Comic book enthusiasts know how educational the medium can be, but historically, educational institutions have been reticent at best to accept them as appropriate classroom material. Luckily for kids in the Five Boroughs, though, the New York City Department of Education sees things differently.

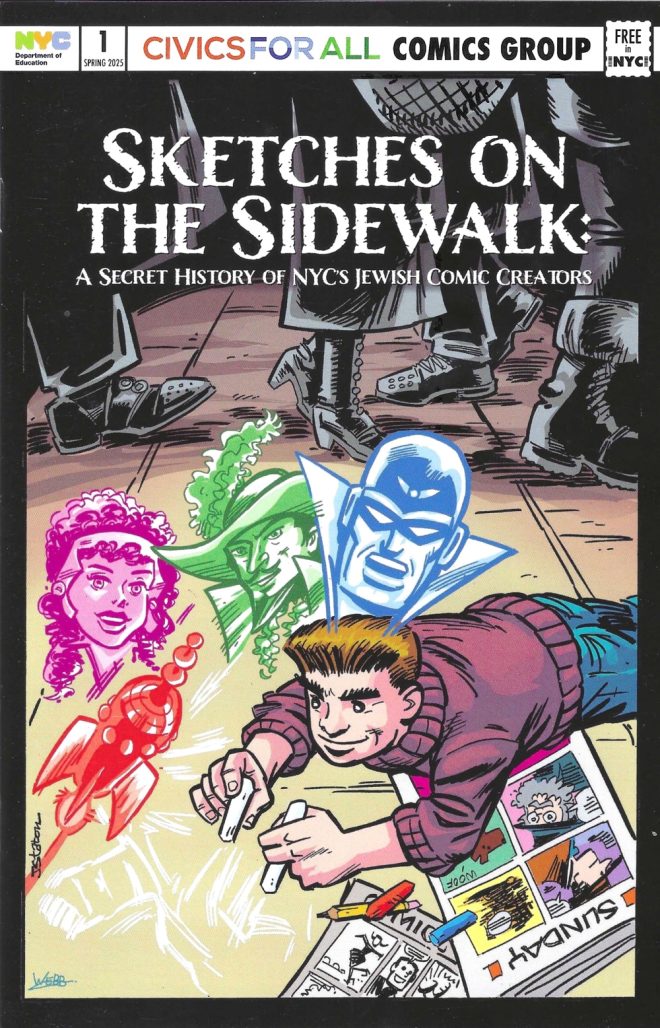

The Civics for All Comics Group has an innovative initiative to teach kids about social studies and history (especially NYC history) with a wide variety of comics about world-changing activists, political figures, and now, through the new Sketches on the Sidewalk series, the rich history of New York’s wealth of industry-defining comic book creators.

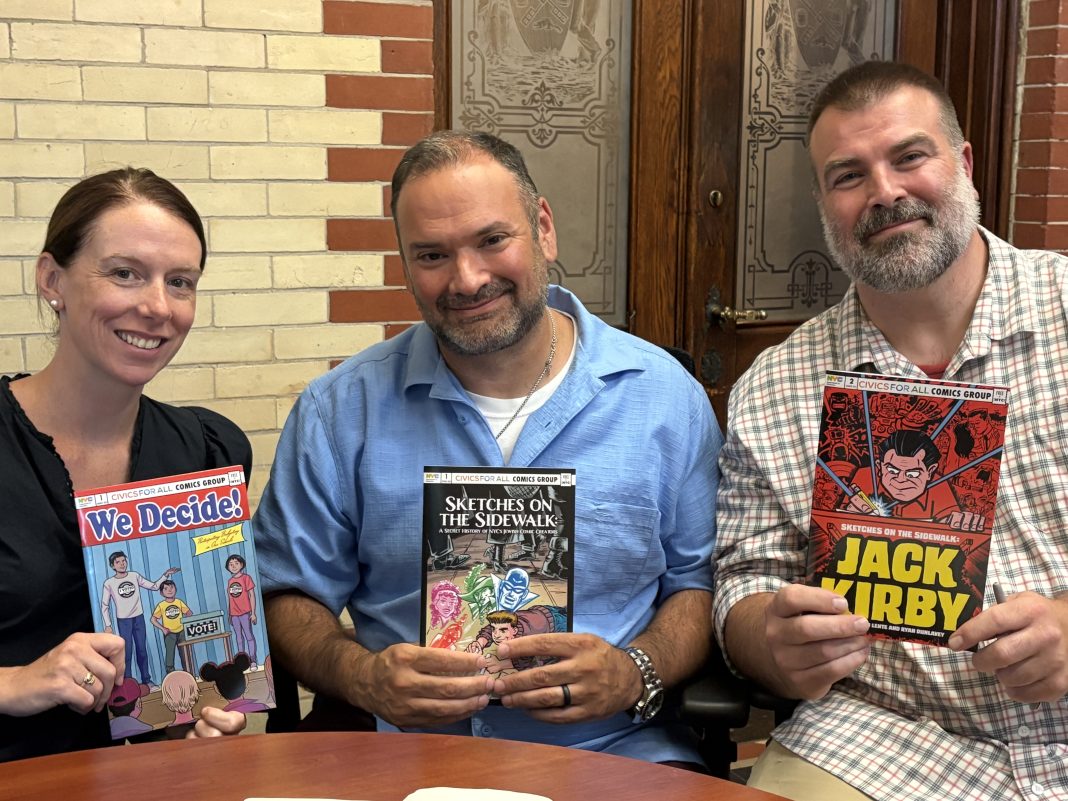

I had two great conversations with just a few of the people behind these ambitious comics. First, I visited the NYCDOE office to speak with Jenna Ryall, the director of Civics for All, Brian Carlin, the director of social studies, and Joe Schmidt, the senior instructional specialist.

Read along for more about this groundbreaking effort to make New York students more literate, socially conscious, and excited about comics!

Gregory Paul Silber: What makes comics uniquely suited to teach kids, particularly New York City Public School students, when it comes to social studies and civics?

Joe Schmidt: So there are kind of two answers to this, and then I’ll hand it off to Jenna to talk about the civics side of things. In some ways, I think it is about accessing youth culture. So students read comic books. They’re drawn to comic books. That doesn’t mean it’s unique to New York City; it’s unique to youth. So it is an opportunity for us to really think about things that are relevant to young people. But actually, to take it a step further, when you go to New York City and you think “what is the power of sequential visual narrative,” students are bombarded with images. Even if you just think about your trip here.

Silber: Oh, totally.

Schmidt: Any number of things, all of those tell some sort of story. So the power of teaching with comics is we get to tap in and teach the literacy of comics, teach the literacy of reading visual images and visual narrative. As well as being multimodal, not only are they images, they’re images with text. So it’s about accessing and then teaching students how to read this. So that’s one piece of it. I think the second piece of it is: comics allow for two kinds of empathy building. One is sort of what we think of as traditional empathy building, right? In seeing this, you are not only reading the words, you are imagining what’s going on in between the words and the pictures. You are really in some ways feeling what the characters are going through. Flip to the other side of empathy, which is historical empathy, that is different. With historical empathy, we want to think about what was going on at that particular time in the past. Comics allow for us to drop a student into thinking about what’s going on when Jack Kirby is drawing on the sidewalk in the 1930s in New York City. It’s much better to see that—I’m trying to flip quickly to the page—it’s much better to see that on the page than to just try to describe it just in prose.

Silber: Right.

Schmidt: So you actually teach historical empathy through the reading of comics. It is the text and images coming together to drop the student into that particular moment. I think those two speak to why comics in general are good for teaching anything, but also the past, and there’s also this aspect of teaching civics and civic education which I think Jenna is going to pick up on.

Jenna Ryall: Joe covered so much of it, to be honest, and I would agree that all those things apply to civics too. But also, there’s the reality that comics can be an entry point for what can be, for a lot of young people, kind of clunky content areas, and content areas that for a long time could sometimes be kind of just like, memorization, and you have to know the facts about this thing, and know the facts about that thing. So comics allow us to storify that in a way that can be an entry point for young people for these more complex historical topics or topics that are happening in the world right now. I think if you asked specifically New York City Public School students, obviously all of us in the room know there’s a unique history here, and a uniqueness to being New Yorkers, and our young people may not always be aware of that or embracing that. So we love for our young people to really think about how they fit into the New York story, and our comics in particular introduce them to lots of people that were part of that New York story, and I think they can see that recognized in stories that they can connect to. They’re building on empathy in that same way, and also thinking about civics. It’s so important for us that young people see themselves as members of their communities, and recognize how their communities are interdependent on each other. So many of these comics tell the stories through these characters. Obviously I’m thinking about these ones in particular, but I’m thinking about our Action Activists series for our younger students, and the way they’re using Squirrel and Pidgeon to get young people to think about their role in the community, and the way that they interact with each other, and the impact that they have on the people around them.

Silber: Sketches on the Sidewalk explores the rich history of New York City as a hub of comic book pioneers. What do you think is special about New York City that has made it home to so many important figures in the history of comics?

Brian Carlin: So I think that when you look at New York City history, I think New York City is U.S. history, right? It’s a microcosm. It’s everything from, if we talk about the different stories in American history, not just the creators who have been here, but the ground itself, the history that is unknown to many people, that some of these comic creators and comic stories, some of many comic book stories are set in New York. You go to the movies and see any of these movies based on comics, it’s amazing New York can survive all these things that happen. But I think part of the fact, whether it’s took stories of immigration, of conflict, of class, of power, of anything, whether it’s a civil war, whether it’s the Revolutionary War, whether it’s indigenous Americans, indigenous people, and the conflicts and the things that take place over time. I think that’s what shapes New York City’s history. And I think the people in New York, when they start telling stories and they start telling the stories that they’re a part of, and they’re able to channel those characters and put them in a place where they’re fighting oppression, or they’re fighting against a system that’s wrong or telling history that is unknown. We have so much history in New York City, but so little of it is known. And that’s why even besides these comics, a lot of our stories focus on people and events that people don’t know about, whether it’s the 1964 school boycott in segregation or the New York City draft riots, which is the largest riot in American history, which no one knows about. It took place right here in New York. So those are the kinds of stories we tell, and I think that people growing up in New York and part of the telling comic stories are part of that history.

Silber: So Sketches on the Sidewalk highlights the massive contributions of Jewish Americans in the history of comic books. I, too, am Jewish American. New York has long celebrated its diversity and has an especially storied Jewish community. Is there anything about Jewish culture, especially in New York City, that you think may have led to such an explosion of Jewish comics creators at the birth of the comic book industry in the 20th century?

Schmidt: I think we can look at this a couple of ways. One is a sort of historical answer and the other’s about “why were we doing this?” So we’re doing this as part of the Hidden Voices series. So if you look at the top of this, it’ll say, a “Hidden Voices comic.” This is actually part of a larger project. We’ve been working on the Hidden Voices Project, going back to 2018, a project that we start started with the Museum in the City of New York, focusing on New York City history, up through looking at LGBTQ history, up through looking at the history after the diaspora, up to looking now at Jewish Americans and Muslim Americans. Inside of these two comics, obviously, are connected to the Jewish Americans’ hidden voices. Oftentimes people talk about the fact that part of why we want to do these projects is to say, “This history is U.S. history,” right? This is not something separate. I don’t think you get much more to the fact of the matter than with these comics, right? Jewish American history is American history, and importantly, it is also New York City history, right?

Silber: Totally.

Schmidt: New York City is the largest population of Jewish people outside of Tel Aviv in the present day. Brian talked about this story of immigration. And so all of the folks who came here to New York City, who then ultimately, their sons and daughters are the ones who are contributing to this history of comics, right? And so we’re now pulling all these threads together to, like Jack Kirby is in the 1930s, drawing on the sidewalk outside of a tenement in the Lower East Side, right? Will Eisner will write the release of something that he calls Tenement Stories, [he] is growing up in different places in the Bronx and Brooklyn, but he is a New York City story. So why Jewish Americans? Partly because they end up in New York City. New York City is the home of comics. And so they are also the founders in many ways of the particular types of comics that we are lucky at when we’re talking about superhero comics, when, you know, they are the ones who are taking their experiences and then thinking about how do we humanize these characters, pulling them out of pulp magazines, and…create a Spider Man or Fantastic Four that have these human elements that they’re pulling on their own other autobiographies for. It’s just sort of all of these factors coming together in New York City, and then you have a bunch of different comics, but DC and Marvel are based here originally and that’s part of it as well.

Carlin: If you look at the history of the comics industry itself [it] wasn’t seen as a desirable profession. So who was able to deal with people that were being persecuted or didn’t have opportunities in other fields? So a lot of Jews elevated to that and an industry rose out of it. That was an opportunity. I think that’s part of the unique story.

Schmidt: And I mean, Paul (Levitz) really gets into that in Sketches on the Sidewalk #1, talking about kind of why and how.

Silber: Yeah, I mean, I read both of these issues and it was interesting, certainly in this first one, how he kind of synthesizes this huge… I mean, it’s incredible that he fits the stories of so many different creators into just like 20 pages.

Carlin: Yeah, that’s why we end up actually in the, you probably saw this in the comic, actually having at the back, sort of who’s who going through… you may have missed it on one page or panel where it mentions one figure, you can get a little bit more about them in the background.

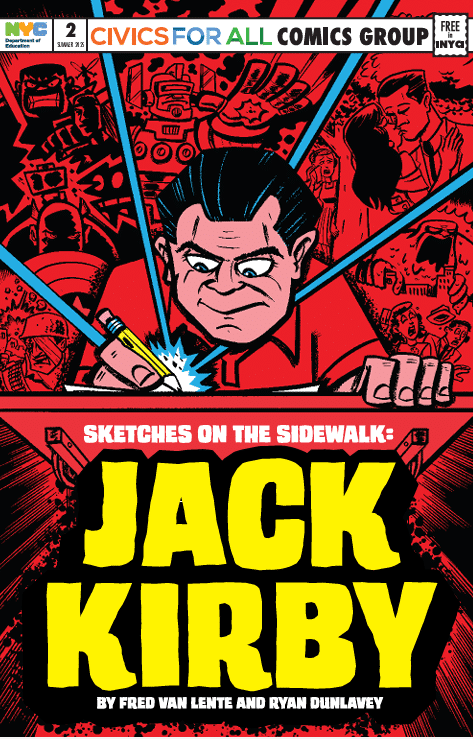

Silber: Sketches on the Sidewalk #2 is all about the beloved King of Comics, Jack Kirby. Why is it important to put this kind of spotlight on Kirby in particular?

Carlin: I think Kirby is an unsung hero. If you’re a fan of comics, you might know him. Even people who, like I mention, you, especially with Marvel and DC, just being so popular, Captain America being this ultimate symbol that people don’t realize that, you know, he’s one of the creators of Captain America, one of our most iconic superheroes. Other creators might have more attention than Jack Kirby, so the idea is that he is in one of our Hidden Voices profiles, and he tells a great story of… you know, he’s a New York City public school graduate. He fought in World War II. He brings these characters and stories to life that are still relevant today and telling you and the vast numbers of people he helped create. I think he’s worth that attention to get because so many of these characters people recognize, but have no idea who created it.

Schmidt: As you’re talking about this, one of the things that’s sort of interesting to me is, particularly for non comic fans, they may hear certain names. Those names are almost always the writers. And I think one of the things that this allows us to do is… comics, the art is so central, and so it also allows us to shine a light on one of the artists who really defines what particularly superhero comics looks like, you know, everything from the splash page to the particular kind of, universe building that he does, it allows us to say, like, this isn’t going to be done without the artist. And so, bring the artist into for the non-comic book people the conversation about comic book and comic book history.

Silber: Definitely. Yeah. I mean, you know, I ask the question because it’s important, but as a comic book enthusiast, for as huge as Kirby was, he’s still kind of a relatively unknown figure among the general populace.

Schmidt: I know, there’s a lot of reasons for this, but if we go outside and we ask someone about Stan Lee, most people who aren’t comic book people are [familiar with him)]. We ask about Jack Kirby to the people who are walking along, like, very few will. Different from if you’re walking into the Javits Center during Comic Con.

Ryall: I think what’s cool about it, though, is what can you kind of touch on a little bit too for our students… I think it’s important for us to give them examples of who might be an everyday New Yorker now. And that’s as someone who’s not a comic person. I had no idea who Jack was. They said we’re doing a comic about Jack Kirby. I was like, “Great. Tell me more about it, when it’s finished.” So the idea that to our young people, they are very familiar with the outcome, right? They know these characters. They know this work. But the story of Jack Kirby is a story that any of them could be living too. And so this idea that an average New Yorker making decisions that brought them to this place that now that they, as students all these years later, are surrounded by this person’s work and don’t know their name, I think that is a really interesting person who’s to be introduced to and also this concept of, you can create and you can produce something meaningful and it doesn’t mean everyone’s going to know your name. And it doesn’t mean that you have to have come from any different place than you’re coming from yourself. So for them to recognize, I think, a lot of their own story in Jack Kirby could be really great for the kids.

Silber: What do you hope kids take away from the Sketches on the Sidewalks series, especially the latest issue about Jack Kirby?

Carlin: I think the only thing I would [add], I think what’s great is when you dig into the stories and I think that’s what’s nice about the work Fred and I did on this, because it goes into a little bit different stories, whether it’s the X-Men or the Fantastic Four or any of these characters that he helped develop over time because like, he said before, it’s his influences growing up that make these characters and these stories so, so endearing. And even though he’s the artist, the way it was done, he was also heavily involved in the plotting and writing and development. He might not have been doing a script, but he’s developing those stories. So he’s part of the creation of the narratives that drive these stories too.

Schmidt: I think one of the takeaways is — one of the takeaways from all our comics — our hope is, yes, they get taught in the classroom, but also, that a kid comes across this and is like, “Oh, wait, what’s going on? It’s like Jack Kirby, what’s that [about]?” Visually it jumps out of you. And so we’re hoping that they just open it up and learn about this important person that oftentimes, you know, represents an unsung [figure]…

Silber: Plus, much like Kirby’s own art, it’s a very in-your-face cover, definitely grabs your attention. Of course, the latest issue is written and drawn by Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey respectively, who have chronicled comic book history in the Comic Book History of Comics, among other acclaimed projects, both as a team and individually. How do you go about selecting and recruiting creators for these comics?

Schmidt: So, you talked about being a fan of Fred and Ryan’s work from Action Philosophers. I think in a lot of ways, it came out of a couple of different things. It comes out of, we have attended, presented, and last year, we were able to table at Comic Con. And so it’s meeting people — and this goes back to, you know Fred and Ryan so we’re reaching out to them. And I think at the early Comic Con — not early Comic Con but an early one for us in 2015 or 2016 — and asking them to first come and talk about making comics with the teachers. So we did talks with them, and we talked about that, and then over time, we were thinking about under the Civics for All Initiative, creating the Civics for All comics group to teach both civic education and history education. And it was a natural fit to reach out to Fred and Ryan and ask them — at that point, they’d started the Action Presidents series. And so we said, “Any interest in doing Action Activists?” and that led to one of our first comics: Action Activists. The other is through the bringing in the March series and our Passport to Social Studies curriculum. We have a K-12 comprehensive curriculum, and as we were working on the eighth grade, Brian worked with the team that was drafting those lessons to bring them in. At that point, March book 2 was coming out, so we wanted to bring a section of March book 2 into the curriculum. And New York City was the first large district to introduce the March series into a curriculum, in this case, the Passport to Social Studies. And through that we got connected with Andrew Aydin. We had Congressman John Lewis come and speak to students and teachers a couple of different times. Actually one of his last public appearances was for students and teachers at the New York Historical Society in 2019. Yeah, so really special in very different ways, ways of meeting and working with folks. But it’s also sort of like, we reach out to people who are doing particular types of comics to say, hey, we’re working with Alex Segura on a number of comics. And we reached out to him because he worked on a comic for an NPR series on economics, and so we knew that might be a natural fit. He just worked with us, and we just published a book on participatory budgeting, which is part of the Civics for All Initiative. So it sort of becomes like, “Who makes sense? And does it work with what they’re doing?” Alex was like, “That would be great.” Fred and Ryan, obviously. And so we begin to think about it: Where do we go? Where would we like to go? What sorts of history, what other topics do we want to tell? And then we reach out to people who kind of match that.

Silber: Awesome. Do you guys want to add anything to that?

Carlin: Well, just that a lot of it is trying to tell the stories that either connect to our Hidden Voices work, so we find people who can be represented to tell their stories and who we can reach out to who could best fit. For example, Paul Levitz is local. He’s here. He ran DC for however many years…

Silber: Almost a decade, I think.

Carlin: He wrote for Marvel, DC, and is a legend in the industry. A lot of it’s been in the work that we’ve been doing and just reaching out and building relationships with artists and creators, and then building out their networks — like Greg Pak and other creators. And so we continue to look to also have authentic representation from people of the communities that are telling those stories, so they can be represented in those communities when we’re telling other people’s stories. And [we’re] just going to continue to do that. And we hear from the teachers and the students and how they’re excited about comics.

Schmidt: The last sort of thing I would tell you is in some ways, our comics work as a testament to the other work that we do, and the fact that we’ve been doing it for a very long time. So we started work on the Passport to Social Studies in 2014. Passport to Social Studies is the only New York City educator curriculum in all the core content areas. And because it is New York City educator-created, we know what is in it, we control what is in it, we also know oh, wait, there are things that we can bring in and make those connections. And then as we’re making those connections, we can think about who is the best fit to tell stories, whether it’s a connecting to the March series, the actual Passport to Social Studies curriculum, whether it’s building out the Civics for All curriculum, the Comics group, etc., as we’re thinking about what Civics For All is going to do. And then as we build on Hidden Voices to then say, okay, it all kind of comes together, and because it comes out of our team, we can continue to evolve, but also think about what are the best fits and what makes the most sense for our teachers and students.

Silber: Can you share anything about your plans for the future of the Sketches on the Sidewalk series? Or maybe just the Civics for All series in general?

Schmidt: Well, we have a few books in the words. One is Tenement Stories, working with the Lower East Side Tenement Museum to tell the story of a family, it’s one of the featured families that was a resident of the building there.

Carlin: Do you want to say who we’re doing that with?

Schmidt: Howard Chaykin and Paul Levitz.

Carlin: A luminary. Howard’s doing the art, and Paul is doing the script.

Schmidt: And similar to what we did in our Draft Riots comic, it’s based on research created and done by the Tenement Museum on the family and on the history of the building and the families that lived there.

Carlin: I mean, I will say my hope for the Sketches on the Sidewalk is to tell more of the stories of people who are connected to comics and other related fields. And also to think about the connections to the Hidden Voices project. So we have lots of different artists, both in the comics world and outside of the comics world, that appear in the future. And then in terms of things that we have already on the books that have not been published yet, we’re working on our comic on Mansa Musa, so thinking about global history connections. I think we can also speak about the comics that have not been sent to schools yet, but were just published.

Schmidt: Yeah, so Draft Riots is a comic that we published last year, but has not yet been distributed to schools. It’s Sketches on the Sidewalk, obviously. How to Be an Activist was a continuation of the How to Be an Action Activist series, but geared toward younger grades, and we will continue that. We’re working with Fred and Ryan on a comic on news literacy and the history of journalism. We will have an upcoming Action Activists #5, the Lucasa series, connected to the voice of the African diaspora. That is actually another project that we partnered with a cultural institution. In that case, it’s Historic Hudson Valley. They published this as a web toon, and we worked with them to make it into a floppy and then build a lot of fun back matter around that for students and for teachers to teach about the 1741 slave uprising in New York City. And We Decide is the comic that Alex Segura wrote that looks at participatory budgeting in New York City.

Silber: Before we wrap up, I do want to give you a chance to add anything that maybe I didn’t touch on that you’d like to talk about.

Carlin: We’re just excited to keep it going, so we just hope we can. We just printed our five millionth comic, and also, we’ve been in existence for five years, so we’re celebrating our fifth year anniversary. And for the last couple of years, we’ve been one of the top ten largest publishers of comics, based on numbers, in the country. I don’t know if you’ve ever looked at the statistics, but they are really interesting. Marvel and DC publish like 7-8 million a year, and then you’ve got IDW and a couple of others, and then there’s a whole group of people who are in the million to a million and a half [range]. So we’re in that million to a million a half of publishers.

Schmidt: I will also say, we don’t want to compare the different comics that we publish, but since we have not released them into schools, one way we can kind of look at their popularity is through kind of people who download them off of We Teach, which is the website where all of our materials are posted, and these are the two most popular comics that we have — just published in the last six months.

Carlin: Yeah, when Ryan hosted this on Bluesky, it was very popular. You know, it wasn’t a crazy viral post, but it was a popular post, I think that helped for sure.

Special thanks to Ross Finney for his help transcribing this interview.

Thanks for the interview. I’ve been curious about this project. But no link to the website for the free comics? https://sites.google.com/schools.nyc.gov/social-studies-and-civics/resources/comics-group

Comments are closed.