The Beat emailed Steve Cuzor to discuss his graphic novel adaptation of Stephen Crane’s classic Civil War novel, The Red Badge of Courage.

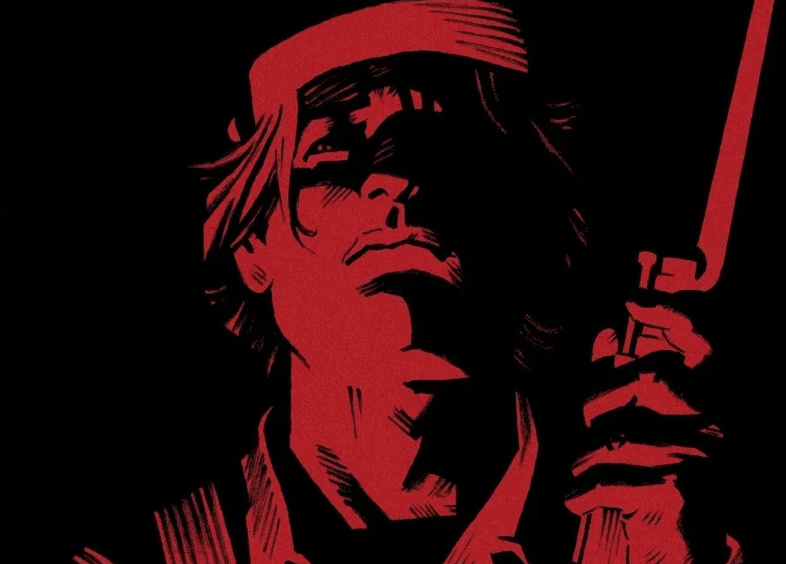

To be published by Abrams ComicArts on May 13, 2025, The Red Bad of Courage has already cemented its place in American literature. However, it comes alive with Cuzor’s illustrations in this new graphic novel adaptation. Cuzor not only pulls readers into the middle of the hectic and beautifully illustrated battles, but he also offers solemn and unflinching portraits of Civil War soldiers going on their day-to-day.

The Beat caught up with Cuzor to learn more about the project, who worked on it and what’s next for Cuzor.

This interview has been edited for content and length.

JAVIER PEREZ: Counting your previous works like Black Cotton Star and some of BlackJack taking place in Brooklyn in the late 20’s, what draws you to American stories?

STEVE CUZOR: When I was a child, there was a TV show on French television called La Dernière Séance, hosted by a French rock star who loved old movies — especially old Westerns. The show was filmed directly inside a movie theater — an old-style cinema from the 1950s. Every screening featured two films: one in color and the other in black and white, in the original version. Between the two, there was a Tex Avery cartoon. It aired once a month, and I never missed a single episode. I think that’s where my understanding of America — and especially Westerns — comes from.

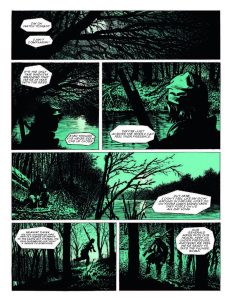

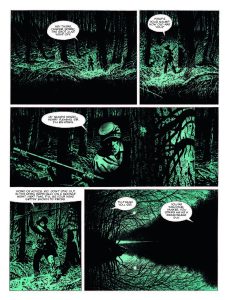

PEREZ: I love the prologue of the book, there seems to be a sense of impending doom from the start of the book. How important is that theme in the graphic novel and how did you go about showing that sense of dread from an artistic standpoint?

CUZOR: In the prologue, my goal was to show — without dialogue — all the main characters before the story actually begins. In those two pages, I also had to convey the sense of waiting, because the wait before a battle is when fear inevitably sets in for these young men. As it’s said in the story, “waiting is more painful than a bullet to the heart.” Henry is also afraid of not being the heroic soldier he imagined himself to be. He fears what others will think of him if he deserts.

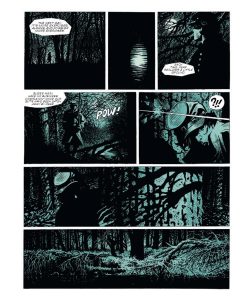

PEREZ: The graphic novel likes to keep the point of view of the protagonist, Henry Fleming. It doesn’t really give specific locations or times and that goes with how disorienting war can be. We can see Henry starts to lose his mind and the art follows that. Did you like working in those parameters?

CUZOR: I loved working with these elements because, for me, the pleasure doesn’t lie in drawing a character — my pleasure is in illustrating what a character feels. That requires a specific framing, a precise point of view, and a different lighting for each line of dialogue. What I illustrate is what the character says, not who they are. And when the character says nothing, then the image has to be filled with subtext.

PEREZ: It seems that a clear aim of Stephen Crane writing this work was a journalistic and honest account of war and I wonder how you took on that ethos in your art when you illustrated the book?

CUZOR: I only used what seemed important to me in the novel: Henry’s anxiety about not living up to the heroic soldier he had imagined himself to be. In the novel, the narrator is Stephen Crane. He talks about the characters in the third person. I felt that this technique had aged a little. So I created internal dialogues so that Henry could talk to himself. In addition to the battle raging outside, Henry is going through a real internal struggle. I kept that guiding thread throughout my graphic novel. For me, the important thing was not to betray Crane’s spirit.

The most challenging part, as an illustrator, was staging the battle scenes. Crane gives very little detail in his book about military tactics or how soldiers move in formation. Stephen Crane’s writing is so skillful that at times it reads like poetry — it evokes sensations in the reader but offers few concrete images. I had to create those images with a certain coherence, because that’s the very essence of a graphic novel.

PEREZ: I like the use of green and blue to show the difference between day and night. I think the cold stillness of the night sections really comes across in that color. What made you go with that choice?

CUZOR: It was a request I made to my wife, Meephe Versaevel, who does the coloring (we both work from home — it’s convenient). I told her, “For Red Badge, I don’t want color, I want light.” There were two reasons behind my request for monochrome: first, not to betray the black, white, and gray inking work with all its lighting effects; and second, because I didn’t want blue or gray uniforms that might make the reader wonder who’s winning or losing the battle — no green grass or blue skies, because war has only one color: the color of dust, smoke, and hell. The only time red appears in the book is on the cover… as a reminder of the title.

PEREZ: It seems that once Henry Fleming goes through a pretty dramatic experience he starts being reckless and that seems to be taken as courage by his fellow soldiers. Do you agree with the definition of courage?

CUZOR: Is it courage or a suicidal act? He’s angry with himself for not being the brave soldier he had imagined. He wants to redeem himself for the previous day, when he fled from the enemy. He doesn’t want to go through that inner torment again — he’d rather end it quickly, here and now. I have him move forward alone toward the enemy, alternating between gunfire and inner monologues. We know he’s lost his grip thanks to the reactions of the other soldiers left behind — “Where’s that idiot going?” — and who end up mocking him. Henry wanted revenge, and instead, he finds himself humiliated. In the end, it’s his officer who will restore his honor. Crane’s entire novel is built on these conflicting emotions.

PEREZ: How do you feel about graphic novels that cover historical events? And in a way, why comics? What does the comic medium bring to stories like these that can’t be done in movies or TV?

CUZOR: I’m not a specialist in historical books. What interests me when I create a graphic novel is human psychology — the human being and their struggle to find their place in the world and among others. In Black Cotton Star, which takes place during World War II, with Yves Sente as the writer, we told the story of the difficulties African Americans faced in being accepted into the U.S. Army. We didn’t tell the story of the war.

My next book will be about a bear hunt set in 1836 in the Great Lakes region, and about five characters who were never meant to meet. They will never catch the bear during this hunt, but they will be caught up by their own dark sides and their past. With the comic or graphic novel medium, you can tell every story in the world.

PEREZ: Lastly, is there anything you would like to add?

CUZOR: I’m proud to have brought my whole little family together for this graphic novel Red Badge of Courage — my wife Meephe for the colors and my son Tom for the chapter illustrations. This is the first time it has happened. Thank you.