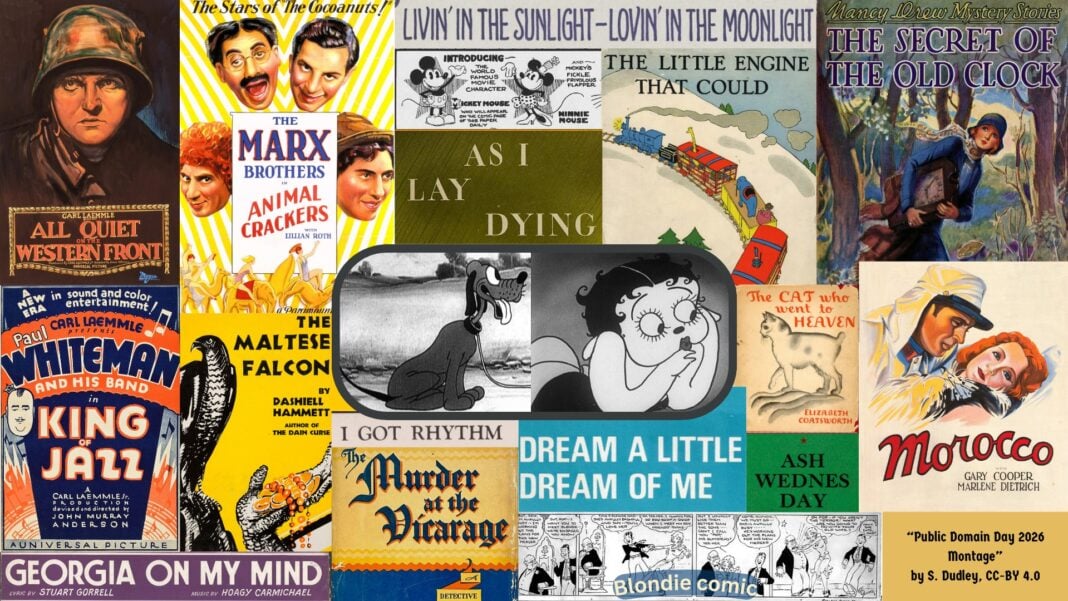

In just two days, when the calendar tips over into 2026, a number of beloved characters and works of art will lose copyright protection in the United States and enter the public domain. While this means you can print and sell your own versions of The Maltese Falcon and Animal Crackers, what’s arguably more important is the way the public domain fosters future creativity. When a character falls into the public domain, anyone can use them in derivative works, allowing for things like Wicked, featuring L. Frank Baum‘s characters from the world of Oz, or Jim, Percival Everett‘s award-winning novel based on the characters from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, to exist.

Of course, artists wishing to dip into the public domain for inspiration also have to be careful: while “Rover” is public domain, it’s likely Disney will continue to guard any version of Mickey Mouse’s beloved dog that is named Pluto for another year. Early editions of books featuring characters like Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys were sometimes rewritten or updated to reflect changing times, meaning that the version of The Secret of the Old Clock at your local library might still have copyright-protected elements.

In particular, the folks behind Fleischer Studios have signaled a willingness to fight over Betty Boop, who is headlining many of this year’s biggest “Public Domain Day” stories.

“In 1930, a precursor of the Betty Boop character appeared in the first cartoon of the ‘Talkartoons’ series, ‘Dizzy Dishes.’ Only over a period of years did that character evolve into the character we now recognize and call Betty Boop and become the distinctively different and independently protectible expression of the character in use by Fleischer Studios today,” CEO Mark Fleischer said in a statement. “While the copyright in the ‘Dizzy Dishes’ cartoon may fall into the public domain in 2026, this does not affect Fleischer Studios’ copyright in the fully developed Betty Boop character Fleischer Studios created in subsequent cartoons and other uses and continues to use today. Fleischer Studios’ copyright in that character will therefore remain in force for some years to come, as will Fleischer Studios’ copyrights in the many subsequently revised and modern versions of the Betty Boop character and related elements.”

By “full-developed,” Fleischer is trying to thread a needle common to the public domain conversation. Early versions of Betty Boop, Mickey Mouse, and other characters are often vaguely defined, and only begin to take on some of their most recognizable features once they start to become popular.

A popular example: when Superman’s first appearance enters the public domain in 2033, that version of the Man of Steel will be able to “leap tall buildings,” but not fly. The hero was first depicted as flying under his own power in the 1940s. Of course, Fleischer Studios depicted Superman as flying in 1941, a few years before it would ever happen in the comics, and the Fleischer Superman cartoons are already public domain, so that’s an argument we’ll all be having in a few years.

Copyright law allows for aspects of public domain characters to remain protected if they are “non-trivial,” which is a broad and ill-defined term that allows each individual case to be evaluated on its own merits. Each new story featuring a recurring character can still be copyrighted in and of itself, even if the characters is in the public domain, which complicates the question.

So– to continue with the previous example — if Superman’s first documented flight in the comics was in Superman #30, published in 1944, DC could argue that the introduction of flight to the character is a non-trivial change that should be protected for six years beyond the 1938 first appearance of the character. Other creatives hoping to use a flying Superman could argue that the 1940 radio show, 1941 cartoon, and other instances of Superman flying could supersede that, and that since those elements are in the public domain, Superman’s power of flight should be as well. And in any case, it could plausibly be argued that the power of flight is a trivial change from a character who could previously leap impossibly long distances.

Similarly, early Mickey Mouse cartoons depicted him as kind of a prankster and mischief-maker rather than the lovable pal he would evolve into. Betty Boop’s earliest appearances feature dog ears, since she was originally designed as a love interest for an anthropomorphic dog. It’s very likely, given the statement by Fleischer, that any Betty Boop story that doesn’t feature the dog ears will be subject to pretty harsh scrutiny until at least 2028, when the first non-dog Betty cartoons will start to enter the public domain.

While personality traits like Mickey’s or fairly general changes like Superman’s shift to flight are pretty debatable, it’s likely Fleischer could make a strong argument that the shift from anthropomorphic animal into human woman is not a “trivial” change.

Of course, if that’s the path they’re going to take, expect the next couple of years to be rich with Betty Boop furry art.

Equally relevant is the fact that the actual name “Betty Boop” wasn’t used until late 1931, meaning that (like Pluto) her likeness can be used but it’s unlikely a derivative work could get away with calling her Betty Boop in 2026. While you might think 1931 plus 95 years means 2026, copyrighted works are protected in the public domain by calendar year. Two works — one published on January 1, 1931, and one published on December 31, 1931 — would both enter the public domain on the first day of 2027, not 2026.

There is already some question as to whether the character herself may have fallen into the public domain due to non-renewal in the past. While modern copyright laws are automatic, and continuous, copyrights from before 1964 have to be renewed in order to enjoy the full 95 years of copyright protection. In 2011, 2011, Duke University reveals that an appeals court “definitively held that Fleischer did not own the copyright in the Boop character,” owing in part to the current company being a distinct legal entity from the original Fleischer animation studios. The exact nature of Fleischer’s continued claims to full ownership of the copyright is unclear and dubious, according to Duke Law. This is reminiscent of other characters whose copyright holders continue to assert continued ownership after they become public domain, like Tarzan and Zorro.

Public domain characters can also continue to enjoy trademark protection, which is more complex. When the name “Mickey Mouse” falls into the public domain, Disney can still protect Mickey-branded items under certain circumstances. The idea of a trademark isn’t to protect the specific intellectual property, but the brand and its reputation, and to prevent any confusion on the part of consumers. Basically, you can make a Steamboat Willie horror movie, but you have to be sure people know it’s not a Disney movie.

This is why, despite the original Captain Marvel being bought up by DC, they took pains to use “Shazam!” in branding rather than his actual name. By the time DC bought up Fawcett’s characters, the trademark for “Captain Marvel” had lapsed, and Marvel had created their own version so they could take and keep the name. Inside the comics, he was called “Captain Marvel” until the 2011 New 52 reboot…but his long-running comic The Power of Shazam! was called that for a reason.

Again, Fleischer’s statement asserts their trademark, and suggests they will protect it as it pertains to merchandise and derivative works pretty aggressively.

“[T]he Betty Boop character and brand, with worldwide name and imagery recognition, will continue as a protected global ambassador for Fleischer Studios and its licensees’ entertainment content, merchandise, and other goods/services and activities,” says the studio’s statement.

We’ve seen what was done with Popeye, Mickey and Winnie the Pooh. I fear what is going to happen to poor Betty and the rest.

So what will it be, 2039 or so we once again get to see a vigilante willing to kill named The Bat-Man? Cool!

Comments are closed.