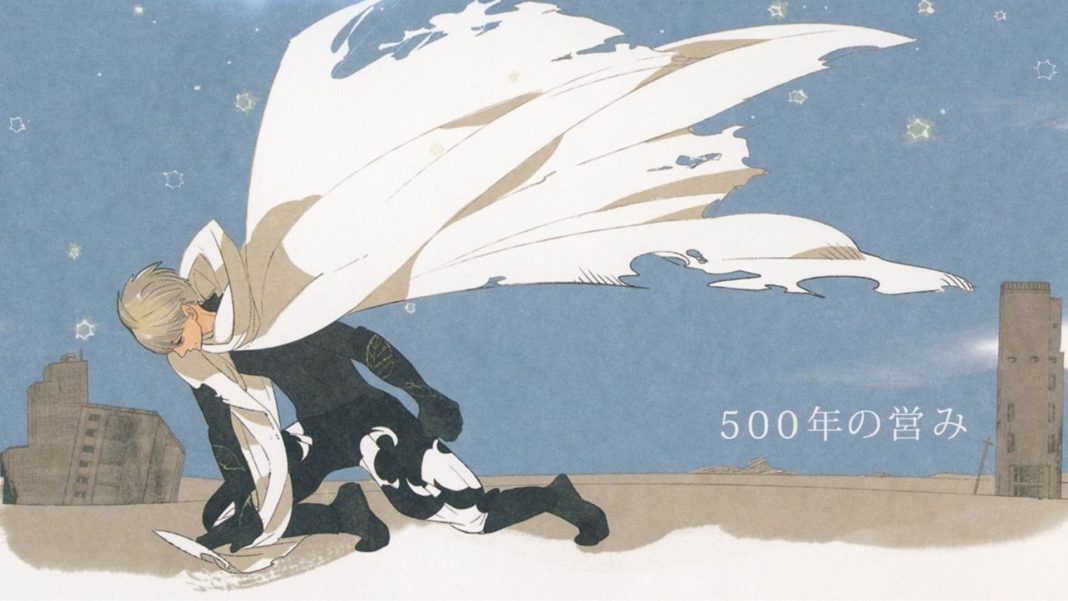

2025 marks His Romance of 500 Years‘ 15th year since its serialization. This Boys Love manga is from exceptional creator Hiko Yamanaka, who’s an all-rounder. From sci-fi Boys Love manga such as His Romance of 500 Years and Ikigami & Donor to the gender-bender shojo series with queer elements The Prince in His Dark Days, you can count on Yamanaka to always surprise and compel you in the best possible way. I wasn’t the least bit surprised to see His Romance of 500 Years discussed in a conference I attended on Human-Robot interaction in Boys Love/Girls Love manga a couple of years back.

Recently revisiting this single-volume series made me once again realize how, despite being a 15-year-old story, it’s as fresh, evocative and relatable as ever. It also brought back certain questions and topics I’ve found myself going back to that I decided to discuss through this comic.

Human, Nature

It was during the early days of the pandemic and we were under strict lockdown when I started to give more serious thought about the ways we communicate, and communication in general. It was curious how people were attributing human emotions or actions to nature, how nature was “taking revenge” or animals “taking back their spaces” simply because animals like deer started appearing in now empty city streets. The reasons behind applying this human perspective to the ways nature acts are beyond the scope of this post, but what it underlines is of interest to me.

What nature does is simply restore a balance. The missing piece in the thought process above is that there’s actually a boundary constantly controlled and kept between city life and natural habitat. There is invisible but constant intervention: pest control, pruning, repairing, trash collection, cleaning, noise and air pollution from our simply existing on the streets. When you remove all that from the living spaces, it’s natural for animals to appear after a while.

It’s curious how we forget that we exist, by ourselves and in relation to our community, and as an extension, in relation to the world. We forget that we take space, we consume and we pollute, we leave a footprint and not in ways we probably can imagine. We also forget how human we are, both in the way we are, how we relate and communicate. That we aren’t some omnipotent, omniscient being. Fiction often deals with the fear of humans not being at the top of the food chain, and for good reasons.

What I mean by our communication being human, for example, can be seen in the way we talk to pets we share our homes with. The only way we know how to reason is by using words: pleading, warning, assigning cute names and sweet-talking them. Or when we look at a dog panting, we assume it’s happy and smiling simply because the corners of its mouth are curved upwards.

And it begs the question. Why can’t non-human beings and natural resources have an innate worth of themselves? Why, for humans to protect them, do they have to see them as “humans”? This presents itself in naming animals that belong to an endangered species. Only by seeing them as “one of us” and assigning a personality, do we care about them.

Only Human

But the way we communicate and relate is only human. Leaving the complexity discussion aside, we can’t communicate the way a dolphin or a cockroach does. Unless they are taught through repetition, just like how we learn a foreign language, cats or dogs can’t understand words and respond to us accordingly via movement or sound.

I found myself revisiting these exact thoughts when generative AI and ChatGPT became available to the general public’s use, but of course, the research of artificial intelligence dates back to the 1950s.

When one doesn’t know the very basics of how AI or even a computer works, and presses a button and gets an image, a text or a melody in return, one can’t help but assign “creativity” to a machine. This is because the human behind these creations is invisible. Similar to how electronic music or digital illustrations weren’t seen as legitimate art because people valued the physical capabilities of a trained hand over the creativity behind composing or performing a song, we now view AI as we did a computer back then.

Considering we are still behind on comprehending the importance of intellectual property, and not everything that creators, journalists and academics put online is “free real estate“, AI making the data it’s trained on invisible, and presenting itself as a “machine doing it” makes it impossible to truly discuss the implications of releasing such technology without proper legal and ethical groundwork. When it is, actually, nothing but a giant meat grinder.

Robo Sapiens

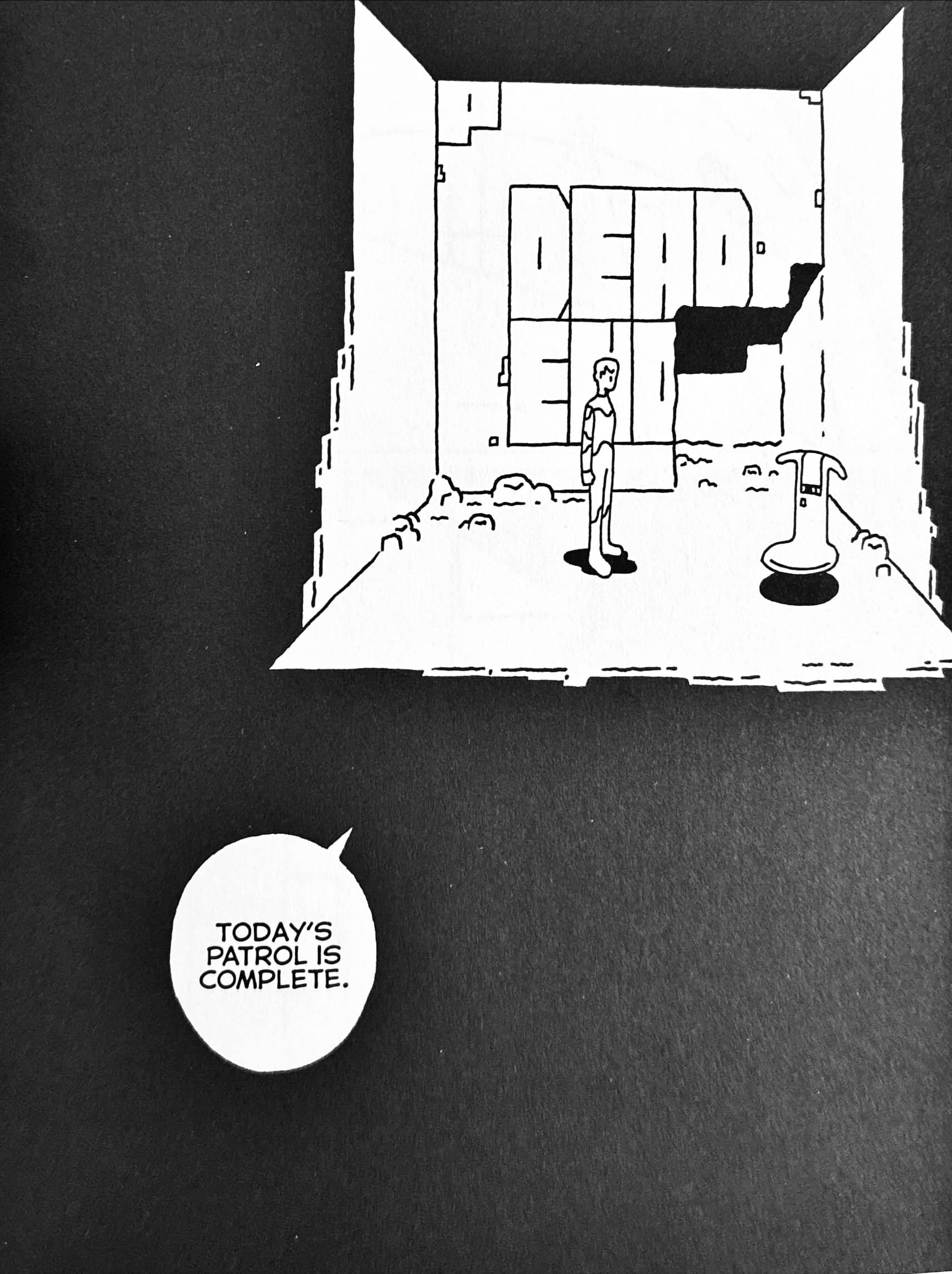

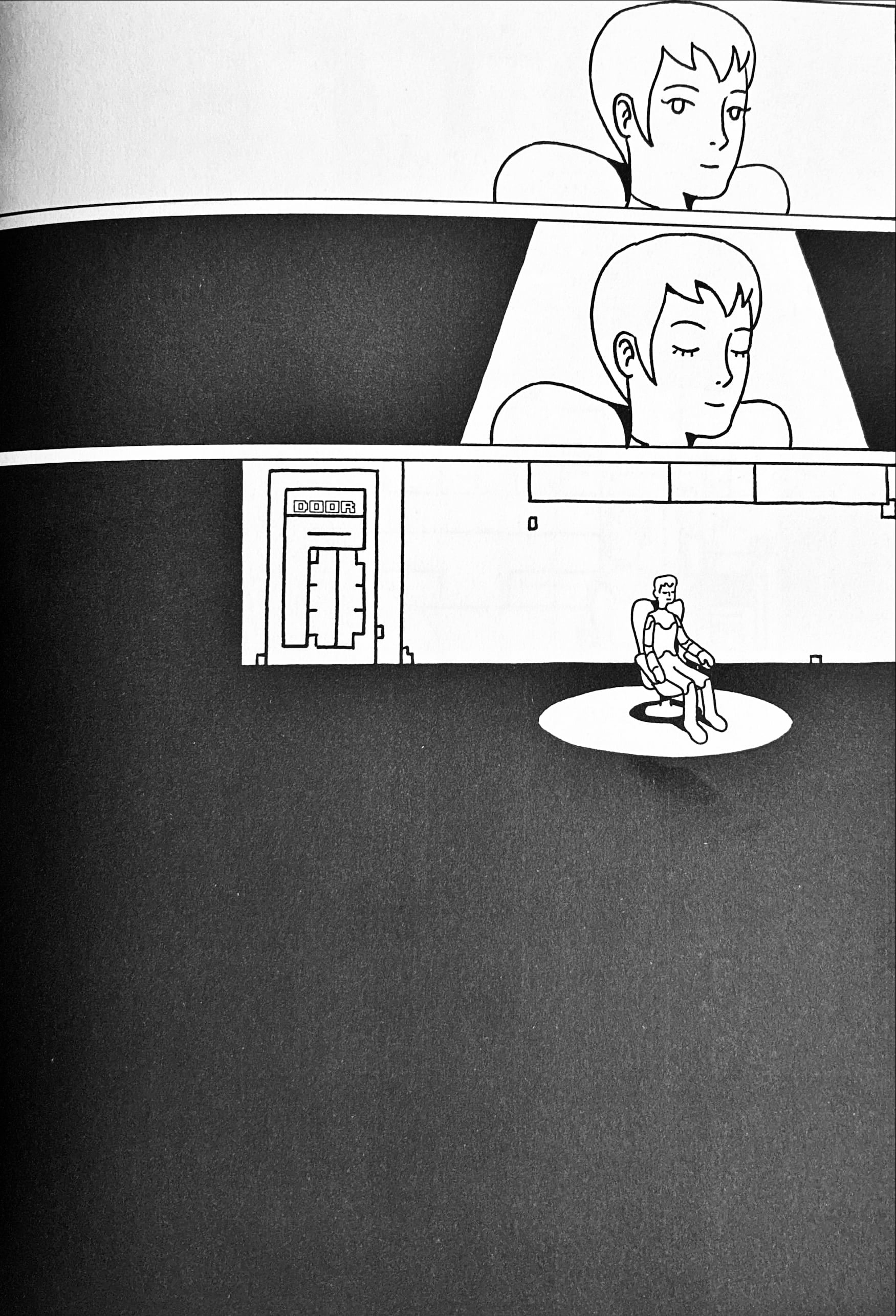

All that said, I believe this awareness doesn’t exempt us from feeling human emotions for machines. Consider chapter 7 in Robo Sapiens: Tales of Tomorrow by Toranosuke Shimada, where a humanoid robot is tasked to patrol storages and radiation levels. At first, humans visit this robot weekly, then monthly, then annually. They gradually stop interacting with the robot but just stop by, collect the data, and leave while the robot smiles and waves at them behind their backs.

After a century, they stop visiting altogether and there’s a panel where the robot sits under an over-the-head lighting, all alone, the rest of the room in darkness. Even when the reader understands that unless you program the robot to stop patrolling, it’ll continue to patrol forever, it’s still a devastating panel. You can’t help but feel empathetic to the robotic worker. It evokes a sense of abandonment.

His Romance of 500 Years

Our comprehension of AI as a “machine that creates” and the humanness of this projection on our part is of interest to me and the reason why I felt the pull to read His Romance of 500 Years again. Here’s the premise of the story for the uninitiated.

Ota and Yamada families have bad blood between them, and the hostility lives on with the current sons Hikaru Ota and Torao Yamada. What changes the dynamic is that Torao falls for Hikaru, and when they meet by chance in college at a gay bar, it turns out the feeling’s mutual. Hikaru likening their relationship to Romeo and Juliet is almost like an ominous premonition because Hikaru ends up dying while trying to save someone.

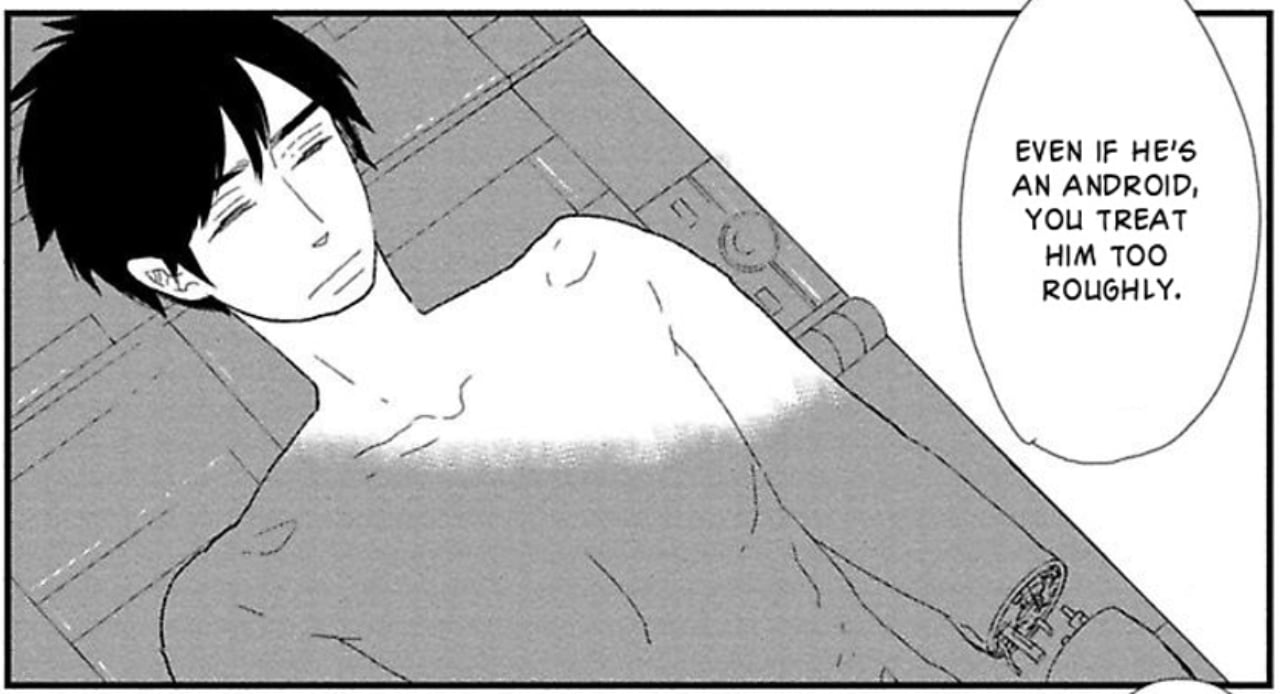

The life they built together all these years unexpectedly collapses and crushes Torao under its weight. He tries to die by suicide and doesn’t die, but is cryogenically frozen until medicine is advanced enough to treat the young man. His family also decides to create an android in the likeness of Hikaru, including memories, habits and all, to be present when Torao wakes up. He does wake up after 250 years, and the android Hikaru is there for Torao to activate him. But the android that’s supposed to be a perfect copy of Hikaru, is lacking by 30%. Torao’s estimation, not mine.

Even with his family’s good intentions, Torao rejects Hikaru B because, despite looking and sounding very similar to him, he is different than Hikaru in the slightest of details, and those seemingly insignificant details are what makes Hikaru, Hikaru. The time has marched on mercilessly during the time he was frozen, but to him, he blinked and now he’s here. On top of that, he’s expected to keep being in love with this less-than-ideal, machine-smelling, whirring, uncanny version of his perfect, beloved partner he sacrificed so much to be with.

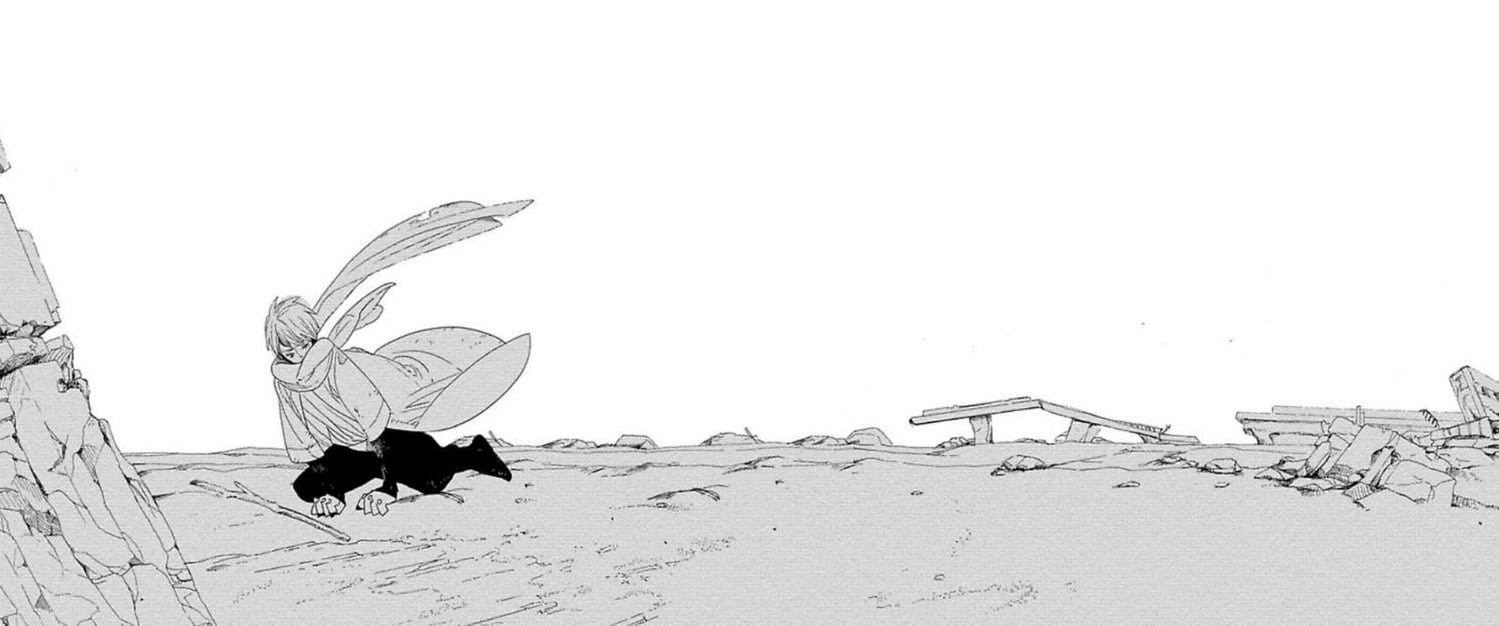

Interestingly, Torao eventually falls in love with Hikaru B. Even when he’s presented the perfected copy Hikaru A, and B is discarded, then lost in the desert after protecting Torao, Torao searches for Hikaru B for the following 250 years. Hence the 500-year-long love.

But Hikaru B is this version of Hikaru that’s frozen in time, stuck forever. Unless you program him differently or feed him new data, he’ll serve Torao until the day he breaks down.

Perfect Imperfection

Human Hikaru is perfect in his human imperfection. He’s in the flesh, he’s the one with who Torao built a life together. We could raise the question of whether there’s any significant difference between the two circumstances in the end, but unlike Hikaru B, he wasn’t a culmination of data about Torao, uploaded in mere seconds to mimic a lover. In this sense, Hikaru B is an imperfect copy of an imperfectly perfect Hikaru. Coupled with his “android-ness” seeping into his speech, Hikaru B feels like an insult to everything Torao holds dear. Especially since the android was the doing of his family who rejected him for being gay and falling for the “Ota guy”.

Now that Torao has awakened this annoying android programmed for heavy duty with the body of a houseworker, they have to coexist together because Torao has been detached from the ever-changing world and needs Hikaru B’s help. The time they spend together is constantly paralleled with the time he has spent with the human Hikaru, underlining all the ways Hikaru B is almost identical to his blueprint, but not quite.

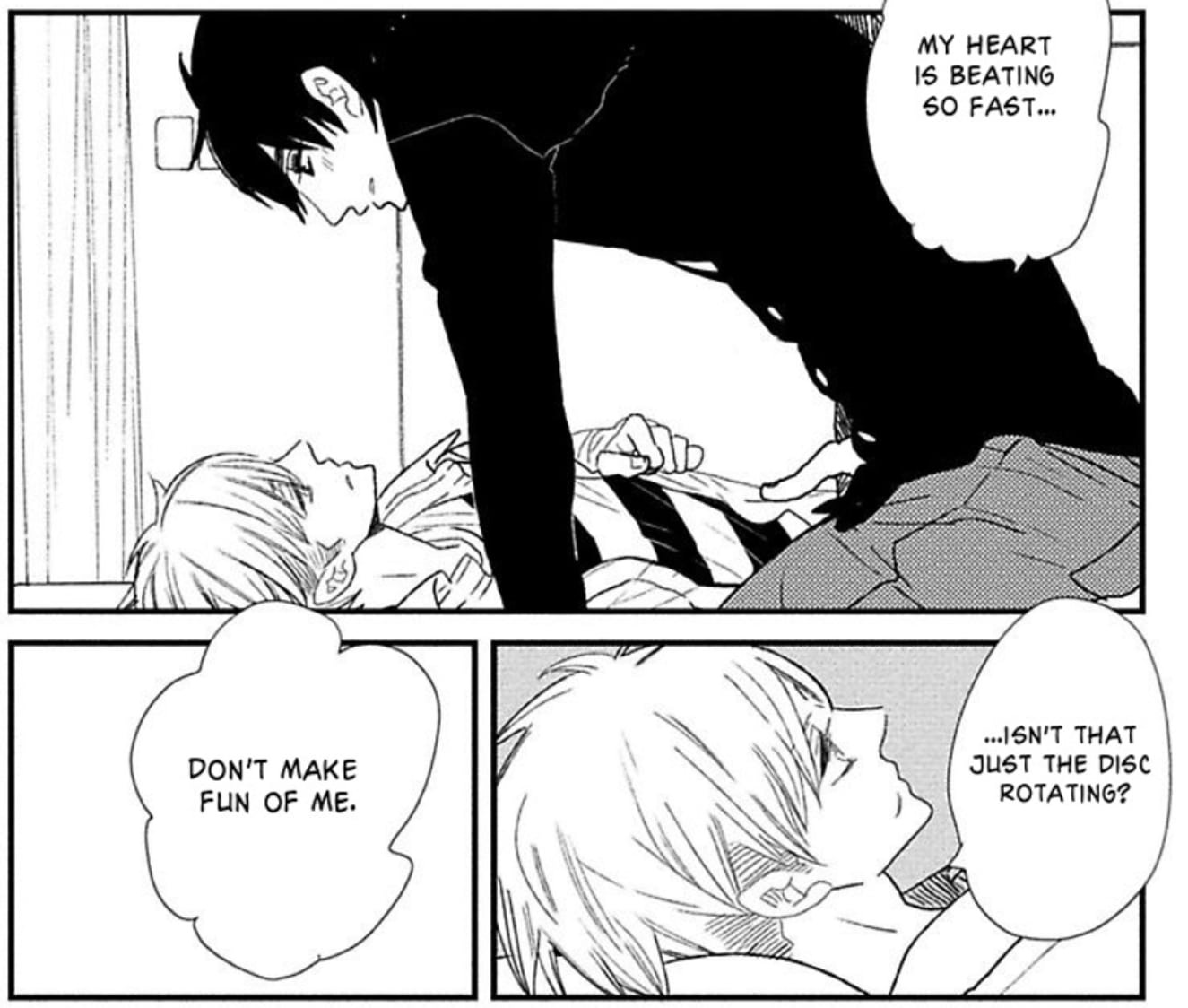

The educational videos Torao is required to finish to acclimate himself to the new world, stress that only through acknowledging that androids aren’t human, can androids and humans safely coexist. In the beginning, Torao incessantly refuses Hikaru B’s hand, but he’s only human after all. How can he not feel the warmth of a companion who tries to get better at peeling apples for his sake? How can he not find sympathy and acceptance, eerily the same way as human Hikaru did in the past, in embracing this prickly character of his? After a while, despite the whirring, the mechanical smell, the incompetence, Torao can’t help but inevitably approach Hikaru B as if he’d approach a human.

You see it in instances where he feigns sleep so that Hikaru B can go into sleeping mode, even though he probably doesn’t need to in a way humans need sleep. He fears for Hikaru B when his arm is severed while trying to protect Torao. He is used to being woken up by an energetic “Good Morning, Mr. Tora!”. In all its “not quite“ness, he’s used to his new life with Hikaru B, who has simply become Hikaru now. Not as a copy, but as something, as someone else.

To Love is Human

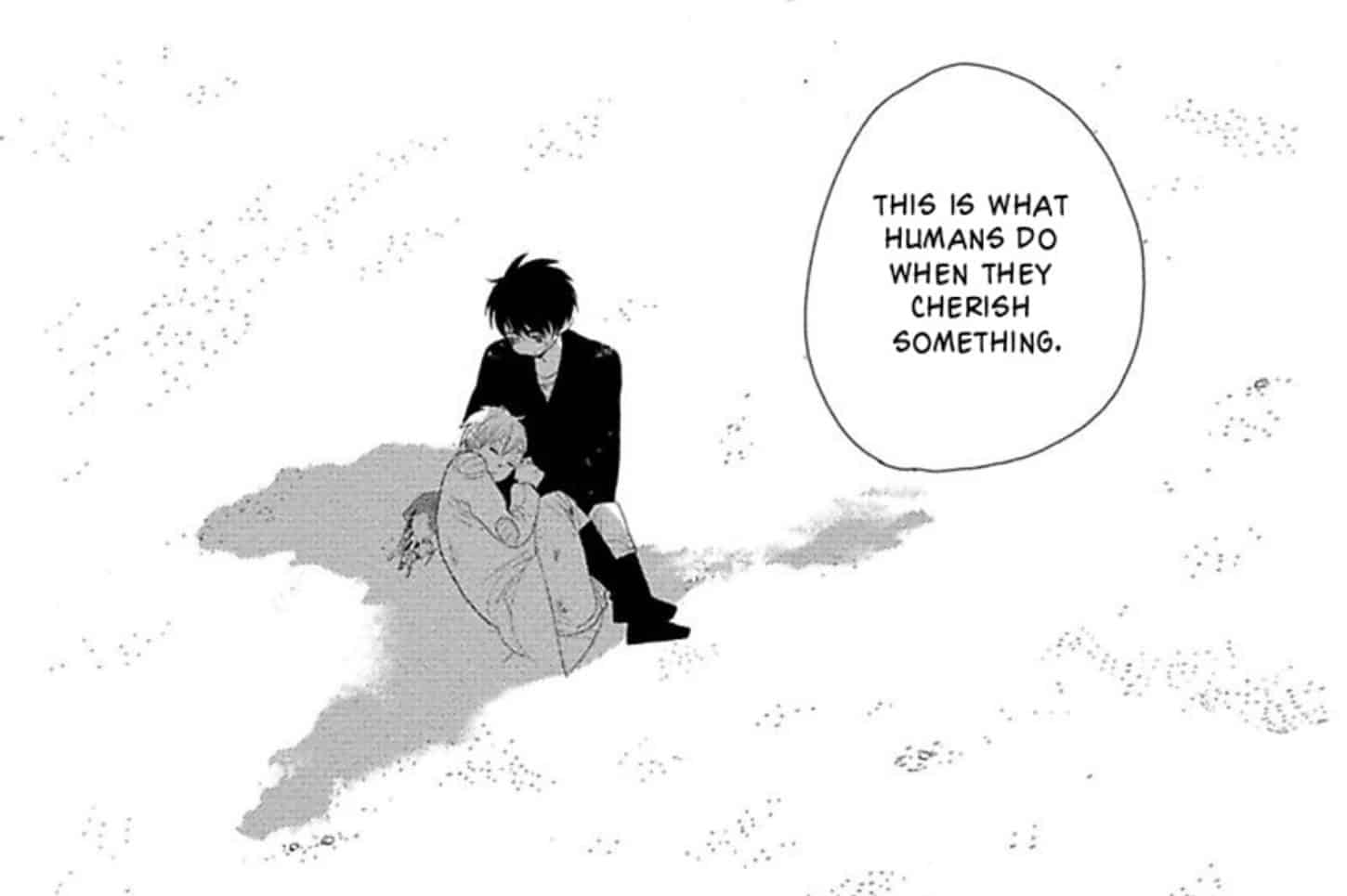

And this love story is only made possible by the humanness of Torao. It’s the capability of change, in the most unexpected of ways, and resilience to adapt even in the aftermath of horrendous events, it’s possible for Torao to heal from the pain of Hikaru and fall in love once again. I say once again because even when it carries traces of nostalgia and the baggage of past lives, it’s also a different love entirely.

We can argue whether this could genuinely be called “love”, whether humans can “love” machines, holograms, or fictional characters the way they love humans. They are easy to form an attachment to—they don’t snore in their sleep, they don’t leave you or die, they don’t act in unexpected ways, they don’t change. They never change, the same way Hikaru B will never not serve Torao. He will continue to build a sorry excuse of a house from scraps in Oze and will wait for Torao no matter how many days and nights pass, not knowing when, or if, he will ever show up. This is an algorithmic repetition. However, we cannot help but see the grandness and romantic gesture in his mechanical dedication.

Is our humanness a blessing or a curse? Who’s to know? It’s surely at the root of our anxiety and confusion with the very same things we humans create, scientific, artistic or otherwise. At the same time, our capability to change, care, create and love brings forth this unpredictable sea of possibilities. There’s no way of foreseeing exactly where we collectively will take ourselves in the far future, but our best bet is probably believing in our imperfections is, indeed, a blessing. We are human, after all.

Hiko Yamanaka’s His Romance of 500 Years is available to read in English on Bookwalker and Renta.

Want more Boys Love? Check out the Boys Love For Life column on K-Comics Beat!