The opening titles of The Adventures of Tintin, while not technically part of the screenplay, offer a jaunty, tongue-in-cheek symposium on the action-adventure genre. Or, that is to say, on the films of Steven Spielberg. There’s a boy, he’s got a companion, in this case a dog, and there is danger and bad guys and all manner of vehicular transport, often in competition with each other, and a magical object, in this case a glowing ball, that everyone is after. This describes the plots of any number of Spielberg movies. If you wanted, you could expand the titles of Tintin into its own feature, and in fact just describing them would constitute a terrific pitch in most rooms in Hollywood. What is the glowing ball? The glowing ball is, of course, the maguffin, the thing around which the action revolves. For Spielberg, that might be the Ark of the Covenant, the Holy Grail, Devil’s Tower, Private Ryan or an enamelware factory. The point of the maguffin is that it doesn’t matter what it is, it only matters that it’s important to everyone in the story. It could literally be a glowing ball and it would still have the same effect, if exploited properly. At the end of the Tintin titles, it turns out that the glowing ball is the dot to the “i” in “Spielberg,” which adds the personal touch and brings home the fact that the sequence is, in large part, autobiographical — the chase for the maguffin, whatever it is, is the guiding principle of Spielberg’s life, the glow in his eye, or the light of his “I.” That the drama of the titles plays out on a typewriter instead of, say, a drawing board, or an editing table, brings that glowing “I” to the writer’s desk, that is, to the screenplay, where a movie always begins, where it must begin. It’s often been said that Spielberg makes movies about movies, here he acknowledges that openly.

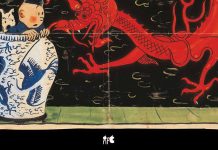

The Adventures of Tintin is also, of course, an adaptation of a series of beloved comic books, and Spielberg takes care to acknowledge that as well, before he gets on with the adventure. He has his Tintin pose for a caricaturist at a street fair, the caricaturist of course being Herge, Tintin’s creator. In this, Spielberg creates a kind of de facto hand off from Herge’s creation to his own, implying that he has (the late) cartoonist’s blessing on the project. Herge was dead for a decade before Spielberg even got the rights to make a Tintin movie, but the “handoff” moment still nods to the comics’ readers, says: it’s okay, we love this stuff too, trust us. (Part of Herge’s winning style was to take cartoonish-looking principals and put them in lush, well-researched, impeccably observed backgrounds, and Spielberg replicates that technique here in CGI — rubber-faced people in photo-realistic environments.)

What does Tintin want? Well, he’s a young man, living on his own, somewhere in Europe, some time in the 1930s, he wants adventure. Note that, in spite of living on his own and being old enough to drive, Tintin isn’t looking for love or sex, just the romance of adventure. I’m guessing Tintin shares that quality with Spielberg himself, who has always been skittish about love matters in his movies — Tintin, throughout his history, is permanently arrested in a pre-sexual adolescence –the perfect Spielberg protagonist. Maybe that’s why one of the first shots of Tintin is him passing by a row of mirrors — Tintin is Spielberg’s reflection of himself.

While a pickpocket deftly moves through the crowd in the market square and a pair of bumbling detectives pursue same, Tintin finds adventure, or the symbol of it anyway, in a ship’s model, The Unicorn, for sale by an antiques dealer. Tintin, like the young Spielberg, like young geeks everywhere throughout time, knows more about the ship than the dealer himself, the rigging, the guns, the year built, the king in power at the time. It is in the nature of the young man, not yet preoccupied with girls, to memorize all kinds of useless minutiae regarding vehicles, weapons and history — if he were born forty years later, Tintin would be playing Dungeons and Dragons.

Tintin buys the model ship and is immediately accosted by an older man who also wants it, all but announcing The Unicorn‘s status as a maguffin. Moments later, Tintin is approached a second time, by the bearded Sakharine, who is obviously sinister but who shares with Tintin a geek’s love of minutiae. There is a house, you see, a manor, and a sea captain, and a fortune lost — the stuff, in short, of adventure. Sakharine shows that the geek’s adoration of minutiae, when frozen too long, becomes obsession, as the enthusiast becomes the collector. Tintin is intrigued by Sakharine but unmoved: The Unicorn, and the adventure it symbolizes, is his.

Now, Tintin is a writer. Spielberg wants us to remember that — the first thing he shows us in Tintin’s apartment is his typewriter collection. That seems like a really odd choice; Spielberg doesn’t show Tintin’s collection of rare artifacts or model vehicles, Tintin’s main obsession is writing instruments. And we are reminded that Tintin is not just living adventures, he’s writing them as well. Hence the typewriter in the title sequence. One could say Tintin is writing his own life, and, in pursuit of adventure stories to write, writing his life into existence. Maybe that’s why Tintin exists in such a vague space of time and place — like a lot of young men, he exists in a world of his own mind, one without political realities or, for that matter, women and their complications.

Tintin comes in to his apartment with his new model ship, his new passport to adventure. He disregards the newspaper headlines trumpeting his past achievements, he doesn’t glance at the trophies and souveniers that litter his apartment. He heads straight for his office, where his current typewriter sits, and looks for his magnifying glass in a bookshelf filled with adventure books. Again, not just adventure is the key, but stories of adventure. Any journalist will tell you, any screenwriter as well, the story is the thing, you have nothing without it, and Tintin brims with stories.

A cat sneaks in, and Tintin’s dog Snowy gives chase, allowing Spielberg to indulge in one of his favorite and most fluent skills, physical comedy, a skill that movies like Saving Private Ryan and Lincoln don’t allow him to express very often. For that matter, the physical comedy of, say, Minority Report or The Terminal sometimes seems out of place in those narratives, but the world of Tintin allows him to let loose, let cats swing from chandeliers and dogs put their heads through photos of water buffalo.

Snowy’s pursuit of the cat breaks the ship model and a metal cylinder falls out of a mast and rolls under a bureau. Tintin, unaware, heads out looking for adventure at — where else? — the library.

The library Tintin goes to is stately and gloomy, a repository of arcane knowledge, a kind of temple, with pillars and stained glass windows a temple of stories, a temple of Story. Again, stories. Books, the end-product of the writer, the end-product of Tintin. Stories, told by people long dead, preserved in books to be lived again. It’s a kind of magic, one of the few forms of immortality actually available to people. The book Tintin reads about the Unicorn glows like one of Indiana Jones’s temple idols. Tintin recites the official story of the Unicorn as he reads, but Spielberg is smart enough to know that audiences never listen to exposition, not when it’s presented like this. He underlines what’s necessary — “What was the ship’s secret cargo, Snowy?” and lets the rest glide by, because the drama of the scene has nothing to do with what happened on the Unicorn all those years ago — pirates, a curse, a lone survivor — but what’s happening to Tintin. What’s happening to Tintin is that he is getting hooked, entering a mystery, entering an adventure. And, since Tintin’s life is nothing but adventure, adventure he writes himself, we could say that, in the library, he enters his life. Contrast Tintin with, say, James Bond. James Bond’s life isn’t saving the world, James Bond’s life is gambling and drinking and sexing up lovely ladies. ”Saving the world” is something that gets in the way of Bond’s goal of perpetual debauchery.

Or, contrast Tintin with someone closer to home, Indiana Jones. Indiana Jones must be taught, every single time, that the artifact isn’t important. He chases after his maguffin relentlessly, always to lose it, or give it up, in the end. For Indiana Jones, the journey to the maguffin is what counts, but he never wants to take that journey and never enjoys it while he’s on it. He’s single-minded and desperate in pursuit of his slippery goal while life passes him by. Another way to put it is, Indiana Jones pursues objects, while Tintin pursues stories.

He comes home from the library, the temple where stories go, like magic idols, to lie dormant until someone can open their secrets again, to find that someone has stolen his model ship. To you or me, that might be the end of it — “Well, it was probably that creepy Sakharine guy,” we’d say, “Jesus, it’s a good thing I wasn’t here, he must be pretty desperate.” But Tintin, as we’ve seen, lives for adventure, even if it’s a boy’s-adventure sort of adventure. That is to say, this kind of adventure, we all know, comes only from certain kinds of books, a literary genre, The Hardy Boys for instance. The character of Tintin is a callback to the past, not a real past but an imaginary past. There was never a time when there really were 15-year-old boys trotting the globe, solving mysteries and writing about their adventures. Sherlock Holmes was based on a real guy, James Bond sprung from a specific geo-political climate, Indiana Jones battles people in a more-or-less historical context, but Tintin is pure fantasy, has always been pure fantasy, and was created as part of a continuum of pure fantasy. Which is another way of saying that Tintin isn’t about a guy, there is no “there” there in Tintin, his vagueness lets the viewer fill him in, Tintin is about stories, and what they mean to us, certainly what they mean to Spielberg. Tintin seeks adventure stories to will his life into being, just as Spielberg did. Tintin has his Unicorn, Spielberg had his shark and his aliens and his Holy Grail.

But I digress. Tintin, his model ship stolen, heads to Marlinspike Hall, a creepy old manse out in the country.

He encounters some bother as he sneaks in: a locked gate, a slightly-troublesome Rottweiler and a butler with a kosh. Snowy helps with the Rottweiler; he is, in many ways, Tintin’s avatar, brave and innocent and eager, and those qualities generally serve to get him into and out of trouble. Tintin’s bete noir, Sakranine, his double and his opposite, lives in the crumbling Marlinspike Hall and owns, to Tintin’s surprise, a second model of the Unicorn. There is mention of the doomed Haddock clan and Sakharine generally acting threatening.

The mystery laid out in Tintin is clever but spare. There are no dead ends or wasted parts, no cul-de-sacs or red herrings. It’s meant for children to follow, and exists only to pulls Tintin through the story. As I say, the movie isn’t about Tintin, exactly, it’s about Sakharine, and, we will find, his relationship with Marlinspike Hall and this cursed Haddock clan. Tintin will draw them together and allow them to settle their hash, but has no real stake in the outcome. It is, perhaps, the curse of the boy’s-adventure hero to always be the facilitator of other people’s stories. They have adventures, but cannot change, while others’ lives are turned upside-down by their actions.

Tintin comes home to his find, for the second time in a night, his apartment burgled. Snowy, in some ways the better detective, points out what the thieves (this is either a different set of thieves from the people who stole the Unicorn, or else the same set of thieves coming back for something) came for: the metal cylinder hidden in the model ship’s mast. The cylinder contains a scrap of paper with opaque verse inscribed on it. A clue! This kind of device, of course, refers back to pirate romances, popularized by Robert Louis Stevenson but dating back to the 1700s. Pirate maps and buried treasure are a literary device unto themselves, there has never been such a thing in real life. Like Jim Hawkins in Treasure Island, Tintin gets swept up into his own kind of romance — not with Sakharine or the looming Haddock, but with the central mystery of the Unicorn. That’s why Tintin doesn’t need or seek a girlfriend, his narrative is about falling in love with a story.

The mystery deepens as the American who has been following Tintin shows up at his door, warns him for a second time, and is promptly shot. (Tintin, like any fifteen-year-old living on his own, has his own gun, of course. Teenagers in adventure fiction used to always have their own guns and cars. The Hardy Boys were handy with guns, and so was Nancy Drew, that is, up until the 1950s, when the stories were all re-written to appeal to postwar sensibilities.) The dying man, in the tradition of dying men in adventure stories, leaves a clue in his own blood.

Now that there’s been a murder, Tintin must bring in the police, here represented by the bumbling Thomson and Thompson. Thomson and Thompson are, of course, also types, the clueless authorities (one of them actually introduces them as being “completely clueless”). Again, they are throwbacks, not to an actual past but to a literary past, to Lestrad perhaps. The Tintin stories have always juggled types, slotting them in comfortably next to one another, allowing the reader to enjoy the style without worrying about motivations, which makes Tintin a kind of busman’s holiday for Spielberg, a chance to take well-worn characters and put them into an exercise of style.

Thomson and Thompson are vaguely curious about Dawes, the murdered American (he was an Interpol agent), but they’re preoccupied with the pickpocket we saw lifting wallets in the market square at the top of the movie. The pickpocket is soon upon them and yoinks Tintin’s wallet, which contains the precious scrap of paper from the Unicorn. Tintin gives chase, but loses the pickpocket. Upset that he has lost his new love (that is, his new story), he returns home, unaware that his love has come looking for him in the form of some roughnecks, who push him into a crate and make off with him. Love has found Tintin, but part of love is, lest we forget, to be stolen away.

He is brought to, not the Unicorn but another ship, a modern ship, the Karaboudjan. I was kind of hoping that “Karaboudjan” was an Armenian word for “unicorn” or some other mythological creature, but alas no, it is merely a darkly romantic nonsense word meant to evoke Mideastern intrigue. Since our protagonist has been shoved into a crate for his journey to the Karaboudjan, Spielberg temporarily shifts the narrative’s focus to Tintin’s avatar Snowy, who, in another physical-comedy-laden chase scene, follows the crate to the docks and thence on board the ship.

Tintin is placed in a cage in the ship’s hold and interrogated by Sakharine, who apparently has hired this vessel. Again, Sakharine and Tintin almost see eye to eye, the boy adventurer and the grown-up obsessive. Sakharine has one scroll (from his own Unicorn model), Tintin has lost his (to the pickpocket), Sakharine now needs Tintin (his younger self) to find a third scroll.

Sakharine is Hook to Tintin’s Peter, two sides to the same coin, or the same person on different sides of the hill. The boy who seeks adventure will eventually become a desperate, grasping pirate – unless he never grows up, which is, of course, the secret to Tintin’s enduring popularity: Tintin doesn’t age, doesn’t develop, doesn’t seek out romantic love or family or property. He is always a boy, without responsibility, not even to his dog. He’s without parents, without a childhood even, he seems to have simply emerged into his world as a fully-formed prepubescent asexual teenager, old enough to drive or pilot a plane or shoot a gun, but not old enough to yearn toward permanence. No wonder Spielberg was drawn to him, at his heart Spielberg has always been most comfortable in the role of the 15-year-old boy. He moved past his boyish obsessions and went on to create fully mature works like Schindler’s List and Munich, but you can sense his glee in being able to retreat back into the wholly imaginary world of Tintin: he’s Peter Pan without the tragedy.

Tintin escapes from his cage with some help from Snowy and meets the captain of the Karaboudjan, Haddock, of the aforementioned cursed Haddocks. Haddock has had his ship hijacked by Sakharine, he is the only holdout of the crew, the others have gladly gone to Sakharine’s side, modern-day pirates on a whole new Unicorn. Haddock has his own issues with maturity and responsibility: he’s a drunk, his cabin is strewn with empty bottles. He is, in his own way, another dark side of Tintin. If Sakharine is Tintin grown up, Haddock is Tintin grown up without ambition. Haddock went to sea, and to seed, no doubt looking for adventure, and no doubt looking to escape adulthood. Alcoholism as a disease has no place in the Tintin universe, it is a definite choice, the choice of a man abjuring responsibility even for his own ship. Sakharine refers to the Karaboudjan‘s first mate as “treacherous,” but who would choose to remain loyal to a captain with no goal further than his next bottle of whiskey? A captain must steer the ship, not founder his sensibilities.

Haddock, we learn, knows the secret of the Unicorn, or did, once, before he drank his memory away. Haddock has something Tintin does not: a heritage, and his alcoholism has betrayed it. I don’t think The Adventures of Tintin is supposed to be a serious examination of the effects of alcohol (although Haddock would make a good comparative to Denzel Washington’s drunk pilot in Flight), but it seems pointed that the first cast member of Tintin with a family has destroyed it with the bottle. The destruction of the family is, of course, Spielberg’s career-long central theme, his Rosebud as it were, so it’s not surprising that, as Act II of Tintin begins, the movie becomes Haddock’s. Spielberg may wish to retreat into the nostalgia Tintin evokes, but it’s Haddock that he gets to sink his narrative teeth into. We know that Tintin‘s narrative will not rest until Haddock has reinstated his heritage, reintegrated his family.

Tintin’s first adventure with Haddock is an enjoyable bit of hugger-mugger where Haddock must get a key from a sleeping sailor. He sends Tintin into a cabin filled with unsavory salts — a gambler who lost his eyelids in a poker game, a razor-wielding thug and a man openly described as a sheep-molestor. It’s understandable that Haddock doesn’t want to face these men himself, but his description of the men, in any kind of realistic sense, is horrifying, and the last place one would want to send a 15-year-old boy. Of course, the world of Tintin is essentially harmless, and the all-important keys turn out to open only the liquor cabinet. The beat cements Haddock’s relationship to both Tintin and to alcohol: he is a coward who would put a boy in the hands of murderers to satisfy his craving for escape.

While Haddock prepares to escape by lifeboat, Tintin goes to the ship’s radio room and does some detective work. He learns that the ship is headed to Morocco, where there is a sultan with the third model of the Unicorn. To entertain the viewer during Tintin’s recitation of exposition, Spielberg lets Snowy tussle with a rat over a sandwich.

Tintin, of course, doesn’t need to find the third model of the Unicorn, if his only goal were self-preservation he’d just go home (wherever “home” is). Tintin’s goal isn’t even to help Haddock save his heritage or to foil Sakharine in his quest for whatever-he’s-questing-for, his only goal is to get the story. The crew finds him, leading to a ship’s-deck fight that allows Tintin to fight, leap, shoot and scramble to safety. He reveals himself to be a hugely competent fighter, especially when contrasted with Haddock, a sea captain who’s incapable of even lowering a lifeboat. Tintin and Haddock are now thrown together at sea, two pieces of Sakharine’s puzzle, on their way to the next story point.

Tintin and Haddock have escaped the clutches of Sakharine and are adrift at sea. Tintin takes the moment to sit Haddock down and recite “what we know so far.” There are three models of the Unicorn, therefore three scrolls hidden within them. Sakharine has one, Tintin had one but doesn’t now, and Sakharine is on his way to get the third, from a sultan in Morocco. Sakharine needs Haddock because the legend says “only a True Haddock” can solve the secret of the Unicorn. Haddock, unfortunately, cannot remember anything, due to his alcoholism. (“Legends,” and their close kins “prophecies,” are great for adventure tales. They are always right and inarguable.)

This is a classic mid-movie pivot, not quite an act break, where the plot takes stock of itself and chaos begins to settle into manageable plot. Again, because the movie is meant to welcome youngsters, the mystery is clever but not difficult to solve or even keep track of. Clues are announced and always lead to correct deductions, and if they don’t (as in the case of “Karboudjan“, which was spelt out by the dying Dawes but led to no deductions at all) the plot steps forward to render deduction unnecessary. The pivot here is that the movie begins to become about Haddock. It’s not that it’s no longer about Tintin, because Tintin is still the journalist chasing the story, it’s that Tintin’s goal now becomes “to learn the story of Haddock.” He’s now chasing a story about a story, in the same way that Spielberg is making a movie about chasing a story about a boy chasing a story within a story.

I am not a Tintin expert, but my wife is, and I have found, while analyzing The Adventures of Tintin, Tintin’s innocence and timelessness striking. My wife informs me that Tintin, as a comic, was reflexive and self-aware from the beginning, that creator Herge was, like Spielberg, intentionally using and turning over various tropes and conventions in knowing references to established forms. Spielberg was part of what they called the “film school generation” of directors who made “movie-movies,” movies, the primary points of reference of which were not human experience but quotations from other movies; Herge could then be said to be creating “adventure-adventures,” comics, the primary points of reference being other adventure stories. As a child, one experiences Tintin as pure adventure, as an adult one reads it and grins at the warm tributes to this or that form of storytelling. That is to say, The Adventures of Tintin isn’t merely an exercise in nostalgia for Spielberg, it’s that that sense of nostalgia is a correct interpretation of the source material.

As Haddock clumsily points his now-tiny crew toward Morocco, Thomson and Thompson investigate Mr. Silk, the pickpocket. Of course, Thomson and Thompson, being classic idiots, do not believe Silk is the pickpocket but instead have come to return his wallet, which they got from him in their previous encounter. Their idiocy leads Silk to confess, but still they don’t suspect him of any crimes. Nevertheless, they find Tintin’s wallet in Silk’s apartment, among his vast collection of wallets — Silk, we find, does not steal wallets for the money but for their intrinsic beauty. He claims to be not a thief but a kleptomaniac; he’s close but not quite there — what he is is a collector. His mania, like Tintin’s, like Sakharine’s, like any arrested man-boy’s, is completion and classification. In the Spielbergian tradition, which demands that the cliche be stood on its head, the arrested man-boy is, ironically, not arrested by the police.

Meanwhile, at sea, Tintin has put himself in the hands of a drunken captain, a man so lost in whiskey that he forgets that one does not light a campfire in a lifeboat, which is a man lost indeed. Haddock blames his drinking on his distant relative Sir Francis, a man so great that he casts too deep a shadow on a mortal as ordinary as Haddock. Like Sakharine and Tintin and Mr. Silk, Haddock is arrested in a moment in time, unable to move forward and unable to accept responsibility for anything. His next step after realizing the error of sabotaging the lifeboat (Haddock, you could say, has been sabotaging his lifeboat all his life) is to announce a suicide attempt, in spite of the fifteen-year-old boy (and his dog) currently in his care.

Luckily, a new transport appears, in the form of a plane, sent by Sakharine to capture Haddock. Spielberg knows that adventure is about transport, both spiritual and physical; he claims that the Indiana Jones movies intentionally involve every form of transport known to their time (and some not, like, say, gigantic flying saucers and jungle-cutting machines). It is not enough, in an adventure story, that the plot keep moving, the protagonist must also keep moving. (The plane sent by Sakharine shoots at them, which seems to contradict Sakharine’s orders to take Haddock alive, but enough.)

Tintin, with one shot, brings down the plane, damaged but intact. Now he’s a teenage boy (with a dog) and a drunken sailor, pitted against two thugs with guns and a plane. This being Tintin, he turns the tables on them without a struggle and hijacks their plane. Spielberg indulges in a Jaws reference, briefly turning Tintin’s cowlick into a shark’s fin, a rare moment of actual self-quotation, and a wise one, since Jaws created such a demand for Jaws references in the world cinema market, Jaws references are now as much a part of world culture as Treasure Island or The Maltese Falconor The Hardy Boys or any other of the stories that Herge drew on when creating Tintin. Tintin is all about reflexivity, looking at stories through mirrors and lenses and frames, and while Spielberg directed Jaws, he no longer owns it — it has become a commonality. When he quoted Jaws in 1941 it was self-reference, but to quote Jaws in Tintincomments not on Jaws but on Jaws‘s place in the world marketplace of ideas.

Haddock politely requests that Tintin not steer the plane (which Tintin learns to fly after browsing the instruction manual) into a stormy “wall of death,” but Tintin ignores him. ”We can’t turn back,” he says, his face taking on the grim tone of obsession, “not now, not now.” And yet, why not? ”The Story” isn’t dependent on Tintin reaching Morocco before Sakharine, and, even if it were, he doesn’t have all the pieces, he only has Haddock. Tintin must become obsessive at this point in order to join Quint and Roy Neary and Keys and Capt Miller and Avner — Spielberg protagonists driven by an idea so consuming to them that they must pursue it regardless of the safety of others.

Tintin steers the plane carrying himself, his dog, Haddock and two bad guys into a storm Haddock calls “that wall of death,” leading to the first of Tintin‘s definitive set pieces, an action beat involving the plane, the storm, a boy pilot, a drunk, a bottle of medicinal alcohol, a sudden desert, a supercharged belch, a crash, an ill-timed parachute and a deadly propeller blade. Definitive because it would have been unstageable in any convincing way outside of 3D computer animation. The entirety of Tintin is gorgeous, but it’s sequences like this (and, to a lesser extent, the chase through the streets with Snowy after Tintin in the crate) where the movie comes into its own. Note as well that the “wall of death” sequence is rooted in character (“We can’t go back” and “I can’t stop drinking”) and, as in any true action sequence, it changes the direction of the story while it’s happening. Tintin and Haddock go into the storm as an obsessed boy and an unwilling coward, but the sequence ends with Tintin awakening Haddock’s courage and Haddock and Snowy rescuing Tintin from certain death — the first time anyone in the movie has shown a lick of responsibility toward anyone else. The principals go into the sequence as a boy, a man and a dog, but the emerge from it a family, that most sacred of institutions in the Spielberg ethos.

The team is now a family, but this newly-minted family is lost in the desert. The desert is dry, and so is Haddock — he’s sobering up. The dunes, for him, become waves. ”I must get back to the sea,” he says, meaning “I must escape responsibility again.” On the sea he can be perpetually drunk, on land the claws of responsibility can sink in. And yet, the sea is the natural home to a Haddock — Haddock’s flaw, we could say, is confusing alcohol with the ocean. In his miasma of shame, guilt and hallucination, Haddock experiences a change: he begins to remember the tale of the Unicorn. In another of the movie’s definitive touches, the landscape changes from dunes to waves before our eyes and the Unicorn sails again with Haddock’s forebear Sir Francis on its deck, facing the dread pirate Rackham.

The sea-battle flashback, like the wall-of-death sequence, could not be shot convincingly outside of 3D CG animation, and the juggling of dunes and waves, sunshine and storm, internal and external, show Spielberg at his imaginative best. Purely speaking, the sequence is exposition, the payoff of Tintin’s scene in the library — there it was words on paper, but in Haddock’s mind it is thrilling reality. That is, until the reality sets in: for Haddock, sobriety means responsibility. Responsibility to his family, his heritage, to Tintin, and to himself. That’s why, after the gang is rescued by some passing Legionnaires, Haddock takes the opportunity to become amnesiac. His desire to retreat, to remain arrested, is so great that he can now get drunk on water. As he lounges, memory-free, in the legionnaire’s infirmary, Snowy takes it upon himself to ply Haddock with rubbing alcohol, which puts Haddock back into his waking dream and delivers the rest of the exposition: Sir Francis was Haddock’s ancestor, the dread pirate Rackham was Sakharine’s (and the Unicorn‘s first mate was the ancestor of the butler at Marlinspike Hall).

In the flashback, Rackham takes over Sir Francis’s ship and demands to know the whereabouts of the “secret cargo,” a huge cache of riches. Sir Francis reveals the booty only when Rackham threatens to kill his men — this, of course, an inversion of the situation on the Karaboudjan, where Haddock’s men gladly turned on him. Sir Francis would lose his cargo because of his responsibility to his men, Haddock’s men would throw Haddock overboard to recover that same treasure.

It’s worth noting that Haddock’s regained memory of the sinking of the Unicorn echoes Quint’s recitation of the sinking of the Indianapolis in Jaws, a similarity Spielberg points to when he brings sharks in to devour Sir Francis’s men. Quint, like Haddock, is forever scarred by his memory of the his sunken ship. Quint was merely a mate and Haddock’s ancestor was the captain, but both men have let their sunken ship define their lives. It’s a little sad, I guess, that, in adapting Red Rackham‘s Treasure, Spielberg was unable to include the shark-sub that defines that comic.

Now, Rackham calls Sir Francis a lapdog of Charles II, which, although harsh, is fair — Sir Francis isn’t transporting the king’s riches for the sake of an orphanage somewhere, after all, he’s the guardian of the wealth of a monarchy, a soldier for the status quo. To Rackham, the king’s ownership of this property is theft, but in the Spielberg mindset, Sir Francis is merely a “good son” to Charles II, making it doubly ironic that Sir Francis’s descendant is the man without a family and it’s the descendant of Rackham who’s looking to regain his family’s heritage.

Tintin and Haddock journey by camel to Bagghar, getting there just ahead of Sakharine in the Karaboudjan. Where are we now, in the structure of The Adventures of Tintin? Good question. Timing-wise, the grand transition from Tintin and Haddock in the legionnaire’s camp to them arriving in Bagghar falls at 1:12:00, with 34 minutes left to go in the movie. Given an assumption of acts of equal length, that would make the move to Bagghar a natural move into Act III. But don’t forget, act breaks are not about location or transition, but about the journey of the protagonist. In Act I, Tintin became embroiled in a mystery that led him to be taken aboard the Karaboudjan, an irreversible direction, led to by a choice but not a choice in and of itself (although Tintin would have surely tried to sneak onto the Karaboudjan on his own, given the opportunity). Act II is then divided into three parts, typical of Spielberg: meeting Haddock, travelling with Haddock, and acting with Haddock. The entrance into Bagghar is only the beginning of that third chapter of Act II. And, as we’ll see, the traditional end-of-Act-II low point, where the protagonist has lost everything “but there was one thing he’d forgotten,” comes with a mere 14 minutes left in narrative. All of Tintin is brisk, but that’s super brisk for Spielberg. And yet, it’s not necessarily brisk for animation — many classics, for whatever reason, dating back to Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, follow what Jeffrey Katzenberg once explained to me as a “10-10-4″ structure: 10 beats in Act I, 10 beats to Act II, 4 beats to Act III, Act III being, as Katzenberg described it, “a race to the finish line.”

Tintin and Haddock move through the crowded, alien streets of Bagghar, haunted by the ghosts of the marketplace-chase of Raiders of the Lost Ark, then haunted by Thomson and Thompson, who have come, disguised as Arabs, to deliver Tintin’s wallet to him, giving him the scroll he needs to even the odds between him and Sakharine. Tintin, at this point, has surpassed his role as journalist, he’s gotten involved in the story he’s chasing. As I’ve noted before, Tintin is a journalist who routinely becomes his own story. Hunter Thompson would later define this technique as “Gonzo journalism,” but for Tintin the story is his whole identity, he has no life outside it.

Enter Bianca Castafiore, “The Milanese Nightingale,” here first seen upside-down through a portraitist’s lens, and reminding us again that Tintin is a text seen through a different kind of lens. All the principals of Tintin are introduced in distorted ways: Tintin is first seen through his Herge portrait, Thomson and Thompson through the framework of a newspaper, Haddock through an empty bottle, now Bianca Castafiore through a camera, all to remind us that Spielberg is seeing Herge through a lens as well, and that Herge was seeing boys-adventure stories through his own lens. (“What a dish!” cries Haddock when he sees a picture of Castafiore, the only mention in the narrative of a character responding sexually to, well, anything.) Sakharine has brought Castafiore to Bagghar (via a separate route than the Karaboudjan, apparently) to stage a concert for the sultan, where Castafiore will sing a note that will break the bullet-proof glass of the case holding the final model of the Unicorn. That this plan is absurdly complicated is beside the point.

Tintin gives his scroll to Haddock to protect, and Haddock responds as though Tintin has just asked him to marry him — terrified, then grateful. Terrified because it means responsibility, to both Tintin and his family; grateful because Tintin has placed faith in him, and connected him to his family. From the look on Haddock’s face, we can already tell that he’s going to screw this up.

Tintin goes to Castafiore’s recital and spies the Unicorn model nearby. Spielberg gives us two sets of lenses for this final puzzle piece: the bullet-proof glass and Tintin’s opera glasses. Haddock, although smitten with Castafiore, cannot abide the sound of her voice (neither can Snowy). Haddock abandons ship, so to speak, and goes to take a drink from a bottle he’s secreted in his pocket. Taking out the bottle sends the Unicorn scroll flying, and there’s a beat where Haddock holds the scroll in one hand, the bottle in the other, trying to decide which impulse to honor: to drink, and retreat, or to put the bottle down and face his responsibilities. The point is moot, because Sakharine’s thugs kosh him with the bottle and take the scroll. Meanwhile, at the recital, Castafiore hits her high notes, breaking all the glass in the sultan’s palace, in an orgy of lens-shattering. All hell breaks loose: Sakharine’s falcon (he’s got a falcon) snatches the last scroll from the Unicorn model, people scream and run, Haddock confesses to Tintin that he’s lost his scroll, and Tintin’s faith in Haddock, like all the glass in the sultan’s palace, is shattered.

This conflagration propels the great setpiece capping Act II, the chase down the mountainside to the docks. If this had been shot in live action it would be, hands down, the most astoundingly complicated sequence in history — stemming from story, rooted in character and geography and location, full of wit and dazzling physical comedy, dotted with dozens of trade-offs and constantly-changing stakes, irreversibly altering the narrative as it progresses to its end, and containing what is probably the most amazing single tracking shot in Spielberg’s career (which is saying a lot), and impossible to create without computer-generated 3D animation, it alone justifies the movie’s existence and should be studied by film students as an example of what an “action beat” should accomplish.

Tintin gets the scrolls in his hand, and now has his Haddock moment, where he must make a choice between his obsession (the secret of the Unicorn) and his responsibilities to those in his care (Haddock, and, almost parenthetically, Snowy). Tintin tries to split the difference, hanging onto the scrolls long enough to read the numbers that come through when the scrolls are held together against the sun, and Sakharine responds by throwing Haddock off the dock. This, then, is the end-of-Act-II low point: all the scrolls are gone, and Tintin is left with nothing but responsibilities — a boy-adventurer’s nightmare.

Tintin and Haddock are at an impasse. Tintin has lost the scrolls and his story, which means, to him, his identity — heis his story. Haddock has lost his ship — again — and thus his connection to his family. Tintin, despondent, is ready to give up, but Haddock bucks him up with what he intends to be a big inspirational speech on the nature of failure. Haddock succeeds, but not in the way he intended — instead, his truncated inspirational speech gives Tintin a practical idea, to track Sakharine by radio. Spielberg builds up a sentimental moment, then sweeps away the sentiment with a nuts-and-bolts answer — Tintin is not about introspection but action.

And so we plunge into the breathless Act III as the Karaboudjan comes to dock, right back where it set out, the city where Tintin lives. Sakharine, it seems, has pulled a Dorothy, gone searching the world over for his heart’s content only to learn it was in his own backyard. He gets into his car, to be taken back to Marlinspike Hall, only to find that his butler has betrayed him, a reversal of Haddock’s first mate’s betrayal aboard the Karaboudjian. That reversal leads to Tintin‘s final set-piece, a swordfight between Haddock and Sakharine, each fighting for the honor of his family, a reprise of the swordfight between Sir Francis and Red Rackham, this time with loading cranes. Why Sakharine would need to fight Haddock with something as absurdly complicated as a loading crane I have no idea, but the spectacle speaks for itself — it’s high comedy, it’s nothing we’ve ever seen before, and it’s thrillingly realized. (Sakharine being the descendant of Rackham is, incidentally, an invention of the screenplay: in the original comic he was an innocent model-boat enthusiast. Spielberg made him the kin of Rackham to bring him equal to Haddock, to make the struggle not just man-against-man but family-against-family.)

It may seem odd that The Adventures of Tintin devotes its entire third act to Haddock while Tintin frets on the sidelines, but the narrative has been headed this way from the beginning. The maguffin — the secret of the Unicorn — may have been Tintin’s story to find, but it was always Haddock’s cross to bear, and, as I’ve noted earlier, Tintin’s arc, whether he knows it or not, is to bring Haddock his heritage. Tintin, as a character, doesn’t bear the weight of family, he must remain above the fray of common human interest, but Haddock, even in his loopy, hapless state, does. A boy adventurer knows nothing of loss, but Haddock — the older Tintin, lost in his alcoholic cloud — does. In the end, Haddock beats Sakharine, not with the sword or the crane, but with alcohol — throwing bottles of it at him on the deck of the Karaboudjan until Sakharine falls overboard and is hauled out by Thomson and Thompson, who, for once, perform actual police work.

As the sun comes up on the docks, Spielberg cannot resist a “Spielberg shot” — characters gazing in wonder at something just off-camera. There is even a subtle joke involved: usually, the Spielberg Shot is a dolly in, but here Spielberg, always following the dictum to invert the cliche, here starts in close and dollies out. ”Do you see?” asks Tintin as the sun shines through the scrolls. Another self-quote, this time from Minority Report, a movie obsessed with vision, sight, and the accuracy of what one sees, applied here to pull together all the lenses and framing devices employed to make Tintin a meta-text.

The scrolls’ coordinates lead Haddock — where else — home. Specifically, his boyhood home. Spielberg has often spoken of the power of one’s boyhood home — it’s where dreams are built, after all — and by making Marlinspike Hall Haddock’s home, Spielberg takes ownership of the character. Tintin may be Spielberg’s retreat into his childhood, but Haddock is who he is now, a man looking back. At the end of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Indiana Jones says “Knowledge was their treasure,” but in Tintin the treasure is, literally, in the boyhood home, waiting in the secret room, the place where a boy plays his games, makes his plans, dreams his dreams, writes his adventures into his life and turns his life into his adventures, all in innocence, long before responsibilities arrive to carry him away to the world.

[Todd Alcott is a screenwriter living in Santa Monica with his wife and kids and cats and his dogs and his lizard. He has written many screenplays. Some have been made into feature films. You may have seen one.]

Clearly you have been writing this ever since the movie came out. An impressive article, but I can add a small detail:

“Now, Rackham calls Sir Francis a lapdog of Charles II, which, although harsh, is fair — Sir Francis isn’t transporting the king’s riches for the sake of an orphanage somewhere, after all, he’s the guardian of the wealth of a monarchy, a soldier for the status quo. To Rackham, the king’s ownership of this property is theft, but in the Spielberg mindset, Sir Francis is merely a “good son” to Charles II, making it doubly ironic that Sir Francis’s descendant is the man without a family and it’s the descendant of Rackham who’s looking to regain his family’s heritage.”

Oh, there is more to it. In the original book there are VERY subtle clues that Sir Francis (“François de Hadoque” in the original) could be the king’s own bastard son (in case, king Louis XIV, but Charles II was also well-known for his extramarital affairs), this being a veiled reference to Hergé’s doubts about his own family’s origins, his identical twin father and uncle (inspirations for the Thompsons) being themselves possible bastard sons of Belgium’s own king Leopold II (yet ANOTHER king known for his extramarital affairs!).

Details about Hergé’s possible royal heritage here, so that you won’t think I’m making stuff up:

http://socyberty.com/history/tintin-on-the-couch-to-tell-herg/

So, in more than one fashion, the treasure IS Haddock’s family treasure. And sure enough he wins it for himself in both the comic and the movie.

Yes, for a boy’s adventure comic, Tintin is incredibly layered. That’s why it is the most studied comic series in the world!

Comments are closed.