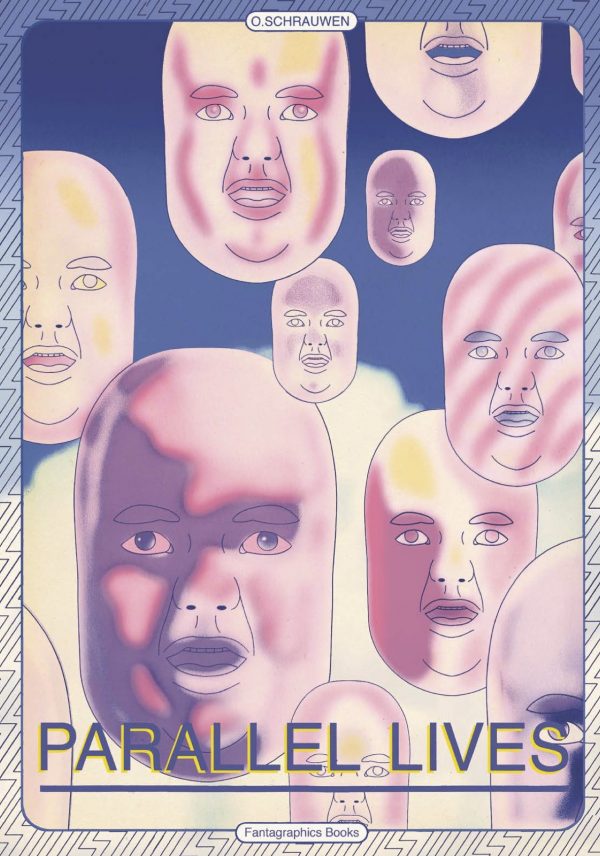

In Parallel Lives, Belgian cartoonist Olivier Schrauwen presents multiple versions of himself across the space-time continuum and well into dimensions that are untraceable in any normal sense, and he does so in a delivery that is decidedly singular. There’s no one else making comics like Schrauwen, and any given story is like an absurd deep dive into the universe of the cartoonist’s mind, where the fantastic collides with the casual, and the timing and observation of storytelling work along with a completely alien structure.

“Greys” is a recounting of an abduction experience, presented as a firsthand account byO. Schrauwen in order to make some sense of his experience. In many ways, its a recounting of any number of abduction stories you could read, presented with the same sense that because it sounds like all the others then that must give it veracity, right? Right? Well, no, but what it does do is create a shared mythology that provides comfort for some people while offering others a springboard for their own individuality.

That’s where O. Schrauwen’s narrative comes into place, where at first he is the object of the typical strange sexual medical experiment fantasy that so many people relate their experience as, but this soon turns into an exercise in philosophy fulfillment, where Schrauwen’s view of human history is validated by a surreal alien tour through the same. But this validation is the common way religious epiphanies are received, in that wider views of things beyond our knowledge either wholly support or entirely contradict what we already feel we know and provide such an intense emotional experience that we embrace it as the truth.

Leastwise, Schrauwen’s recounting is so bizarrely matter-of-fact and unadorned with any clever twists that it comes off as pretty creepy, like a story about an encounter with Bigfoot when you’re a kid in the 1970s. Something about the familiarity and the earnestness is unsettling.

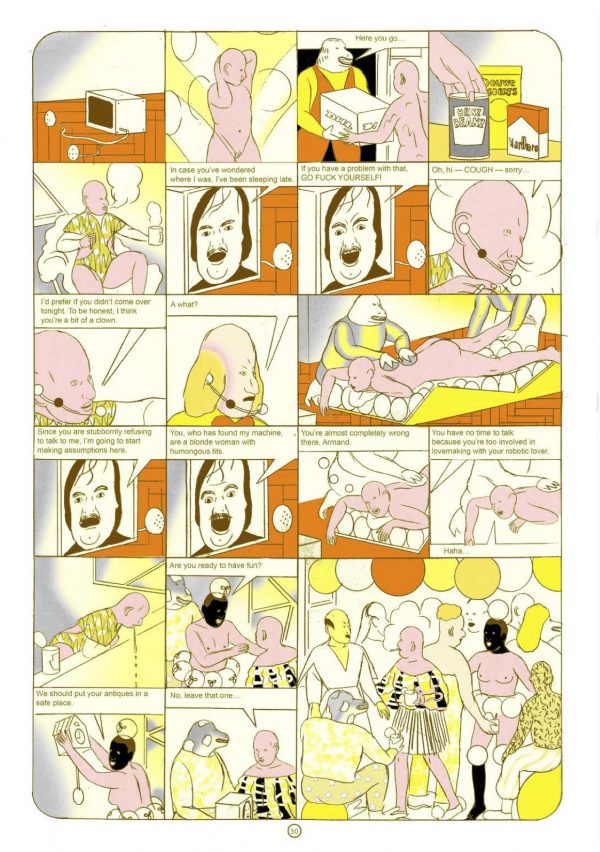

In “Hello,” Armand Schrauwen, a collector of antiques, comes upon a monitor that receives transmissions from an inventor from the past, but the collector doesn’t really know what to make of it, so goes about its future life while the inventor from the past gets irritated that no one pays attention to him. The way Schrauwen the cartoonist fashions Schrauwen the inventor’s behavior, though, it’s really like someone messaging a woman in the present and being frustrated when she doesn’t play along with whatever game he is proposing. The future people have their own game, though, and inventor can’t even conceive of it. Parable? Fable? Cautionary tale? Comeuppance? Take your pick.

The third story presents a neurological app called Cartoonify that turns a person’s perceptions into cartoons. Things become simpler, easier to do, the world becomes more two-dimensional. While a person’s experience during cartoonification might be satisfying to the person, it’s less so to the people who encounter the person. For instance, when Oly has sex with his girlfriend he is satisfied but she is left feeling like a balloon animal. It reminds me of the degree to which superhero action films are animated to the degree that if your eyes are not attuned to the computer animation used in the action scenes — which they wouldn’t be if you’re not an avid gamer — then the scenes look like simplified reality in your perception. They just look wrong, part of a shared illusion brought on by visual and perceptual grooming. In context of this story, being cartoonified proves unfulfilling.

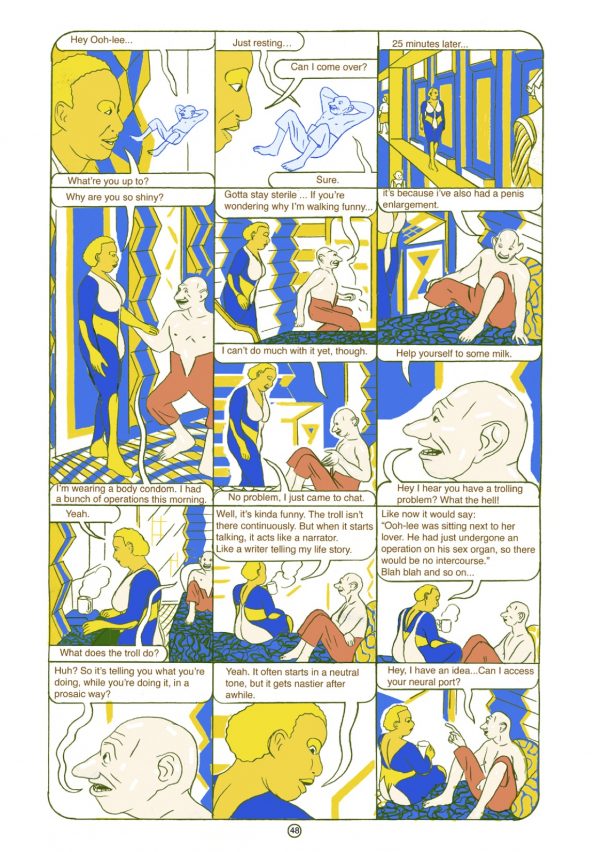

“The Scatman” focuses on Ooh-lee, who lives in a future when the forms of networks we currently use on computers have become neurological and Ooh-lee finds herself stricken with a voice in her head that she is convinced is a troll, much like one we would encounter on a social network. In her brain, though, the troll is inescapable, and his tactic is to narrate her life as if she were fictional. This leads to a number of stated observations that prevent Ooh-lee from taking any stance of willful ignorance about anything in her life, and this constant facing of the unbearable truths are wearing her down. Is the troll cartoonist Schrauwen? Or someone like Armand Schrauwen, speaking from the past? Or is it someone in a story we have yet to read?

“Mister Yellow” packs a tale of paranoia and fear that eventually goes well into two pages with 70 panels on each page. Olver keeps encountering a man in yellow that he calls the Yellow Man, and who, Olver becomes convinced, is out to get him in myriad ways. Faced with the irrationality of his encounters with the man, and suspicions regarding his wife, Olver keeps it to himself, and the situation careens out of control before coming to a mysterious, but mostly happy ending that seems to be asking whether there is a plan rather than randomness and, if there is, are we even equipped to connect the dots in a coherent way? Should we just maybe let things unfold and not torture ourselves?

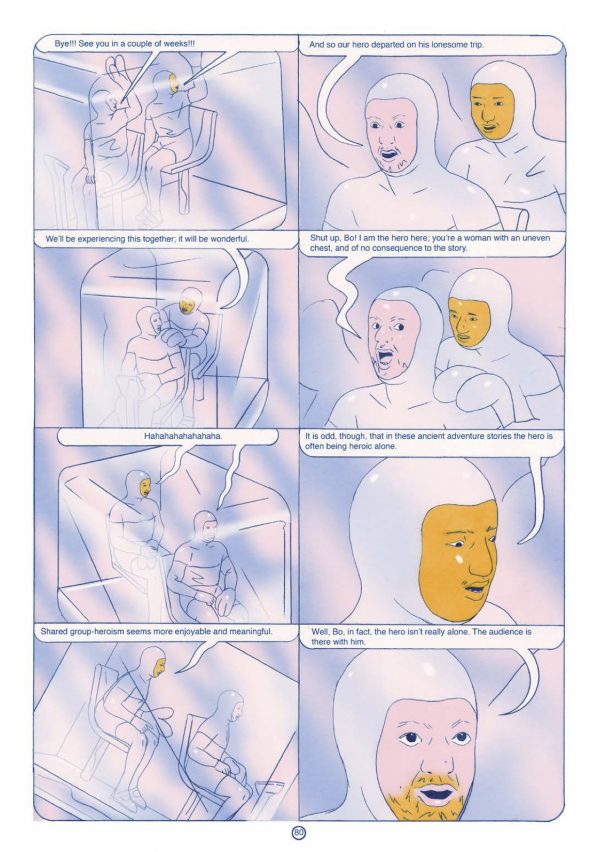

In “Space Bodies” a group of beings who have become all-knowing and left behind their physical form decide they want their humanity back. Olivier Schrauwen is one of them. Well, not the being, but the body the being inhabits, and Olivier’s first course of action is to rediscover storytelling while addressing people in the past. Amusement between Olivier and his companion Bo ensues as they begin to skewer the curious affectations of human storytelling, as well as sexual practices and gender roles. The bodies are a novelty and so are the results of having bodies as expressed through stories, but having a physical presence also gives them the opportunity to enjoy the wonders of exploration as they descend on a planet for study purposes. Physical presence also brings about the possibility of danger, which is something they have lost the feeling of and don’t quite know how to react to and sets them on a path of biological rediscovery hinting that origin might be destiny.

But this last story also connects back to an earlier one that brings everything full circle and offers some sort of coherency to the experience, though it’s difficult to say what sort of coherency. At the very least, it all makes an internal sort of sense and that has to do with the state of being human. Throughout the book, Schrauwen evokes such diverse visual elements as Steve Ditko, Jack Chick, and French animator René Laloux, as he explores his own versions of the big picture territory they also mined.

Schrauwen’s book is not separate accounts of various realities, but instances of realities interacting and seemingly creating a smooth continuity throughout all the disjointed points in space-time. It’s all connected, but it may not all be connected together one thing that we can see. Even in revealing the pathways and offering glimpses of the whole, the multiverse is still pretty mysterious, and Schrauwen is the perfect cartoonist to evoke that. It’s a triumph of a fourth-dimensional narrative being mashed into a third-dimensional delivery system.

Whoa, this one goes on my Comixology wishlist. Thanks John, and happy new year.

Comments are closed.