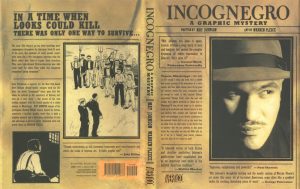

Incognegro

Written by Mat Johnson

Art by Warren Pleece

Lettered by Clem Robins

Originally published by Vertigo Comics

Current edition published by Berger Books/Dark Horse Comics

There’s a highly volatile and dangerously controversial debate within American racial politics about the different tones of color a person’s skin can take. It’s a matter of identity. What color skintone makes one a black person? What tone falls within the category of white? It ranges from black people to Latinos and even to white people (people from all over in any case). In come discussions on colorism, on whether people with darker skin tones are discriminated against more than people with lighter skin tones, regardless of both being considered people of color.

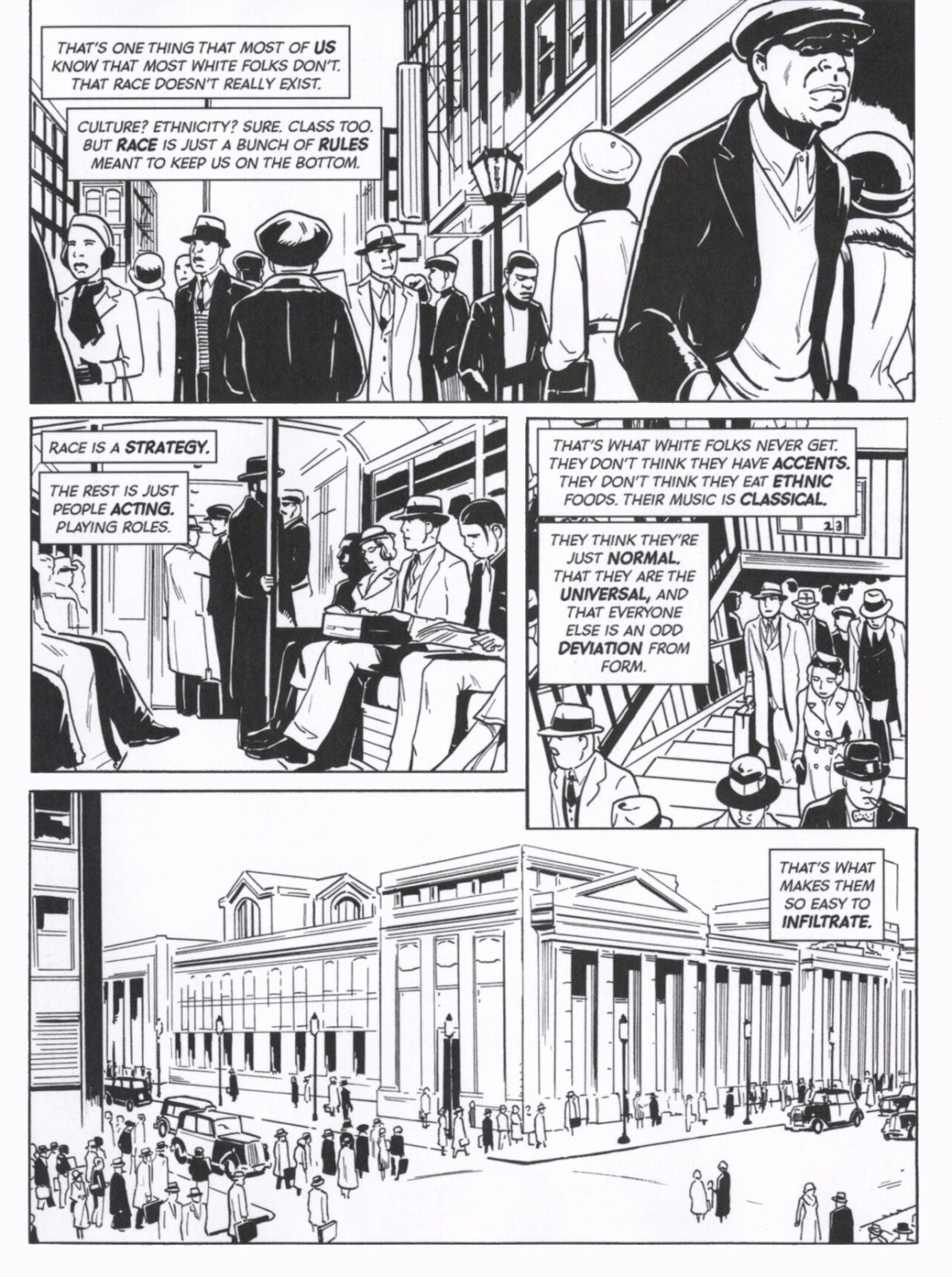

It can leave one feeling as if they’re suspended in a kind of in-between state, a question mark many don’t really know where to place. Mat Johnson and Warren Pleece’s 2008 graphic novel Incognegro explores such matters, but it does so with a fascinating twist driving the discussion: it puts a light skin-colored black man in the role of an undercover journalist in early 20th century Mississippi, a hotbed of lynchings and racial animosity.

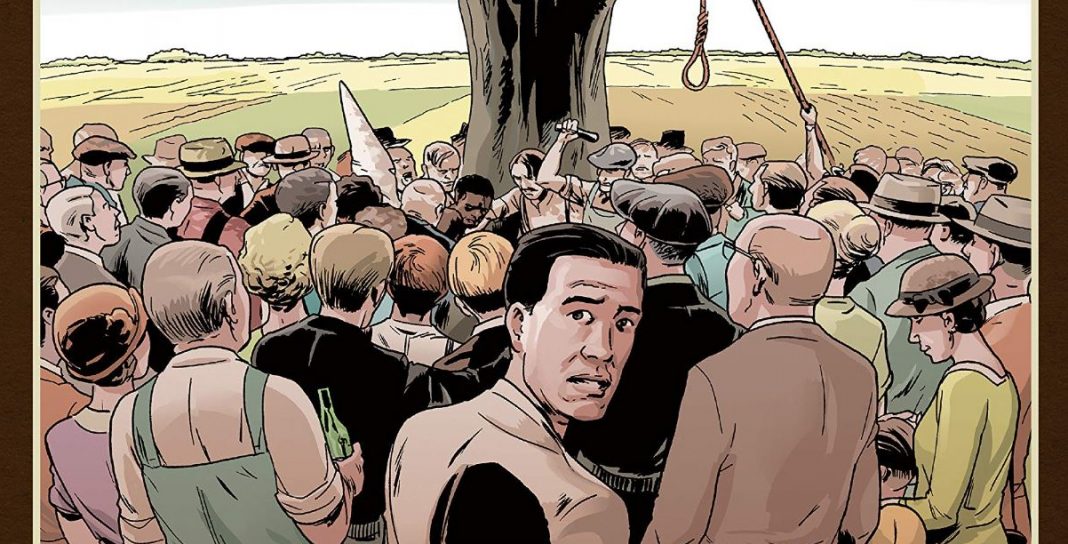

The journalist in question is Zane Pinchback, a black reporter living in New York who travels south and goes incognegro for one last time after receiving news of his brother’s arrest in the Mississippi. His brother’s been accused of murdering a white woman, and unless Zane can manage to clear his name, or at the very least break him out of jail and out of the South, it’s very likely his brother’s going to end up the victim of a lynch mob.

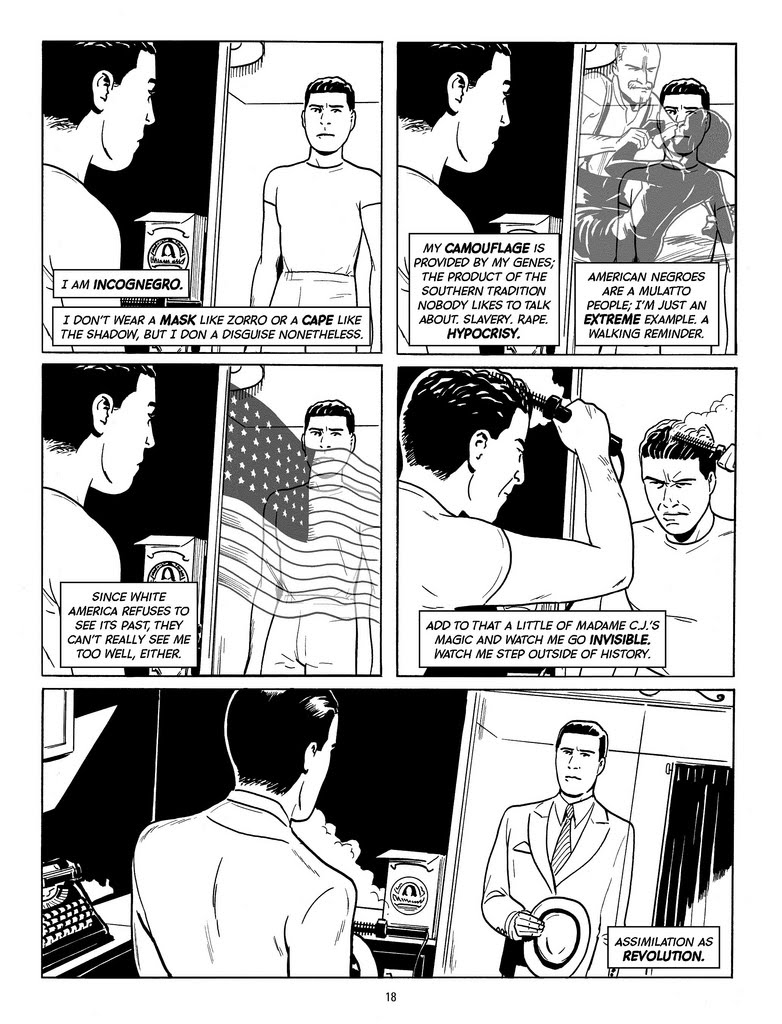

The story draws from Mat Johnson’s own experience with being a light-skinned African-American man. In his introduction to the 2018 edition of the book (published under Dark Horse’s Berger Books imprint), Johnson states: “I grew up a black boy who looked white…My mom even got me a dashiki so I could fit in with the other kids, but the contrast between the colorful African garb and my nearly blond, straight brown hair just made things worse.”

He goes on to explain how he had dreams of “going incognegro” to infiltrate white supremacist groups, to expose their plans. He also explains that his interest in civil rights activist Walter White, the former head of the NAACP who himself went incognegro to investigate lynchings in the South, also came to define the book.

Johnson and Pleece make an important decision by presenting the book in black and white. The absence of full colors is not so much an attempt at avoiding the discussion as it is a challenge to it. As a reader, one is forced to imagine how light Zane’s skin color truly is. It also allows for an even more difficult exercise: debating whether his physical features can reveal his true identity.

It’s a unique kind of tension that Johnson and Pleece manage to extract from this set of intensely visual ideas. I found myself worrying over Zane’s “racial tells” every time a new white character interacted with him. It made me question whether I was being too superficial in my fears just by focusing on the character’s physical traits. What did this say about me as a reader? As a person?

Incognegro does not take for granted the unique position it puts its readers in. As Zane melts into his undercover identity and navigates dangerous white spaces, he comes across black characters that can see beyond the racial disguise. Some do so by witnessing his actions, others by taking a closer look at him. The discussion turns even more complicated then. Is it actions and the recognition of a shared experience that make someone black? How much of it is skin color and how much of it is behavior?

These questions aren’t exclusive to people of color in the comic. The story’s villain, a high-ranking member of the KKK’s head office in Mississippi, also adds a wrinkle or two into the equation and makes for a finale that brings even more questions into the fray. Ultimately there are no easy answers to any of the questions put forth by the book, and by extension, there are no definitive answers to aspire to either. Race is too rich in form and variation to conform to any singular idea of identity. That’s something not everyone is willing to accept or understand.

Zane’s racially charged voyage into the South—for justice, no less—makes the book essential reading in the times of the Black Lives Matter movement and its call for social accountability for racist behavior. Johnson and Pleece’s work is exemplary and manages to be accessible despite the very difficult questions it poses. Nonetheless, they’re questions that need to be asked, and that dare us to give them an answer.