“You went when it was cool,” I tell her, “It was already starting to go corporate by the time I was graduating.”

“You know what’s weird is that when I was there, everybody was like, ‘You just missed it, you just missed it,” Nocenti muses. “Everyone was like, ‘Oh, you just missed the party.'”

One of the parties she certainly didn’t miss was the much-loved Marvel bullpen of the 1980’s. During her tenure, Nocenti’s run on titles like Daredevil saw the creation of seminal villain Typhoid Mary. She co-created Longshot with Art Adams, and edited countless issues of Uncanny X-Men and New Mutants. And that’s before we get into her work for DC.

Nocenti stepped away from comics in the mid-90s, turning her hand to editing work for High Times: “Vaporize in the afternoon…now let’s put a magazine out,” racking up credits at The Nation, Details, and Counterpunch among others.

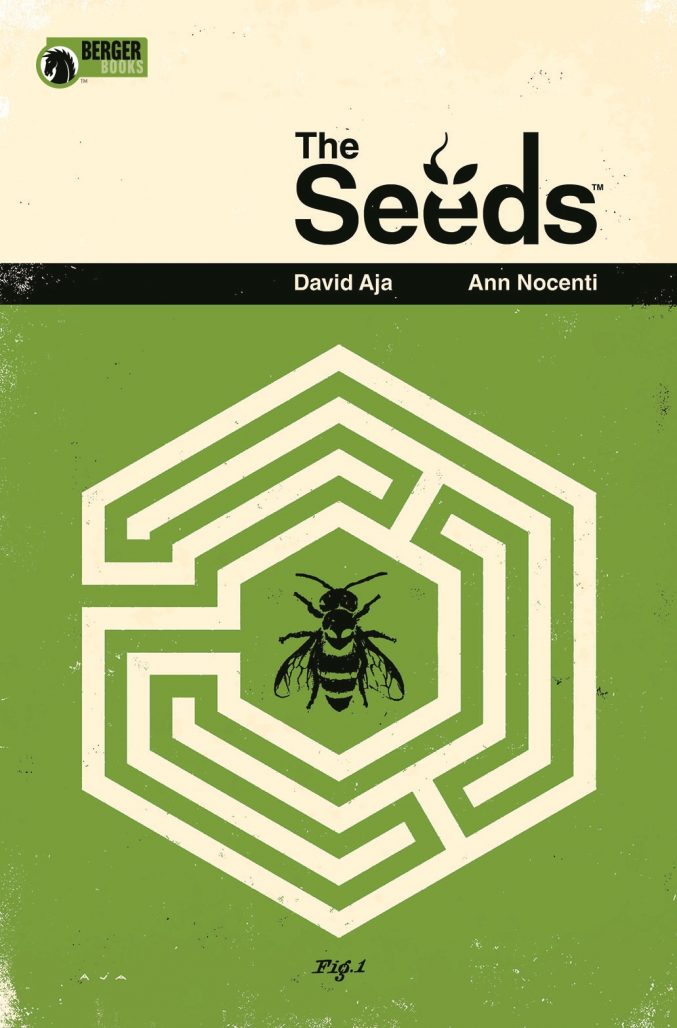

She’s periodically returned to comics, and next year she’s poised to join another influential comic party: launching the sci-fi political thriller The Seeds with artist David Aja for the Dark Horses’ newly minted Berger Books imprint.

Edie Nugent: I actually saw you and Karen Berger chatting after MOCCA last year…had Berger Books been born at that point?

Ann Nocenti: Yes, we were carrying a little secret around with us…I think your spidey sense was picking something up. We had decided to work together, but it hadn’t been announced yet.

I think Karen Green posted a picture on social media of me and Karen, and they were like ‘why are those two together for?’ You know, ’cause I’m like the Marvel girl, she’s the DC girl.

Nugent: You’re crossing the streams, what’s going on here?

Nocenti: Yeah, they’re not allowed to cross streams.

Nugent: You’re getting your chocolate in my peanut butter.

Nocenti: Yes, dammit.

Nugent: Do you think Berger Books would have happened or 20 years ago? I mean obviously you guys were both huge heavyweights, but would there have been the support?

The commercial recognition of her as an entity?

Nocenti: Yeah. Very interesting question…Karen and I were talking about this the other day. We were talking about how people always ask us, ‘was there sexism back then?’ What’s strange is that there were so few girls in the industry, that it was the opposite of sexism, I think. You know, I had Archie Goodwin and Denny O’Neill coming into my office talking to me about story–asking me if I wanted to write a story.

I had, you know, Larry Hama, Al Milgrom, he had all these wonderful men in comics.They were all really encouraging. Ralph Macchio gave me the Daredevil to write. Denny gave me my first story, and they were extremely encouraging of the idea that a woman wanted to make comics…even the idea that a female wanted to write Daredevil.

Nugent: So you felt industry support. Going all the way back.

Nocenti: I wouldn’t call it industry support so much as it was bullpen support. This is pre-Internet So everyone was right there in the office. I was mentored by Louise Simonson, who basically taught me everything. Across the hall, you had Jo Duffy writing Star Wars, and then in the bullpen, we had Marie Severin…a powerhouse. So between me and Marie’s generation, we did have sexism. I mean she did so much in the industry and in the business, and she’s kind of unrecognized.

She was right there on staff doing sketches when they needed them and covers when they needed them. So her generation–I think there was maybe more sexism than in the ’80s, ’cause you’re talking a post-’60s, ’70s culture, post-women’s liberation, you know, and so we were encouraged.

I probably I felt more sexism when I came back to comics at DC and I was working with Gotham, in the Bat family. All those guys [at DC] individually are really nice, but it definitely felt like a boy’s club.

Nugent: Just sort of a pervasive feeling?

Nocenti: Just a pervasive feeling that it was like a young boy’s club, and you were the token female, you know? I felt it more in 2012 when I came back to comics.

Nugent: This is when you were working on Catwoman?

Nocenti: Yeah, Bob Harris, Dan DiDio, they were wonderful, and individually everybody seems supportive, but you couldn’t help but to feel that you were running with a pack of wolves. You know, it was like a bro pack. You’re running along in the bro pack, and they were all being very nice to you, but it felt …

Nugent: There was a shift in tone?

Nocenti: Yeah. It was a little bit different. You didn’t feel like you were being mentored, you felt like you were being tolerated. Whereas in the ’80s, you felt like you were being mentored.

Nugent: Did you notice more of a community atmosphere in the ’80s in general in how comics were made? Than in your modern experiences.

Nocenti: Oh yeah, absolutely.I think that’s also a function of how everyone had to go to the bullpen to drop off work. There’s no Internet, you know, so we’re all …

Nugent: It’s not fragmented. By design it has to be communal.

Nocenti: Everybody’s there, and everybody had studios either in New York or in Connecticut or Pennsylvania, and so you’d come in to drop off work. Yes, we used mail, but if something was late, you had to bring it in, and then that was the chance for all the artists, you know, Frank Miller, Walt Simonson, Steve Ditko…they’re really running into each other in the bullpen, hanging out, showing each other pages. It was amazing. I mean you know–Dean [Haspiel] has some of that with the Hang Dai [studio] probably.

Nugent: The convivial atmosphere, inspiring each other, sort of water cooler thing?

Nocenti: Exactly. Yeah, and you know, the advent of the movies changed everything. The money comes in and then you can’t really go up to DC and Marvel and just hang out. You need like a pass and they take you right to the office.

Nugent: When you’re looking back on some of the characters you’ve worked on or created over the years, like all your stuff from New Mutants, which personally I love so, so very much, and Typhoid Mary, has your perspective on them changed at all?

Nocenti: Well I think you can’t help but to do that. I mean, certainly the Longshot series with Mojo and Spiral and the Mojoverse to me looks more like Trump. You know, reality shows and media. So it’s sort of like I look back on that, and I say, well that kind of finally makes sense to me, when it seemed incoherent when I was writing it.

The Daredevil run I’m pretty proud of, because I think that it was like … I approached that very much like a way I later approached documentary film, which is just journalism. You let the world in. You hit the streets and you let the world in. I lived in New York, and you could go to Hell’s Kitchen, and just see what’s going on.

Nugent: Immerse yourself.

Nocenti: Yeah! There’s a bunch of little kids on a skateboards, and you’re like, ‘why are they out of school? Why aren’t they in school?’ Then you go, ‘let me put them in a comic.’ It’s sort of that whole documentary thing. I always had a problem with the escalation narrative of comics, where you have no choice but to have everything escalate to a fight. Actually, The Seeds is gonna be the first thing I’ve ever done that didn’t have to escalate to a fight.

Nugent: Let’s talk The Seeds. Very little has been released about it yet, so what can you share with us?

Nocenti: Well originally, we had done a version that was like an homage to ’50s tabloids. I always loved those. The idea was you would be presented with a tabloid cover, and you would not know which stories in the issue were true and which ones weren’t true. We worked on that for a couple years, and then Trump got elected and the fake news thing happened, and we kind of sank into a depression and thought, ‘you know, oh shit, we can no longer do this story, because now it’s real life.’

We ended up like trying to pull out what we still loved, and take it from being this really complicated, you know, satire of journalism, and make it just more of a human story. So what we did was we end up retaining one of the tabloid stories, which was kind of like this alien/human love nest. So the alien/human love nest tabloid story is now kind of like the real story.

Nugent: Is that how you see this administration? Alien/human love nest?

Nocenti: Oh no. That part of the story is a little bit more about gender ambiguity. So you know, race, sex, gender, all the things that people are trying to keep in boxes, we want to take it all out of the boxes.

Then the journalist stumbles on the love nest, and it becomes this sort of–you as a journalist understand that oh, we’re having a nice chat here, but then I gave you something really like dirty and spicy you’d like to print…then you have to figure it out. ‘Can I put it in, and piss her off, and then what happens to my career, will anybody ever talk to me again?’

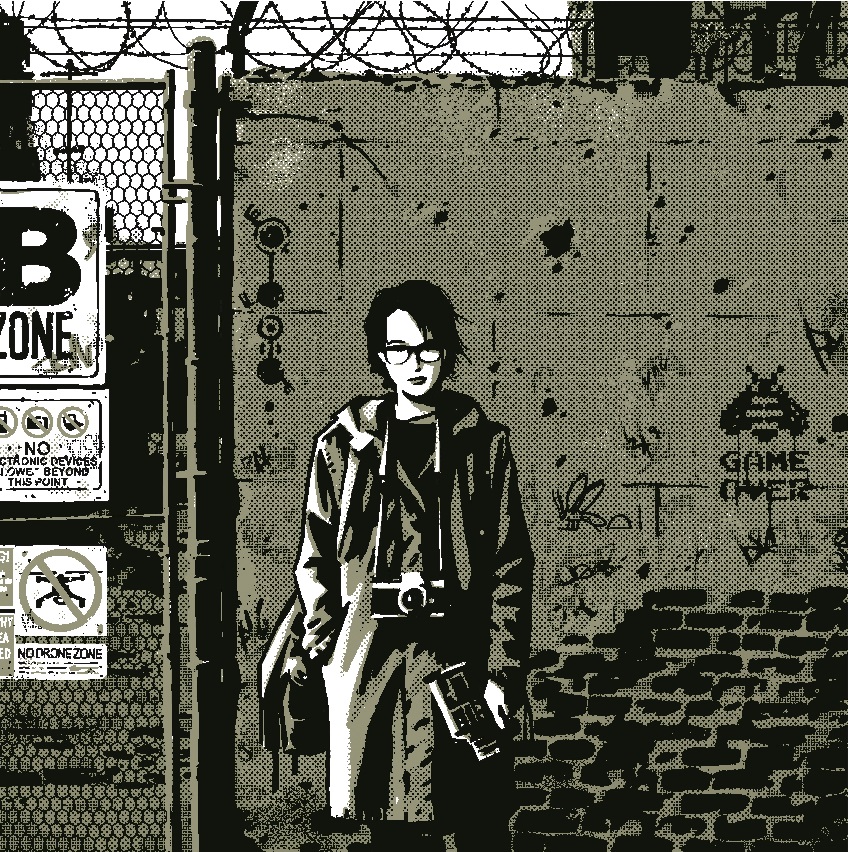

So all those things that journalists go through are in this comic. So that’s Astra, she’s sort of learning the profession through uncovering these mysteries. At the same time, the earth is dead, and you know, we killed it, but people are still hanging in there, because people still hang in there even when everything’s dead. The planet’s dead, but everybody’s still having fun. It’s not a dystopian, it’s almost a utopia.

Nugent: A utopian dystopia?

Nocenti: Yeah, utopian dystopia. Say that three times fast.

Nugent: I can’t. You’ve not shied away from addressing political themes in your work in general. I wonder what you thought are the some of the different roles art can play when the government is like particularly jingoistic?

Nocenti: I worked on a street art museum for a year and become sort of educated about how you can know a lot of a city by what’s written on the walls. If you enter a city and you look around and there’s no graffiti, that tells you something about how the government is white-washing everything. You see like little messages on the wall, we call it like the newspaper of the poor. People sending each other messages, so we’re doing stuff with graffiti, which David is putting in the art.

David Aja raises the conversation about comics with everything he does. He always does something that lifts the linguistics, the marriage of words and pictures. He lifts the conversation someplace new.

Nugent: Did you request him specifically, or, as an artist when you were developing this?

Nocenti: We did a Daredevil together. Then we stayed in touch and wanted to work together, and I think it was just sort of a happy accident that I left DC and was doing this street art museum–just after he did Hawkeye. I think he got under this thing that artists can get into where it’s just easy to keep doing covers.

You kind of get into this thing where you haven’t been telling stories for a while, and if you’re someone like him who really wants to tell stories…and me, I really didn’t want to do another superhero. I think it was a happy accident.

Nugent: It was famously said by Jack Kirby: ‘Comics willl break your heart.’ You diversified into film and magazine editing, which you mentioned, but you keep returning to comics. So what draws you back?

Nocenti: Well, comics are my first love. I would say it’s my first love. There’s something maddening about comics, in that it is so hard to get the balance of even a single panel perfect. Just the perfect amount of words that go with the art, that lift it someplace else. When you’re doing superhero stuff, you’re always late, you’re always behind, and you can’t really … you’re too damn tired.

But be able to craft that beautiful balance–that’s why I keep returning, because I can’t seem to get it right. I remember shining moments, like the Daredevil I did with David Aja…the stories with Art, there were moments when I felt it.

Then you go off and you do other things and then you go, “Wait a minute,” you know, it wasn’t good enough. You know?

Nugent: So it appeals to the perfectionist in you?

Nocenti: It’s more like it’s an ongoing conversation.The marriage of words and pictures, and then the whole page– the rhythm of the whole thing, it’s just a really difficult, comics, people have no idea how hard they are. They look easy, but they’re not. I think everybody in the business–writers and artists–we’re trying desperately to get it right.

Can’t wait.

I’ll read this. Nocenti’s Daredevil run was the best after Frank Miller’s. Can’t recommend it highly enough. (It also had the best art of John Romita Jr.’s career.)

If the industry had more Nocentis, I might not have given up on corporate comics in the ’90s.

Ann is a legend. I’ve been a fan since her New Mutants and Daredevil runs when I was a kid. Every word of this interview is gold. Thank you Edie and Heidi!

Could not be more excited about this book ! Thanks Edie for such a great interview

With havin so much content and articles do you ever run into any issues of plagorism or copyright infringement?

My blog has a lot of exclusive content I’ve either

authored myself or outsourced but it seems a lot of

it is popping it up all over the internet without my agreement.

Do you know any methods to help prevent content from being ripped off?

I’d definitely appreciate it.

Interesting to read Nocenti’s comments about the relative lack of sexism at Marvel in the ’80s, and the encouragement she received from men in the Bullpen. And her feeling that DC in 2012 was MORE of a boys club. Does this say something about the industry’s deterioration, at least at the Big Two?

I do remember guys in comic shops, in the late ’80s and early ’90s, saying they wouldn’t read Daredevil as long as a “girl” was writing it. Never understood that mentality. If the writing is good, who cares about the writer’s gender? Ann’s Daredevil writing was very, very good. It holds up today, despite some topical references that may need to be explained to young readers today.

I think it says a lot about the different corporate cultures of Marvel and DC from the 80s on.

Comments are closed.