By Albert Fuzailof

Editor’s Note: Well this post ignited quite a firestorm. In case you wanted to hear the actual panel shown above here is the youtube video of it:

One of the benefits of being the showrunner of a comic con – I produce Cosmic Con – is that you get to meet and talk with some of your favorite creators. At my last con, I was talking to Joe Rubenstein (first Wolverine miniseries, The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe), who’s become a regular at my shows and a friend. Chatting about his career, he made a point that really stuck with me; “How many people do you suppose get to meet their idols and even work with them?”

“Imagine if you’re a sculptor or painter,” he said. “And meeting Michelangelo or da Vinci. Or a writer and getting to work with Shakespeare or Twain. In almost all fields that’s impossible, the masters who defined them are long gone. But I got to meet Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Jack Kirby, Stan Lee, Joe Kubert, Gill Kane, Wally Wood, Dick Giordano…I even got to work with some of them. I’ve been really, really lucky.”

This resonated. I’ve been a comics fan long enough to remember those pre-internet days, when dinosaurs roamed the earth and the only way to interact with creators was fan mail, fanzines, and conventions.

You’d get to read, and if you were lucky, listen to, creators tell stories about the old days, where they got their inspiration from, how they approached storytelling, and other peeks behind the curtain that made being a fan so much more interesting and fun.

No one goes into comics for the big bucks. Creators were happy to share their personal anecdotes and thoughts with readers who loved comics like they do.

There were still industry controversies fans talked about, of course—how Siegel and Shuster were treated horribly by DC, how Jack Kirby and Stan Lee fell out, how Marvel kept changing editors in chief—but you had to buy The Comics Buyer’s Guide or Alter Ego to learn about them.

And there were always vocal fans. When a new Batman movie was announced, and fans thought that having zany director Tim Burton and comedy actor Michael Keaton meant it was going to be campy like the 1966 TV show, they had to write in to their local newspaper to protest.

When Hal Jordan became Parallax and destroyed the Green Lantern Corps, the fan group H.E.A.T. (Hal’s Emerald Advancement Team) wrote angry letters to DC and took out an ad in Wizard magazine. (The internet existed back then, but it was excruciatingly slow and mostly just screamed at you.)

Sharing opinions, whether positive or negative, required time and effort. Because of that, fans had to take the time to think and express themselves in a way that’d get attention. Even when irate, they had to be thoughtful, constructive, and civil.

Then came the internet and social media. “Social media has certainly enshittified fandom as much as it has everything else in the 21st century,” Mark Waid told me in an email. “There’ve always been brickbat-throwers out there, but when they had to actually write a letter and buy a stamp, you didn’t hear from them as much. Once all they had to do was open a Twitter account, the horse was loose in the hospital.”

I wrote to Mark after reading George R.R. Martin’s blog post, where he lamented that “the era of rational discourse seems to have ended.” Martin started out as a comic book fan. His first published work was a fan letter in Fantastic Four #20, and he’s credited with being the first attendee of the first comic con. Over the years since he’s seen fandom change, and unfortunately not for the better.

“Toxicity is growing. It used to be fun talking about our favorite books and films and having spirited debates with fans who saw things different,” he wrote. “But somehow in this age of social media, it is no longer enough to say, “I did not like book X or film Y, and here’s why.” Now social media is ruled by anti-fans who would rather talk about the stuff they hate than the stuff they love, and delight in dancing on the graves of anyone whose film has flopped.”

This new fandom, which has come to be called toxic fandom, is still just a subset—many more people buy a comic than post angrily about it—but it’s a loud and unpleasant one. Entitled, addicted to outrage, and harmful to the very industry they claim to care about.

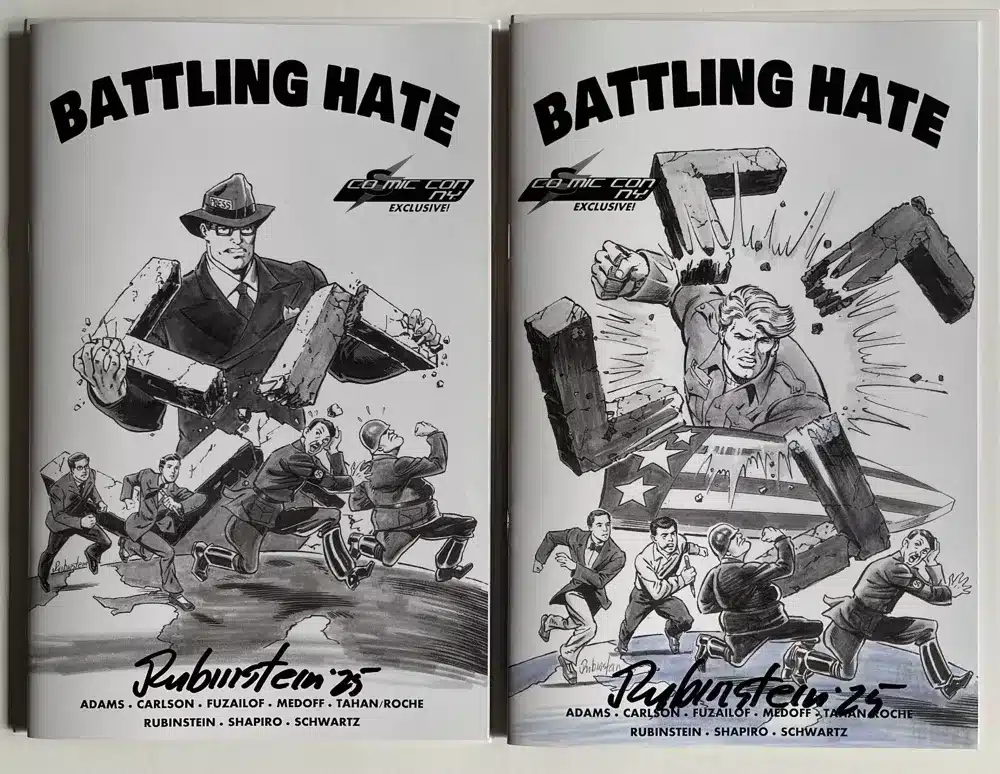

Each Cosmic Con centers on a theme, and for our last show this past February, the theme was “Battling Hate.” We especially wanted to highlight how, from the industry’s early days, Superheroes fought against fascism and intolerance, to over eight decades of stories mixing in adventures, suspense and thrills with a healthy dose of morality. Helping define right from wrong, in the minds of both young adults and teenagers, setting the stage for “Truth, Justice and the American Way”. We had a “Battling Hate” panel, featuring an all-star lineup: Rags Morales, Ann Nocenti, Alisa Kwitney, Danny Fingeroth, Keith Williams, and Joe Illidge.

These industry veterans told me that on many occasions they’ve received online backlash and personal attacks, so they just stopped sharing anything beyond whatever project they were promoting.

Roy Thomas, a fan-turned-pro who went on to become an industry legend, cordially declined participating in the comic. “I received quite a bit of toxic hate beginning last April when it was announced that I’d be credited in Deadpool & Wolverine as co-creator of Wolverine,” he wrote to me. “It made me determined…[to avoid] a con where I might find myself in the company of the people who had attacked me.” He’s written an article about the ordeal for an upcoming issue of his own magazine, Alter Ego #194. [See editor’s note below.]

This soft-spoken, erudite, 84-year-old man has been bullied into silence. And because of that, the rest of us are missing out on a treasure of stories and knowledge. There aren’t many Bronze Age creators left, every day we lose some of that history.

“The intensity of fan reactions was different in the 80s and 90s,” Ann Nocenti told me. “Fans would send passionate letters, sometimes up to six pages, single spaced. The language and context were more moderate, because fans who took the time to write or type their grievances, were aware that no one would read their comments if they were nasty or profane. The internet brought anonymity. Now comments can devolve into profane tirades, and no one can call them out. Since there is no accountability, some feel they can get away with being vulgar and offensive.”

“Embattled pros who aren’t white dudes like me,” Waid notes, “I know how much worse they get it. When I was embroiled with that nuisance suit a few years ago that involved ComicsGate, younger creators were privately sharing with me incidents [and] posts…they had received from æfandom,’ and they were plentiful and…repulsive.”

“Yeah, it’s easy to say ‘well, they should just ignore that stuff,’ but the newer you are at this, the more you depend on social media for promotion. It’s a necessary evil, and most contemporary creators don’t have the luxury of walling themselves off absolutely from social media.”

This culture of incivility has migrated from the virtual to the real world, and, sadly, even from fans to some professionals. Larry Hama is a third generation Japanese American and a Vietnam vet. When he first started writing the property he’s most known for, G.I Joe “I was called ‘a fascist’ by a fellow professional. It was during a public event, in front of colleagues and my wife.” When Larry asked the guy if he bothered to read the books, he answered, “I don’t need to read them to know what they’re about.”

When we forget that the creator we’re interacting with is a human being, and when we insult, harass, or intimidate them, or when we see others do it and say nothing, we all lose out. We miss out on their stories, opinions, and tips about the very thing we love. Shutting down our “primary sources” makes fandom a less pleasant place and comics a less fun hobby.

The first recorded Toxic Fan incident that I am aware of involved Jack Kirby. Back in the days of Simon and Kirby working out of Timely (Later Marvel) offices, writing Captain America stories trouncing Fascists and Nazis. Apparently, some Toxic fans (Supremacists, in this particular case) took issue with that and called the Timely office, spewing curses and threats. According to legend, Kirby took the call and in the tense exchange, was threatened in being beaten to a pulp if the “fan” was ever to meet him at a street corner. Kirby offered to run down to the corner and resolve this dispute at the nearest street corner. Co-workers mention that Kirby ran downstairs in anticipation of a fight, just to have this particular caller chicken out.

Waid sums it up: “Fans are great. But toxic fans aren’t “fans” at all, so fuck ’em.”

So please, let’s remember to be pleasant. Being civil is not expensive, it may even get the point across. It’s what superheroes would do.

With special thanks to Roy Schwartz.

- Editor’s Note: It should be noted that Thomas’s new credit for co-creating Wolverine has been controversial among his peers as well as fans.

As someone who was personally attacked by HEAT (I was responsible for moderating the DC AOL message boards where they gathered), I can attest that the toxicity has been around longer than you suspect.

Respectfully, I think you conflate way too many things. And as Johanna pointed out, there’s been toxicity going on for a while. Roy Thomas being attacked for his bs credit-grabbing is not the same as many creators (who you did NOT interview and quote in this article btw) who are attacked for their race, their gender, their gender identity. The internet has definitely made things worse but write a half-assed article where Roy Thomas laments how people attack him as a greedy credit-hog after he…is publicly a greedy credit hog, and compare that to people being attacked for their identity shows you missed the point. Waid is right. People get attacked a lot and in extreme ways. And your framing is far too dismissive of all that they endure.

(Also, respectfully, I love all the cartoonists you named at the beginning, but to compare them to Michelangelo and Da Vinci and Shakespeare….no. Maybe that’s me being toxic)

This article sucks because I was interested to hear what the panel was like and what those people had to say about battling hate. You keep quoting mark waid for some reason. The Roy Tomas claim seems flimsy. Nobody in this article was silenced and if they were you didn’t talk about it. If you’re talking about backlash you receive from a controversial move you made in a magazine that you publish you’re not exactly being silenced and that’s the only example you used to prop up your click bait article title. It doesn’t seem like we’re missing out on any comics. Hearing what the panel had to say unfiltered would be an actually interesting read. Is there a video or transcript?

This article is a disgusting travesty- for one thing, it speaks volumes that it has a credit by Heidi MacDonald before revealing it’s by the showrunner of Cosmic Con- but the fact that it implies any criticism of professionals is akin to hate speech is bad enough. Roy Thomas has been an outspoken conservative for decades- which is his right- and says things in print (!) like he refuses to capitalize “Black” in “Black people” until “White” for “White people” gets equal capitalization. Thomas’s Alter Ego features regular contributions from journalist James Rosen, who was too extreme for FOX NEWS (!), and now works for Newsmax, a conversative channel that pushes the great displacement theory that immigrants are here to steal votes from White people.

It’s nonsense. Thomas and his manager John Cimino have repeatedly posted that they’ve received death threats; it’s a deflection tactic to move attention away from blatant and disgusting credit theft. I’m amazed there’s no mention in this article about the repeated racial and sexist attacks on creators that have continued for years, especially increasing in modern times with middle aged white male comic fans who complain that comics have gotten “too woke”.

“This soft-spoken, erudite, 84-year-old man has been bullied into silence.” It’s disgusting but also rather easily disproven, since Thomas has not been bullied (called into accountability for your deeds is not bullying), and certainly hasn’t been SILENT as his upcoming issue (great it got a plug in this article! THAT’S being “bullied into silence”) of Alter Ego attests.

There are hateful, racist pricks in every community. As someone who actively fights against said racist pricks, I find it astonishing that online criticism against people who actively seek payment to autograph things- therefore making them public figures- makes them equate that with bullying and being silenced.

Here’s a tip: if you’re being bullied for taking positive stances against hate, screw the bullies. Get louder. If you’re curiously changing the narrative of your career and contradicting decades of previously recorded statements, guess what- people are gonna comment on that. And that’s not bullying.

Heidi, you should never have approved this bulls**t. Or at least rewrote it!

It’s also just bad “journalism” when the tagline under the article header says “when making comics get you death threats” and then literally doesn’t reference the most recent and most noticeable case involving Dan Slott a little over a decade ago. Baffling, amateurish writing here.

Amidst his bizarre equation of critics of Roy Thomas (ironically, Mark Waid among them!) with Neo-Nazis, the con promoter inadvertently highlights a few issues worth considering. Is all harsh public criticism “hate”? Is there any behavior in any circumstance that warrants harsh public criticism?

P.S. I’d love to know both how this column was pitched and how it was received editorially.

“Hey, I’d like to write an article on the dangers of toxic fandom.”

“Sounds good! Whatcha got?”

“If you don’t think Roy Thomas is the creator of Wolverine, you’re a Nazi.”

“Well… not sure I entirely agree with your conclusion there, but… guess I’m committed to running it now. I’ll throw in an editor’s note to keep it fair and balanced.”

I get what you were going for here, but quoting Mark Waid (who, if I remember correctly, once doxxed comic journalist Jude Terror of The Outhousers and Bleeding Cool) at length in an article about online toxicity, and then also conflating it with the justified outrage from creators regarding Roy Thomas’s loathsome rights-grab is not the way to do it. Like John Lennon said, “if you go carrying pictures of Chairman Mao, you ain’t gonna make it with anyone anyhow.”

Respectfully, it is difficult to follow the thread of this article. The title suggests that it will cover creators who are being silenced but the only one mentioned as directly experiencing this is someone who produces his own magazine (which will likely provide a very one-sided account of a story that has already received significant coverage). Even his determination to “avoid a con” that might include his attackers feels odd given he is a headline at this year’s Heroes Convention, one of the largest gatherings of comic book fans and professionals.

The article also feels routed in the past. To demonstrate that the “culture of incivility has migrated from the virtual to the real world”, an experience that the brilliant Larry Hama had is cited. However, this incident happened when he “first started writing” GI Joe, meaning it occurred in the early to mid-1980s. Anti-Keaton protests (1989), HEAT (1996), the ComicsGate lawsuit (2018-2020) – I’ve lived through them all and surely it would not have required turning over too many rocks, even if the sources were anonymous, to provide more current examples of the kind of behavior discussed in the article.

As a final thought, any article that attempts to talk about toxicity and suppression can only be enhanced bringing in the voices of those who are not, as Mr. Waid noted, white dudes like me.

four color sinners already eviscerated this article lol

i was also curious if he meant Slott during his ASM run

The author put together a panel at his convention to address the subject of his article. The article largely consists of quotes from Roy Thomas and Mark Waid. Were are quotes from his panel (Rags Morales, Ann Nocenti, Alisa Kwitney, Danny Fingeroth, Keith Williams, and Joe Illidge)?

The panelists were an ethnically and genderwise diverse group, and most of them are younger than the two “old White guys” (quote marks to indicate a phrase, not a quote from the author) who’s stories dominates the article. I believe there had to be more compelling content for the article spoken by the panelists than what the author provided here.

Being an “old White guy” myself, I feel it is much easier to discuss “hate” with other Whites than with people who are ready to blame me… That may have been a part of how this article ended up with this content.

I am not personally aware of much that was discussed in the article. I left social media in 2016 to escape the toxicity. My impression is that hate is the greatest power on Earth today and will define this century, so I am not ready to dispute the premise of this article.

I do think the article is a misfire and shouldn’t have been run in this form.

For everyone wishing that someone who was not a “white dude” was quoted….the piece literally quotes Ann Nocenti and Larry Hama who are not white dudes! Kind of makes me question your reading comprehension.

Albert Fuzailof is on vacation, so he might be slow to respond but I will add that in our discussions of this piece he mentioned that he did reach out to more marginalized creators but they did not want to participate in the piece.

And to be honest, I can understand why. I have been the recipient of many death threats, rape threats and name-calling over the years, and I’m called the C-word on the regular-degular. My own stance is that drawing attention to such things (instead of reporting them, where possible) is exactly why they were made in the first place. I’m sure a lot of marginalized creators feel the same way.

I think it’s interesting that commenters are outraged that people are are suffering from bigoted attacks don’t want to relive or enumerate those attacks. Do we really need another article exploiting their trauma? That Nocenti and Hama spoke up about toxic fandom without referencing sexism or racism somehow made their comments irrelevant? Are they only allowed to talk about themselves in that frame of reference? That seems odd to me.

There could be reasons other than fan harassment why somebody wouldn’t want to be associated with this article. Heck, some of those quoted may feel that way after reading the finished piece.

Waid says fans are toxic. I mentioned that Jack Kirby at least knew basic science in regards to the Fantastic Four story that he did “Marvel style ” with Neal Adams.

I never considered that Adams actually did the story, so the science was a little off.

Waid blocked me. I wasn’t disrespectful. I did point out what i objected to . There was no further discussion. I was blocked.

So there should be no worries about toxic fans on line. They can ignore them and i can ignore buying their books.

maybe including larry hama in an article with roy when larry stated how roy fired him from a book, and dismissed him as only being able to do kung-fu comics wasnt the best idea. but! roy thomas is bullied lmao

@Michael- yeah, Waid is famously prickly and has even implied fighting dudes over online clashes. he was quite a firecracker on newsarama lol

The last comics journalism publication I trusted not to be a bunch of sycophantic nonsense was Joe Brancatelli’s INSIDE COMICS. And even back then, fifty years ago, his approach chafed folks like my acquaintance, Marty Greim, who wrote a letter bemoaning the trend to treat comic books and the people behind them as anything but fun, fun, fun all the time. I get it. Part of the reason for reading them is to leave the real world for a time. But when someone BEHAVES badly, it isn’t controversial to call them out. And when their consistent behavior is a singular inability to take criticism of ANY kind, then it is not bullying to shun them, who in the world wants to hang around someone like that on any regular basis?

And, it’s not bullying to comment on their WORK fairly. And by fairly, I mean what’s there on the printed page. For example, when reading Conan #1 -35 in real time, I couldn’t help but notice a big drop-off in quality of the stories, pacing, and character development after Barry Windsor Smith left at #24. So I stopped buying it. The end.

When at my first convention in 1970, Roy Thomas would often hold court with at least five – eight fans around him as he detailed his approach to the books and Marvel’s upcoming plans. At the time, he was one of US! Fandom boy makes good! It was sincerely exciting, and he was a great promoter of the line and connected with us. A ten-year-old kid came barging up and asked him the clichéd question, “How do you get your ideas?” Roy answered the question seriously without demeaning the kid while us mature 15-20 year olds stood behind the kid, smirking and silently chuckling.

Unfortunately, over the years it expanded to answering every perceived slight from fans and pros alike. Constantly. When an artist rightfully bemoaned being treated less than by Marvel and/or Roy, it was their fault, according to him in his passive-aggressive manner.

I’m sorry for his sake that more introspection or someone to gently nudge him to ease up never happened. But “muzzled”? “cancelled?” It is to laugh. And it cheapens artists/writers around the globe who are paying REAL horrible prices to practice telling truth to power.

As Stan Lee found out, surrounding yourself with yes men leaves you alone. As does stealing credit not belonging to you. A reevaluation is taking place where more and more truth about Lee’s behavior is spreading to a wider media. I suggest, truly, Thomas spend his time reevaluating while he’s on this side of the veil how he wants his legacy to read.

I’m not disagreeing with this article. The comic fandom is insane. No creator should be attacked in such a matter that makes them feels scared for their life let alone needs police intervention.

I do find it funny you spoke with Mark Waid. Mark lead a toxic fan brigade against Antarctic Press when they were going to print Richard C. Meyer’s book. Toxic fans flooded all of the phone lines to a hospital that even emergency calls couldn’t get in or out.

Let us not forget the time Tim Doyle lead a group of fans against the Breitweisers because Mitch publicly congratulated Donald Trump for winning the 2016 election. This resulted in Betty getting multiple rape threats and the both receiving death threats.

Then there was the vandalism and threats against the Florida pizza place, Gotham City Pizza, for hosting Ethan van Sciver. Thankfully, many of Ethan’s fans raised more than enough to pay for the damages and a security system to catch further attacks.

I understand why Comics Beat wouldn’t include these testimonies of toxic fandom. These creators “voted wrong” and therefore many involved with this site would think that is justified. Most deranged and violent people often try to find justifications for their malevolent behavior.

I find it pretty funny that anyone would listen to Mark Waid’s opinion on this subject when he himself has been the lead on many cancelations of creators that had a different opinion than him.

Heidi macdonald doesn’t understand that the problem is this whole article(not literally) is mark waid and Roy Tomas. It’s one sentence from Larry hama and Ann nocenti.

Then you’re trying to paint a picture of people criticizing the article that denies any nuance. You’re saying we’re making the argument that the statements from Larry hamma and Ann nocenti are invalid for some reason you made up. That’s not what we’re saying and you should know that.

Saying the author reached out to other creators who didn’t want to comment, to me suggests they heard about this click/rage bait article and didn’t want to be associated with it. Heidi suggests that the other people who were contacted are all being silenced.

To the author Maybe forget about quoting a bunch of people and tell us who’s being silenced, how, why, and is it justified or is it wrong. Your title says something that the article doesn’t really support. The panel discussion seems like it’s going to be relevent but it’s just mentioned briefly to give you some cred and then forgotten about. I had to find it myself on youtube.

Imo the whole article should just be drawing attention to the panel and spreading those ideas assuming you think that conversation is important and relevent. It kinda seems like you missed the point and just gave us click bait and mark waid quotes.

https://youtu.be/UpdCTPQTnRc?si=DwZNtJLEL7qvMd7P

Furthermore’s post above is a disingenuous example of the toxic discourse that always arises whenever these topics are broached. The creator he mentions has made countless bigoted posts attacking people based on their ethnicity, gender or appearance. He’s attacked me numerous times as a “dumb c—” – I guess I must have generated a lot of clicks because he kept attacking me for years. Free speech means you can call someone names, but it also means I can stop inviting you to my house for dinner after you do. That a publisher supported these kinds of attacks by publishing this work showed questionable judgement for many people, and that is why there was pushback. As he said himself “Most deranged and violent people often try to find justifications for their malevolent behavior,”and that goes for EVERYONE.

Please remember to be civil in these comments.

Furthermore, your last sentence is spot on. MAGA supporters prove it every single day.

People making threats online are really using terrorist techniques because they can’t plead their argument verbally or- more importantly- in person. I’d have a lot more respect for someone that hated my articles but showed up rather than leave troll comments.

I was unaware that EVS made such horrific comments about HM, I do remember someone relaying to me that EVS said that DC hired more women writers and this was HM’s fault for harassing the then-publisher to do it; I said, if anyone can affect change just by harassing terrible figureheads, more power to them.

EVS knows what he’s doing. The fact that he and Mark Waid were so pompous and pumped up after confronting Rob Granito only told me that neither of them had ever been in a real fight.

I agree with Heidi that the behavior of the some people mentioned by furthermore is at times unacceptable. I disagree that those instances justify illegal retaliation. Nobody should be getting rape or death threats.

If anyone is deserving of airborne brickbats it’s Waid. It doesn’t take a deep dive into his history to learn just how radical this “industry legend” has become.

I’m of the opinion that, if you can’t say something nice about it (whatever “it” is,) don’t say anything at all.

And to these “toxic fans,” I say….

“Waid says fans are toxic.” That’s toxic fandom in a nutshell, folks–doing shit like turning the quote “Fans are great. But toxic fans aren’t ‘fans’ at all” into “Waid says fans are toxic” and then posting it as if it were fact. A+ for volunteering up a clear-cut example, dude.

Like 99.9% of pros, we like and respect our fans. Maybe you’re a fan who has had a bad pro interaction, even one with me. That’s certainly possible–we’re all human, plus it’s easy to misinterpret anyone’s words or actions, pro or fan, in the chaos of a convention. But way more often than not, “xxx was a jerk to me online or at a show/blocked me/was mean to me, they’re the real toxic ones!” = “I came at them windmilling my arms and was rude, and they had the temerity to not take my shit and treat me as nicely as they treated others!”

Look, the vast majority of us go out of our way at signings and conventions to make every fan feel seen and heard. If you’re not a toxic fan, I don’t have to tell you that, you already know it. And we’ll listen to polite, respectful criticism and take from it anything we feel might have merit, certainly. Genuine fans know this and have seen this first-hand. That’s why they’re never the ones who come guns-blazing into these discussions to defend themselves or try to turn tables–because they know we’re not referring to them. I mean, you can see it for yourselves. There are already a handful of posters in this thread already, and there will be more, who couldn’t help but out themselves, and it’s obvious to everyone but them who they are.

House Roy taking shit for claiming a credit he absolutely doesn’t deserve is not “bigotry.”

Roy Thomas made his bed, and I feel it is pretty disingenuous to paint him as any kind of a victim. Mark Waid is generally well intentioned, but you can’t fight in the mud and not expect to get a little bit on you. I think creators should probably try to become less accessible online, and I think a lot of these issues would lessen to a large degree. Familiarity breeds contempt, and all that. Some of the most respected and loved creators have a pretty small digital footprint, or they mostly spend their time promoting their work and not engaging in politics, social commentary, industry commentary, etc.

waid is obviously referring to the commentators here who mentioned him, ok.

katang is right, slott telling someone online to ‘go f yourself’ shouldnt happen. i mean, fans shouldnt threaten comic pros or anybody but just let your bosses handle that, report it. theres also a loss of mysique when pros are always present and communicating and commenting its why i never got into byrne because i cant enjoy his stories when his presence and including himself in stories soooooo much takes me out of it

That’s right and no one said it is?????????

Does everyone just skim every third word of what they read now?

The article doesn’t do a good job of clearly delineating between a few specific things that are being woven together:

1) Comics creators (or anyone) being harassed–this is toxic behavior

2) Comics creators being harassed for political views, their race, identity, gender, etc–this is toxic behavior

3) Poor old Roy Thomas just trying to be the befuddled bemused grandpa of modern comics and not being able to swipe whatever credit he wants for work he did not do, and people calling him out on it, and him not liking it–this is not toxic behavior

If Roy Thomas (or anyone) is legitimately being harassed, that’s wrong. But the article doesn’t really just dwell on his harassment; it seems to suggest that he should be allowed to do whatever he wants with his creative and professional life, and if he’s not allowed to happily be regarded as some kind of historical icon living legend, that’s an injustice.

Honestly you have a much better article if you take Roy out of it completely.

This is a fantastic article, and I think the string of toxic comments here are is an amazing visual aid to prove your point beyond a shadow of a doubt. I don’t know how you got all these crocodile tears in one comments space, but it’s incredible. Good work.

Mark Waid is an absolute hypocrite. He has spread false rumors online and bashed people without proof or facts. His audacity here is ridiculous.

I would caution that political beliefs are a free speech issue (here, it’s still not considered hate speech to “attack” someone’s political views), whereas race and gender dicrimination is a human rights issue (here, toxic behavior and language here could be a crime) — in other words, it doesn’t make sense to me to conflate online attacks for politcal beliefs and online attacks that are directed at identity. Silence is free, but you can’t change the color of your skin, who you love, if you born able bodies, etc.

Comments are closed.