by Alex Dueben

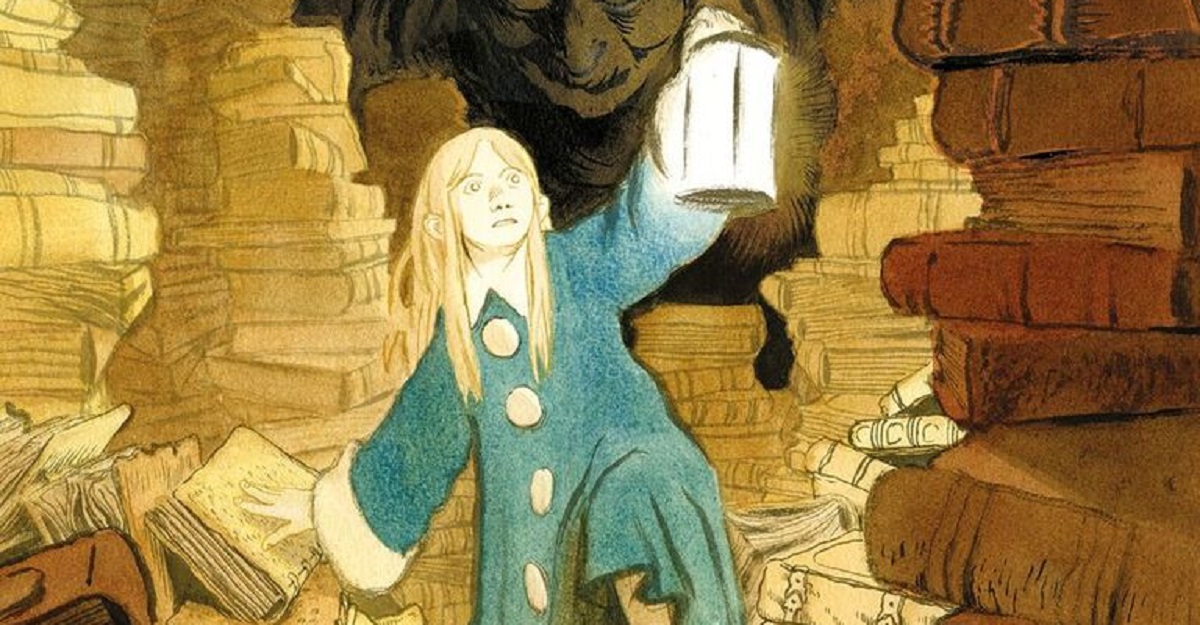

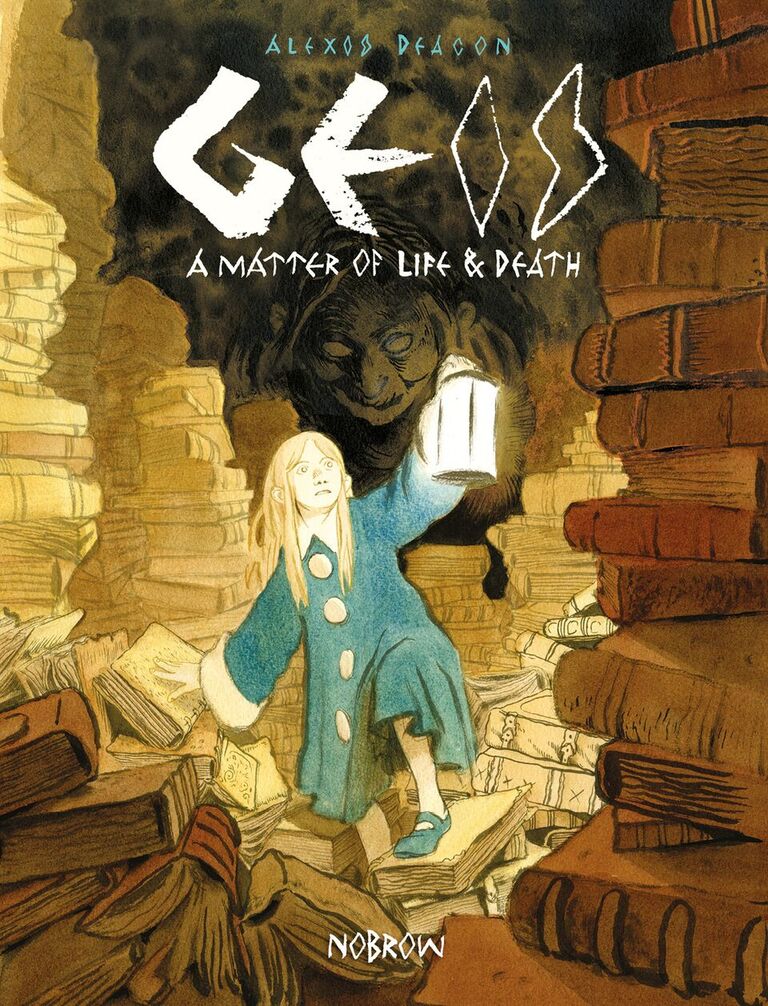

The heroine, Io, is a young woman who ends up witnessing the death of the king and becomes caught up in an elaborate magical plot that might kill her and dozens of others. Along the way, there’s a race as people flee to the castle before the sun rises, a pack of wolves, Io swooping in on a war kite with a crossbow, and questions about the nature of magic and life. The Comics Beat recently sat down with Deacon to discuss the fantastic saga.

Alex Dueben: What is a “geis”?

Alexis Deacon: I’d grown up with this book of Celtic mythology and folk tales and they very often used this concept of “geis.” The idea is that we all have these “geisa,” these rules we mustn’t break, but you don’t necessarily know what they are. You go to a priest or a wise woman and they would say, you must never speak to a woman wearing purple or you must never eat five peanuts consecutively or you must never jump over one black sheep and two red sheep. You go, okay, got it, no problem–but then you inevitably do all those things. There’s no way of escaping it. Often in the stories the more things they do to get away, the quicker they bring the events about. I really liked that idea of an inescapable fate. I don’t use it in exactly that way but the core is the same.

Dueben: As you say you use geis a little differently than it’s traditionally used. How do you describe the book?

Deacon: It’s tricky, isn’t it? [laughs] It’s a fantasy story inspired by folktales and fairy tales, but it’s an original work. I just think of it as a work of epic fantasy. It’s trying to be like the things that I loved when I was growing up. All the oddness and weirdness and not quite fitting in the genre comes from things that I think are normal, but other people go, what the heck is that? You know that feeling you have when you watch a David Lynch film. His concept was to offset all the weirdness and strangeness and badness in the world with beauty and goodness and purity and light, but the robin in Blue Velvet is actually scarier than anything else in the movie? [laughs]

Dueben: You have a lot of odd moments in the book which I really enjoy. The book clearly draws on a lot of fantasy stories but it has its own take on things. I’m thinking of the scene where some characters are running from wolves and another character swoops down on a kite with a crossbow. I did not see that coming.

Deacon: [laughs] It’s similar to The Usual Suspects where Kaiser Soze has one notice board to build his whole story from. I have all these ingredients around me that have become normal to me and I’m trying to collage them together into a classic tale. I really like that war kites are a thing and I was like, can I put war kites in the story somehow? I’m the writer, I’m putting war kites in it! No one says I can’t!

I’m very used to working in children’s picture books where you hear “you can’t do that” a lot. I think I’ve developed a writing style where I put things in almost so that the editors will go, “that’s weird, take that out,” and they won’t notice the thing that you really wanted in there. But here they just let me keep everything. [laughs]

Dueben: In the book’s acknowledgements, one of the people you thank is Isabel Greenberg, who is another cartoonist who likes to take classic stories and fables, and ends up crafting something new and different and unusual from those familiar elements.

Deacon: I really like her work. She has a new book coming out later this year, which I’ve been lucky enough to read. It’s really, really good! We helped each other in making these stories. She’s been a big help. I’ve come to rely on a lot of collaboration in the generative stages. Sharing the story with people that I know and trust and seeing what they get stuck on and what they react to and so on. I do a lot of testing in the early stages.

Dueben: Did you conceive of this as a trilogy of books from the beginning?

Deacon: Not from the very beginning, no. I realized that half way through writing book one. From then I had a synopsis in my head for books two and three, but I wrote and drew book two out in rough before doing the artwork for book one. Now I’m working on finishing book two and I’ve written and sketched book three in full. The story has an ending!

Dueben: It’s mentioned on the last page that Book Two will be called “a Game Without Rules,” which seems to contradict this idea that a geis is all about rules that can’t be broken.

Deacon: You can make of that what you will when you read it, but essentially I think I’m writing these books not to answer questions but to pose questions. A lot of the situations in the book are based on moral conundrums and choices that we make throughout our lives where I’m not sure what the answer is. The focus of the three books is really about the difference between using the energy of others to feed your own ambitions and desires, and giving your own energy to feed the ambitions and desires of others. And the consequences of both of those ways of approaching life. I have a friend who’s very successful and their success is built on other people investing in their dream and giving their life’s energy in support of that dream. He’s achieved some really wonderful things. I just couldn’t be that person. I couldn’t allow other people to live through my dreams–and I don’t know if that’s a strength or a weakness.

Dueben: How did you work on the book?

Deacon: This is my first graphic novel so I’m literally making it up as a I go. The closest I’ve come to working on a graphic novel before was the book, Jim’s Lion. It’s a story by Russell Hoban, which was written as a picture book but we–the designer, the editor and myself–turned it into a young adult novel. Because it had been published once before in picture book format, we wanted to do something different with it. The approach we came up with was to alternate dream sequences that were comics illustrated by me with text chapters. The story is about a little boy with a serious illness who is awaiting an operation. He’s struggling with the bigness of these events and with his own very real terror and doubt. Our approach was to depict this struggle in silent dreams and keep to the waking world to the text.

For Geis, the method that I’ve come up with is to plan out a scenario in my head so I know what I’m aiming for and then I’ll break it down into sections and just improvise those sections in pencil, drawing them panel by panel. Then I go back and cut some bits out, change some parts until I have the whole thing and then I give it to people to read. I see how they respond to it and then improve the pacing and streamline elements. From there I can transpose it into something more legible–so you can read my handwriting–and make it look prettier.

Dueben: You have this bigger story, and epic fantasy tends to be very structured and very plot-heavy, but you take your time and spend time with different characters.

Deacon: I really value what you get from that creative process. You find that things you thought you would just skip through, when you actually draw the characters and see what’s around them and what they can see you think they would have something to say about it or they would want to walk over to take a look at the view. You have a sense of what their motivation or what their desires might be at a given moment. They don’t know that they’re in this big narrative–they have other concerns. They just want to get home and have dinner.

A couple of years ago I had to meet a friend in town and I was in my bathroom and I had no trousers on and there was a guy walking across the roof straight towards me. That’s not public property. He was definitely not meant to be there. The first thing that went through my brain was, this needs dealing with but I can’t because I have to go out and meet somebody. The individuals who can instantly throw out everything that’s in their head and engage with what’s happening to them right now are rare. I think most people have this kind of narrative chugging along in their brain and it takes a lot to turn that around. I get interested writing for those characters and just being in their headspace and trying to explore how they see the world. That takes a little bit of time to play out.

Dueben: We’ve both read a lot of fantasy stories where every characters knows what’s happened and why. Even though there’s no reason why every creature in this world would know all these things.

Deacon: And they so often know exactly what to do! I mean exposition is necessary of course but I do try to couch it with characters for whom it makes sense. Also I don’t mind characters being wrong or deliberately concealing things. I find it quite pleasing when you have characters who don’t tell you the full truth. I think that’s becoming a bit more of a thing. Maybe it’s George R.R. Martin’s fault?

I think people are very capable of working stuff out. You don’t have to spoon feed the audience. Even better than that, if you leave gaps and incomplete stuff, it’s not necessarily frustrating. I think people enjoy making up their own versions. In Star Wars when they have that off-hand mention of the Clone Wars, that was fun. One cartoon show and three trashy movies later, the Clone Wars mean something very different to me. It’s not what I imagined when I was eight. I think I like it less. So I prefer to leave gaps where people can insert their own interpretations.

Dueben: Talk a little about our heroine, Io. Was she always center of the story?

Deacon: No, actually. When I first started writing the story I literally did not know where I was going. I had a situation and I just began writing. I thought, who’s going to get back to the castle first? Well, she’s riding a log down a river, she’ll probably get back first. When I wrote that scene with her and Nemas, that’s when I saw where the story was going. The way that her and Nemas interacted changed what the story was and writing for her has shaped what the story has become. Just discovering her character has shaped the story. I began to get to know her better and I could appreciate what role she could play. She does have a backstory and you encounter it a little bit, but essentially she’s very much the opposite of the sorceress. She uses her strengths and her talents to help people. She’s prepared to give everything to stop this contest. That’s a very different attitude from just about everyone else in the story.

Dueben: Where are you on the second book?

Deacon: I’m about fifteen pages into the artwork, so I’ve got a lot of drawing ahead of me. The story’s all written, so it’ll be just months of continuous drawing. You do so much drawing in comics that it gets to be easier. [laughs] There are things I can do now that would have been extremely daunting a year or two ago because there’s just so much of it. There are some bits I’m really looking forward to drawing. It’s nice that some of the other characters will get a chance to get some air time as well. It’s a longer story, 120 pages instead of 80, there’s a bigger cast of characters. Hopefully it all ties together!

Dueben: There is this close relationship between picture books and comics and a lot of people move back and forth between the two forms. What are the big differences for you?

Deacon: One of the main differences is that individual images are less invested. Over my career in picture books I got really interested in narrative composition, the way that you compose things so they have a story significance. Using the space and the elements on the page is really important in picture books. In comics, it’s still important but you often find that you’re more dictated to by the fact that this character has to be in the same room, it has to be the same character, in the same costume. If I was writing a picture book I could put elements wherever I wanted to in the image to get across the meaning that I was after. Sometimes in a comic someone has to walk in a certain direction and they have to be the same room as seven other characters. There’s elements that I’m used to using in picture books to help get my meaning across which I don’t have access to in comics because of the need for continuity. That’s a big shift. Like the contextual elements–the lighting, the colors, what relationship the characters have spatially to each other–you can’t do that every panel. I’m beginning to think that some panels are more important than others. In a picture book, because the images have more weight, you’ll try something five-six-ten times over to get it just the way you want it. With comics you have a window in time. You have, say, an hour, to do this drawing. If you don’t get it right, you’re going to have to do twice as much tomorrow. It’s a different kind of pressure.

I also think it’s really important in comics that the images communicate well at a certain speed. It’s not healthy for a story if you get bogged down by the images. You’ve probably seen comic book work which is beautiful aesthetically, but very dense or ill defined. I think that rarely works well in a comic. You get stuck on those images. The narrative loses its flow. I don’t think it’s an accident that clear line became a big thing because it helps to bring image and word that little bit closer so that you don’t think you’re looking at artwork, you’re reading a narrative. I still have a ways to go on that journey. I think I could be better at it. It seems that the way you flow through the story is much more important in a comic. In a picture book you can often pause along the way and say, let’s spend five minutes seeing what animals we can see in this picture and then we’ll start the story up again. In a comic, not so much. In the second or third reading you can do that but the first time through, you’re going at quite a pace. I’m sure there are other differences as well but those are the ones I’ve noticed. I’m still in the learning curve for the whole business.

Dueben: So Geis: Book One is out now and Book Two is coming out next year?

Deacon: My hope is to bring them out one a year. Book three is one hundred and seventy pages so that’s more than double the length of book one, but I think we should be able to get it out for 2018. I should be able to start that before book two comes out. I’m aiming to get book two out for spring/summer next year and then get book three out in summer/autumn of 2018.