precursor American Graffitti. 1962 here indicating “the last year of America’s innocence,” as though a nation embroiled in racial tensions, H-bomb tests, global conflict and systematic oppression of women could be considered “innocent.”) Moira, the woman who took off her clothes at a moment’s notice in Las Vegas, is shocked and dismayed at the recruits’ behavior, while Erik and Xavier are embarrassed. Mystique, on the spot and unshamed, feeling the power of her new identity, renames them “Professor X” and “Magneto.” The hip kids, the Boomers, want the grown-ups to take part in the fun, but the grown-ups aren’t biting. Lest we forget, Don Draper was baffled by the Rolling Stones and James Bond hated the Beatles — even the hippest adults of the WWII generation didn’t “get” the youth movement. Xavier’s disappointment in his “sister” Mystique shows the moment where the patriarchy, even the supposed liberal patriarchy, lost touch with its better half, and with its children — the beginning of the Generation Gap.

Erik and Xavier, perhaps to solidify their status as WWII-generation “good guys,” undertake a Where Eagles Dare – style undercover mission in Russia. They come to a checkpoint in the middle of a very Inglourious Basterds kind of wood, and Xavier uses mind control to get him and his team past enemy lines. I considered for a moment that this might be an act break, since Erik and Xavier are no longer “getting to know one another” and are instead acting upon Shaw, but “acting upon Shaw” isn’t really the thrust of their arc, it’s still “falling in love.” As before, when they went to a strip club to recruit Angel, they’re still doing “guy stuff” together, to cement their friendship. What could be more macho than dressing up like working-class laborers and getting in a truck with a bunch of soldiers on a recon mission in enemy territory? (Moira has also come along, just so, you know, things don’t get too gay.)

Xavier, Erik and Moira spy on Emma, who has come in Shaw’s place to meet with a Russian general. Moira, absent Shaw, wants to call off the mission, but Erik, not yet Magneto, but certainly not a team player, charges ahead. He was embarrassed by Mystique’s behavior back at the MiB HQ, but here, in the midst of the Establishment, he chafes at orders and regulations — he’s caught in the middle.

Emma seduces the Russian general (whose name, according to the credits, is “Russian General,” appropriately enough, since the role is sort of a “general Russian”) while Erik does his metal-manipulation thing to get the guards out of the way. Erik’s rash action propels Xavier into action (and underlines McCone’s flunky’s worries about untrained freaks being let loose into international crises), making him a kind of psychic mop-up crew in Erik’s path of destruction. The two of them corner Emma in a pretend sex-scene with the general, which they then turn into a much more provocative pretend sex-scene by binding Emma against the footboard of the general’s bed. It’s always thus with bromances — strip clubs, playing army, tying women up, everything but the task at hand.

Xavier reads Emma’s mind and learns Shaw’s plan: start WWIII, kill billions of humans, have mutants take over the world with the Hellfire club as the dominant political party and Shaw as world dictator. Shaw’s plan is remarkably similar to Blofeld’s in You Only Live Twice, with the remarkable exception that Shaw’s plan actually makes more sense.

This, the mid-movie point, represents a consummation for Erik and Xavier. The fact that it is the most explicitly sexual moment in the narrative, with Erik tying up Emma while Xavier pillages her mind, only underlines its true nature, to show the romance of Erik and Xavier in bloom.

While Erik and Xavier, er, “have their way” with Emma in Russia, Shaw and his team make their move on MiB HQ. Shaw is striking back at Xavier for poking around with Cerebro (the shots of Xavier with his head in Cerebro, ecstatic and lit from within, tie him to 60s mind-expansion gurus like Timothy Leary and John C. Lilly). First they kill all the humans, then they come for the mutants. You can come with me and be free, Shaw says, or stay here and live in slavery, and the camera points to Darwin, because, you know, slavery. In the scheme of First Class, this is like the Students for a Democratic Society (which formed in — you guessed — 1962) crashing the peace-and-love party. Shaw, of course, is no student, he’s been around forever, he’s more like an outside agitator, a warmonger disguised as one of the hip kids, fomenting rebellion because, well, that’s the business he’s in. ”You can join me and live like kings and queens,” he says, looking at Angel, but we’ve seen how Shaw treats Emma — there will be no equality in Shaw’s version of the future. Angel, she of low self-esteem (she is a stripper, after all) comes with Shaw, but Darwin and Havok try to stop her. Darwin, sadly, goes from being the non-stereotypical black guy to being the stereotypical black-guy-in-the-movies, and becomes the Noble Sacrifice to the cause, the first one to die in the fight against evil.

Shaw then travels to Moscow to persuade the Russian general to put nuclear missiles in Cuba, as an answer scene to the one where he persuaded Col Hendry to put missiles in Turkey. The placement of nuclear missiles in Turkey and Cuba, for those not up on their Cold War history, was a very real concern at the time, and seemed like madness to sane people. For a movie in 2011 to suggest that it was not madmen but power-hungry mutants who arranged for the missiles to be placed thus doesn’t even stretch the truth that much. ”We are the children of the atom,” says Shaw at one point, and we all were in 1962 — the Bomb’s awesome power drove everyone — world leaders especially — a particular brand of insane.

Erik and Xavier come back from their own Russian sojurn to find MiB HQ wrecked and Darwin dead. Erik and Xavier, so recently getting along so well, now begin to split apart. Xavier wants the kids to go home, Erik wants to fire them up to avenge Darwin. (That would make Darwin the Agent Coulson of First Class.) Xavier splits the difference in their approaches — he will train the recruits, but do it at home, his home.

Meanwhile, back at CIA HQ, McCone (who was a real guy) and Stryker (who was not) have Emma in custody, in a room, and in a costume, designed to remind the viewer of the most famous scene in Basic Instinct, to tie that dangerous blonde to this one. (Catherine Trammel, the character Sharon Stone played in Instinct, was an inversion of the Hitchcock Blonde, the unapproachable ice queen. Catherine was blonde but also provocative, aggressive and wantonly sexual. Emma is, on the other hand, much closer to the Hitchcock ideal, especially as played by January Jones: remote, chilly and disdainful of desire.) McCone, being a straight arrow, wants to “turn Emma over” (to whom?), while Stryker wants to throw out the law. ”There’s a war coming,” he says, and it’s better to give up liberties for security. That, of course, ties Stryker to not only Dick Cheney, but to warmongers like Robert McNamara, who pressed the case for the war in Vietnam when he knew it was unnecessary, wasteful and tragic. By making it Stryker who pushes for totalitarianism instead of McCone, it also places one more X-Men character into world history: the real-life director of the CIA, the screenplay asserts, would never hold a US citizen without due process, it would take a comic-book character to do something that crazy. There’s a war on, “but with whom?” asks McCone, as well he should: the Cold War was as much about going toe-to-toe with the Soviets as it was about America’s war on its own people, its own Other.

In the War Room, the assembled brass, led by the Secretary of State (the screenplay does not identify him as Dean Rusk, so there is no reason to suspect that Dean Rusk ever had to deal with a mutant conspiracy to destroy the world) agrees to blockade Cuba in order to prevent the Soviets from putting missiles there. This, too, more or less lines up with historical fact. That this vote takes place in Dr. Strangelove‘s War Room gives it only the slightest spin into fiction. In a similar room in the Kremlin, the Russian general holds a vote for his own entry into war.

In between the two dark rooms of power, Xavier welcomes his charges, his kids, under sunlight, open spaces and fresh air, to his home. While the Establishment votes to make war, Xavier, from his position as benefactor, extends a hand of generosity. He places his team into training, giving them each the tools they need to develop their skills. For Erik, skill is not the problem, but redirecting his anger is. Erik believes he’s only effective when out of control, but Xavier, a control freak if there ever was one, pushes Erik to build his talent without anger. Xavier is an idealist, after all, because it’s easy for a hugely wealthy young man to be an idealist, but Erik is a pragmatist: he doesn’t want to save the world, he wants only revenge. Xavier is process oriented, Erik is result-oriented. What’s more, Erik rankles at the very notion that he is there to “learn” from Xavier. He might be his lover, but he won’t be his student. Rather the opposite: as far as Erik is concerned, it’s Xavier who has some things to learn about the harshness of the world. He may be an inspiring teacher, but he’s also a condescending pedant, absolutely sure of his rightness. Like Shaw, he wants to help mutants, to give them their freedom and raise them up. And, like Shaw, the underlying presumption is that his way is the only way to be right. Erik, on the other hand, strikes a more libertarian bent. He, too, wants mutants to be free, but he doesn’t want them to follow any rules at all, he wants them to think for themselves and make their own decisions. He goes to Mystique to press his point, making her heart the battleground between him and Xavier.

Meanwhile, Beast and Mystique’s budding relationship flourishes as Beast finally analyzes the blood he took from her a few reels back. Mystique’s blood, it seems, is unique, it will keep her looking like a teenager when she is middle-aged. That’s a kind of grim news for someone whose whole problem is her appearance, but she sits on Hank’s lap to look in his microscope, simultaneously feeding his desire to be taken seriously as a geek, and teasing his Beast nature out of him.

At the end of the long, eventful “training montage,” Xavier challenges Erik to move a gigantic radar dish. I don’t know whose radar dish it is or how they feel about Xavier and his freaks monkeying around with it, but Erik initially fails to move it. Xavier, for the first time, asks permission to read Erik’s mind, a marker of how far they’ve come in their relationship. Xavier, who has used mind-control indiscriminately throughout the movie so far, now grants Erik his mental privacy. A curious inversion, when the romantic partner grants his lover less intimacy. He dredges up a memory of Erik with his mother, a memory of intense love and tenderness, and tells him that his good memories can outweigh his bad ones if he allows them to, and make him more powerful. Love, he’s saying, is stronger than anger, which was, of course, the revolutionary idea of the 1960s. Erik’s tragedy, like Bruce Wayne’s, is his ultimate inabilty to let go of the past. His trauma is his self-identity. But for now, Xavier has shown him the way to enlightenment, and he is visibly moved.

They look as though they are about to kiss when Moira leans out the window and announces that Kennedy has launched what we know today as the Cuban Missile Crisis. Then as now, nuclear war is the ultimate romance-killer.

As the fantastic merges with the historic, no less a personage than John F. Kennedy is brought in lend weight to plot of X:Men: First Class. The footage is real, as is the footage that follows, of stores being sold out of canned goods and people stockpiling fallout shelters. Fallout shelters were big news at the time. The Twilight Zone had featured an episode about a fallout shelter a year earlier than the Cuban Missile Crisis; Bob Dylan, in February 1962, recorded a song about them, “Let Me Die in My Footsteps.” What seems quaint now, the idea that one could run and hide from a nuclear war, was, unbelievably, very real and present to the general populace. I myself was a mere tadpole in October of 1962, but my parents assured me, yes, for a few days, you pretty much just didn’t know if the world was suddenly going to end. In its way, it’s a comforting thought, that this level of madness was brought on by fantastical mutants bent on world domination, as the reality of the situation is too mind-bending to absorb.

In practical terms for the adventure narrative of First Class, the Cuban Missile Crisis is a clue for our protagonists to find Shaw. Remember, “to save the world” is not their goal, only “to find Shaw.” Xavier to stop him (to make the world a better place), Erik for his private, personal revenge. Xavier is high-minded, Erik is low-minded. Xavier may be who we want to be, but Erik is who we are.

In his submarine cruising beneath the Russian ship carrying the missiles to Cuba, Shaw has drinks with Angel and gloats about his imminent victory over the humans. Shaw is like one of the “Masters of War” Dylan sang about, the man who has no loyalty but to his own bottom line, the man who longs for war because it’s in his interest. And power, as Henry Kissinger once said, is the ultimate aphrodisiac, as we see Angel snuggling up to Shaw in Emma’s absence. Shaw’s treachery may wipe out the human race, but that’s an abstract concern — what the viewer registers is that he was once snuggly with Emma, now he’s snuggly with Angel — he has no loyalty whatsoever. (It’s kind of hard to see at this point what a winged woman really brings to a party involving nuclear missiles and mass death, but I guess she could come in handy somehow.)

In contrast to Shaw’s sleazy romantic opportunism, back at Xavier’s ranch Mystique and Beast (who Mystique still calls “Hank”) re-connect about the appearance-altering serum Hank has developed. Hank can’t wait to take it, to “look normal,” but Mystique hesitates. What’s happening, on a subtexual level, is a discussion of the notion of “passing” — if one can “pass” as normal, should one? This, too, was a key issue of 1962, as minorities were entering domains formerly held exclusively by whites. Was it better, at the time, to pretend to be something you’re not, in order to raise your stature? Or was it better to stand out from the Establishment and assert your right to be Other and demand parity? Hank is convinced he must appear to be “normal” (how the serum will let him keep his big feet while making him appear to be “normal” is a different question), but Mystique, infected by Erik’s fervent militarism, isn’t so sure she wants to be “normal” any more.

While Hank and Mystique sort that out, Xavier and Charles retire to the drawing room for some chess and some argument. (Chess, I realize, has been Xavier’s and Erik’s game of choice for a long time, but it’s worth noting that chess was also, in 1962, a hugely popular international sport, covered by the media the way we now cover tennis or soccer, precisely because of the Cold War — the Russians, for various reasons, had been the World Chess Champions since 1948, and chess championships became a political hot button and high international drama. Small wonder a chess game figures prominently in 1963′s From Russia With Love.) The conflict buried in their friendship is now brought to the surface: Xavier wants to show the world how wonderful it is to be a mutant, and Erik knows that to expose himself as Other is to mark himself for extinction. (Funny how Mystique changed her mind about Hank’s serum because she was inspired by Erik, yet here’s Erik saying that the safer thing would be to not draw attention to themselves.) The scene is a kind of Yalta conference, with Xavier and Erik deciding how to deal with the world once peace has been struck. In this regard, you could say that nuclear weapons were the superpowers mutant superpowers — you have to use them, or else people will try to kill you just for having them.

Back at the lab, Hank takes the plunge and injects himself with his serum. Like all self-made serums in every fantasy, it has unintended effects. Not only does it “bring out the beast” in Hank, but — holy exchange of bodily fluids! — Mystique’s blood makes Hank blue as well. Blue, without the ability to change back.

Mystique, having broken with Hank but not aware that Erik’s chain of thought has run to a different place, goes to Erik and tries to seduce him. Erik turns her down, leading to the movie’s second-funniest joke, where Mystique turns from Jennifer Lawrence to Rebecca Romijn. Erik accepts her desire but pushes her inner conflict to a place where she can no longer hide. To live openly, honestly, he says, she must appear as she truly is. She is thinking about beauty, and luck with boys, but Erik is talking about — surprise — world domination. The Cuban Missile Crisis, for Erik, is an all-or-nothing gambit — either he perishes in his quest for vengeance, or he, like Shaw, becomes the leader of a new dominant class of people, there is no alternative. He can’t save the world without drawing homicidal intent toward himself, if people know that he’s stopped WWIII, they will know his Otherness.

Mystique, now emboldened, ditches her clothes and goes to find Xavier, in the kitchen, in the same kitchen where they met years earlier. She’s there to tell him off, like the subject of The Feminine Mystique, to tell the condescending white male patriarch that his ideas are outmoded and constricting, that his notions of freedom are really just another kind of slavery if it means muting one’s voice in order to “get along” with the Establishment. Xavier knows that change is coming, but he wants to meet it halfway; Mystique has been radicalized.

The most striking, most unusual feature of the screeplay for X-Men: First Class is that it does not have a traditional end-of-second-act low point. In the typical superhero narrative, the story is: villain appears, superhero fights, villain triumphs, superhero comes back from defeat. That doesn’t happen here, because First Class, lest we forget, is a romance. The romantic comedy goes: boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl back, but a straight romance doesn’t need a happy ending, and in fact can have a tragic ending, as in Romeo and Juliet or The Fly. In the romantic tragedy, the two leads want to be together but cannot — the forces arrayed against their union are too great. The forces arrayed against Erik and Xavier are all internal, and deal with their past and upbringing, irreconcilable questions of identity and personality. Erik cannot wake up in the morning and no longer be a persecuted Jew, and Xavier, for all his psychic power, cannot imagine life in Erik’s shoes, because he’s always had everything he needs. If they could change, if they could reconcile their differences (that’s why the movie spent the first act underlining those differences), they could stay together and save the world, but the narrative drives them irrevocably toward breakup and tragedy.

So what is the structure of First Class? I would say it’s: Act I, Erik and Xavier head on a path toward each other with Shaw as their common enemy, culminating in their meeting; Act II, Erik and Xavier pursue Shaw together and fall in love through the action of doing so, culminating in the raid on the Russian general’s house; Act III, a retreat to more internal matters as Xavier attempts to temper Erik’s anger with love while he trains his recruits; and Act IV, where Erik’s and Xavier’s relationship is put to the test: can they work together, save the world and be happy, or will the polar opposites of their pasts hinder their efforts and tear them apart, simultaneously bringing the end of the world? (“The end of the world” is an overused trope in superhero narratives — hell, a lot of narratives — but when it’s tied to a love story it become elevated; a romantic breakup often does feel like the end of the world, First Class merely literalizes it.)

So, as we move into Act IV, our team, our shaky team of ill-fitting misfits, whose agendas are disparate and whose various romantic entanglements are unsettled, “suit up,” put on their uniforms, their uniforms that declare their Otherness (the last thing Erik, a Holocaust-era Jew, could possibly want to do at this point), and head into battle. Hank has provided them with an airplane, a Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird to be precise, a plane that wouldn’t fly for another two years but hey, we expect Hank to have access to toys ahead of time. Hank has also, to his chagrin, turned into Beast. Mystique, for her part, likes the new Hank — what woman would prefer a shy, awkward geek to a brainy beast?

In the waters outside Cuba, Russian and US ships head toward one another at the “embargo line.” Neither the Russian or American commanders want conflict, which is, truth be told, the position of any soldier. Soldiers are always sent into battle to kill each other over things decided upon by politicians in dark rooms thousands of miles away, and the tension of the standoff scenes of First Class, like the rest of the narrative, view the soldiers discomfort through the lens of fantasy: it’s one thing to dread combat because some soft-bottomed politician wants it, it’s something else to dread it because a deranged mutant no one has even seen wants it. Shaw’s mutation, don’t forget, is “absorption of power,” it’s central to his personality that he should gravitate to a situation where he cannot lose: even a nuclear blast would only serve to strengthen him.

The Russian ship carrying the bombs to Cuba has been taken over by Azazel, who ignores orders from the Soviet HQ (someone high-level has come to his senses) to return to port. Xavier, taking matters into his own hands (or head, anyway) hijacks a Russian officer and has him fire upon his own ship, destroying the nukes. Good going, Xavier! You just turned that Russian officer into a war criminal and a traitor!

This, of cours, is where history and First Class diverge. There was no mysterious blowing-up of any Soviet cargo ship, there was no battle at all (not that day, anyway, and I should know — it was my first birthday!), and the remainder of the narrative moves forward on a fantastical action-adventure template.

Shaw, his party spoiled, moves to his “back-up plan,” which involves soaking up energy from his nuclear reactor. In this way he communes with the god of the age, the mysterious atom that held such sway over the world in those dark days; a nuclear reactor is like his Ark of the Covenant. (Like a lot of back-up plans, this one isn’t very good: Shaw never gets around to explaining what he’s going to do with his nuclear-powered body once he gets it.) Xavier, acting as a kind of wireless relay, sends Banshee to find Shaw’s submarine and cheers Erik on to lift it out of the water. ”Remember, the point between rage and serenity” is the thought he places in Erik’s mind, ever the bossypants, as he struggles to control Erik in the only way he can. ”Lift that sub,” he’s saying, “but do it my way.” Erik, for his part, is willing to surrender to Xavier’s control, and we can see in his face the conflict of emotions. He does love Xavier, he loves his power and his ability to control, but his identity, his pride, won’t let him surrender.

As Erik raises the submarine (no entendre there), Riptide counters with a tornado, Erik drops the submarine on a beach, the X-jet crashes. Miraculously, everyone, even normal-human-being Moira, is perfectly okay. (How Shaw managed to keep a grip on his nuclear reactor as his submarine flew, crashed, broke apart and rolled over is not explained.)

Various folks fight: Beast and Azazel, Havok and Angel, Banshee and Angel, Erik and Riptide, Mystique and Beast and Azazel, so forth. Events move too quickly for the viewer to ask the typical X-Men narrative question, the one that begins “Why don’t they just…?” Xavier does what he can with mind control, although he can apparently only concentrate on one mind at a time, in this case Erik’s, as he guides him toward Shaw. That is, he guides Erik towards his goal of revenge, knowing that it is bad for Erik’s soul, and not realizing the extent to which it will ruin their love.

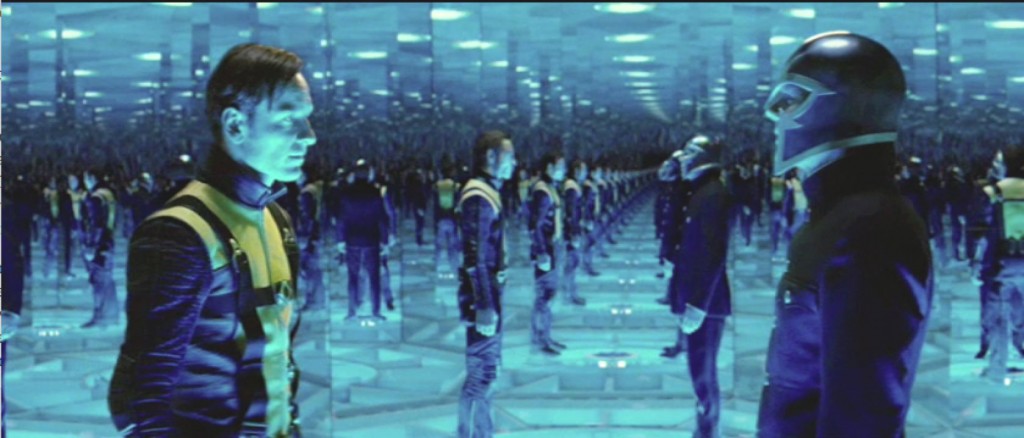

Erik finds Shaw in a literal hall of mirrors at the heart of the submarine, and learns that Shaw cannot be beaten with physical force. Shaw, the silver-tongued devil, tries to tempt Erik to the dark side (maybe that’s why the helmet, to look more like Darth Vader). He apologizes for “everything that happened in the camps,” something that his historical counterpart, Eichmann, could not bring himself to do, then explains that it was all for his own good, exactly like an abusive father. Shaw is, really, Erik’s abusive father, and everyone knows how the Abusive Father narrative ends: the son destroys him but inherits his poison. He removes Shaw’s anti-mind-control helmet and puts it on himself, his decisive moment: he loves Xavier, but he will not be controlled, by anyone. Xavier’s and Erik’s breakup, like their meeting and their consummation, are handled through an intermediary — Xavier must watch, through Shaw’s eyes, as Erik betrays everything Xavier has wanted for him. Erik has remembered, he’s had the perfect weapon to kill Shaw all along: that coin that Shaw gave him in payment for his mother’s death. Erik still has the coin, and is now ready to pay it back, and he sends it through the head of the immobilized Shaw. The great irony is that he needs Xavier’s cooperation to pull off this stunt, it’s the only way he could do it. And so Xavier must watch helpless as Erik not only murders Shaw but any chance of happiness with Xavier. He, in fact, makes Xavier an unwilling accomplice to his murder, his revenge, forces him to become the thing he said he would never be, the thing he has always blithely assumed he’d never have to be: an ambassador for vengeance. Xavier, in this moment, is also helpless: he can’t release Shaw from his mental grip, that would allow Shaw to kill Erik, the man he loves. His agony in the moment Erik’s chilling revenge is palpable: he’s not only seeing Erik turn evil, he’s experiencing Shaw’s death — in slow motion.

Back in Washington, Stryker (remember him?), the Cuban Missile Crisis over, suggests destroying the island where all the mutants have congregated, exactly as Erik has feared the Establishment would. (Stryker’s panic over the possible Mutant Takeover was sparked, the viewer will recall, by Mystique’s impersonation of him.) McCone, bless his heart, disagrees with Stryker, but only because there’s a human — Moira, his ex-typing-pool agent — on the island with them. How Stryker has gotten to the point where he can overrule the Director is not explained, but Stryker’s own arc, from underling to combatant to loose cannon, has been brief but well-defined.

Erik has seen all this coming, of course — he’s seen the demonization of the Other first hand. (He emerges from Shaw’s submarine with Shaw in a crucified pose — an odd choice, making Shaw Christ and Erik a vengeful Jew.) He’s completed his transition from victim to leader, from Erik to Magneto. (And, judging from his accent, from English to Irish, but that’s another matter. On second thought, the shift in Michael Fassbender’s accent may be intentional, from oppressor to oppressed, to better gain followers.) The element that had always threatened Erik’s relationship with Xavier, the suspicion and hatred of the Other, Xavier learns, is real and present, as the humans aim their guns for the island. The soldiers who, just minutes earlier, quaked at the thought of an international conflict, now happily fire on a tiny island with a handful of freakish civilians on it. The look on Moira’s face as she realizes her doom is priceless. Here she is, a high-ranking member of the Establishment, now slated to become collateral damage at the moment of her saving of the world. (On the other hand, as a young woman within that Establishment, she still counts as Other.)

Erik, of course, has the power to stop the incoming missiles, and has the power to dismantle them as well, to make them harmless. Xavier, at this moment, makes a terrible critical error — he defends the soldiers on the ships as innocent men only following orders — the Eichmann defense. Erik’s response, “Never again,” of course, is the motto of the western conscience (and, as Marie Brennan brings up in the comments, it is the slogan of the Jewish Defense League — a quite daring move, to equate Erik’s arc to that of European Jews from Auschwitz to Israel), but Erik here appropriates that sentiment to his own twisted purposes. He sends the missiles back to their ships as the ship’s captains suddenly turn noble again, realizing they’re about to die at the hands of a vengeful Other. Xavier, his mind-control tricks useless now, tries to distract Erik by tackling him. When that fails, Moira tries to shoot him. She fails, and Erik deflects one of her bullets into Xavier’s back. Crippling his friend is enough to distract him and the missiles crash safely into the waves.

Erik, pressing his advantage over the crippled Xavier, tries one last time to bring his friend to his side, but Xavier, even in his physical agony, cannot see Erik’s point of view. His goodness, his optimism, born of comfort and security, is too ingrained in him. Holding Xavier, Erik looks like he wants to kiss him, and I’m reminded that the helmet, that barrier, is Erik’s last defense against intimacy, like a chastity belt he wears on his head, to keep himself, his vengeance, his identity, pure. He loves Xavier but he cannot trust him, as well he should not, we’ve seen Xavier use plenty of people’s minds against them to think that he wouldn’t do it to anyone if it suited his purposes — out of goodness, of course, but that is always the way of the powerful liberal, always manipulating people’s minds for their own good.

Mystique joins Erik, as do Shaw’s men, but not before Mystique breaks up with Beast in her own way, reminding him to be “mutant and proud,” sowing the seeds of doubt in his mind. The others, Xavier’s recruits, go to his side, the good acolytes, the “kids from the bad side of the tracks” that have joined Xavier’s Boys’ Town.

Xavier ends where he began, at his home in Westchester, the carefree rogue now housebound forever, pushed in a wheelchair by a woman he once tried to seduce. Moira insists that she will never, ever tell the government where Xavier lives, as though a huge estate in upstate New York, where Xavier has lived since childhood, would be some kind of secret location. Leaning in for the kiss, Xavier makes Moira good on her promise and wipes her mind clean — control freak to the end. She goes back to the CIA a blank slate, prompting McCone to file her back to her original place: “This is why the CIA is no place for a woman,” he sighs, as Erik, now Magneto, arrives to retrieve Emma from the CIA’s secret prison (which, for some reason, is located at their headquarters at Langley). ”[Xavier’s departure] left a bit of a gap in life, if I’m to be honest,” he says to Emma, “I was rather hoping you would fill it.” Perhaps he’s speaking to Emma as a telepath, perhaps he’s speaking to her as a romantic interest, remembering her use as a sexual surrogate between him and Xavier, in this way becoming his own version of the two-timing Shaw.

The credits, kicking in, recall the Maurice Binder titles that made the James Bond movies distinct pop-art artifacts, even as Magneto’s cape and re-painted helmet signal the beginning of a new concept. X-Men: First Class, with its script that easily bests any half-dozen of the Bond movies’, even on their home turf, that is, in their cultural synthesis of the Cold War, makes its own case for pop-culture evolution: the better-adapted screenplay survives.

Captain America: The First Avenger, released concurrently, went back in time to place its difficult-to-like protagonist in his proper context

???

The writer’s revisionist view of history makes X-Men First Class look like a documentary. Idiotic “serious” analysis of comic book movies like this are what provide endless material for The Big Bang Theory.

Erik’s mother doesn’t have to be a mutant. Perhaps mutantism is a recessive gene and both mother and father had it? I don’t need to have red hair to have red haired children!

Also, Raven is far from a hideous monster…every red blooded man on earth would bed her as is.

Also, this is kinda long winded and overthought.

“X-Men: First Class” was a well made, entertaining movie, but it had anachronisms that detracted from it being a convincing “period piece.” The long hair, sideburns and mini-skirts didn’t become fashionable until a few years later. Crewcuts still ruled in ’62.