by Alex Dueben

Anders Nilsen is a hard artist to describe. He’s a cartoonist and illustrator who is interested in narrative and the formal aspects of comics and finding a way to tell stories that push what comics are in different ways. Big Questions was an epic tale about life and existence centering around a number of birds in a landscape that resembled the upper Midwestern plains. Don’t Go Where I Can’t Follow was a scrapbook detailing his relationship with his fiancée, the late Cheryl Weaver. His last book Rage of Poseidon was a fold out book with text and illustrations.

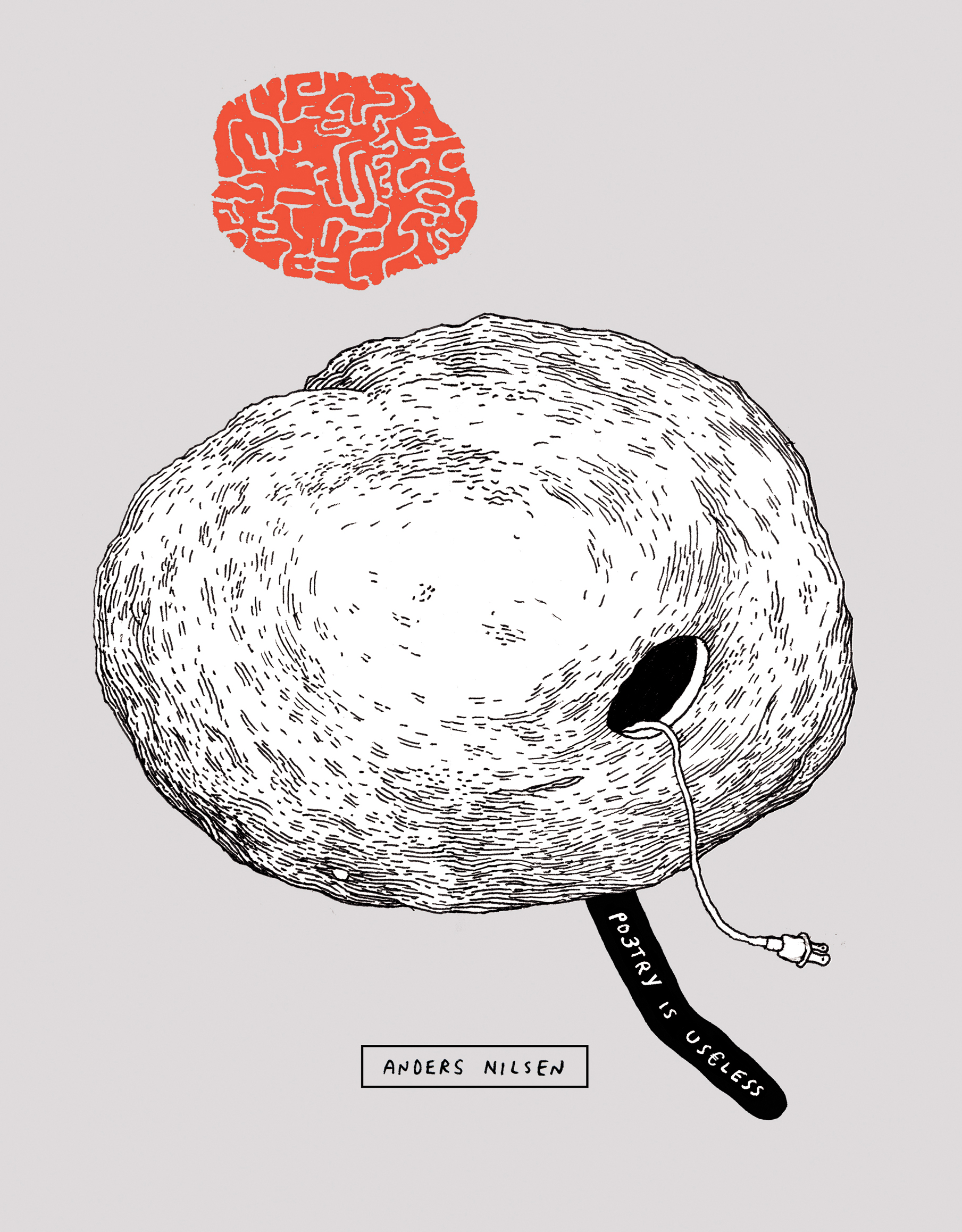

His new book is Poetry is Useless. The book reproduces pages from Nilsen’s sketchbooks and the result is an experience that Nilsen compares to a poetry collection. Like his other books, it uses words and pictures, there are narratives, and yet, they’re not exactly comics. Like his best work though Poetry is Useless is a brilliant meditation on life and art and the world. We spoke recently by phone about what the book is, what it means and how everything he does is drawing.

Alex Dueben: So why is poetry useless?

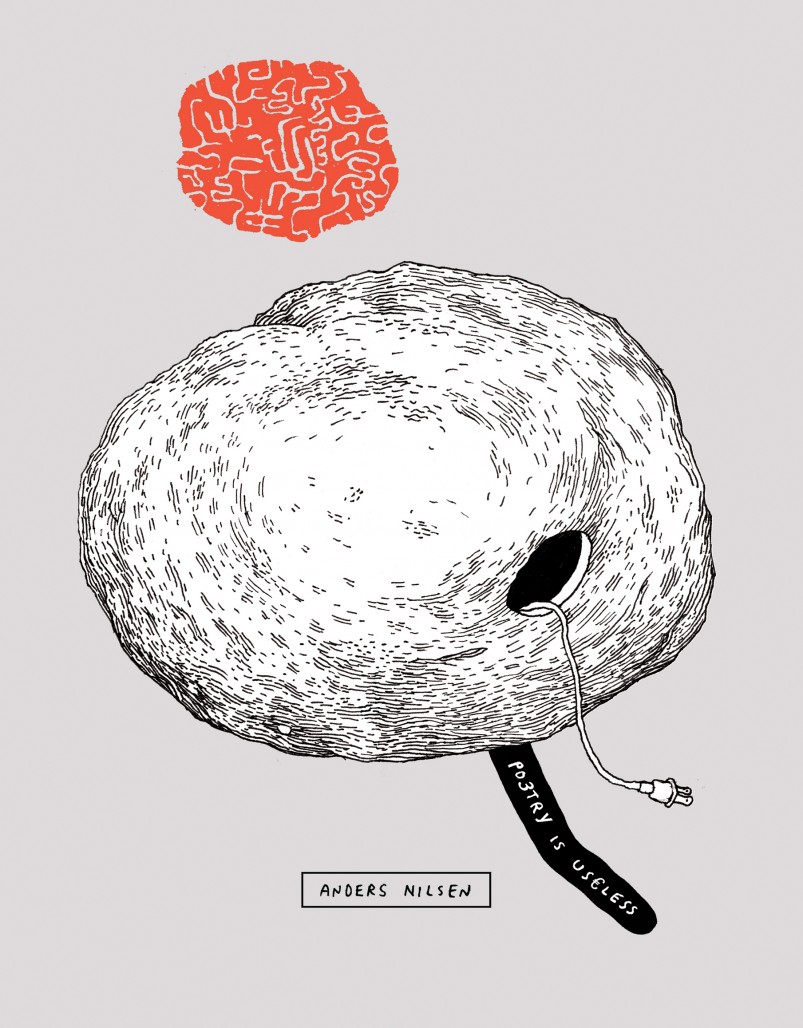

Anders Nilsen: [laughs] I don’t know if it is useless. The title says that, but I don’t know if we should trust titles to come to conclusions about actual things in the world. The title comes from a piece in the book. I can’t really give it away. I can’t give the answer to all the riddles or nobody’s going to buy my book.

Dueben: The title comes from a line uttered by a shadowy figure who may or may not be you who keeps popping in and out of the book.

Nilsen: There are plenty of senses in which one might make an argument that Poetry is Useless. There’s a long tradition of art theory talking about the reason that art is important is precisely because it’s useless in some sense. Which…I don’t believe. So, that’s one answer I’ll cross off the list for the inquisitive reader.

I sort of think of this book as my poetry collection. If it’s useless then it’s a self-criticism. I encourage people to read the book and come up with their own take.

Dueben: It’s hard to explain what the book is without reading it because the book is the totality of the book.

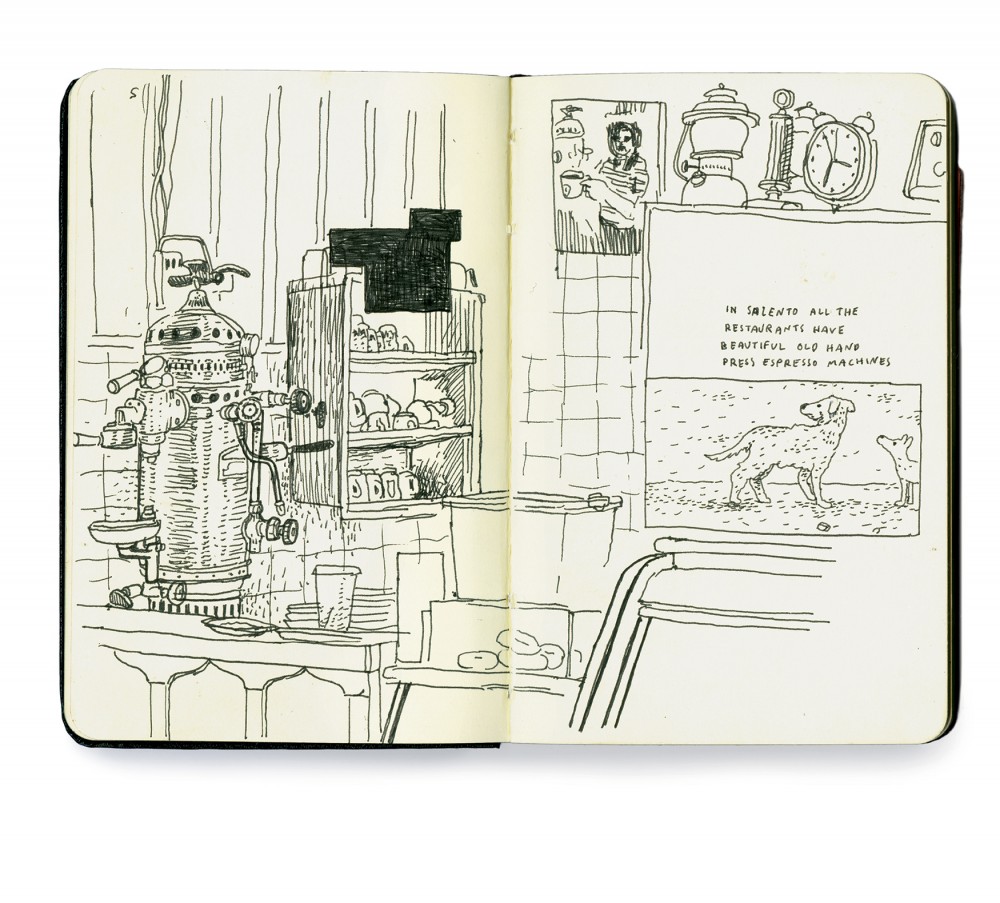

Nilsen: That’s fair. On it’s face it’s a sketchbook collection, but in a way it’s really not. The idea of a sketchbook collection is that you’re peeking behind the curtain. You’re getting to see the artist’s pure process, but all the work in here was done with the audience in mind. It was all stuff that was intended to go on my blog immediately and be part of that internet conversation. In that sense it’s not some pure insider sketchbook experience. It’s all short pieces that aren’t necessarily connected in any explicit way. There are themes that follow through the book and there are also short travelogues and memoir-ish pieces as well. If I have a couple graphic novels and I have some graphic short story collections and graphic memoirs, to the extent that there are equivalences, this is my graphic poetry collection.

Dueben: Talk about this idea of a sketchbook that you’re intending for people to read as opposed to what people think of as a sketchbook, which is just random drawings.

Nilsen: In a way, I think the artist’s sketchbook collection is a fake idea. It’s attached to the idea of the ‘pure’ artist and ‘pure’ expression, which is stuff I think is nonsense and pointless. I think every artist who’s working in their private sketchbook secretly in the back of their heads hopes that someone will look at it and read it and discover their true genius. We are social creatures so there’s a sense in which everything we do is a little bit part of that social context, whether we think about it or not. Or admit it or not. There’s a way in which I’m taking that idea and just making it part of my process. There is one sense of what a sketchbook is where you’re practicing drawing or trying out ideas and that’s a little bit of a different animal. For me, I just have this little book in my back pocket all the time for whenever I get an idea or whenever I’m bored or on an airplane and don’t have anything to do. The sketchbook format is more just a format of convenience, always having a blank piece of paper to play with ideas or work out thoughts.

Dueben: To what degree is this a curated volume?

Nilsen: That’s the other thing about sketchbook collections. There is this sense that you’re getting a peak behind the curtain and you’re just rummaging through an artist’s actual sketchbook. But they’re always curated in some way. They’re giving you this slightly false sense of being on the inside of the process. A lot of the material that I do in these books is terrible and it doesn’t add up to anything, so it doesn’t get put up on my blog. Of the stuff that got put up on my blog I think originally I had 400 or 450 spreads that I was thinking about using. It got edited down to 225 or whatever it is. That made it a much stronger book. The material that’s in there is the best of the lot. There’s a lot of crap I’ve done that the reader doesn’t get to see. [laughs] It’s very different than if I’m hanging out with a friend – a lot of times if cartoonists are hanging out and drawing and you might just hand over your sketchbook for people to look at, and that’s different. In that case they are getting the nuts and bolts and the stuff that’s not working and the stuff that’s just exercise.

Dueben: You’ve been putting these sketches online for years. Why did you start?

Nilsen: I think it was 2001 that the Holy Consumption started. Jeff Brown, John Hankiewicz and Paul Hornschemeier and I all started this website together. Paul provided the impetus for that. There was a weekly sketchbook section where we could put up whatever we were working on. I started posting pages from my sketchbook or scraps from my process. That’s just how I thought about it for a while, just giving the readers or fans a little bit of an inside look at our process.

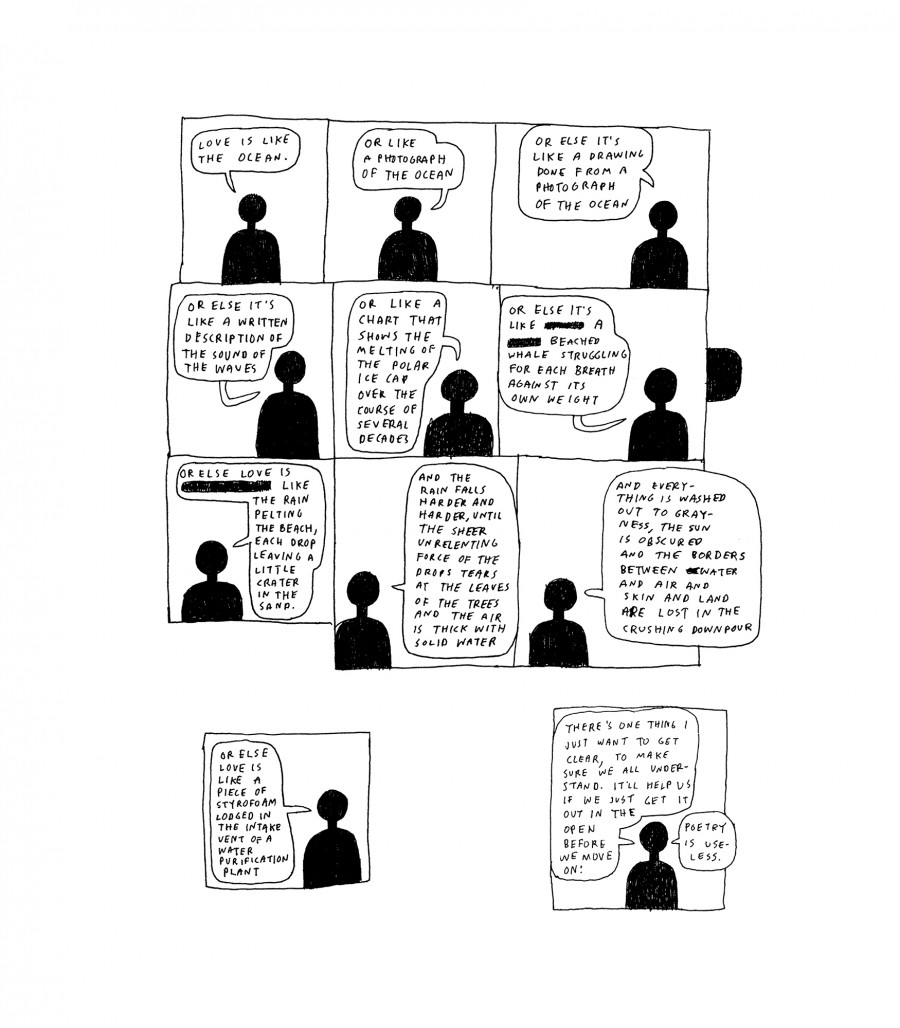

The very first strips with this blank head talking came out of a trip in 2007. I was in Lucerne, Switzerland for Fumetto – there was a show of art from Kramers Ergot that year so Sammy Harkham, CF and I were there. We didn’t have that much to do so there was a lot of sitting around drinking coffee and drawing and talking. I started making these little strips out of snippets of our conversations. Something just grabbed me about this format of the blank face saying inexplicable weird things.

Dueben: What was it about the blank face? We’ve spoken in the past about Tintin and the way that you used animals in Big Questions and how people are able to project themselves onto these blank characters.

Nilsen: I think this particular blacked out blank face does that, but is also a bit of a wall so it invites identification on the one hand and repels it at the same time. There is something confrontational about it. For a long time I would do these strips where this blank face is talking and part of me wondered, what’s the point of this? Maybe these should just be prose pieces. Maybe I don’t need to do them as comics. But the fact is that it does change it in a certain way when you depict the person talking. You lose that sense that prose carries of a disembodied, omnipotent narrator–or the sense that it is in fact the writer talking to you in a kind of intimate way. Those pieces feel like it’s me talking and yet it’s coming out of this weird character that doesn’t have a face so it undermines that sense at the same time. I like that push and pull.

Dueben: There’s a line on your blog that everything you do is drawing. What do you mean by that?

Nilsen: As an artist I do some drawing, I do some painting, I do writing, I draw comics, I tell stories, I do illustration… I tell stories in very different kinds of ways. I make traditional comics and then I also do weird experimental stuff. Even though I’m working in all these different modes, the thing that I think unites them all in some way is that there’s an element of drawing. There’s a traditional dichotomy between drawing and painting in fine art: drawing is about figuring out ideas and finding your way and learning and playing, whereas painting is a finished salable object. You could make a similar distinction in comics. In everything that I’m doing I’m exploring a little bit. Even constructed narratives like Dogs and Water and Big Questions, for me it’s very important to be constantly finding my way and to not really always be sure where I’m going or what the book is about until I get to the end. There’s always an element of exploration and finding the form of the story, which is what drawing is about. You don’t do the painting until you’ve figured out the form. In some ways that may be’s a little bit of a false dichotomy: good paintings are always going to have a little bit of openendedness and a highly constructed story, if it’s good, will always have some mysteriousness to it.

Dueben: There’s thinking involved in the act of drawing.

Nilsen: Yeah, and, crucially, paying attention. That’s the other thing. Observational drawing is very much about looking in a very immediate, existing-in-the-now way. You have to empty out your brain and your ideas about the world to get the contour of the person sitting in the cafe just exactly right. It’s really hard to do it and it’s super satisfying when you’re able to get it just right. Satisfying and surprising. That’s the other thing that’s important to me. Surprising myself a little bit–both with story and drawing.

Dueben: Do you have a routine with your sketchbooks? Do you draw every day?

Nilsen: No. I should draw every day. I would like to draw every day. [laughs] The truth is that I’m most prolific when I’m traveling. When I have this forced down-time of sitting on an airplane or sitting on a train or waiting for my talk to start. My normal life is pretty packed with answering emails, working on illustrations, working on books, sweeping the floor, brushing my teeth. [laughs] I don’t draw enough in my sketchbooks, I feel like, and I certainly don’t have a set routine.

Dueben: Writers often say that they’re making sense of the world through writing and reading Poetry is Useless, it felt like you making sense of the world and your feelings through drawing in a similar way.

Nilsen: I think that’s true. You don’t always know what you think about things. The piece about the conversation I had with the woman on the airplane, for example. After it happened it just felt like this odd, inexplicable, but powerful moment. It wasn’t until I actually sat down and drew out the conversation and the weird pauses that happened in between that it starts to feel like, oh, it means this, it connects to my other ideas about the world in this way.

Dueben: As part of that, readers can see this sense of play and figuring it out, rewriting, making corrections.

Nilsen: That’s what I mean about seeing an artist’s mind at work, you’re seeing me make mistakes and back up and start over and it’s like jazz. [laughs]

Dueben: When it doubt, compare art to jazz.

Nilsen: Yeah. [laughs]

Dueben: Each of your books is very different from each other. Is that a conscious choice on your part?

Nilsen: I don’t know. I am a cartoonist but it’s sort of just by accident that I’m a cartoonist. I studied painting and I’m interested in music and I do a little of this and I do a little of that. I ended up doing comics and found an audience for it, but I’m interested in other ways of telling stories and I’m interested in exploring the boundaries of how different mediums work. Rage of Poseidon wasn’t really comics in a way. It’s pictures and words and it’s telling stories with those two things, but it’s pretty different.

Poetry is Useless is comics–kind of. Some of it is comics, some of it is drawings, and some of it is telling stories in slightly different ways. The medium is the medium of the pocket sketchbook more than the medium of comics. It’s me figuring out if I take that on as a medium what is it capable of, what does it do well. That allows me to start playing around with things. Some of the drawings play with the use of the spine or the fact that it is a book, so… the turning of the page, stuff like that.

Don’t Go Where I Can’t Follow won an award as a graphic novel and there’s only 12 pages of comics in that whole book. But whatever. I’m interested in storytelling and pictures and what those two things make possible.

Dueben: Don’t Go Where I Can’t Follow and Rage of Poseidon seemed to be you saying, these are technically comics, but they aren’t comics.

Nilsen: Right. The definition breaks down. It’s really hard to define what comics is. It’s definitely a “you know it when you see it” kind of situation. I’m an artist that works with pictures and words and telling stories. I’m interested in books and reproduction. It’s by accident that I have been slotted into the comics world and the comics community. I’m happy that it exists for me to get slotted into, but I’m also happy to work outside it.

Dueben: Poetry is Useless similarly uses words and images but it uses the form of a sketchbook in a similar way that those books approached comics.

Nilsen: The book I’m working on now is definitely comics. [laughs] I’m doing an actual graphic novel that will be easily recognizable by everybody as part of the traditional comics form. It’s in its very early stages. It’s really been fun to work on and start a brand new story where I don’t know where it’s going. I have a lot of ideas swimming around. It grows partly out of a story in Rage of Poseidon about the titan Prometheus and this book is going to be largely about that character. It’s probably a little bit connected to Dogs and Water, too. The main character from Dogs and Water is going to make an appearance of some sort. It may or may not connect to the Sisyphus story I did in Kramers Ergot 4 back in 2003.

Dueben: When you start a narrative, is that how you typically work, find a starting point and discover it as you go along?

Nilsen: Actually this one’s a little bit different. Pretty much every book I’ve done has started as something small and unassuming in my sketchbooks. Big Questions started that way. Dogs and Water started that way. Poetry is Useless obviously. Rage of Poseidon. Pretty much everything started with me playing around with an idea and then the idea doesn’t want to let me go and I stay with it and eventually it turns into a book. This is different in that I have some ideas about character and plot and themes that I want to deal with. I’m doing a lot of reading and a lot of research. There’s stuff about human origins and human nature and the nature of language that I want to play with. I don’t know where I’m going to go, exactly, but I’m enjoying the early stages. It feels like it’s going to be a big long book. It’s going to all be in color, which I’ve never done for a whole book.

Dueben: You’ve done some short color projects, right?

Nilsen: I do color stuff for illustration work a fair amount. My piece in Kramers 7 was all painted in gouache. But yeah generally I haven’t painted or colored my comics, much.

Dueben: Have you started thinking about approach or material you’ll use to color it?

Nilsen: I’ve drawn 21 pages and I’m not a hundred per-cent sold on how it’s colored, but we’ll see. I wanted to paint it in gouache, but that’s proven to be too complicated and too much a pain in the ass. So, I’ll have to do it in photoshop but I want to do it in a way that feels organic and has some texture and warmth to it.

Dueben: Do you plan to serialize it?

Nilsen: I haven’t completely decided, but yeah. I think I am. It’s in the pretty early stages, though. I might change my mind next week. [laughs]