by Emilio Cirri

From September 25 to 28, 2025, the Andalusian city hosted the first edition of the San Diego Comic Con Malaga: some reflections and an assessment (from a European perspective).

From September 25 to 28, 2025, the first highly anticipated international edition of San Diego Comic Con took place in the Andalusian city of Malaga. Within the setting of the FYCMA (Palacio de Ferias y Congresos de Malaga), for four days one of the most important conventions in the world offered a taste of its atmosphere, its vibes, and everything that makes it famous. It’s an event that inserts itself directly into the panorama, not only of Spanish comic conventions, but also of European ones, with a three-year project running until 2027 that aims to establish a new focal point for fans of pop culture.

Although I have never personally attended the original San Diego Comic Con (still one of my unfulfilled dreams), my experience with some Italian and European conventions allows me to provide a different perspective on an event that, while having an American backbone, must also engage with a very different approach to this kind of convention compared to the USA. And so here follows an outline of strengths and weaknesses.

Guests and Program: Blessing and Curse

The guest lineup of the SDCC-Malaga certainly lived up to the expectations of fans and enthusiasts: in terms of cinema, names included Arnold Schwarzenegger, Jared Leto, Elle Fanning, Dan Trachtenberg, Luke Evans, (David from Beverly Hills 90210), Natalia Dyer (Nancy from Stranger Things), Aaron Paul (Jesse Pinkman from Breaking Bad), Gwendoline Christie (Brienne of Tarth from Game of Thrones), as well as Spanish actors very well known in the United States such as Dafne Keen (X-23 in Logan and Deadpool & Wolverine) and Taz Skylar (Sanji in the One Piece live action). As for comics, there were international artists such as Peach Momoko, Matt Fraction, Kelly Sue DeConnick, Jeph Loeb, Joe Kelly, Martin Simmonds, Sara Pichelli, Jim Lee, and C.B. Cebulski, alongside great names from Spanish comics (Emma Rios, Carmen Carnero, Pepe Larraz, David Lopez, Fernando Blanco, Jorge Jimenez, and many more). Not to mention guests from animation, video games, and content creators. An undeniably impressive roster, although it left a bitter taste that some of them (I am not referring to the actors, but to artists and authors such as Jim Lee, for example), despite being announced as main guests, only appeared for a single day—something that was not clear until just a few days before the start of the event.

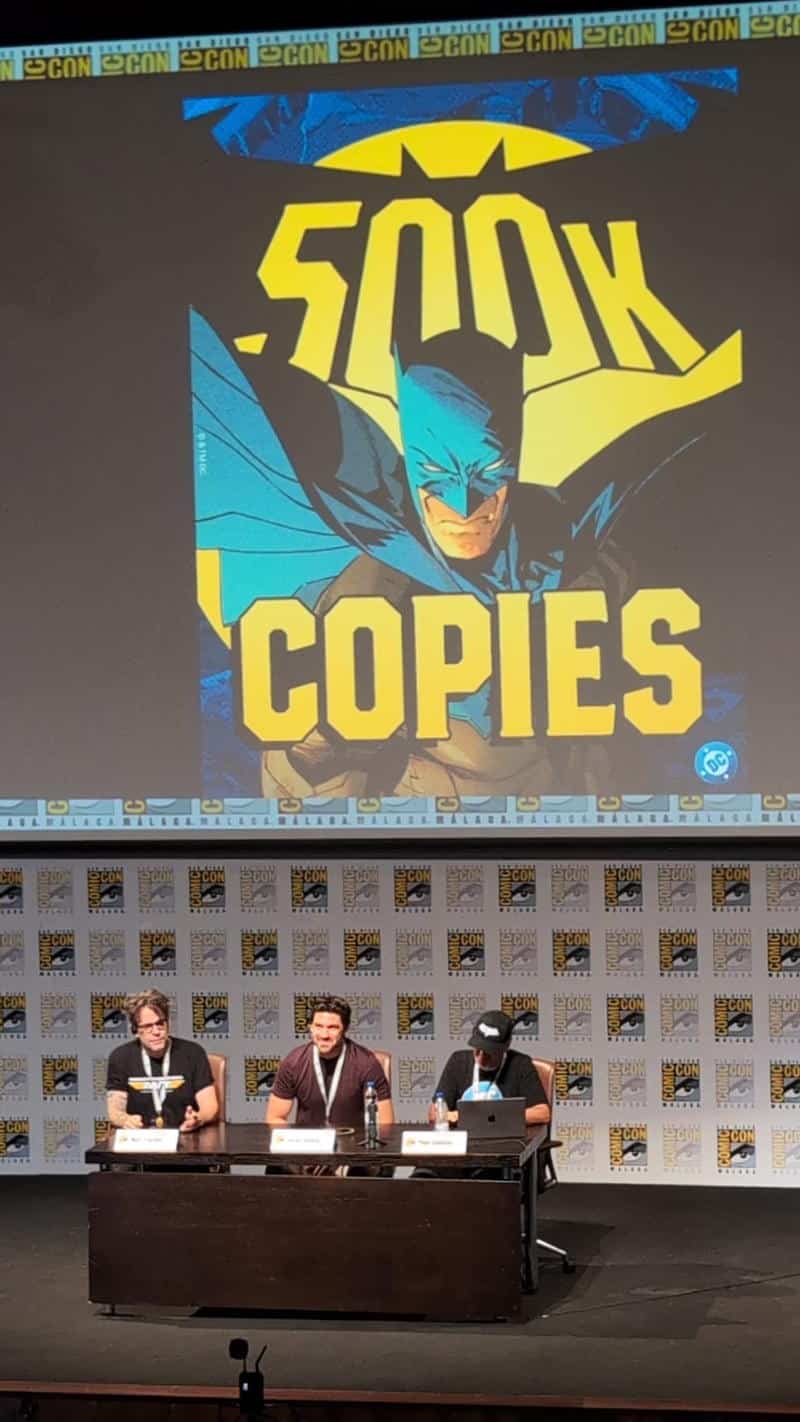

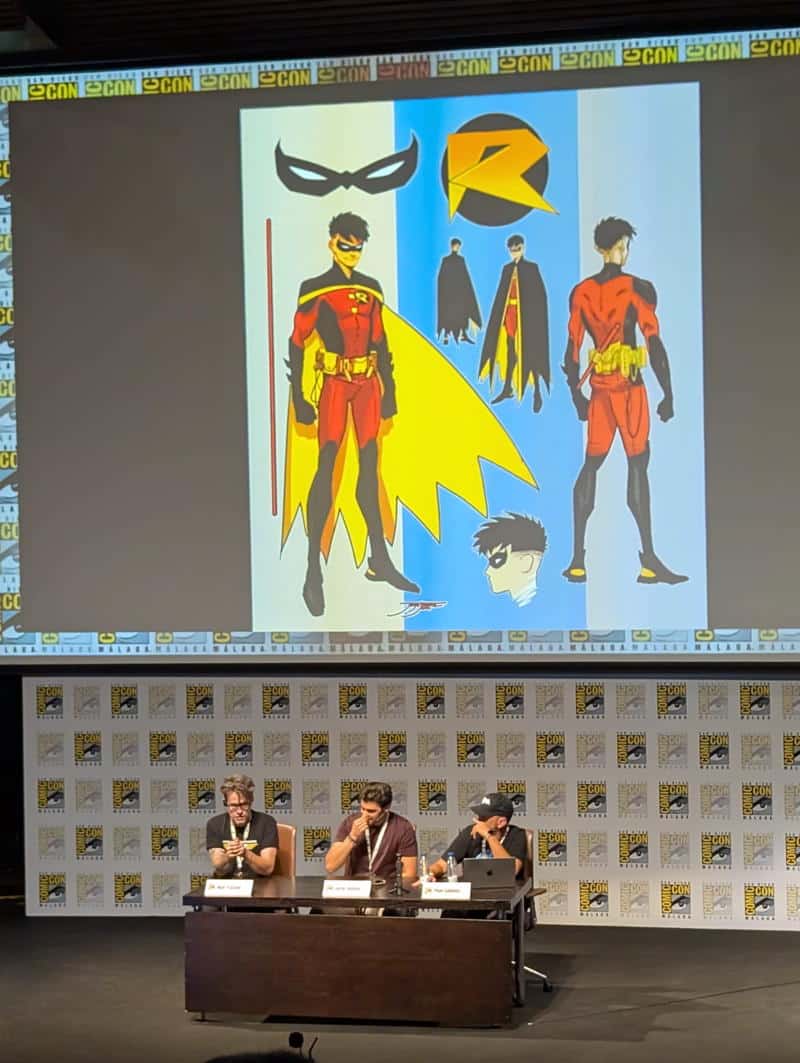

Passionate fans were able to meet all these guests directly or hear them speak on stage thanks to a program hosted in large or very large halls (Hall M, dedicated to the biggest events such as the presentations for Tron: Ares, Predator: Badlands, or the highly attended Arnold Schwarzenegger masterclass, could seat 3,000 people, while the others ranged from 600 to 800). These were often stormed and filled with very enthusiastic fans, an experience not commonly found among European audiences. The program, balanced between more technical sessions, a good amount of space dedicated to Spanish professionals, and more mainstream moments, offered previews (such as the unveiling of Minotaur, Batman’s new enemy, or world premieres of certain films) and generally met expectations, despite some issues with AI-powered translation via QR code and smartphones, which was not always reliable.

In contrast to a well-constructed program capable of combining in-depth discussion with hype, the management of public interactions, especially for signings, was not as well handled. Although the website listed guests and the stands where they could be found, without adequate preparation before the convention it became practically impossible to understand who was signing what and when, since often the stands did not display schedules and sometimes not even the names of who would be present. This information was easier to find on the websites of publishing houses or authors’ agencies. In some cases, moreover, the location of the stands created crowded bottlenecks (something I will return to shortly), adding to the discomfort of queuing in an already dense situation.

This management, even more than the presence of international authors, ended up penalizing lesser-known Spanish authors who are more tied to the local market: although present in large numbers (comparable to what one might find at Spain’s most important comic festival in Barcelona), the lack of visibility of their works and their scheduled appearances caused them to be overshadowed by other elements. And while it is true that San Diego Comic Con has a very strong U.S.-centric orientation, doubts remain about how the presence of these authors was actually conceived.

All of this was compounded by a somewhat slow and cumbersome handling of press communications: the festival’s announcements, managed primarily through social media and much less through press channels, were inconsistent, as they were held until the end of July (just under two months before the event) so as not to overlap the original San Diego Comic Con, which somewhat overshadowed them. Nevertheless, the efforts of the press team should be appreciated: they had to make the best of a difficult situation, and they did excellent work at the convention, always available to all journalists to meet every need, including interviews with guests, in the context of an extremely tight schedule.

Main Hall: Between Collectibles and Photo Opportunities, Comics get squeezed

The organization of the Main Hall, from a European point of view, may appear unusual: in almost all European festivals and conventions, even the largest and most comprehensive ones (such as Lucca Comics and Games), comics, merchandise, video games, and everything else are usually, if not strictly separated, at least grouped into “thematic islands,” so to speak. At San Diego Comic Con in Malaga, however, apart from the artist alley—which was indeed grouped in one specific area (though unfortunately not optimally organized, as mentioned earlier)—everything else was mixed together, with no distinction made between different sectors.

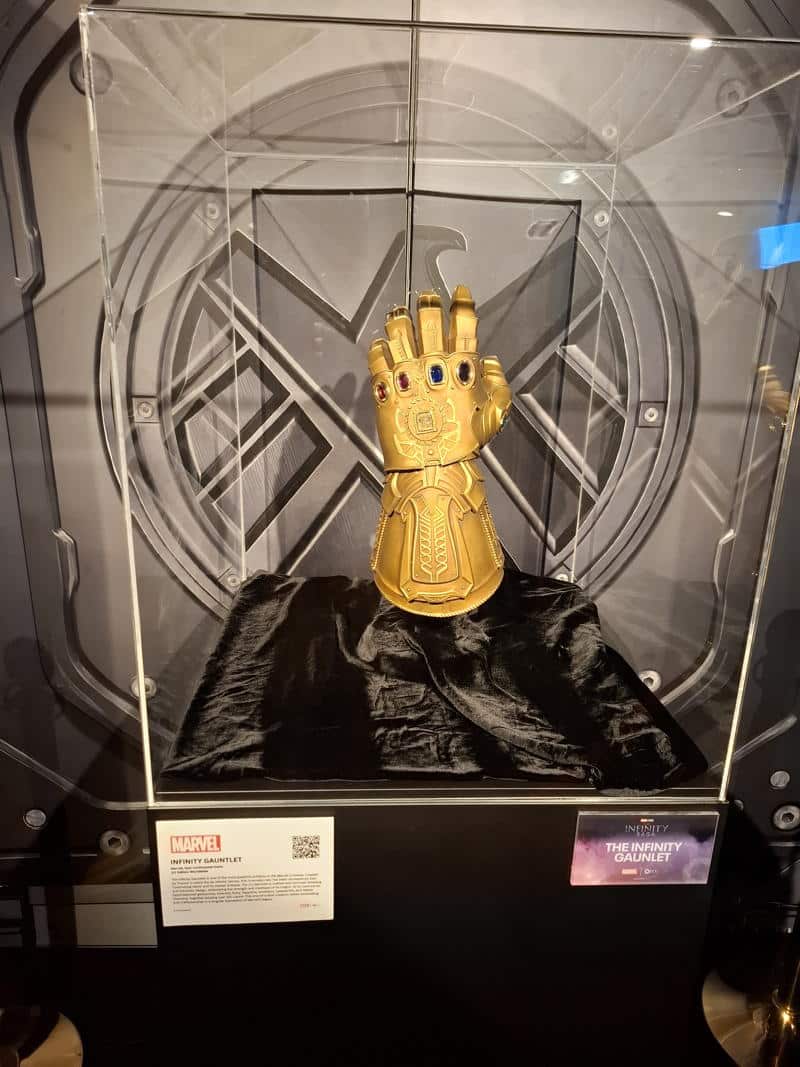

This choice certainly allowed visitors to come into contact with many different areas and perhaps new experiences, exposing comics (according to a couple of vendors) to a wider audience. At the same time, however, the comic stands—even those of the (few) Spanish publishing houses—were relatively small and not particularly well stocked (with the exception of Penguin Random House Spain and the comic shop Comic Stores). The bulk of the floor space was occupied by video games, merchandise (with some stands visibly selling non-official material), and above all large booths dedicated to photo opportunities, such as those for Tron: Ares (where visitors could take a picture on the film’s motorcycle), Toy Story (with Andy’s bedroom recreated from the toys’ perspective), Predator: Badlands, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. English-language comics in their original form—whether single issues, trade paperbacks, or hardcovers—were, surprisingly, absent, except as copies to be signed and slabbed for collectors, with the famous grading company CGC also present.

It is true that conventions are, first and foremost, opportunities to gather, to share experiences, and to be able to say “I was there, I saw and did things,” and while fans did attend panels and flock to signings. But the impression is that the focus was more on the fleeting “experience,” on collectibles (the scramble for the exclusive Funko Pop produced for the occasion quickly went viral), and at times on speculation (with convention merchandise already resold on eBay at inflated prices), than on building a community and placing at the center not only the commercial but also the cultural and social value of pop culture and entertainment. And while this is true today of many conventions of this kind—even in Europe—in this case the impression was even stronger and more pronounced.

Organization: Between Complaints and Disruptions

I have left the most discussed and painful point for the end of this report: organization. Browsing online, on news sites as well as on social media, one can find hundreds of videos and comments about the Comic Con experience, especially during the weekend: endless lines (the most widespread pun being Cola-Con, literally “Con of queues”), excruciating waiting times (up to 3 hours just to get into the main hall), events impossible to attend due to “overbooking,” all combined with particularly hot days. All of this resulted in formal complaints being filed with the OCU (the Spanish Consumers’ Organization), with more than 200 reports concerning every possible kind of problem.

Among these, one issue in particular—raised even before the festival by FACUA (another consumer protection association based in Seville)—was the ban on bringing in outside food and drinks, which forced attendees to rely on the internal food offer: a single large outdoor stand serving questionable-quality food, with little variety and at very high prices. This, combined with the entrance fee (€50, a price far beyond the European convention market), infuriated the public. This ban, although never officially revoked (yet again, a lack of communication), was in practice not enforced by the organizers after the FACUA complaint. According to the association, since the festival is not a gastronomic fair, it could not impose such a ban without violating certain national laws. I myself was able, on the second day, to bring food and water from outside without being checked. And after all, how could every single attendee have been controlled, with a crowd of 120,000 people over four days? Still, this remains quite unusual for a festival of this kind, as no European event imposes such a rule (except for the common restriction on eating near the stands).

At this point, I’d like to take a step back: the organization began with a very ambitious goal, and of course its brand resonated with fans (myself included), perhaps beyond even the most optimistic forecasts. Starting with an audience of 120,000 people (originally 60,000 were expected) is certainly no easy task, and organizational difficulties were to be expected. In some areas, they managed as best they could (anyone who has attended a decades-old event like Lucca Comics, which has hosted up to 320,000 people in five days, knows what this means). At the same time, comparing Friday and Saturday, the difference was striking: on Friday, despite a significant turnout, everything proceeded relatively smoothly, and people, though facing queues and wait times, were still able to enjoy the event more. On Saturday, with a perceived crowd five times that of the previous day, the situation became hellish—even for those with a press pass, which acted as a sort of passpartout and allowed shortcuts unavailable to others. Queue management held up largely thanks to the composure of the attendees themselves, aptly called “the real heroes of the Con” by Antonio Banderas during Arnold Schwarzenegger’s masterclass presentation. Perhaps the sustainable size of this Comic Con, if it keeps these spaces, is closer to Friday’s attendance; in that case, admissions will need to be limited, as they probably should have been already this year. Alternatively, the spaces must be profoundly rethought—perhaps with additional temporary structures (on the available outdoor area of 22,000 square meters) and a better entrance system.

As mentioned earlier, communication also needs serious reconsideration, since up until the very last days and even during the convention, many things were communicated poorly, late, or not at all.

One positive note, and not a trivial one: the transport system, with shuttles to and from the city center, worked well, providing excellent service under challenging conditions.

All of this must be considered alongside the ticket price (€50), which is significantly higher than the European average (given that one of the continent’s largest festivals, Lucca Comics and Games, in 2025 offers tickets between €20 and €35), and which is expected to rise further in the next two years of the event, reaching €80—on top of very high and often unregulated accommodation prices (a common issue during such events).

This year’s experience, therefore, while showing positive aspects and great ambitions, must lead the organizers to reflect on many issues: we shall see whether in the next two years San Diego Comic Con Malaga will prove to be a failed experiment or whether, as all the potential suggests, it will become a new, major, and rewarding event for pop culture fans across Europe.

Born in 1990 in Florence, Emilio Cirri has been living in Jena, Germany, for the past decade. True to the best comic-book tradition, he’s a chemistry and biology researcher by day and a comics writer by night. An omnivorous reader—ranging from manga to essays, with plenty of superheroes and graphic novels in between—he has been contributing to Lo Spazio Bianco, one of the most important Italian websites on comics (https://www.lospaziobianco.

Photos by and © 2025 Emilio Cirri