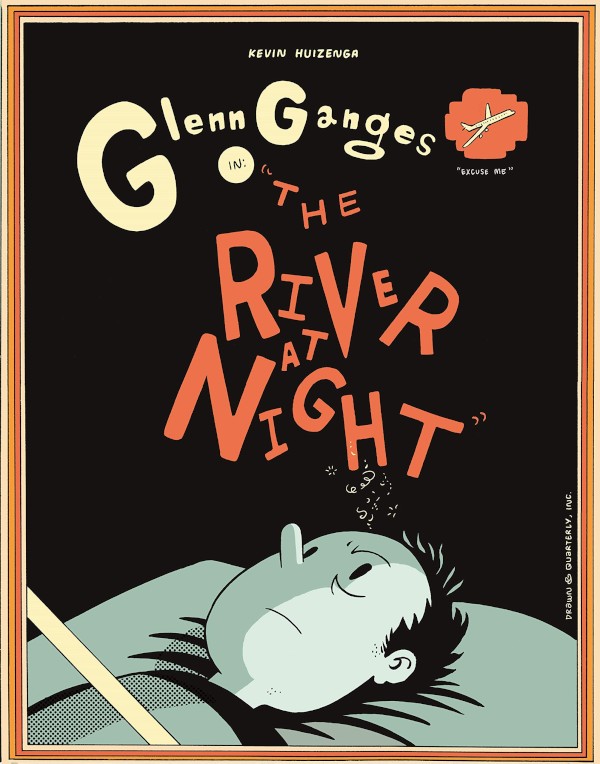

But no title better exudes the low-key psychological storytelling and fine-line formalist style than his series of 32-page magazine style comics, Ganges. Luckily, for those of us who have grown to love and cherish the stories of Glenn Ganges, whose insomnia and caffeine addiction keep him awake long enough to reflect on life, reading, his marriage, and the concept of time itself, Huizenga has once again graced us with Ganges stories in The River at Night published by Drawn and Quarterly.

A combination of stories told in previous Ganges issues and new material that fits like a puzzle piece into the abstract dive into consciousness that is Huizenga’s storytelling, The River at Night acts as a nod to long-time readers as well as a warm, fun welcome to newcomers.

I was fortunate enough to sit down and talk to Huizenga about how the book came about, how it feels to work on Glenn Ganges stories again, and how he handles balancing abstraction in reality.

Chloe Maveal: How does it feel combining your previous Ganges stories with some of the new material you’ve created for The River at Night?

Kevin Huizenga: Hm…How does it feel? It feels good. The book was sort of difficult to finish actually. Around the time I got to chapter four there was a break for a few years because I was going through a difficult time. Then I got distracted by other projects. So it feels good. Every once and a while I’m struck with some emotion about it but I do my best to go ahead tamp that down. [laughs]

Maveal: I’ve seen you in previous interviews really try to hammer in the fact that Glenn Ganges is not an autobiographical series. Since I refuse to be the thousandth person to ask you about that, I want to instead ask how you draw from your own experiences as a creator to create the slice-of-life moments we see with Glenn. What makes you put so much emphasis on those small moments in life that would normally go unnoticed?

Huizenga: It’s something I think I first learned from John Porcellino’s comics like King Cat. He’s talked about how he’s tried to do comic about the in-between moments or the in-between moments of life and that made a big impression on me. I’ve always been drawn to artwork that amplifies and mixes up the space around the everyday. Like anybody, my experience with the world is a busy, distracted speed. Then every once and a while there’s moments where everything opens up a little wider and things move more slowly. Things get more vivid. Those are the moments where things always connected in my head as the things that I wanted to write about and dwell upon. Those are the times that make me want to create art.

Maveal: Sort of playing on that. — and this is a broad question, I know — but why is The River at Night what it is? You tend to work in a continuum and cross over into your other series like Or Else or Curses where Glenn Ganges also shows up. So how did you go about choosing what did or didn’t make it in to this particular collection of Glenn stories?

Huizenga: When I started it was a series of 32 page comic books. I think around the time that I did the first issue I was starting to get interested in Little Lulu. And the way that comic works — and the way old Peanuts comics work as well — it seems like theres’s small stories that always seem to reset. It’s not like that’s unique to those comics; TV shows do that as well. But I had in my mind that I would keep the suburban version of Glenn as this stable world where I would write short stories and then let it reset. That was the thinking going in. But issue number one of Ganges, the series ended with Glenn in bed full of coffee, but I remember taking a walk around that time and it occurred to me that not only could I tell short stories and reset, but I could reset to Glenn awake in bed. It was amusing to me to think that the rest of my career I could just do that and be happy. From there I can tell stories about anything. I think that was the original idea and I planned to do that for a while and then, again, it’s just sort of evolved into something different.

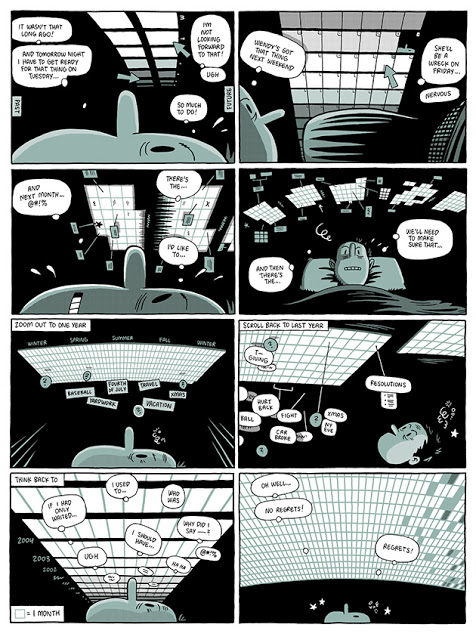

Maveal: You mention how time works a lot and you do so using a lot of formalist techniques. A lot of stories around The River at Night and Ganges are so abstract but relate so closely to what readers know the real world to be like. Do you ever have to restrain yourself from going to abstract when playing with themes like time and consciousness and things like that?

Huizenga: I think theres’a a section in chapter six where Glenn is walking around and seeing himself in mirrors and I know that was one of the weirder sections of the book. I did draw a few more pages that I cut out because it was just getting too weird. I mean, what I kept in was still pretty weird; but I’m always just trying to strike a balance. If I drift into too much weirdness I try to balance that out with good jokes and straight-forward storytelling. But if I do too much storytelling it feels like I’ve earned some space to mess around and be weird.

Maveal: There’s also a big mix of different influences. Your art definitely echoes a lot of old American newspaper comics. How did you decide that that was going to be the style you wanted to adopt when you began doing this?

Huizenga: Around the time that I made up Glenn in the first place, I was looking for a generic character. I had just read the Smithsonian collection of newspaper comics. I had been into comics for years before that but I never really had a sense of what idiom or style of comics I was most comfortable in. So when I first came across those Smithsonian strips where they were everyday domestic strips like Herman, Stumble Inn, or The Gumps and Barney Google. People often think that my style is a Tintin thing but I didn’t read [The Adventures of] TinTin until much later.

Maveal: To me it seems like there’s an emphasis on silence in a lot of the stories whether it’s the abstract page spreads where the focus is on varying shapes, or the nights where he’s staring off into nothing over the course of a few panels. You’ve also included a lot of speech bubbles where there’s no dialogue or narration. It comes across as being very focused on the visuals. Is that something you’ve done on purpose to let the art tell it’s own story?

Huizenga: That’s a really interesting question. I think when you’re talking about the empty word bubbles, often those are signifying breathing. I initially used those to signify the sound of Wendy — Glenn’s wife — asleep and breathing. I don’t know that I thought it through that thoroughly other than, at the time, that seemed like a good solution for getting across the idea of the sound of something soft like breathing. I guess I was also trying to make it seem strange in a way that would call more attention to it instead of adding a narration saying “Glenn could hear Wendy breathing”.

Maveal: It certainly makes it more interesting.

Huizenga: Yeah, and when I’m working with diagrams or abstraction, it’s an attempt to estrange things.

Maveal: The writing and visuals in your stories are so incredibly matched up. Do you have any rituals that go into making that synchronicity happen?

Huizenga: It’s nothing special but it is pretty much the same every time. I usually set out to write something and write down some notes of the basics of what I want to do. I have a template on 8.5 x 11 pieces of paper that have four rows of panels with little dividing lines for like, halfway, quarters, thirds, whatever. I print them out blank and I’ll just sit and start to translate the writing into page after page. The reason I do it on letter paper with a template is that there’s not much pressure. There’s structure to the page that I know I’m going to use, but also it’s disposable. If I do something and get frustrated I can just crinkle it up and toss it. But usually, it works really well once I start mapping things out. Then once I feel ready I’ll transfer that onto a bigger sheet of Bristol paper which becomes the final page. Then that gets scanned into the computer where all the tones get added.

Maveal: You do play with a lot of tones. So much of the book takes place at night so there’s so much shadowing and tonal play. Do you have to think a lot about how to make that dim lighting work for you?

Huizenga: Yeah, I do. I’ve always enjoyed being out at night and looking at the way the lights and shadows interact. I always ask myself why we don’t see this in movies and things like that, but then I realize that it’s very difficult to capture the darkness and light at night in the way our eyes see it. For the same reason it’s really difficult to take reference photos and use them. But I often thought that I’d like to do comics that take place outdoors, at night, and in a suburban neighborhood. If for no other reason than I’d like to capture the way it really looks. A lot of the time the case with comics is that the closer you try to make it look visually realistic, the farther you get from the simple comics storytelling that works best. So studying things with your eyes, doing really simple sketches, and doing the rest from memory is — I think — better than capturing everything exactly as it is in reality.

Huizenga: [laughs] Very attractive people, very wealthy people, successfully people, funny people, cool people —

Maveal: So as long as they’re cool and attractive and possibly wealthy then it’s fair game? [laughs]

Huizenga: Yeah, just not unpleasant people. I mean…they’re okay too, I guess. I don’t know. The ideal reader is definitely something that everyone thinks about. I honestly try not to calculate too much. I mean, as an artist you do have in your mind the person that is reading you closely and with good will and attention who will get your jokes, references, and be open to the vibe. But in most cases when I actually think about specific people reading my work I just feel embarassed or anxious. I try not to think about specific people.

Maveal: Is there anything you’d like to tell readers about what’s on the horizon for you creatively?

Huizenga: Oh man. I don’t know. Every day is a struggle to stabilize and clear out some free time that usually ends up giving way to daydreaming. Working on a new project gets harder and harder. There’s so many little things to take care of and to do that I’m just looking forward to a time when I can carve out a few hours a day to dive back into something big again. I did start a new series called Fielder, though. It’s like Ganges in that it’s a 32 page magazine-size comic book. In there you’ll see, more or less, all of my new stories. I’m also serializing another suburban Glen Ganges story in there. Hopefully #2 will be out some time next year.

The River at Night is available at all good comics retailers and through Drawn and Quarterly.