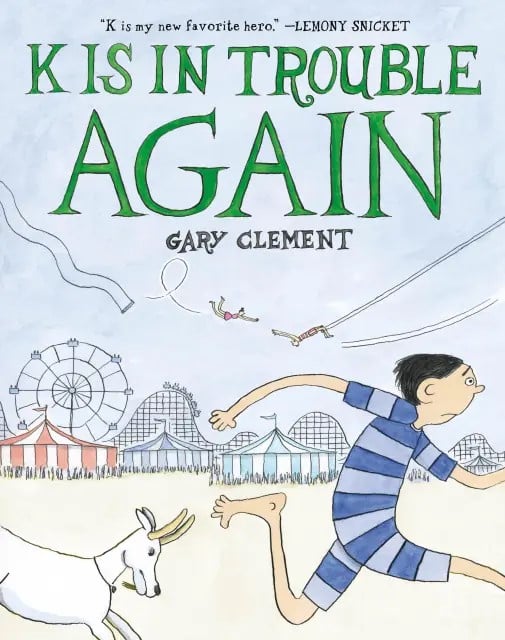

The Beat got a chance to catch up with Gary Clement and talk about K Is in Trouble Again, the creator’s most recent graphic novel, published by Little, Brown Ink. This is the second in this adorable and endearing series for young adults readers, though even regular adults might enjoy it, too.

Clement has written and illustrated many pictures books, among them, Swimming, Swimming, Just Stay Put, and The Great Poochini, for which he was awarded Canada’s prestigious Governor General’s Literary Award in Children’s Literature in 1999. His illustrations have appeared in the New York Times, Boston Globe and many other newspapers.

K Is in Trouble Again is Clement’s second OGN, following 2024’s K Is in Trouble about a small nervous child trying to figure out how to navigate the world around him.

Clement chatted with The Beat about the process of writing the K Is in Trouble series, Franz Kafka, anxiety, and trying to add a new word to the lexicon.

JAVIER PEREZ: Starting with K Is in Trouble Again, is it the second book in the series? Can you tell me about the first book?

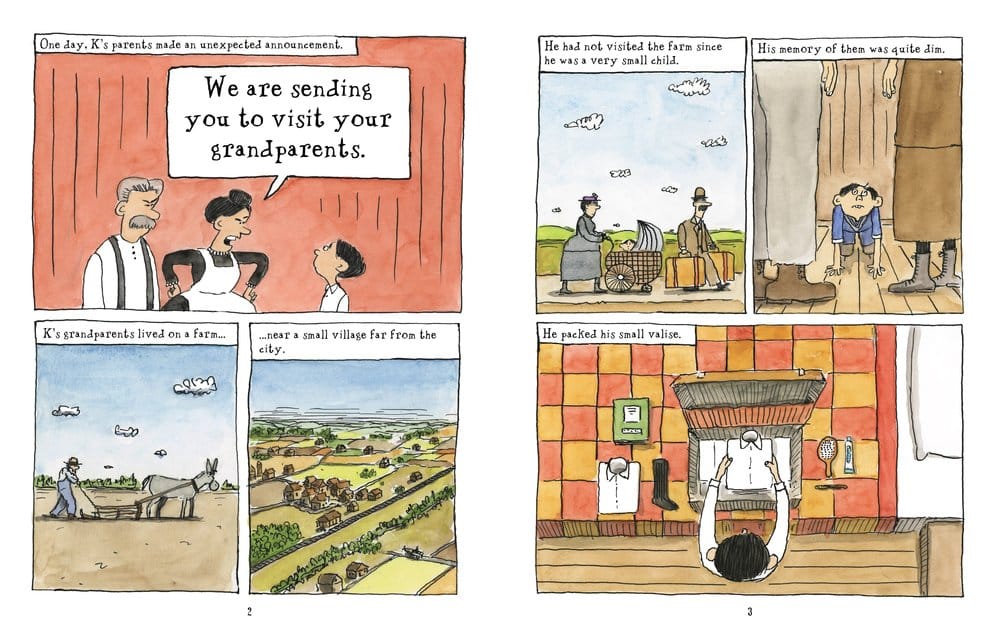

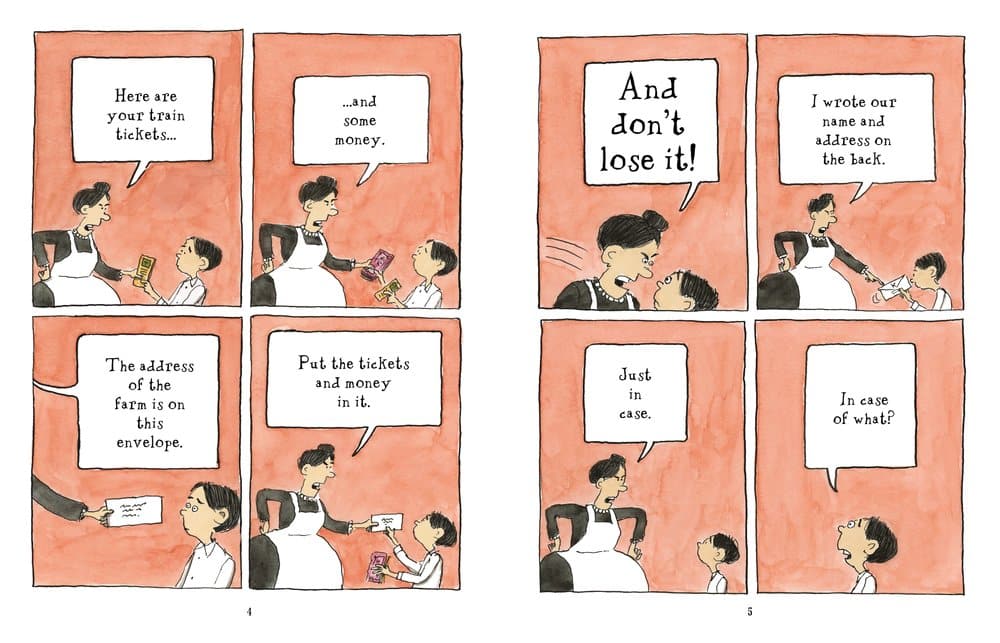

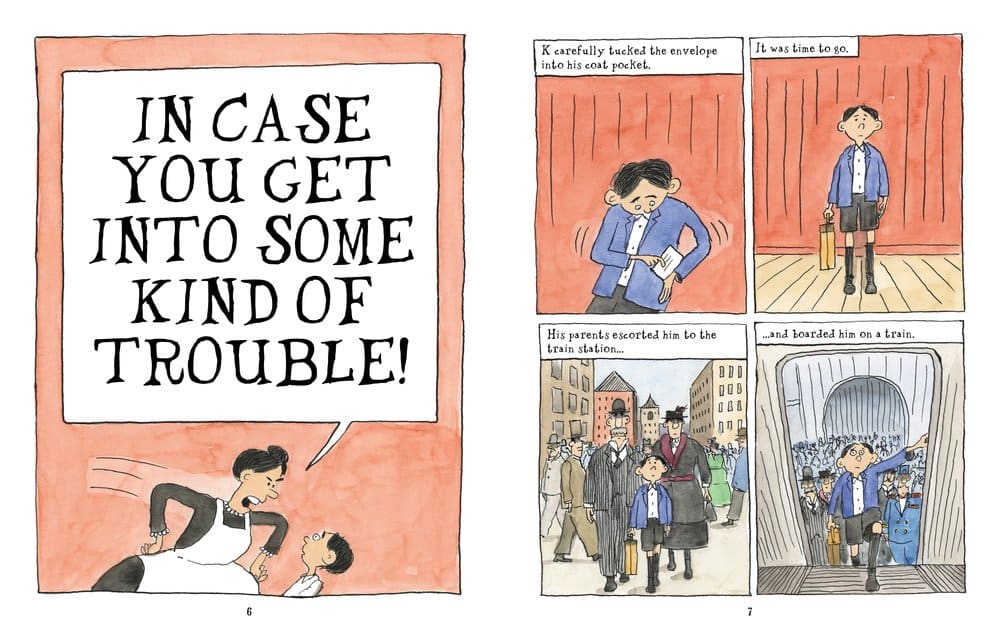

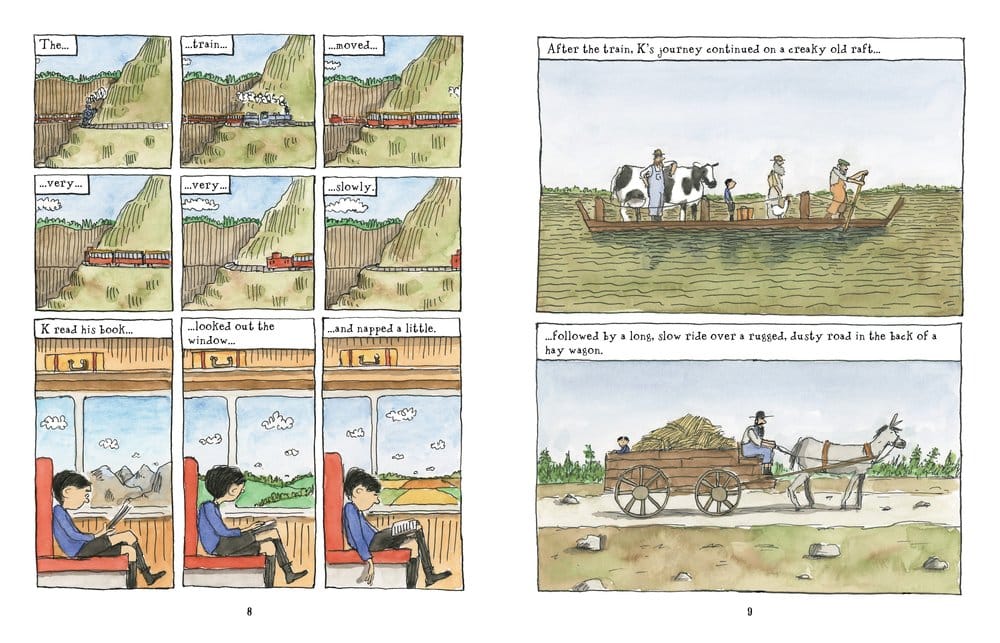

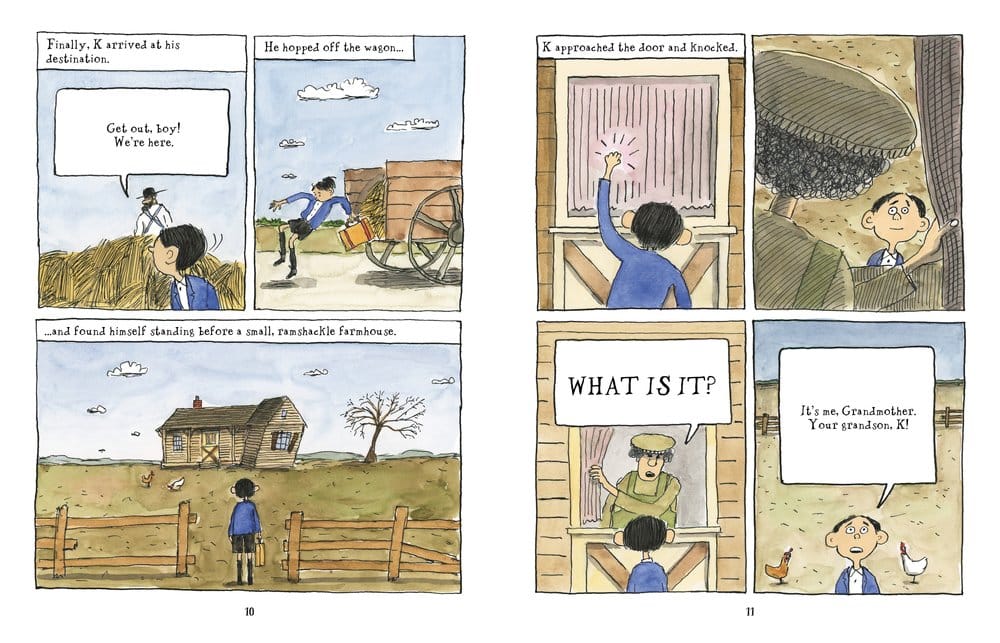

GARY CLEMENT: Well, the first book is appropriately called K Is in Trouble, instead of K Is in Trouble Again. Similarly, it is five stories about a boy named K who, despite every effort, always finds himself in trouble with some authority, either teachers, parents, station attendants, or school principals. He cannot stay out of trouble, and yet, even though this always happens to him, he is undaunted. He perseveres through hardship, and he continues to try to get through life.

The story is loosely based on a hybrid version of the life of Franz Kafka, my life as a child, and the stories of Kafka. So, I‘ve kind of woven actual details—and this is more in the first book than the second book—but there are details in the first book from Kafka’s actual biography, like the last story in the first book is about his father not letting him in from the balcony. Basically, he gets locked out of his apartment, and his father won’t let him in as a kind of punishment, which kind of happened to Kafka. His father didn’t put him on the balcony, but he put him out in the sort of entrance hall to the apartment that they lived in. They wouldn’t let him in as some sort of disciplinary action, and Kafka wrote about this in his letter to his father.

It’s this 80-page letter that he wrote, when he was an adult, like in his late 30s probably, and he outlines in the 80 pages a very long list of grievances that he has with his father, one of them being that episode in his childhood that traumatized him. Kafka never sent the letter. You know, he had this very terrible relationship with his father, whom he felt he could never live up to his father’s expectations. His father was quite disappointed with how Kafka turned out because his dad was this kind of robust, healthy, ex-military guy. Kafka was a, you know, sickly, frail, intellectual.

There are parts of the story from my biography. A lot of that has less to do with my parents, but more of it has to do with my horrible school experience as a child. I used my experiences and placed them on Kafka or vice versa to express a feeling like you’re not quite in the right place and are not really a part of what’s going on. K can’t form any friendships in his life; he has no friendships in school. The only friend he can make is with a beetle, which is drawn from the most famous Kafka story, Metamorphosis, in which he turns into a beetle.

So, I started this book as a straight-up biography of Kafka’s childhood. I thought I was going to do some graphic novel representation of what his childhood was like using biographical information. There’s enough of it to work with, but it morphed into what it became. I started thinking about what actual events in Kafka’s childhood made him, like what happened to him when he was a kid, that created that kind of worldview.

PEREZ: That mindset?

CLEMENT: Yeah, that mindset. It is so unique and idiosyncratic. There aren’t many authors who get their own words, you know? And with Kafka, we talk about things being Kafkaesque, sometimes used appropriately, sometimes not, but whatever. But it’s still a word, and there’s maybe a handful of authors in literary history who get their own word, you know, there’s Dickensian, but Kafka really cornered the market on a modern anxiety, and what is the condition of feeling isolated, and I think that there’s no one else like him, which is why he gets his own word.

PEREZ: I wanted to dig a little bit more into the balance between the autobiographical and the Kafka history, kind of when that melted together.

CLEMENT: OK, that was a moment when it melted together, and that came together when I got a very short residency at the Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont, which you’ve heard of, yes?

PEREZ: I have not. Can you tell me a little bit about it?

CLEMENT: I will tell you a little bit about it because it’s an amazing place. It’s like a cartoon university started by a graphic novelist named James Sturm, who wrote some fantastic books. Sturm, I guess, had a vision of having a place where you could really study the art of bookmaking, cartoon making, and graphic novel making. So, through picture books I’d done for kids, I applied for this residency through something called PJ Library. I got to go there to spend a week with James and nine or 10 other graphic novelists, and we were in a small town in Vermont called White River Junction, which is very close to Dartmouth University. We spent the week just working and then showing each other our work, and it was a great week. It was a turning point for me, in several ways, but that is when I wrote the first story of the first book, which is sort of when it came together. I can’t say what it was that did that, but I did think like, “How do I make the story relevant to me?” because I still think it’s got to be something meaningful to me.

The first story is about K going to school, being late, and being sent to the principal’s office. The headmistress and teachers of the school put him down, and the kids made fun of him.

The principal and teachers are literally based on experiences that I had in elementary school, whose name, even his name, is horrifying to me. It was Doctor Jacober, and he was a monster. He was this monstrous guy with a gigantic bald head and a short, kind of dumpy body, and he was just a mean SOB and terrorized me. So, I brought him into the story, and he became like the main antagonist. I weaved that with the Metamorphosis story; the focus is K and the beetle who saves his bacon and helps him escape the clutches of the principal and get out of school. They become friends, and he makes a deal with the beetle to make a story about the bug, which is the Kafka story part of it. They talk about what they want to do when they grow up, and he tells K, “Write a story about me.” Of course, he does, but much later in life. So that one story kind of weaves together all three elements that I was talking about, like Kafka’s biography, Kafka’s story, and my own biography. Although Kafka wasn’t a bad student, he did have this issue. If you read the letter to the father, this traumatized him, and from his point of view, in childhood, he had parents who weren’t attentive to him, which comes in the early part of the story.

PEREZ: Yeah, it’s very interesting because the concept of the story takes two exciting turns. One in that it turns autobiographical in the sense that you’re talking about your experiences, and the other in that it aims to be a children’s story that makes Kafka’s stories more approachable. I was wondering how you came about making that choice to be like, “Hey, these anxious stories are probably good for somebody young and would like to deal with that kind of anxiety?”

CLEMENT: Yeah, I firmly believe in having darker elements in children’s stories. I looked at people like William Steig and Tommy Unger, who wrote stories that have darkness in them, they have death and danger, and kids are in peril. And then there are guys like Lemony Snicket, who did a blurb for my first book, about kids constantly in turmoil and trouble, or being threatened by nefarious adults. So, I think there’s a place for that in children’s literature. I do. I think that I avoid anything with strong messages, especially positive ones. I’m just not one of those storytellers—nothing against them, I don’t do that. I wanted to write a book about my impression of growing up, and I think it’s universal enough.

You know, like there are going to be enough people out there who are going to be able to relate to that yes, But I think that the nature of childhood is basically you could look at kind of more Disney version of it as being a time of wonder or whatever, which you know, it is and can be. Still, it’s also a time of wondering, “What is going on here? I don’t understand how this world works,” because you’re just a kid, and people have rules that are hard to understand—like, “Why do I have to do that?” You have to because you’re a kid, and it can be disorienting and terrifying and could shape you, or I’m sure it does shape many people. I know it shaped me. So, I feel like it’s kind of an honest, approachable view of childhood. I think many people will be able to relate to it, and I think I told you the story about that book. A representative I met in Chicago who seemed like a very regular guy, seemed like a very athletic person, and just, I don’t know, seemed better adjusted than I was. I didn’t know him well. I just had met him, but he, you know, he reminded me of the coach from Friday Night Lights, not that I should judge people when they’re parents, and he pulled me aside and said, “You know, that book really resonated for me.” And I was like, “You? Like, really?” You don’t seem like that kind of guy, but anybody can be that kind of guy, or that kind of kid. I mean, it doesn’t have to be a guy, but, you know, that’s my experience. But yeah, I think that state of childhood is disorienting, and that’s kind of the world I was in. I was trying to. That was my worldview, the “Clement.” I’m going to work on that. I’m going to work on that.

PEREZ: We’ll throw it in there.

CLEMENT: Clements, you can see Clements.

PEREZ: Well, I wanted to pick up on that, but let me know if I’m off, in the sense that there doesn’t seem to be like stated names of characters.

CLEMENT: Right, and it was intentional because I think that, if they are the headmistress, the principal, or you just use letters, which I took from Kafka because, who, although he does occasionally use names in his stories, there are many people who have just titles—the station master, or whatever—so I thought that showed like a clear, divide between, like, his peers, his childishness and personality, and those people who are like the station master or the principal. They are kind of archetypes. Did you ever watch the old Charlie Brown animated TV stuff?

PEREZ: Like the Thanksgiving stuff?

CLEMENT: Yeah, there’s the Thanksgiving one, and bunch of stuff. You’d always hear the parents talking, but like, you would never hear their voice, or you would never hear their words. They’re unrelatable like, there is a kind of area where they can’t meet and kind of see eye to eye.

PEREZ: Yeah, it seems like not only are they unidentifiable, their perspective or what they think is important about the situation is completely off from the start yelling at him for something that seems very innocuous, but then him getting lost is just, “Oh well, you know. You’ve made your way back home. It’ll be fine.”

CLEMENT: It’s kind of like they don’t see him as he is like they refer to him as “Sir,” but certainly in the first book, there are characters that refer to him like they don’t really see who he is, but he sees them, and he tries to either avoid or somehow maneuver through the world around them but they don’t see him very clearly. They don’t really know what he is about, they’re not listening to him, you know, they’re not good listeners of the other characters. The only listener is the girl that he meets in the farm, whose name he doesn’t actually manage to get.

Perez: Which is something I wanted to ask, she doesn’t get his name and he doesn’t get a name either, but he wants to get her name, right?

CLEMENT: Towards the end he makes two shots at it, right? Before the farmer comes in to take the barrel, like, “Oh, I don’t even know your name. what’s your name?” He never asked anybody that. They never get to that point, but it’s too late because they’re coming and then he forgets at the end. So that’s important to him like all of a sudden he has someone. He doesn’t ask the beetles by name, but, you know, I think the assumption there is that the beetle maybe don’t have a name, and he gets enough other kinds of personal information. So yeah, that’s really important. And will he ever find out her name? Well, we don’t know. It’s possible.

PEREZ: Right I really took to the book and what really sticks to me is the idea of politeness & anxiety. I feel like at some point when I was young, somebody yelled at me instead of giving me a hug, and now my entire thing is I do not want to be in anybody’s way.

I need to be completely out of the way and I was thinking that’s a very universal theme, right? And it goes for both adults and young people, and I wanted to pick your brain at that, if you felt that way growing up or what made you want to give that kind of story, which I think is very powerful. Again like you said, a guy that was a buff guy to like a little kid who might not be sure what he’s doing.

So it was the difference between being polite and being anxious, I feel like there’s situations in my life where I just need to get this done, so I’m out of the way of people and somebody would look at me like, why are you being so nervous about this thing?

CLEMENT: Yeah, I mean first of all you said some adults feel that way too. I think adults feel that way l because of how they felt as kids, there’s a direct line, it’s linear, you know? Or the things that you learned as a kid, and unless you make a conscious effort to deal with them, you carry them, you drag them with you into your adult life and I think there’s this idea, K is very polite, he avoids people but that’s not gonna cut it. For him in terms of making his way through the world because he’s dealing with people who are just not open to him in any way. So being polite or not being polite is not a strategy, that’s gonna work.

Which I guess creates anxiety because you think, “How am I gonna make it through this? how am I gonna survive this day or this, this moment?” It’s not easy; it’s gonna be hard. You can’t just kind of batten down the hatches and wait till the storm is over, you have an opportunity to escape and maybe you never do. But the anxiety thing, yeah it’s tough, you just carry it with you and I do think it starts early. I think that we do learn those things and one never fully gets cured of anxiety or whether you just really learn how to manage it. I mean, this idea of anxiety, because K leads a very anxious life, he never knows what’s around the corner but generally this was also a decision that I made and was kind of really supported by my editor.

Like something else always happens. There’s always another beat, there’s like some other complication that K did not foresee, because you never know what’s gonna happen from moment to moment And so he doesn’t ever have that luxury of being able to take a breather and just say, “All right, that’s over with,” because it’s never over, because there’s always something else coming around the corner, an example, I think, would be in the train when he’s escaping the farm and getting finally getting back to the city, and he thinks like he’s clear And then the goat’s there, like, you know, like this was, that was supposed to be his escape, like that would have been the end of the story, except that it’s not, you know, there’s There is another complication, another beat.

PEREZ: I wanted to ask about how that conversation with your editor went. Was it like, “Hey, you need to have a happy ending here,” or?

CLEMENT: No, absolutely. She, she’s completely against happy endings, which is why we get along so well, I had one of the stories, and it had kind of a reasonably, like I wouldn’t call it like a fairy tale ending, but it was sort of a resolved ending maybe, a neutral conclusion and my editor was like “no, you can’t do that. That doesn’t belong in this universe” And she was right. so I changed that but it was definitely when I thought about it for a second. I thought, yeah of course, that doesn’t make any sense whatsoever. It doesn’t belong here, you know, this is not the world. This is a world where he lives and he’ll continue to be clothed and fed and stuff like that. K is not in mortal danger, but it’s never a happy ending. It can’t ever be a happy ending. It could just be an ending, you know, and then he goes to sleep and then there’s the next day, and, and we’re more terrible crap will happen, yeah.

PEREZ: Lastly and I wanted to ask you why a book like K is Trouble Again is a good book for our hectic and stressful times

CLEMENT: I think that it’s possible to read K and K stories and feel like you’re not the only person, you know, suffering from anxiety or worried about being tormented by the world that you live in and I think knowing that could make you feel a little bit better. Just knowing that, well, what do they say, misery loves company, right? so maybe knowing that everyone’s miserable, and we can all kind of relate to. Dealing with the daily kind of mundane terror, this is something we can all relate to each other, a level we can all relate to on that’s a way to feel better.

PEREZ: And you think that’s a good message for kids? Do you think they will get it?

CLEMENT: We’ll find out, I guess. I think kids can relate to the book. I think kids and adults can read it. And well, not every kid’s gonna feel that way, but I think, it’s a quirky book for sure, and there’s a darkness in it but there’s also humor, and I think that’s relatable enough. Somewhere down the line, everyone’s had a terrible teacher or a terrible incident at school, or a fight with their parents, or something that seemed that seems completely inexplicable, and you don’t understand how that happened: “Why is my world so terrible?” Is there a kid out there who has not felt that at some point? I don’t know. I doubt it. I think at that level, it’s for every kid and every kid should read it right now. Or buy it and read it and you know, and if you don’t agree with it, get back to me. Buy two copies, let somebody else know, check it out as a gift!

Check out K is in Trouble Again out on by Little, Brown Ink here or your local comic store!

Editorial note: In the original interview there was a mistake, the wrong publisher was credited. The correct publisher is Little, Brown Ink.

My apologies.