[Previous chapters: Introduction, 1 – Prehistory, 2 – Marvelman Rises, 3 – Marvelman Falls, 4 – Intermission: 1963 to 1982, 5 – Prologue to Warrior]

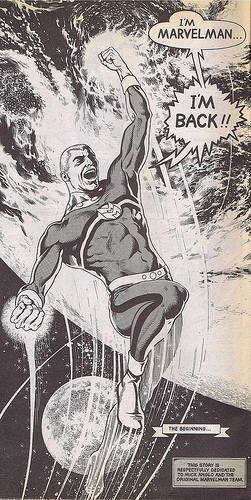

Moore’s attempt to place his silly fifties superhero in the cynical eighties was pitch-perfect, and breathtaking to watch unfold. Probably the most memorable line in those early issues for me, a definite sign that this strip was going to take us places we hadn’t gone before, as well as a foretaste of themes that would later appear in work like Watchmen, was in the series of captions in issue #6, accompanying Marvelman’s aerial fight with Kid Marvelman over London, that says,

They are titans, and we’ll never understand the alien inferno that blazes in the furnaces of their souls.

We are only human.

We will never grasp their hopes, their despair, never comprehend the blistering rage that informs their every blow.

We will never know the destiny that howls in their hearts, never know their pain, their love, their almost sexual hatred…

…and perhaps we are the less for it.

It was when I read the words ‘their almost sexual hatred…’ that I knew that there was something new here, a complexity and depth that I’d never seen before in a comic, something I very much wanted to see more of.

As the months passed, and more issues of Warrior appeared, it quickly became evident that Marvelman was the most popular strip in the magazine, closely followed by Alan Moore’s other strip there, V for Vendetta. It must also have been well thought of editorially, as it was virtually always the first strip in Warrior, just after the contents page. The strip started to run into problems early on however as, although Garry Leach was only drawing between six and eight pages an issue, he was taking the whole month to do so, to the exclusion of any other work. Eventually he decided that he couldn’t continue to work like that, so he gave up the strip. Fortunately, there was someone else waiting in the wings.

However, there was at least one good thing to come out of all the confusion. One of the strips in the Summer Special was a one-off Marvelman story called The Yesterday Gambit, a story that was not part of the ongoing continuity established in the previous three issues, but rather set a few years in the story’s future. The ten-page story was composed of three different parts, drawn by three different artists: Steve Dillon, Paul Neary, and Alan Davis. Alan Davis was at the time the artist on Marvel UK’s successfully relaunched Captain Britain strip, then running in Marvel Super-Heroes. The writer, Dave Thorpe, had left the strip, and Davis had suggested bringing Alan Moore on board as the new writer. Moore in turn suggested to Dez Skinn that Davis would be a good replacement for Garry Leach on Marvelman and, although Skinn had reservations about the only two superhero strips in British comics being written and drawn by the same two people, he none the less went along with Moore’s suggestion.

To ease Davis in, and so as not to have too sudden a change from Leach’s artwork to Davis’s, Davis only did the pencil art for issues #6 and #7, with Leach inking over his work. Indeed, Davis originally thought that he was only coming in as a stand-in artist to allow Leach to catch up on his own work, which may well have been the case initially, but it became evident that Leach wasn’t coming back to Marvelman, and Davis found himself the permanent artist on both pencils and inks. In private correspondence with Davis, he told me:

When I was first asked to pencil Marvelman I never regarded myself as Garry’s long term replacement – I was only asked to pencil two issues for Garry to ink. I believed I was simply doing some donkey work to help Garry make up time on deadlines – perhaps it was a test to see how I coped. When I was subsequently asked to pencil and ink an issue, and then another, I still made no long-term commitment. Firstly, I don’t know what led to me being asked to draw Marvelman or who championed my involvement – I have heard various contradictory explanations – but I was well aware that I was never Dez’s first choice – and I didn’t blame him, I was an utter novice – there were any number of seasoned/recognised artists Dez could have chosen IF he had more financial backing.

Secondly, it was never ‘work for hire’ because I sold a ‘first English language publication only’ use of my work which guaranteed that I retained ownership of the pages I drew and the images, and character designs, they contained. This is one of the common confusions with people not understanding the difference between the trademark and character copyright as opposed to the ordinary creative ownership of any work originated by the creator – and the variety of ways parts of those rights can be sold.

When it was finally made clear that Garry was going to quit Marvelman, to work on Warpsmith, I said I would only agree to continue drawing Marvelman if I was given an equal percentage of the trademark and character copyright Dez, Garry and Alan claimed to own. Each gave me a percentage that made me an equal quarter partner. Remember, Warrior was paying £40 per pencilled and inked page as opposed to £80-£95 from Marvel UK or 2000 AD so working for Warrior was a gamble to secure an equitable, or enhanced, payscale through royalties.

By the time Garry Leach was finished with Marvelman he had only actually drawn twenty pages of art, and inked a further fifteen pages of Alan Davis’s pencils. None the less, he established the look and the tone for the art that was to follow. Leach’s art wasn’t completely gone from the pages of Warrior, however, as there was a two-part Warpsmith story called Cold War, Cold Warrior, written by Alan Moore and drawn by Leach, which ran in issues #9 and #10. The Warpsmiths, an alien race co-created by Moore and Leach, would turn up in Moore’s Marvelman stories, beginning in the flash-forward story in the Warrior Summer Special, and would particularly feature in Olympus, the third and last book of Moore’s run, where they, along with their ancient enemy, the Qys, would play an important role.

The Warpsmiths, and more particularly their sworn enemy, the Qys, play a very important part in Moore’s version of Marvelman. He had used the name Qys for a ‘starhopping alien race’ in perhaps the earliest comic strip story he wrote, the four-page Once There Were Dæmons, which appeared in Embryo #5, published by the Northampton Arts Lab, edited by Moore himself, and cover dated 18/11/1971, which would have been his eighteenth birthday. In the same story there is mention of a character who is ‘a blind warper from Algol’, so it would seem that the Qys and the Warpsmiths may have been at the back of Moore’s mind, waiting for a home, for some ten years or more before he used them in Marvelman.

The superhero genre is an offshoot of science fiction (amongst other things), and good sci-fi usually runs according to certain established laws. To my mind the most important of these is that the fantasy in any given story should stem from one divergence from reality. […] If my Marvelman is going to fit logically into a gritty and realistic nineteen eighties then the character should at least have some pretence of credibility. Thus all the fantasy in the strip stems from one point… the crashing of an alien spacecraft in 1948. Everything else follows on from that.

Therefore, the modern version of Marvelman is inextricably bound up with the Qys and their technology, concepts that belonged wholly and solely to Alan Moore and Garry Leach. Much later on, I’ll be referring back to this, as it’s important.

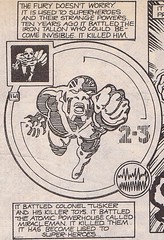

Moore’s early work on Captain Britain with Alan Davis provides another intriguing glimpse of his ideas about Marvelman. On the third page of the very first full episode he wrote, in Marvel Super-Heroes #387 (Marvel UK, July 1982), while describing the unstoppable Fury, an organic-machine hybrid created to kill superheroes, there is a caption that reads,

The Fury doesn’t worry. It is used to superheroes. Ten years ago it battled the Iron Tallon who could become invisible. It killed him.

It battled Colonel Tusker and his killer toys. It battled the atomic powerhouse called Miracleman. It killed them. It had become used to superheroes.

A month later, in Marvel Super-Heroes #388, Captain Britain finds himself in a graveyard, where there are gravestones for The Arachnid, Gaath, Colonel Tusker, Android Andy, Iron Tallon, Captain Roy Risk, Puppetman, and Miracleman. These are all analogues of old British comics characters The Spider, Garth, General Jumbo, Robot Archie, The Steel Claw, Colonel Dan Dare, Dolmann, and Marvelman, quite a number of whom would turn up many years later in Albion (WildStorm, 8/2005 – 11/2006), plotted by Moore and written by his daughter Leah and her husband, John Reppion.

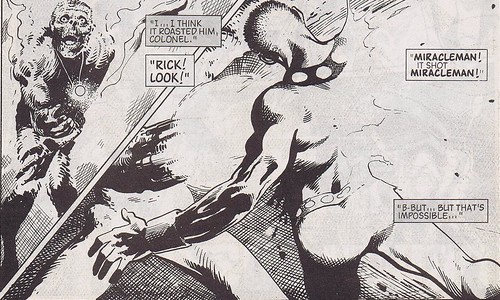

About a year later, in Daredevils #7 (July 1983) we see a woman called Linda McQuillan having a nightmare. She is actually Captain UK, a Captain Britain analogue from an alternate Earth, Earth-238 (as opposed to Captain Britain’s Earth-616), and it was on her Earth that all the superheroes got killed by The Fury. In her dream she is talking to her husband Rick, who turns out to be Young Miracleman, which can be seen by his uniform, and his being called Rick – as opposed to Young Marvelman, who was called Dick – and once again there is a list of superheroes that have been killed by the Fury: The Talon, Gaath, Android Andy, and the previously unmentioned Tom Rosetta, who had a magic stone that makes him invulnerable, like Tim Kelly from the old British Kelly’s Eye strip. And this time we get to see several of the characters who had previously only been referred to by name. In the last panel on the page the caption says,

Rick! Look! Miracleman! It shot Miracleman. B-But… but that’s impossible…

In the frame we see the back of the character referred to as Miracleman, wearing the uniform of Marvelman. It seems obvious that Moore had come up with a possible alternative name for Marvelman from very early on, as evidenced here and in the last part of his original Marvelman proposal to Dez Skinn.

To Be Continued…

(As ever, you can find larger versions of all the images in this post here.)

These are always a fascinating read. I’m really glad to hear you’re going to return to MiracleMan’s origin (sorry, I’ve been calling him Miracleman since the early 90s, MarvelMan sounds weird to me) being tied up with the Warpsmiths. I’ve heard quite a few times the biggest problem Marvel/Disney is having with reprinting the Moore stuff is they don’t want to buy or even license the Warpsmiths’ rights. That’s not to say figuring out the actual copyright holders is a small problem, but I’ve always wondered if the Warpsmiths’ rights story had any credibility or if it was just idle speculation.

This is a spellbounding article series, and this one shines especially for Padraig’s narration of himself crossing the threshold from amateur to professional fanboy.

And I think this is proof that it is not the character that drew folks in, but the work of the creators. So Marvel owning Moran now is entirely inconsequential. The clothes most assuredly do not make the man.

@Richard Caldwell – It’s not inconsequential if Marvel can get the Warrior/Eclipse series back into print and completed. That’s still a big “if” but an improvement on the situation that pertained from 1994-2009.

My understanding (and Padraig will almost certainly disabuse me of this over the coming weeks) is that the division of the MM rights in 1981/2 (and all subsequent re-divisions) relates to the overall property, but that the individual creators also own the specific rights to the work they did on the strip. If (big if) there is now a single solvent publisher that owns the overall MM property – and no other parties are contesting that – then that’s a kind of progress.

But there are other talented writers apart from Moore and Gaiman, and other artists beyond Leach, Davis, Veitch, Totleben and Buckingham – and I don’t see any reason why Marvel couldn’t make the character successful on their own terms if they wanted to. It’s not what anyone who’s currently interested in MM would like to see (myself included) but it’s not inconceivable either.

Fond memories of the Alchemists Head. A whole generation of SF and comics fans were nurtured by that oasis in the late 70s and early 80s.

@ Kate Halprin-

Kicking a dead horse is never creative, no matter what the cool kids say.

@ Richard – wise advice, and if only Alan Moore had followed it back in 1981 then neither of us would have heard of Marvelman, or Alan Moore.

It is very popular to dis on Moore these days, and while the bulk of his work is overvalued, there are still some works which garner the praise and more. There has got to be limits on the concepts of trying to redo or surpass certain icons from before. If Art maintains no standards then it loses all self-worth. Commercialism and its Capitalism parent are definitely bleeding whatever virtue from the world. Some stories are finite, and have been told enough. Otherwise, why not launch a MAUS sequel. I hear Chuck Austin isn’t doing anything.

Art is subjective, leave the Capitalism to the objectivists.

Uh, yes… I wasn’t aware that I was dissing Alan Moore by suggesting that other writers might possibly be able to write a character that a) he didn’t create, b) he doesn’t own, and c) he specifically handed over to another writer with his blessing/curse.

MM isn’t Maus, nor is it Before Watchmen. I have little or no interest in non-Moore/Gaiman MM stories (of which there are already hundreds) but the idea that only Moore (or Gaiman) could write for the character isn’t the shrieking affront to the natural order that you seem to imagine.

I was younger and Warrior was slightly older when I came across my first couple of issues, and it was V that hit with me first, before Marvelman; I’ve written about it here (http://suggestedformaturereaders.wordpress.com/2012/06/18/why-didnt-we-realise-what-they-were-doing-to-our-lives/) and it was pretty amateurish for the first few episodes until Kid Marvelman was vanquished. I do remember being blown away by the tabulating and questioning of his powers by Liz immediately after that, at just that hint of scientific process and realism.

And I’ve wondered about the Warpsmith tie-up, which Gaiman enthusiastically continued in his issues, notably Winter’s Tale. How would the Warpsmith material be included in any reprint? In terms of story it doesn’t need to be, but the significance of Aza Chorn’s eventual appearance is undermined without it…

Great pieces, great series. Personally I don’t think it’ll ever be republished. But it’s so easily available online that seems irrelevant. Shame we’ll never see the Gaiman-Buckingham story concluded, though.

This overwhelming sense of kismet has me inspired, mm will return, has returned, never left..thank you all for having such contagious enthusiasm for a property with such merit to our beloved medium, simple words can do no justice.

I was 14 years old when Warrior #1 came out. My father, who had read Marvelman as a boy, flicked through a copy in a local newsagents and of course had to buy it. We were both regular readers of DC and British Marvel reprints at the time. We had similar tastes in music and TV too, but it’s our conversations about Moore’s work in Warrior which stand out in my memory (along with the conventions where we got to meet Alan and co.).

Some of those Marvelman stories had wonderful cliffhangers and I remember discussing how on earth they would be resolved, and laughing while quoting lines from Bojeffries back and forth to each other. And who was V, anyway?

Moore’s work, especially in Warrior, had a profound and lasting effect on me too, Pádraig. When I revisit these stories now (the 26 issues are within reach as I type) they are still among my all-time favourite comics.

Actually, I think I can omit the word “among”.

I was recommended this website by means of my cousin. I am not sure whether this publish is written by means of him as nobody

else realize such specific approximately my trouble. You are wonderful!

Thanks!

Comments are closed.