Aliens Vs Avengers TP

Aliens Vs Avengers TP

Writer: Jonathan Hickman

Artist: Esad Ribić

Colorist: Ive Svorcina

Letterer: Cory Petit

Publisher: Marvel Comics

Publication Date: August 2025

“There’s a horror movie called Alien? That’s really offensive. No wonder everyone keeps invading you.”

-Steven Moffat, Last Christmas

To understand the nature of Aliens vs. Avengers, we must first engage with the nature of Alien. Not simply with regards to the franchise that spawned these pure monstrosities — be it the production history or the Lore — but rather the full extent upon which these stories function as narratives. To wit, there are three molds upon which Alien stories function. Each one perfectly encapsulated by a different film within the series: Alien, Aliens, and Alien: Covenant. (There’s also Species, but that would complicate this article in a way that would be too tangential.)

It is easy to forget what Alien was with what came after. When watching the film, there’s an air of the unknown. Not simply with regards to the experiences of the characters, but rather with the way in which Ridley Scott explores the world. For the film’s first five minutes, we wander the empty liminal spaces of the spaceship Nostromo. There is someone here, we can hear it moving around the ship. But we cannot see it. We are left with the discomfort of not knowing, even as we learn more.

These are, of course, the hallmarks of your traditional Haunted House story, of which Ambiguity is a vital aspect. Perhaps the most famous haunted house story is Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House. There, a group of paranormal researchers and volunteers enter a haunted house to see what’s going on. However, we experience the story through the perspective of just one of them, Eleanor Vance. As such, we have to consider the subjectivity of Eleanor’s perspective. Is there a real ghost in the house or is she simply having a nervous breakdown due to her repressed sexuality?

Equally, there’s It! The Terror From Beyond Space, which is often cited as a major influence on Alien. In that film, the crew of the second mission to Mars find themselves under siege by an alien lifeform. At least, that’s what the survivor of the first mission, Col. Edward Carruthers claims. Before the alien makes its presence known, the second team assume Carruthers is a murderer who made a “tough call.” It is only when the alien presence makes itself known that they read the astronaut differently.

But what makes Alien different is the lack of professionals within the core cast. As can be surmised, its precursor It! The Terror From Beyond Space is comprised predominately with square jaw space men ready to colonize the stars. And while The Haunting of Hill House has volunteers as its core cast, they are both lead by a professional paranormal investigator as well as each having their own experiences with the supernatural.Alien, meanwhile, is comprised of a cast of characters who are out of their depths before the titular alien even shows up. They aren’t explorers visiting strange new worlds; seeking out new life and new civilizations; boldly going where no man has gone before! They’re space truckers whose parent company is willing to kill them all to make some money on a, frankly, insane plan involving a killer alien. They’re not even supposed to be here today!

The concept of money and being paid is a key concern throughout the film. As space truckers, our heroes are working paycheck to paycheck in dangerous situations. Indeed, the mundanity of Alien is what sets it apart from what comes after more than any of the follow ups. Removing them from the context of a science fiction horror film, these characters could be seen in any movie from the late 70s. Indeed, Harry Dean Stanton essentially made a career out of playing working class joes like Brett trying to make ends meet.

In turn, however, this mundanity gives rise to the central horror of the movie: rape. It is no small bout of imagination to surmise that the titular alien has a degree of phallicism to its design (as to be expected from the work of H. R. Giger). But beyond that, there’s the initial tension of Alien’s second act: the rape and pregnancy of John Hurt’s Kane. He is forcibly impregnated with an alien embryo from which the movie’s monster is born. Characters even refer to the creature as “Kane’s son.” And the act of penetration is depicted by Scott as akin to a rape scene with each moment of the copulation depicted in a frenzy of quick cuts that disrupt the visual language of longer takes. As co-writer Dan O’Bannon put it in behind the scenes material, “This is a movie about alien interspecies rape.”

And when the alien is fully formed, its first victim is Brett. The creature hides in plain sight as Brett is all alone, living his life as normal. He’s just trying to find the ship’s cat. The scene is shot to look like an alleyway that pop culture has viewed many a rape to appear in. And, as with many scenes like it, a tall, dark stranger comes swooping in for a deadly kiss. The cultural image of sexual predation brought to life and forced upon men. This is further compounded upon in the (admittedly lesser) director’s cut, wherein the alien’s attack has an air of sensuality to it. The scorpion like tail going between Brett’s legs, its hands caressing his face like a lover’s touch, forcing our working class hero in for that kiss.

But arguably the most striking implication of sexual violence comes with the attempted murder of Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley at the hands of Ian Holm’s Ash. In science fiction, it is often the case to see a robot attempt to murder one of the human characters. (It’s notable, then, that Alien does not reveal robots are a part of the setting until Ash’s attempted murder fails.) However, where most movies would have the android kill the humans with superhuman strength or some weapon inside their body, Ash opts to try to kill Ripley with a rolled up porn magazine found not too far away. The scene is made even more unsettling as Ash rolls the magazine up into a phallic shape and shoves it atop Ripley’s mouth.

And yet, the intent on O’Bannon’s part was not to “go after the women in the audience. I’m gonna go after the men. I am going to put in every image I can think of to make the men in the audience cross their legs. Homosexual oral rape, birth. The thing lays its eggs down your throat, the whole number.” For all that Ash’s attempted murder an extremely striking scene, the more striking aspects of this implication come in the form of what happens to Kane and Brett. There’s a disorientation to the scene. The camera pans around Ash as he contemplates how best to go about his actions (including once again having an unknown force cause diegetic noise in the background that should be impossible) in a way that goes against the visual language of the film. But it doesn’t have the raw existential dread of the unknown that the alien brings to each of its scenes.

Alien stories, then, are defined not simply by having the lone alien creature stalk a haunted spaceship. Rather, they are defined by the tension brought about by the mundane concerns of capital and sexual assault brought to startling degree within the contexts of a cosmological evil. It is a universe full of unknowns and mysteries. And one of them will not stop, no matter how hard you try to kill it.

By contrast, Aliens immediately tosses wave after wave of disposable aliens at a platoon of Colonial Marines. There’s a degree of familiarity to this new interpretation of the alien, now called a Xenomorph to expunge it from any and all traces of unknowability. Even from its opening shot of space, there’s a warmth with a blue that makes the view feel less alienated by the cosmos in contrast to the stark blackness of Scott’s original picture. (Borne, no doubt, from the romantic view of nature held by James Cameron.) Though our story finds heroine Ellen Ripley in a far off future, it doesn’t feel all that meaningfully distant from the world she left behind in the earlier film. It feels like the same capitalistic hellscape that would deem its lowest wage slaves disposable.

Another notable detail is how long it takes for the Xenomorph to makes its appearance in the film. While the original luxuriated in the unknown of its setting for roughly thirty minutes before showing us the titular creature, in Aliens, we see the Xenomorph in eight minutes (albeit under Ripley’s flesh in a dream sequence). While it could be forgiven as a sequel lacking the inherent mystery of its previous film, it still remains a rather banal choice for a cheap scare instead of building up an atmosphere of dread.

Tellingly, it’s Ripley who’s the victim of the chestburster instead of a man like Kane. In fact, she and Carrie Henn’s Newt are the only ones in the entire film to be menaced by the facehugger (first in a scene where they’re locked in a room with two facehuggers, then again when Newt is playing the role of peril monkey with the Xenomorph queen) with the only actual chestbuster victim we see a Xenomorph come out of likewise being female. Indeed, the first colonial marine to be attacked by a Xenomorph in its fully grown incarnation is likewise female. And the first kill in the film done with the iconic second mouth is done to the female fighter pilot. Sure, there are male victims. But by highlighting the female victims to this degree, it lessens the implications O’Bannon came in with.

This, in turn, removes the subtextual theme of male rape from the film and instead makes the overall message one of heteronormative girl power that was in vogue in the late 80’s. It is worth contrasting the characters of Ripley and Jenette Goldstein’s Vasquez within the context of the film. Vasquez is a tough as nails soldier who embraces masculinity. The film highlights this aspect of her character via having Bill Paxton’s character, Hudson, snark “Has anyone ever mistaken you for a man?” with Vasquez coldly replying “No. Have you?” Aesthetically speaking, she evokes the Butch Woman that Cameron would further codify in Terminator 2: Judgment Day with Sarah Conner. But in contrast to that iconic female heroine, Vasquez dies, and in such a way as to highlight her lack of agency in comparison to her male counterparts. Ripley, meanwhile, takes on a more nurturing role, embracing her femineity via adopting an orphaned girl, beginning a relationship with a rare Michael Biehn character who doesn’t die at the end of the film, and defeating an evil mother. Indeed, her interactions with Newt soften her from her harden exterior as seen in the original Alien, wherein she coldly refuses to let the impregnated Kane into the ship due to being a biohazard. While these elements in and of themselves are not bad, contextualized with the original Alien makes this feel like a forced normalization of the material away from the thornier aspects of the original.

Consider how they portray the company. In Alien, the corporation is an unnamed force that has schemes of its own outside of the mentality of the working class joes trying to earn a living. It is, much like the alien, a thing of cosmic horror that infringes upon the lives of those who must survive within its gullet, knowing full well that they are as disposable as the next schmuck. Even its representative, Ash, isn’t human. He’s just another tool at the corporation’s disposal to get what it wants.

In Aliens, meanwhile, the corporation is called Weyland-Yutani. It has human representatives (including a chairman of the board doing a rather mid Richard Nixon impression), a human representative on the ground, Paul Reiser’s Carter J Burke oozing his way on set as a corporate climber, and meets a rather human end with Burke being hoisted by his own petard. These feel like normal things to happen in a movie where the secondary baddie is corporatism.

But then, this should be expected considering the genre of the film. Where Alien is a horror movie, Aliens is an action movie. Of specific note, it is a war movie, such that it’s tagline is literally “This Time It’s War.” The most obvious influence in this regard, given the various signifiers, is the Vietnam War. You have shell shocked troops going into unknown territory, only to find an inhospitable and unstoppable force of enemy utilizing the terrain such that they could be hiding anywhere.

Cinematically, this kind of warfare was depicted in films such as Platoon or The Deer Hunter. In these films, we get inside the heads of the soldiers as they march forth into the heart of darkness. We see the psychological turmoil that faces our ragtag bunch as they approach certain death and come away, at best, mentally scarred. Equally, you can see the influence of the old school science fiction films. Many of them featured soldiers uncovering unknown horrors and being initially overwhelmed by their cosmic significance before using their all American know-how to fight them off. Aliens differs in that the soldiers all end up dead in ignoble ways.

But what’s vital about all of this is the dehumanization of the enemy. For all that the American War Film about Vietnam humanizes the soldiers, it is the American soldiers who find themselves with all the humanity. Even more recent and subversive fare like Da 5 Bloods finds itself using the nation of Vietnam as a learning center for its American protagonists, barely caring about the lives of the Vietnamese in contrast to Delroy Lindo’s harrowing performance as a self-hating Trump supporter.

Aliens, quite crassly, frames its Xenomorphs as a literal horde of subhuman monsters led by a vicious queen with the sole intention of out populating the human race, using human bodies as a form of reproduction. The only person speaking against, in the film’s own words, “exterminating” the Xenomorphs is the cutthroat corporate raider who sees a profit in keeping them alive. With the thematic implications of the Vietnam War looming within the film’s subtext, this framing of the alien lifeforms as an unending horde of barbarians waiting to overcome the walls of our empire is kinda fucked.

At the same time, Aliens was the version of the story that was ultimately embraced by the wider culture. Spin off after spin off told stories not of working class heroes trying to survive in a world where they lack agency, but of Colonial Marines exterminating all the brutes. Mowing down the Xenomorph as if it’s just one in a long line of mindless alien baddie, like Heinlein’s Skinnies or Tolkien’s Orcs. And the people loved it.

In many regards Ridley Scott’s return to the franchise with Prometheus and, more importantly, Alien: Covenantwas a reaction to this. While Prometheus approached the material in an almost cracked mirror version of Star Trek — complete with away teams, science officers, and other templates of that New Wave science fiction show — it’s Alien: Covenant where things get especially spicy.

For starters, space in Alien: Covenant is vast. Where the previous two films discussed portrayed space as either inhospitable and dark or cool and soothing, they both had their respective spaceships be depicted as large objects be it Ron Cobb’s gothic castle or Syd Mead’s giant gun. But the USCSS Covenant is initially depicted on screen as nothing more than a tiny dot, barely visible in the dark ocean of stars.

It is this smallness in the cosmic scheme of things that is vital in understanding what Alien: Covenant truly is. On this front, it is worth considering the character of Billy Crudup’s Oram. After an accident involving a solar wind that results in mass casualties, second in command Oram is made captain of the Covenant crew. However, upon first appearance, it is abundantly clear that he is not ready for prime time. When addressing the crew about the mass casualty event, Crudup plays the role uncertain, full of misspoken words, awkward pauses, and a number of filler words. He quickly blames his own inadequacies on his religion, constantly starts arguments with second in command Daniels (played by Katherine Waterston), and makes several impulsive decisions that lead to people dying horribly.

Among them being his wife, Carmen Ejogo’s Karine. In one of the many sequences (consciously or not) rebuking the logic of Aliens, an imperfect hybrid creature gets on board a transport vessel and immediately begins to kill people. Amy Seimetz’s Faris, upon seeing this creature of impossible origin begin to birth itself from the spine of Benjamin Rigby’s Ledward, immediately bolts, leaving Kariene to die. (Indeed, Faris freezes upon seeing the puking Ledward.) Maggie grabs a gun to kill the creature dead, only for her attempt not only to fail to kill it, but also lead to her own gruesome demise.

We see this pattern of the failures of humanity in our supposed best and brightest recur throughout this duology. (One infamous scene in Prometheus involving a scientist getting a little bit too close to an alien cobra just to show off to a soldier type.) And it is all with a single clear intent: to highlight just how much contempt the universe has for humanity. The cosmos as imagined in these two films is one where upon finding the Creator who descended onto Earth via the Chariot of the Gods, God looked at his creation and immediately started killing it like flies. The universe of these films is hostile, full of horrors and cruelties. None more so than Michael Fassbender’s David.

There are two important things to note about David. Firstly, he is an artist. He is shown throughout Alien: Covenant creating his own clothing, drawing, and performing music. In one particularly homoerotic scene, David works with his fellow robot, Walter (also played by Fassbender, doing a gruff American accent), to play the flute. At one point, David even notes “I’ll do the fingering.” In many regards, his core need is a desire to be seen and understood. In his first scene in the film, he confronts his father, Guy Pierce’s Peter Weyland, with his mortality, to which Weyland responds with a petulant act of control. When he meets God, David is once again disappointed in this creator, finding no equal. And so, he does the only sensible thing when confronted with a lacking God: He exterminates the entire species and decides to become a God via creating life.

This brings us to the second thing to note about David: he is completely and utterly bugnut insane and the inevitable endpoint of the colonialist thought that made man think it could colonize the darkest corners of the skies the way it colonized the darkest corners of Africa. Indeed, this theme can be seen within the subconscious of the franchise to this endpoint. In Alien, the demands of a corporation are to investigate an unknown planet for fun and profit, mining the planet of its resources. In Aliens, the foot soldiers who call themselves Colonial Marines investigate one of Weyland-Yutani’s colonies. Alien3, though not a focus of this article, has the dregs of society abandoned on a prison planet as the British Empire once did with their Australian colony. In Prometheus, we see David modeling himself after Peter O’Toole’s T.E. Lawrence both in fashion and affect. And, after a fashion, he follows in Lawrence’s footsteps in Alien: Covenant via the aforementioned genocide. (A failing of Alien: Romulus being an inability, if not complete unwillingness, to engage with the developed theme to its next step. I don’t acknowledge Alien: Resurrection.)

What’s more, we see the art built on this monstrous impulse. David takes the remains of Noomi Rapace’s Dr. Elizabeth Shaw and creates eggs. Eggs that would hatch into facehuggers that would impregnate Oram. With the return of the alien away from its Xenomorphic nature, we see again the sexual nature of its kills. When introduced in the final act action faux climax, it approaches two characters having sex in a shower. A scene seen in many a horror movie. But rather than go straight for the kill, the alien has its tail curl underneath the genitals of the couple, implicitly inviting itself into the sexual copulation without consent. (Further emphasizing this, when David tries to kill Daniels, he pins her down and tries to kiss her in a mechanical, loveless way.)

But the alien, for all its iconography, is not the central terror at the heart of the film. (Indeed, it takes over forty-five minutes for an alien creature to make an appearance.) That, again, is a creator (be it God, Space, or David) that has nothing but contempt for humanity. Who sees mankind as nothing more than a gnat. It’s telling that the film ends with David triumphant over the humans, having tricked the two most competent characters in the film (Daniels and Danny McBride’s Tennessee) into letting him in so he can create more art that can be admired for its purity rather than the messy failures humanity has turned out to be solely comprised of. As David ultimately puts it, “they are a dying species grasping for resurrection. They don’t deserve to start again, and I’m not going to let them.”

Humanity, for all that it has a herpes-like persistence, is not worthy of respect in the universe of Alien: Covenant. It is universally seen by the cosmos with nothing but scorn for daring to believe it could conquer the stars just because it’s old. There’s an air of Ligottian contempt at the heart of these films. (Or, perhaps more aptly, a cosmological cruelty seen in works like Blood Meridian or the Evening Redness in the West) One that can’t see consciousness as anything other than monstrous and full of evil. Where the best people fall to their own hubris and are thus easily manipulated by those with greater monstrosity. A cosmos that is utterly insane reacting to the vessels upon which it can understand itself with nothing but contempt. As William Blake once put it, “For never can true reconcilement grow where wounds of deadly hate have peirc’d so deep.”

In summation: God hates you.

(It’s worth noting that this is the central animus at the heart of Jonathan Hickman’s God is Dead. Co-created with writer Mike Costa (who would take over the book after the first six issues) and artist Di Amorim, Jonathan Hickman’s God is Dead explores a world where all the gods of every religion make themselves manifest and begin doing the kind of brutal murders one would expect from an Avatar Press book. On the whole, it’s not that good, save for the inexplicable appearance of Alan Moore explaining why he worships a snake puppet and Kieron Gillen doing a shitpost version of Hell.)

With this in mind, it is worth considering the previous experiences between alien and superhero in the comic book medium before diving into Aliens vs Avengers. The first of these, surprisingly, was Dan Jurgens and Kevin Nowlan doing Superman vs. Aliens in 1995. Like many Superman comics of the 90s, Superman vs. Aliens is a rather drab affair that errs more towards the Aliens narrative engine rather than the Alien engine. The most telling scene comes with the first chestburster moment, depicted as a full page spread. However, due to the bright lighting used by colorists Greg Wright and Android Images, the moment falls flat. Furthermore, Jurgens’ script spends far too much time on verbally expositing what happened, not letting the visuals speak for themselves. Characterization wise, Superman remains the authoritarian thug who frequently demands to be the one in charge of the situation and solves his problems through being the strongest flying brick in the room rather than coming up with a clever solution. A large portion of the comic is spent on Superman angsting over killing in John Byrne’s run, but never provides an alternative solution to what to do with the aliens before ultimately deciding to nuke them all and let god sort them out. Even the prospect of Superman getting a facehugger turns out to be a wet fart, which is ultimately what this comic amounts to. Following that was 1997’s Batman/Aliens by Ron Mars and Bernie Wrightson. Wrightson, being one of the great horror artists of the 20th century, is a natural fit with the Alien franchise. And yet, Ron Mars’ script feels like it was initially intended to be a Batman/Predator comics given the base plot is Batman and a team of mercenaries go to the jungle and fight the alien. What’s most interesting, however, is how much time the first issue of the series spends on the characters finding the aftermath of what’s happened. While Superman vs. Aliens felt as if things were being padded out, here there’s a sense of dread as this band of brothers walks unwittingly into certain doom. There are some parts that don’t work (the recurring motif of Batman’s parents being murdered that every Batman crossover feels the need to include is just as tiresome as it is here, though Wrightson does an admirable job depicting it), but there are some pretty damn good bits of horror that make it more in line with Alien than Aliens. In 2000, Ron Mars would do another crossover with the alien with artist Rick Leonardi in Green Lantern Versus Aliens. That things remain relatively domestic up to this point is somewhat surprising. Things naturally err more towards the Aliens side of things, but to a much better effect than Superman vs. Aliens by virtue of letting the atmosphere breath rather than providing multi-page infodumps about why Argo City isn’t Kryptonian. And while Rick Leonardi is no Bernie Wrightson, he’s able to get the job done rather well, creating an alien atmosphere that unsettles and excites. 2002’s Superman Aliens II: God War is a comic written by Chuck Dixon, years before he’d work with a Nazi publishing press, and drawn by Jon Bogdanove. It’s a New Gods comic and — much like ever New Gods comic that didn’t involve Jack Kirby, Grant Morrison, Tom King, or Ram V (I’ve not read Walt Simonson’s Orion or Rachel Pollack’s New Gods yet) — not a good one. 2003 would see the release of Batman/Aliens Two by Ian Edginton and Staz Johnson. Rather than feeling like a Batman/Aliens riff on Predator, here it feels like a riff on Predator 2, with its more urban backdrop and Batman investigating a growing body count. The work never amounts to anything more than serviceable, and the lesser end of serviceable at that. The most recent crossover between Aliens and the cape and cowl crowd is 2007 Superman and Batman Versus Aliens and Predator by Mark Schultz and Ariel Olivetti (shockingly, with letters by Todd Klein). Given that it’s an Alien/Predator comic, it’s perhaps best to let it slide before falling down a rabbit hole that can only end with me, much like Tom Servo, begging to be killed.

But perhaps the most notable crossover between the superhero and Aliens is Warren Ellis and Chris Sprouse’s 1998 one-shot WildC.A.T.s/Aliens. In many regards, WildC.A.T.s/Aliens might be one of the most important comics of the late 20th century. Not for its quality, which is of the caliber one might expect from an Ellis/Sprouse joint. That is to say it’s an extremely well made work of comics work that emphasizes the full scope of the science fiction ideas being engaged with, with clever word choices, inventive panel layouts, and a killer ending. But rather, the importance of what would normally be considered a disposable crossover comic comes in its role in things.

One of the key plot points in the comic is that the majority of Stormwatch, the comic series that launched Warren Ellis’ career, killed off when the aliens end up on the ship. Unlike previous crossovers, where supporting characters often are created wholesale for the books, these are preexisting characters. (The only exception is Superman versus Aliens, where Kara of Argo City is the lone survivor of the alien onslaught. But she is so far removed from what anyone going in would understand Kara Zor-El to be that she might as well be Lyla Lerrol or Luma Lynai or Cir-El. Also, she lives in such a way as to drain any what little narrative weight there was out of the ending.) As such, for fans who have been following the Wildstorm universe for years, seeing them all die horribly has an added weight the way nameless schmoe doesn’t.

This, in turn, would lead to the formation of The Authority (with artist Bryan Hitch), which would ultimately be the most influential superhero comic on the 21st century. The Authority took the implicit authoritarian idealism within the superhero genre and made it more explicit, having the heroes of the book essentially take over the world. In practice, a lot of their stories tended to be clever science fiction plots involving villains from beyond the stars seeking to conquer the world, ranging from an alternate universe England to a rather distressing take on a Yellow Peril villain. It’s a work that’s been responded to, rebuked, ripped-off, and embraced throughout the American comic book scene for the entirety of its existence.

But perhaps the most relevant influence — with regards to this article — is Jonathan Hickman’s massive run on Avengers and New Avengers. As a segment of Hickman’s Fantastic Four opus, Avengers restructures the team into specific units to combat various cosmic forces. On the whole, Hickman’s Fantastic Four run deals with the implications of the failures of the previous generation on the next and how said generation must evolve through these failures and how much responsibility the previous generation has to aid their children. As the Wizard, a significant villain of the run, puts it in his first appearance in the run, “Is there anything more disappointing to a creator than the failure of his creation? Why is it that my sons so thoroughly fail to please me? It is all so very disappointing. I know that a father is supposed to unconditionally love his children… But I can only find room in my heart for you and your current generation.” It is this thematic core that connects Hickman’s epic to the late era work of Ridley Scott in his bleak and pessimistic work such as The Counselor or Alien: Covenant. (Though not as aptly a line as “Is it playing God if you’re truly serious about creation? No, it’s not.”)

With The Avengers, Hickman explores a bleaker side of things. It breaks itself into two sides of an equation. The first side focuses on the main Avengers team reforming itself into a larger organization with subgroups within. These Avengers face off against cosmic forces that seek to change the world. Meanwhile, the Illuminati works in the background dealing with the even larger cosmological force of the entirety of the universe coming to a premature end. Being a group of great men, they have found themselves with no other option than to commit multiple genocides in the vain hope that the universe could be spared.

At the heart of this is the notion of what’s to be done when there’s no time left. When all the options presented are bad and you don’t have time to come up with any better alternative. It is a tragedy about two men as close as brothers coming to blows over an irreconcilable difference and the cruelty that results in trying to keep it buried. Of course, the thing of it is both of the men at the heart of the story — Captain America and Iron Man — are proud men who think they know what’s best for everyone involved and can’t conceive of alternatives to their monstrous decisions with catastrophic results. In the end, they are two men too busy fighting each other to see the giant object in the sky falling down to meet them.

In many regards, the ultimate climax of the run (baring Secret Wars, which ultimately errs more on the Fantastic Four side of things, thus acting as a rather weak rejoinder to the Avengers run while also being the best Event Comic published by Marvel) being a bleak summation of the inevitable failure of a project such as the Avengers. Consider Richard Jones’ Great Houses model and its view of the Avengers as resolving a broken system with “A system is best not changed.” While comics writer Kieron Gillen notes the cynicism of it, one can’t help but apply it to Hickman’s run accurately. It’s not until it’s too late that the players involved even consider rejecting the rules laid out to them by one of Hickman’s many albino women. The doom, as with so many tragedies, came from hubris.

It is natural, then, to see this run as a precursor to Hickman’s next major Marvel comic, House of X/Powers of X (hereon referred to as HoXPoX). While the X-Men run that spun off from it ended up largely being a wet fart, HoXPoX itself remains one of the most interesting comics to come out of the X-Men side of Marvel. It rejects many of the traditional tropes associated with the X-Men and instead reforges things into something a tad bit more complicated, working under the base assumption that the Mutants will never win. That things are eternally doomed right from the start.

This, of course, is a major idea of the modern day. As Blake scholar and literary critic Elizabeth Sandifer put it in her seminal work Neoreaction a Basilisk, “Let us assume that we are fucked.” We can likewise see this within the later filmography of Ridley Scott. Movies like The Counselor or House of Gucci explore settings where the rot has set in and any possibility of righteousness can only end in despair and hopelessness. All the Money in the World and Napoleon, likewise, showcase the decay of power in the wake of entropy, be it the monetary might of John Paul Getty or the military might of Napoleon Bonaparte. And Exodus: Gods and Kingsreframes the Moses narrative as a work of cosmological horror, emphasizing man’s fragility in the wake of God’s wrath. As Hickman himself puts it, “Everything dies. Empires collapse. Kings fall. And men perish. Worlds end.”

What’s more, these texts also highlight the crushing failure of these supposed Great Men of History. The Last Duel, for example, tells the same story of two Great Men having a fight from three perspectives, each less flattering than the last. The first presents a traditional story of a noble man righting a wrong perpetuated by a system that favors Lords. The second perspective shows this man to be little more than an unintelligent thug whose wife cheated on him and now the lord has to deal with the indignity of being accused of a heinous act. The final perspective — the woman at the heart of the matter — shows her husband to be only good for killing and the lord to be just as vindictive and cruel as he rapes her. There is no nobility, no heroism to be found in the mud. Nobody keeps their hands clean in war.

Returning to Alien with Prometheus, Scott finds himself opting to show the great explorers of the cosmos, great men like Peter Weyland who believe themselves to be the ones in control because they discovered something new. Not realizing that they only discovered something that existed long before we ever stumbled upon it and called it ours. Equally, the scientists who work for the Weyland Corporation find themselves acting in the name of finding God, believing they were called to this world because they found a message. But the context and purpose were lost long ago, and no one even considered its implications.

Similarly, the colonization ship Covenant sees a planet they barely researched, barely understand, and decides to conquer it instead of the world they spent years researching. It’s true that the Covenant crew experienced a massively traumatic event, but the decision was made because of a belief that what happened was divine providence and not simply a cruel accident. That this all makes logical sense. It is the belief that because they are sentient, humanity deserves to control the cosmos that dooms so many people.

Even David, for all that he succeeds, is doomed. While the obvious signs of psychosis are demonstrated in his creative drive to murder and experiment on corpses, what actually establishes his madness is far more subtle: he misattributes the poem Ozymandias to Byron rather than Shelly. Machines, for all their perfection, are just as culpable to entropy as the rest of us. Not even immortal AI can escape the one basic truth of existence: Everything dies. You. Me. Everyone on this planet. Our sun. Our galaxy. And, eventually, the universe itself. This is simply how things are. It’s inevitable…

Which brings us, at last, to Aliens vs Avengers. Considering the amount of time spent not talking about it, it is perhaps best to begin with the art of Esad Ribić. Coming off of his last collaboration with Hickman, Secret Wars (and actually given time to do the work without having to resort to several pages on pure white backgrounds), Ribić presents a bleak yet dazzling vision of the future. The use of crosshatching in particular tones away from the utopian visions one might assume a Marvel Universe future to have in favor of the bleakness highlighted in the Alien films.

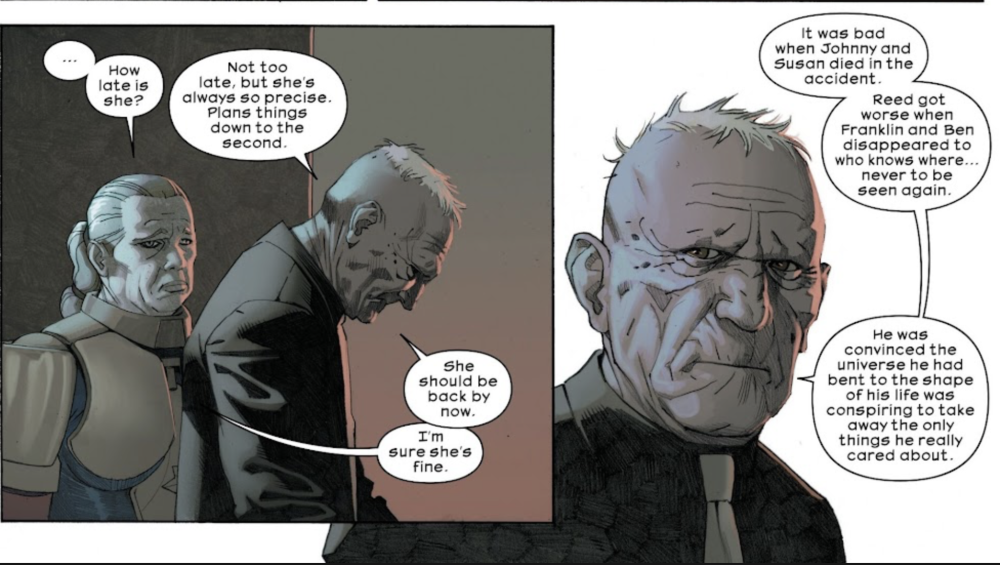

Perhaps the most notable thing about Ribić’s work in Aliens vs Avengers is his character designs. When tasked with creating a future for the various Marvel characters, Ribić delivers wholesale with a variety of age ranges that highlight the difference between the modern era of superheroes and this bleak future they find themselves within. While some of them are rather drably conceived of — most notably Wolverine, whose first appearance makes him look like his ears are drooping — Ribić’s character design works wonders. From the gracefully aged Emma Frost retaining her cold affect to Valeria Richards, who looks like her mother, but has her godfather’s eyes.

Of particular note is Bruce Banner. While the Hulk retains his youthful form, Bruce is a withered husk of a man brought low by decades of failure and ruin. We can see the pours and wrinkles on this sad, broken man. Indeed, it is safe to say that under Ribić’s pen, Banner is less a man and more a walking corpse. Furthermore, his dress sense of a pure black suit with only a white tie to differentiate it highlights the melancholy at the heart of a man we only briefly know.

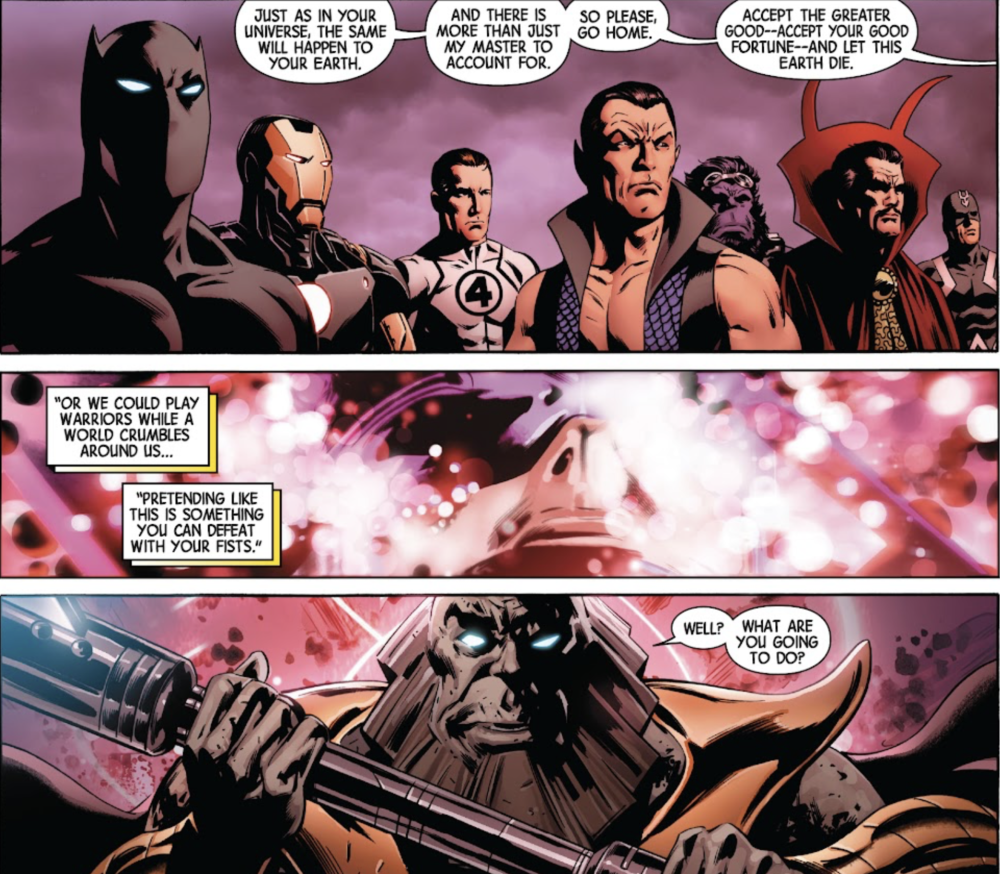

Equally, there’s the central characters of Hickman’s Avengers run: Tony Stark and Steve Rogers. It is quite amusing to see Stark — a man who started out as being kept alive by his Iron Man suit — once again kept alive by machines. In some regards, his design evokes that of Alex Ross’ Bruce Wayne in Kingdom Come, with braces around his arms and legs that help him remain as mobile as possible. Steve Rogers, in his scene stealing appearance, looks like Moses draped in the American Flag. Specifically, the Charlton Heston Moses with his determined, thousand yard stare. There is no stubborn brokenness to this man — in contrast to Hickman’s Avengers. This is the dream dying in a blaze of glory.

As for the Weyland Parasites (which, like many Alien crossovers, are never referred to as a Xenomorphs in-text, bar the recaps), Ribić does a stupendous job detailing their various forms and implications. It is to say absolutely nothing that these are quite terrifying creatures. Aided by colorist Ive Scorcina, Ribić delivers a cavalcade of horrors in what is largely an action narrative. One never feels safe watching wave after wave of aliens consume and overwhelm our heroes. Even the absolutely barmy idea of “What if Mister Sinister did things to the alien that gave it super powers” comes across as more horrific than a lesser artist might have done. At last, fulfilling the promise of Superman vs. Aliens in such a way as to highlight that comic’s shortcomings.

Note, for example, how Jonathan Hickman highlights the world in which the Aliens exist within. Rather than spend page after interminable page expositing the history of the world, Hickman opts to instead have little lines here and there that highlight the lived in nature of this future that never will be. There are some scenes where Hickman lays out the future in-depth, but they move at a decent pace with a panel flow that doesn’t make the reader feel like the narrative has stopped to explain what General Zod’s deal was in a seven year old John Byrne book.

Of note, we can see the influence of Grant Morrison in Hickman’s descriptions of the fall of humanity. (In particular, their runs on Zoids and Doom Patrol.) Rather than showing the full history of what has happened, we are instead given brief one panel glimpses in the fall of the great empires many Hickman readers have been following for over fifteen years. Much like in WildC.A.T.s vs Aliens, the weight of it being Iron Man or Spider-Man getting hit by a facehugger hits harder than if Tony and Miles seeing some random person we met three to seven pages ago would. (Though, I’m rather disappointed that Peter Parker doesn’t get hit with a facehugger, despite being the most John Hurt superhero of them all.)

In many regards, Aliens vs Avengers feels like the long awaited coda to Hickman’s Avengers. Where Secret Wars ultimately used the Avengers run to springboard yet another epilogue to Hickman’s Fantastic Four run, here we see the folly of great men brought with a little bit more grace. It asks what can be done when time runs out and there’s no fixing things and responds not with “Nuke ‘em all, let God sort them out.” Even if you assume that’s a valid option, it’s far too late for that to be a valid option.

Rather, Hickman suggests that the alternative to Weyland’s Parasites is creation. As Tony notes in the comic’s closing monologue, “I spent my life building things. Creating. I suppose, in a way, that makes me the antithesis of what we face. Some vile thing that lives to infect, consume, and destroy everything we are…and everything we have made. All that humankind seeks to leave behind… made ash in the mouth of an alien parasite.” The heroes resolve to save what they can, and find a way to survive. The empires of old have fallen, the systems of cruelty that they lived under have been upended. And we are left with the only decision: Change or Die.

Ironically, it’s Mister Sinister — a man who claims to represent evolution — who seems to represent the old ways of living. If the aliens here represent a regressive thought that pushes humanity away from any hope of continuance, Mister Sinister’s allegiance with them is a highlight of what he always was: a colonializing old bastard who utilizes the reactionary force of the aliens to dominate over all. A Great Man who, unlike the Tony Stark we follow, refuses to bow out and let the inevitable come. He fights death not to save people, but to prolong it for as long as possible. To defer the ending of things.

This is, of course, the natural state of superhero comics: the deference of an ending. The eternal second act where only the illusion of change exists. What makes Aliens vs. Avengers interesting is that it positions itself as the ending to the Marvel Universe. In the lead up to the series, Hickman alluded to a need to Alienize the Avengers (hence the future setting), but previous crossovers with Alien never felt the need to do such a drastic shift. They all remained within the relative present of their respective characters.

Which raises the most pertinent question when it comes to a crossover: What does bringing two texts together reveal and highlight? We’ve seen things from the perspective of the Marvel Characters, but what of the Aliens? Unlike the previous crossovers between superheroes and Aliens (and, indeed, unlike the other crossovers involving Aliens in general) there are recurring characters from the movies seen within this comic beyond the titular alien: David and the Engineers.

With the Engineers, we see them in a minor role within the miniseries as the cause of the other set of aliens attacking the cosmos with the purpose of cleansing it of all life. This tracks with the actions we see the sole living one commit in Prometheus, looking at the human race that discovered it and, finding it wanting, killing them all on sight.

This is, of course, a rather simplistic characterization, and one that is apt for Prometheus. There is, after all, a reason why it is not the distinct narrative mold from which Alien stories can sprout from, despite being the progenitor of that mold. It is worth noting, given how much I waxed on about it, that Prometheus comes at a transitionary point within Ridley Scott’s filmography. On the cusp of terminating its gestation period, perhaps. But transitionary nevertheless. God may hate man, but there’s still hope.

With the Weyland Parasites, it’s notable that things ultimately hue towards the Aliens interpretation of things. This is to be expected as Aliens was the one that all the spin offs and continuations come out of. The original Alien was a rather closed haunted house story that didn’t leave any room for a follow up. Yes, Ripley survived the end of the movie, but there wasn’t anywhere to really go with the material that wouldn’t inevitably be either a lesser rehash of what we had seen in the original movie or Alien Takes Manhattan.

Aliens, meanwhile, does provide a narrative engine for stories to follow after it. It does so by selling out the soul of the series to militarism, but it does so nonetheless. After all, it wouldn’t make sense for the Predator ship in Predator 2 to have the skull of The Thing from another world or a pod from Invasion of the Body Snatchers. They’re aliens, sure. But their narrative logic doesn’t match. Predator and Aliens are action movies, those are horror films. (Hence the trailer for Predator: Badlands highlighting the skull of an alien from Independence Day and not The Empty Man.)

So it makes sense for the Weyland Parasites to be more an animalistic horde that cannot be stopped, no matter how well armed you are or how well prepared you are. They will kill you all. Indeed, a lot of the narrative of Aliens vs Avengers feels at home in the Aliens mold of things. Many of the characters go out in a blaze of glory, fighting off the various creatures that attack them. And the story ends on a hopeful note of ambiguity, wherein everyone is preparing to travel off in the unknown thanks in small part to the remnants of the last remaining empire.

The problem is that Aliens vs Avengers is not an Aliens story. This is plainly seen on both the artistic and script writing fronts. Artistically speaking, Esad Ribić draws the cosmos with a harsh edge. The colors Ive Scorcina provides are not the warm blues of the opening shot of Aliens, a cosmic swirl of oceanic delights. But rather a bleak darkness. When there is light from the stars, it’s a piercing brightness like looking into the sun. Even the action sequences are not the thrilling adventure fare typically seen in superhero comics or military science fiction.

One could argue that the art is hueing more towards the style of the original Alien with its horror aesthetics. However, the problem there is that the original Alien wasn’t as clean as Ribić’s art style. The aesthetics of the film were more along the lines of a working class ship on the brink of disrepair. Even the common area where the crew hang out is full of little pieces of trash. Furthermore, the aesthetics of the ships are more in line with traditional science fiction of the early 21st century with clean edges and sleek design philosophy as opposed to the gothic architecture or even the giant gun in space that the previous films provided.

No, the Alien film Aliens vs Avengers feels the most in line with is Alien: Covenant. Thematically speaking, this makes sense. Throughout Hickman’s career, he has explored the thematic implications of technology — in particular, Artificial Intelligence — on the human condition and how it can transcend humanity. Indeed, the largest existential threat within HoXPoX and his later X-Men run wasn’t the various human organizations or the infighting amongst the very bad people being brought into utopia, but rather sentient AI that would transcend the human form. Even earlier works like the lamentable Transhuman highlight the ways in which technological advances can lead to horror.

The problem is that Hickman is not the right sort of writer to get to do an Alien: Covenant. Yes, Hickman is capable of demonstrating bleakness within his work. Transhuman ends with the human race subsumed by a more rapidly evolving species that finds humanity wanting. But the tone it provides is that of a man rushing towards you so he can shit in your mouth. Alien: Covenant’s bleakness, meanwhile, is more akin to a slow realization that you’re in the same room with a madman and all you can do is scream, even though you’re fully aware that no one can hear you. Yes, there’s a pathetic nature to the various humans who fall, but it’s presented as an object of horror as opposed to a punchline.

Conversely, Aliens vs Avengers approaches the fall of empires with a degree of sadness. There’s an air of mourning to the death of space utopianism at the hands of the alien. We are given valiant last stands with a semi-hopeful ending instead of having our hubris thrown back at us. The violence is unsettling and painful, never shying away from each and every gory detail.

But moreover, there lies the central axis of the horror and, subsequently, the third character brought over from Alien: Covenant: David. The thing about David is that, in the film, he is an artist. His creations of horror are framed as an artistic pursuit for the sake of creation. To further drive home the point, we see some of his sketch work and it’s literally the work of H. R. Gieger, the designer of the original alien. When he first encounters a chestburster (finally with translucent skin), David is in awe of the creature, demonstrating movement that the alien follows.

In the comic, David is nothing more than his destructive impulses. There is no art to his destruction, only the extermination of a lesser race. (Ironic, given an early antagonistic figure in Hickman’s Avengers is also a creator.) We do not see David cultivate his Weyland Parasites into something more, like Mister Sinister would later do. Instead, he’s tossed aside as a corporate raider who happens to be an android from another universe.

It’s not that the comic is bad. It’s pretty dang good. But it doesn’t live up to its potential. Or, as John Logan and Dante Harper put it in their screenplay for Alien: Covenant, “When one note is off, it eventually destroys the whole symphony.” One wishes the comic was closer to Alan Moore and Gabriel Andrade’s Crossed +100 or Grant Morrison and Chris Burnham’s Nameless instead of Warren Ellis and John Cassady’s Planetary or Mark Millar and Bryan Hitch’s The Ultimates. The end result is not without merit, just a structural perfection matched only by hostility.

“The problem is not that there is evil in the world. The problem is that there is good. Because otherwise, who would care?”

-Noah Hawley and Bob DeLaurentis, Aporia

The Aliens Vs Avengers TP is available this month

And check out the Beat’s most recent comics reviews!