By Andrew Warrick

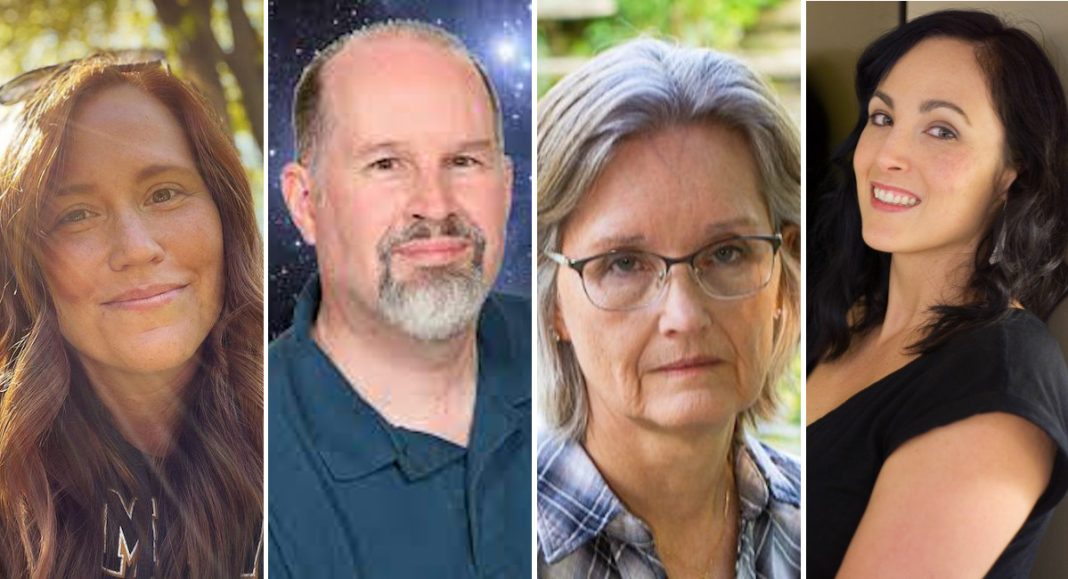

On Friday evening at C2E2, science fiction writers Timothy Zahn (Star Wars: Thrawn), Delilah S. Dawson (Star Wars: The Skywalker Saga), J.S. Dewes (The Last Watch), and Sue Burke (Semiosis) came together for a panel to discuss world-building.

Zahn chose the science fiction genre because of “the chance to build a new world, build a new society,” saying that other genres, like mystery or romantic comedies, were “stuck with” Earth.

“You’re getting to be a god,” Dawson added, saying she was inspired by science fiction movies and TV shows, such as Krull and Buck Rogers, watched with her father. She also called it “A super fun chance to kill your friends in print… we all hide names in there… I tried to kill my husband on the toilet, they wouldn’t let me.”

Burke was drawn to the science fiction section of her school library, and “read everything” until running out of books.

Asked about scientific accuracy, Dewes said “it’s definitely something I try,” but acknowledged that it was impossible to be comprehensive. Accuracy is important to Burke’s current work-in-progress, which involves our solar system. The alien, futuristic characteristics of Zahn’s work mean that he does not have to worry about current scientific capabilities, and he asserted that Sci-Fi writers must avoid overloading their work with science. However, he once needed to prove to an Analog editor that a plane’s landing was physically possible–– which he did by running the numbers himself.

“I don’t care about science at all,” Dawson said, talking about her first book series: a paranormal romance. When a reader asked her about the chemical composition of her steampunk train’s smoke, she remembered telling them “You should be reading this for the vampires and the sex scenes.”

Both Dawson and Zahn have written Star Wars novels, and they were asked if editors limited their work’s scope. Dawson explained how writers are usually given exactly what the editors are looking for, though, “within those parameters, we usually have a lot of leeway to do all sorts of things.” One has to be careful not to mess up the canon, however, because people get “very, very upset.”

“With something like Star Wars, we talk about internal consistency,” Zahn added. “You not only have to look at what they’ve done, but what they haven’t done.” He recalled talking with West End Games developers about how hyperdrive worked and trying to come up with the canon-appropriate deceleration process.

The panel then opened up for audience questions.

Asked about the hyperdrive-destruction scene in The Last Jedi, Zahn called it “a problem for me because if this works, you should have seen it being done in the Clone Wars… [it was] just invented for the movie without consideration of what had gone before… Inconsistencies drive me out of the story, whether it’s a movie or a book… it doesn’t feel real.” He noted, however, “not my circus, not my monkeys.”

Asked about her process, Dewes said she figures out her main concept, how the characters and plot work with it, and then uses world-building to support everything. Typically, she adds world building in succeeding drafts. Burke’s world-building process is similar: “Go through it again and again to try to put in all the details that you need.” “When I’m doing world building, what I’m looking for is a chance to make conflict,” she explained. For her novel Semiosis, Burke used the iron present in the human body to create conflict.

Zahn starts with the basic plot, builds in the necessary characters for that story, and folds the world-building in as he goes. He gave the audience an acronym for making a culture: PERSIA (Political, Economic, Religious, Social, Intellectual, Artistic). Dawson begins with a character, and creates “a world that would uniquely challenge that character and push them… you want to torture this character as much as possible.”

“Your dinner parties must be a lot of fun,” Zahn replied. He went on to say that a writer must avoid filling in their map, because “you may suddenly decide there was a desert here, I want a volcano instead, and it’s too late.”

Dawson gave another world-building tip: avoid monocultures where “everyone has the same haircut and eats the same food and wears that same outfit. That doesn’t really exist.”

On sequels, Dewes said “honestly, I was so sick of this [her most recent] book,” though she does want to return to certain characters and has a Patreon to do just that. Burke replied that sequels depend on whether or not her publisher pays for them: “I got to pay a mortgage. And if I can’t sell it, then there’s no point in me writing it.” Zahn recalled wanting to write a sequel to a book written twenty years ago. It took until 2020 to come up with the story idea–– “I don’t want to run over the same territory again just to visit the characters. It’s got to be something new and fresh.”

“As soon as I’m done with something… I’ve completely forgotten about it,” Dawson said, though she revealed “I don’t think Phasma is dead” and has pitched a sequel where the character becomes a petty warlord. “Fingers crossed… I haven’t seen a body.”

The next topic brought up was exposition. Zahn breaks it into chunks. Dewes utilizes dialogue. “You want to avoid the elf wars,” Dawson said, referencing The Fellowship of The Ring’s long prologue, detailing how many writers are so enamoured with their world that they start with twelve pages of history, leaving readers to wonder “is there a main character?” Instead, according to Dawson, one should provide exposition through one’s characters.

“Please do not have characters explain to each other what they both already know,” Zahn said.

An audience member asked about handling different languages within one’s world, or even one character. Zahn provided an example: “‘That’s a good question,’ he said in German.”

Another attendant questioned if any of the writers had come up with ideas too wild for even science fiction, such as a dolphin on a spaceship. Dewes replied that she was stubborn, and finishes anything she starts. Burke never begins a story without knowing how it will end. For Zahn, it is a matter of making a story that reflects, and relies on, characters and their choices. Dawson acknowledged that many of her early stories petered out but, now that she outlines, her writing usually makes it over the finish line. She swore that, if a writer is conscientious and keeps the characters consistent, “you can totally have a dolphin on a spaceship.”

Dawson explained that it is important to write one’s first draft without self-criticism, comparing it to carrying hot laundry: “you just run as fast as you can to the bed and you drop socks, whatever. Get the book out of you without judging yourself.”

The next question concerned the visual identity of one’s imaginary world. Dewes tries not to get “bogged down” in description, and lets the reader imagine things. “You don’t need a lot of description,” Burke seconded. Zahn also goes light on description, saying readers fill in the gaps.

Dawson relies on other senses, such as smells and sounds, to keep readers from getting bored. She recalled visiting the Star Wars Galaxy’s Edge theme park before opening day, and asking the imagineers what it smelled like. They looked at one another, eyes wide, and replied “we didn’t think about that.”

The next topic was the food and fashion of one’s fictional world. Dawson asserted the importance of leaning into unique descriptions, keeping the reader’s experience in mind, and making sure they match one’s world and its rules.

The panel ended with advice the published writers would give aspiring authors. Dewes said to read widely, across genres, and “Find your people,” using a writing group that responds to and inspires one’s work. Burke replied that “the more you know about the story before you start writing, the easier it’s going to be. I want it to be as easy it can be for you so that you don’t die writing.” Zahn told writers to remember that, while world-building is important, “your story is about the people.” Dawson said not to judge oneself on the first draft- “if you reread your pages constantly looking for mistakes, you’ll never get past them… a really crappy first draft is worth more than 1,000 perfect first pages”- and to avoid people who take advantage of up-and-coming writers.

Miss any of our previous C2E2 ’21 coverage? Find it all here!