In two recent releases, Whit Taylor uses her strong talent for intimacy in cartooning to present situations — some personal, some fictional — that engulf the reader in such a way that the emotional content isn’t just being shared in the work, but experienced. It’s something she’s particularly adept at, along with presenting points of commonality between the emotional situations she portrays and the people reading them.

One of the books, Ghost Stories, is a collection of works that all revolve around the concept of loss and longing, but not in obvious ways.

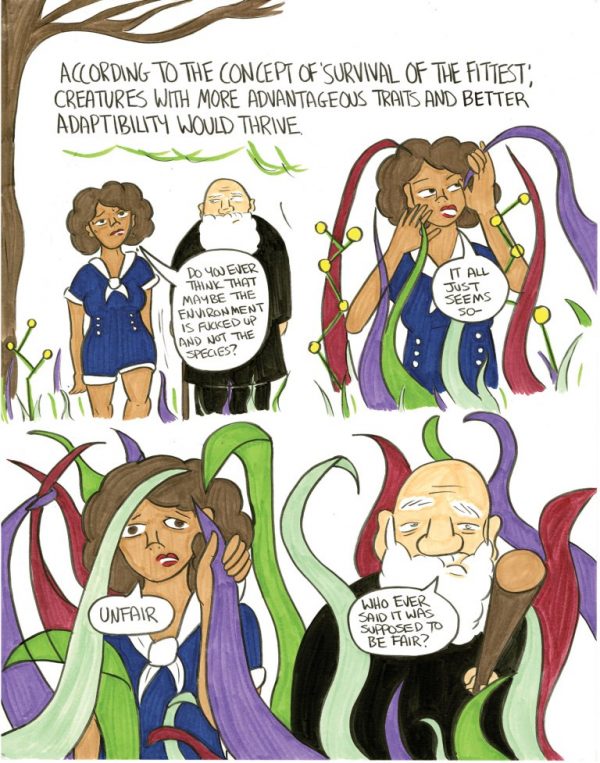

In the first story “Meet Your Idols,” Taylor mixes several elements to create a multi-faceted and personable work that creeps into some of her darker corners, while offering an honesty about those places as well as the brighter ones. Part of it is about facing her own personal trauma — that is, herself — and relating it directly, clearly, analytically. But to do so, she begins with conversational encounters with two of her heroes — Charles Darwin and Joseph Campbell.

That’s no accident. Darwin might have done more than anyone in history to explain the human condition in non-religious terms and Campbell has done the same regarding the human compulsion to tell stories. Taylor juxtaposes these interludes with some short fictional pieces revolving around concepts of loss, thus wrapping in all the aspects she’s included here, and then takes you on her personal journey.

It’s a very affecting piece, but what impressed me more is how Taylor doesn’t let the trauma control her presentation. It’s a testament to being a human, taking into account the aspects offered by Darwin and Campbell, and revealing the resiliency that can rest in any of us. Meet Your Idols doesn’t ignore the trauma, it doesn’t cast the trauma away as something unmentionable, but it doesn’t give up everything to it. Taylor is still able to collect all the aspects of her creative humanity to heal and to express that healing.

This is followed by “Wallpaper,” in which Taylor relates a period of her life by focusing mainly on aspects of interior design, specifically the wallpaper that comes in a new home her family has moved into, a comparison to other homes that she goes into, and different paint jobs that others choose and might be selected to replace the wallpaper. Taylor juxtaposes this with personal relationships, especially with her mother, father, brother, and grandmother, and covers the passing of time, the arrival of death, and the memories that linger.

With this story, Taylor veers away from the sequential and into an illustrated storybook format, with her narrative adorned on the opposite page by some form of design view of what she is describing. Sometimes it’s wallpaper, other times painted walls, but other times she expands the motif to the ground cover on an autumn day or a particular view in her grandmother’s kitchen or a display of watches for sale.

This takes you out of the action but adds a layer of mystery to each that you’re required to fill in, which makes it oddly more intimate. The design on the outside becomes a marker for the internal, sometimes as a representation of careful expression but other times through force of nature, flow of life, or just the practicality of presentation. It allows Taylor to express something abstract about these moments that neither words nor pictures with narrative intent can capture, and it strings it all together into a poetic, delicate remembrance.

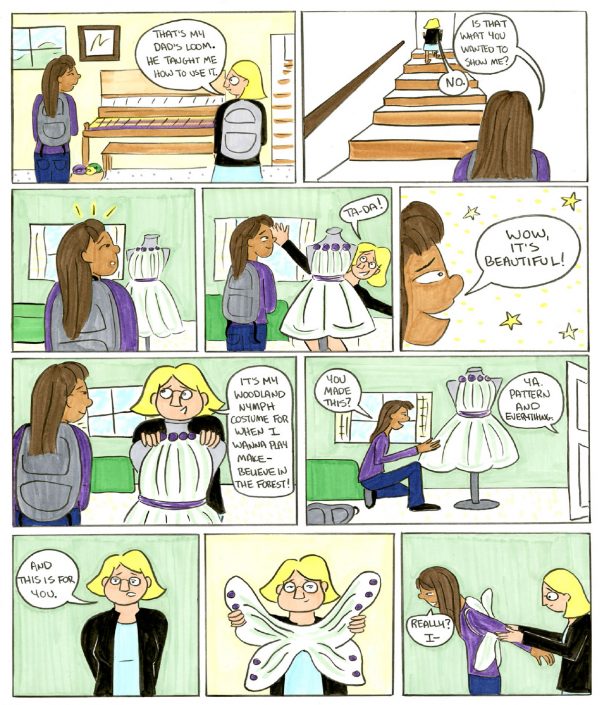

“Makers,” the last story in the collection, takes the idea of loss as a part of change, and the examination of the empty space loss can leave next to you and places it in stricter narrative terms than the other two stories. Tessa and Hope bond in high school over art and their drive to create it, and Makers traces their relationship long past the point it is over, and Hope truly becomes a ghost that occasionally haunts Tessa.

It’s interesting that in telling the story of the friendship, it becomes entirely about Tessa’s reading of Hope’s life, shedding light on her family situation, her personal goals, her boyfriend, her college friends, but no equal time is spent unveiling Tessa’s intimate being. The idea that you lose touch with friends is not a particularly unique one, but the examination of how certain people can engulf your concerns and nip at your ass even after they dissipate into your personal history is a perceptive vantage point to look at a friendship that has drifted.

Taylor’s Fizzle #1 touches on similar concepts as Ghost Stories but throws the reader into a microscopic examination of someone who’s coping with ghosts past, present, and future. Claire works as a barista in a tea cafe with little enthusiasm and has an amiable but less-than-dynamic live-in relationship with her boyfriend, Andy. Something is missing, and in this first issue, Taylor is less taking us on an exploration of what that something is and more setting the tone for what will follow.

As with Ghost Stories, Taylor is suggesting that nothing can make you feel more lost than the focus of other people. Some people are just on a track, they have a drive, and it’s disconcerting when you are someone who either hasn’t discovered their own path or has discovered no path and settled for practical measures.

Claire’s boyfriend mostly does drugs and complain about his family, but at least he has something that defines him reliably. It’s not enough for Claire, though she also butts heads with her manager, a tea barista with motivation and enthusiasm that fails to inspire her. And so Claire has the big empty space following her around like a ghost and the inability to fill that space into something helpful.

I don’t know where Fizzle is going, but Taylor is skilled at presenting the drudgery and small moments that add up to broader issues, and in capturing the negative spaces that are splotched around everyone’s souls, so I’m looking forward to following Claire’s story.

Comments are closed.