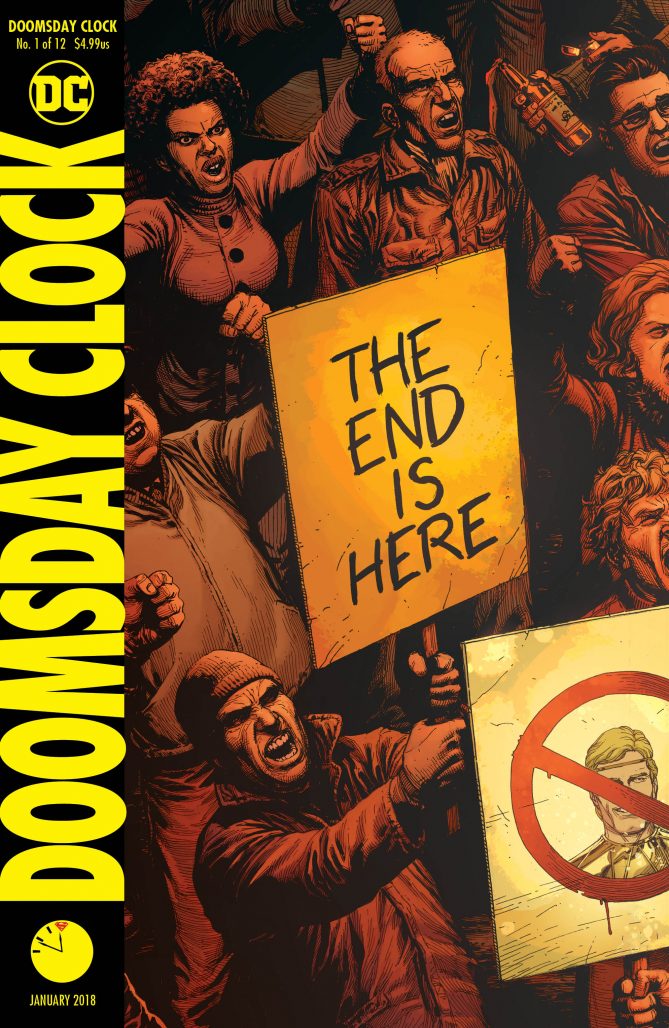

Doomsday Clock #1

Doomsday Clock #1

Writer: Geoff Johns

Artist: Gary Frank

Colorist: Brad Anderson

Letterer: Rob Leigh

[This title was provided to us by DC comics in advance of its release. The review that follows is spoiler-free.]

I never wanted a Watchmen sequel. When I first started reading comics I was– and really, still am– of the belief that stories are best when they have a beginning and an ending. Like a shooting star casting through one’s field of vision, it comes in, twinkles and sparks, and passes over the horizon. And among all the stars of those first comics I read, Alan Moore’s and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen burned the brightest.

While Watchmen wasn’t a perfect work—I don’t think such a thing exists—it was bold and coherent with its message. Moore and Gibbons knew exactly what they wanted to say and how they wanted to say it. The precision of the story and their understanding of its characters are undeniable. And for all its structural trappings, the best part of Watchmen was that it never overstayed its welcome.

But here we are, several decades later, on the eve of the release of Doomsday Clock #1, Geoff Johns’ and Gary Frank’s new installment in the Watchmen universe. Branded as a story where the characters from Watchmen meet the DC universe, it is perhaps equally apt to call it what Jim Lee did this past summer—a “sequel” to Moore’s and Gibbons’ seminal work.

And that’s troubling for me on several levels. From a simple narrative perspective, I feel like the arcs on most of the characters in the Watchmen universe are complete ones—yes, as Dr. Manhattan says, nothing really ever ends, but that doesn’t necessarily imply that continuing the story would be revelatory to the reader.

Then there’s the human issue. The legal rights issue. The one pundits and industry insiders have been litigating in public for decades now. The one where, as the story goes, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons were either screwed out of their rights to Watchmen by DC or were the unfortunate losers of a situation neither party realized would ever occur at the time of their contract’s signing—the way the story slants very much depends on where you fall on the issue. Either way, it’s a well-known fact that Moore didn’t, and doesn’t, want more stories told with Watchmen characters. But he’s not in a legal position of power to enforce the position.

And with those issues in mind, my position on Doomsday Clock should be relatively self-evident, but in truth, it isn’t. I’m conflicted. This is an issue that nags and pulls at me every time I think about anything involving Watchmen. I think it’s awful that DC’s relationship with Moore (and Gibbons to some extent) is so sour. And in an industry where more often than not, creators have historically been sidelined in favor of publishers’ bottom lines, in a fight like this one, my inclination is to side with Moore.

Moreover, in 2012, DC released Before Watchmen, a set of Watchmen prequels. Those books, in a final analysis, were half-cocked. If we’re being blunt, they felt closer to plays for fans’ wallets on the basis of nostalgia than they did to stories with their own messages. Thus, history is not on DC’s side for making a Watchmen universe story work.

That all said, I can’t help but think that Doomsday Clock #1 poses a captivating question: if the Watchmen universe is the embodiment of a cynical world, what happens when it butts up against the “hopeful” universe Johns has branded the current DC Universe as? Which worldview is ultimately stronger?

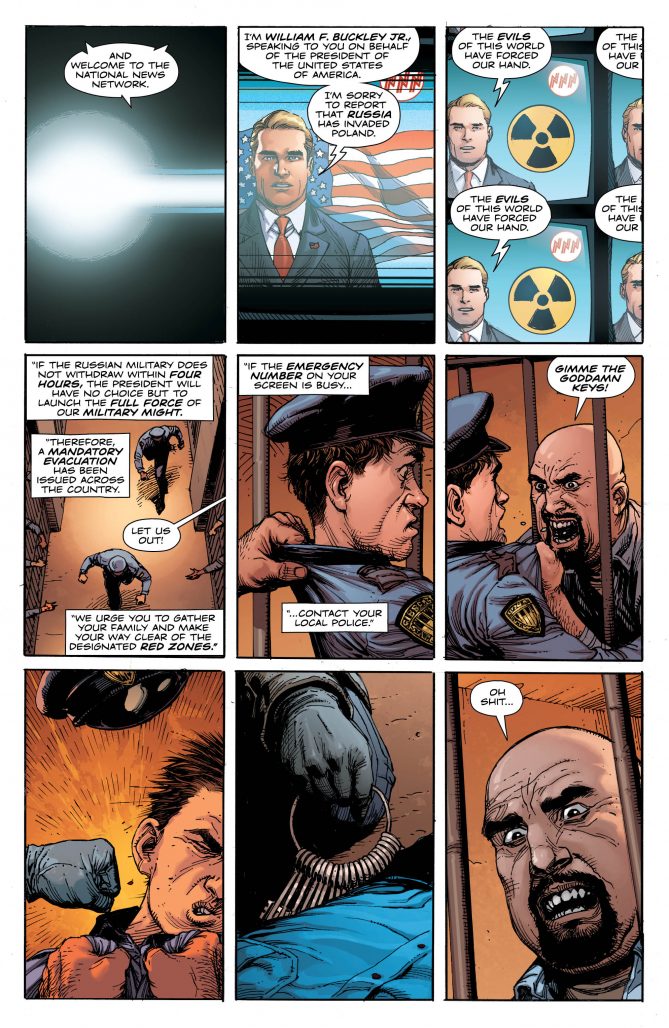

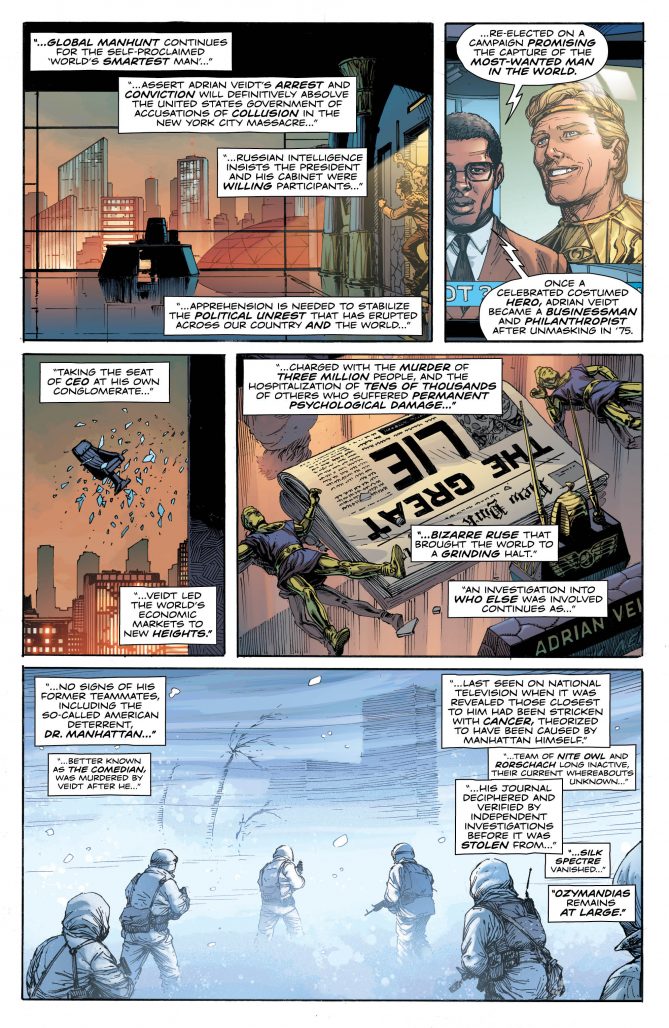

It’s a question of extremes that many of us find ourselves living out right now, as we look at competing, seemingly incompatible philosophies that pit protectionism against globalism. It’s one that the opening pages of Doomsday Clock examine in the first issue’s most overt homage to Watchmen, as we pan up from a doom-saying sign to a mob storming the offices of Adrian Veidt, Rorschach’s journal describing the context of the scene unfolding before us.

Strangely—or perhaps unsurprisingly—the elements of Doomsday Clock that most overtly homage Watchmen are the parts of this book that work the least for me. I don’t think the creative team nails the tone of Rorschach’s journal writing in the opening pages. And while you could explain some of that dissonance away via some other information presented to us in this comic, words like “undeplorables” feel too much like buzzwords than substantive critique.

Obviously the narration is meant to connect the events of this story to the events unfolding in modern America, but the excerpts here beat the nail over the head in a way that the original Rorschach’s journal entries didn’t. Those original screeds, while prescriptive about the way society worked, were simultaneously personal. Things like using the dog carcass in the alley as a metaphor for the reality of his city; like holding his father and President Truman up as paragons of “good men.” These entries taught us as much about Rorschach as they did about the world around him. They presented a specific perspective, whereas Doomsday Clock’s entry feels more like a gruff omni-present narrator bluntly laying out the situation facing the world. The personal elements—the most important parts—are lost, here.

The same is true of the text-based interstitials that appear in Doomsday Clock #1. Now granted, I found things like excerpts from Hollis Mason’s in universe biography, Under the Hood, to be somewhat grating to read in the original Watchmen. For whatever reason, it’s hard for my brain to switch to a predominantly textual way of consuming information when I’m in the middle of reading something mostly visual. But I do think those essay passages and interviews were important in the original Watchmen because they shaded interesting parts of the universe that we otherwise wouldn’t get to see. To be honest, I wouldn’t have blinked if the creative team had just dropped the interstitials completely in Doomsday Clock, but since they didn’t, I wish that they had presented us with newspaper clippings that did more than just reiterate Ozymandias’ failures to us. I wish they had told us something about some of the new characters introduced in Doomsday Clock #1, for example.

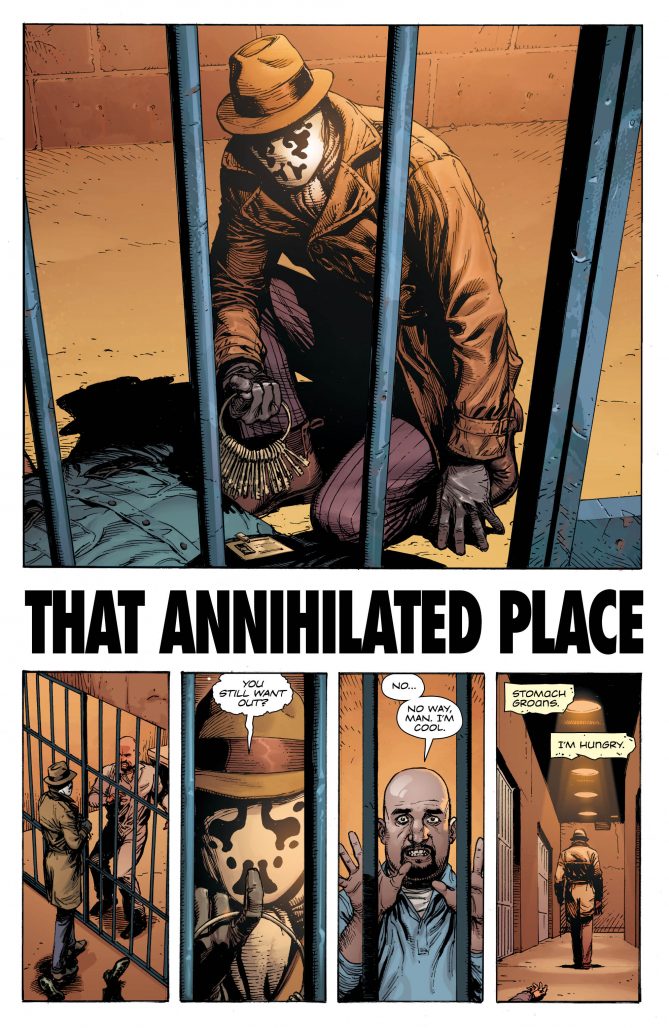

But not all of Doomsday Clock’s attempts to channel Watchmen fall flat. Artist Gary Frank, in conjunction with colorist Brad Anderson, do a singular job of channeling the artistic style that made Gibbons’ work in Watchmen so memorable. Everything you loved (or maybe just what I loved) about Gibbons’ wonderful nine panel grid layouts are all here—the tight focus in action sequences, intensely detailed facial expressions, and moment-to-moment transitions galore. While many have channeled the legacy of Watchmen through their use of the nine panel grid in storytelling—Tom King and his collaborators are perhaps the most obvious examples at the moment—there’s something special about seeing this style and approach applied once more to the content that made it famous, but with a twist.

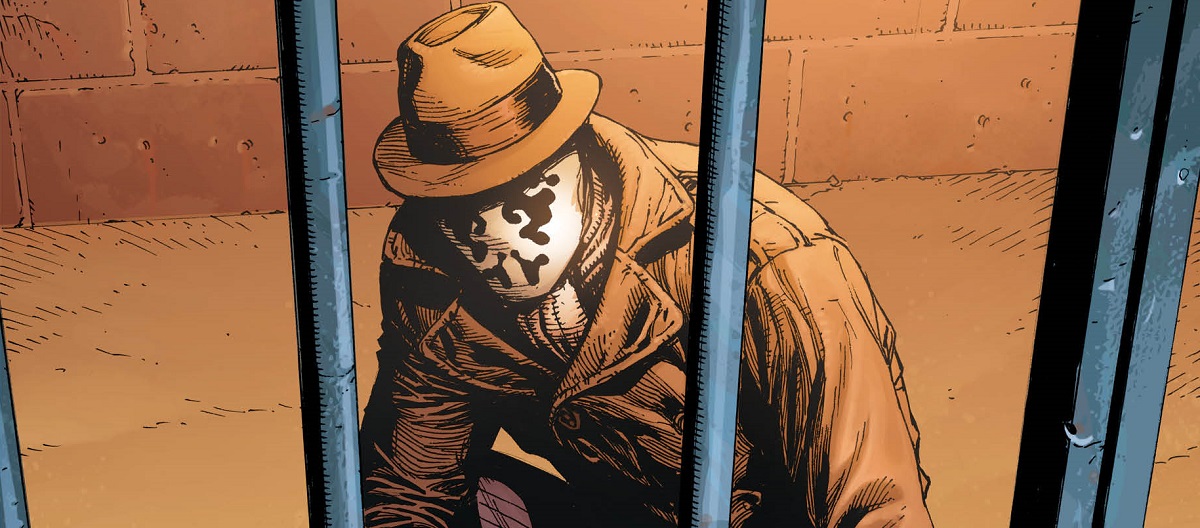

And in this twist of characterization, the reason why Johns would find tackling Moore’s legacy in spite of the hairy issues it raises becomes clearer. Over the years, Johns has become known as something of a doctor for DC properties he considers under-served– Hal Jordan, Barry Allen, Aquaman, are just some of the more successful characters that he is considered to have helped repair the reputations of over the years. Reinvented them, so to speak, much in the same way that Moore and Gibbons reinvented Charlton Comics characters for the original Watchmen series. And while Rorschach’s character may not have needed a reinvention in a vacuum, there’s evidence to indicate that the way the public interprets Rorschach has become skewed in a way that may necessitate a response. So if Johns thinks he has the answer to this problem, I’m willing to hear him out.

So in the end, our discussion of Doomsday Clock comes back to the beginning. It comes back to premise. And again, when it comes to premise, I remain hesitant about this series. Several of the more overt homages to Watchmen in Doomsday Clock #1 fall flat. They do the book something of a disservice, really, because Doomsday Clock is much more impressive when it uses Watchmen as an inspiration than as a guidebook. The deconstructive, meta-fictional question the creative team poses through Doomsday Clock is its most subtextual, yet easily its best usage of the Watchmen brand. The original characters introduced here and their morbid senses of humor feel much more natural and refreshing than another lecture about how there are bad people on “both sides.” And finally, the small peek that we do get to see of the DC Universe is easily Johns writing at his best, giving us a cliffhanger as chilling as touching steel on a winter’s day.

Whether Doomsday Clock ends up being worth it in the end will depend on whether or not it was worth it to overtly bring the Watchmen into the DC universe instead of indirectly channeling the tone, style, and characterizations of Moore’s and Gibbons’ work into a story that only takes place in the DC Universe. And that’s not an assessment I’m prepared to make at this time. If you’re inclined to dismiss Doomsday Clock out of premise, I don’t think that anything here will change your mind. But Johns, Frank, Anderson, and Leigh do make a valiant first attempt to climb the critical mountain they’ve built for themselves here, and in my eyes, they get further than I initially expected that they might.

Johns has been living off of Moore’s work for over a decade now. He’s a skilled imitator but there’s nothing more to his writing than that. His is a hollow, creatively bankrupt endeavour whose commercial success glosses over the fact that he’s never created a new character or idea or even a story that doesn’t in some way relate back to Moore. He’s the definition of a hack, personally profiting off of the misfortune of creators before him who created truly groundbreaking, thought provoking work.

Love him or hate him, Moore has always stood for something. Creators right (not just his own) mattered to him, amongst many other things. Watchmen cannot be recreated by an empty vessel like Johns.

Everyone involved in this project should just be embarrassed. It’s a weak and desperate move from a creatively spent editorial team. Let’s move on.

PreacherCain… that’s harsh. Johns is an excellent writer. Complaining he’s not as good as Moore was at his peak is unreasonable.

What would Johns do without Alan Moore’s work to always rip off and repurpose? Has he ever had one original idea or contribution to comics?

And before anyone says “JSA,” I read that entire run. There was not one good moment or worthwhile idea in the entire comic. It was all “remember this old character?” and “shocking” scenes of violence.

Anyone who reads this comic must really hate creator rights and originality.

The idea thay Johns, authors of countless pornographically violebt comics starring children’s characters, somehow represents “optimism” is absolutely ludicrous.

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons got screwed. Plain and simple. I got the Watchmen in it’s original 12 issue form. (Yes, I am old.) That works for me and Moore seems like a stand up guy so I see no reason to contribute to more of this nonsense. I will not be buying this book. Rorschach seems pretty lively for a dead guy.

I first read Watchmen years after it was released. And perhaps because other books had deconstructed superheroes since it was published, it, honestly, did not impress me all that much. It was an entertaining read, but I came to it too late, I think, to be wowed and to fully appreciate it.

So while kind of intrigued by the idea that somehow Doc Manhattan is to blame for DC’s horrible New52 reboot, I’m not really all that excited about a return to the Watchmen universe.

And, though I’ve enjoyed some of Johns’ work in the past — JSA — I also am not confident he has the writing chops to pull this off. I’d be more confident if, say, Grant Morrison or Mark Waid or Kurt Busiek were attempting this. Johns is just not a subtle writer.

Lastly, we’ve kinda been here before with Geoff Johns. Wasn’t Infinite Crisis – his sequel. to the original Crisis – all about how the pre-Crisis Superman and Superboy were disgusted with the Modern Day DCU and the grim and gritty-ness of modern comics?

And while Johns at heart may truly be an optimistic guy who believes in heroes doing good and triumphing over evil, he has done his fair share to make DC darker. It was Johns, wasn’t it, who introduced the murder of Barry Allen’s mom into his origin, wasn’t it? Barry Allen – the shining, optimistic beacon of DC’s Silver Age…

And let’s not forget the violent, petulant Superboy Prime character…

Oh, and Blackest Night, where “coooooool” evil zombie versions of dead DC heroes rise to terrorize the living…

So when Johns starts talking about wanting to tell a story about optimism and heroism versus grim-n-grittiness, I have a hard time figuring out which side he’s on…

“David Taylor on 11/20/2017 5:48 am at 5:48 am

PreacherCain… that’s harsh. Johns is an excellent writer. Complaining he’s not as good as Moore was at his peak is unreasonable”

Apologies if I wasn’t clear. My complaint isn’t so much that he’s not as good a writer as Moore (there’s few who could claim that), but that ALL of his most successful stories and ideas seem tied directly to what Moore has done in the past. He’s spent most of his career playing around with Moore’s ideas and plots in some way and has personally benefitted not just from Moore’s ideas but his (and many others’) battles for creator rights.

How is Geoff Johns then, not a hack? He fits the bill perfectly, far as I’m concerned.

DC and Johns should be taken to task over it far more often but these days (aside from The Beat and BC to an extent), comics journalism appears to be regurgitating press releases that tow the party line.

Before Watchmen and Doomsday Clock are an attack on creators rights. It’s an attack on comics. It’s an attack on us and the medium we love.

Rorschach rant over :) Far as I’m concerned, everyone who wants to read this comic should pirate it. It’s been stolen already.

“Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons got screwed. Plain and simple.”

How did they get screwed? They signed a better then average contract with vocal agreement based on past sales that they would get control back in 3 to 5 years because up to that time no graphic novel had ever sold like that.

If anyone van pull off artwork compareable to Dave’s work on Watchmen, it is Gary Frank. The art I’ve seen so far looks very good. But when I see Rorschach walking about, I just think: ‘But he is dead, I saw him die!’

I don’t know how this is possible, and I don’t want to know. Sorry.

PreacherCain: “Everyone involved in this project should just be embarrassed. It’s a weak and desperate move from a creatively spent editorial team. Let’s move on.”

“Before Watchmen and Doomsday Clock are an attack on creators rights. It’s an attack on comics. It’s an attack on us and the medium we love.”

Wow. You really like the over-the-top melodrama, huh?

“Watchmen” has cast far too big a shadow across comics for far too long. It’s way past time someone struck back against “grim and gritty.” Can’t. Wait.

“Wow. You really like the over-the-top melodrama, huh?”

Well, it’s an article about colourful men fighting crime in tights… so… yeah (⊙_⊙)

@Charles E Brown DC keeps publishing it in perpetuity so they don’t have to honor their agreement. That might actually be the definition of screwed

@Brian You’re right that Johns already played with these themes in Infinite Crisis, and for all the “new direction” talk being thrown around alongside the criticism of darkness in comics, what DC went back to is Prometheus murdering kids and Wonder Twins being eaten by a dog. It’s a situation similar to Batman where he’s thrown into an epic story that ends in him “loosening up,” then next month he goes right back to abusing his sidekicks. All this criticism of darkness in comics rings hollow when these writers can’t show us what the other side is supposed to look like. (I do enjoy Morrison’s tackling of the subject with Seven Soldiers, Multiversity and his Batman run, but the endings to those stories are entirely open-ended.)

genius 1st issue Johns has out “Alan Moore’d” Alan Moore …revitalizing classic concepts and taking them to the next level ….

This isn’t my cup of tea but comics has been repurposing ideas and characters for 80 years. I’m not going to start getting upset about it now.

Comments are closed.