If you came up reading webcomics in the 2010s and are a certain kind of nerd (introverted, anxious, perhaps prone to tea-drinking and an intense fondness for cats or strange looking dogs), you have probably come across Gemma Correll’s work. Correll, who was born in 1984, and has been working as a professional illustrator and cartoonist for over twenty years is part of a generation of millennial internet cartoonists who were foundational to the tone of contemporary swipe comics today. The early era of swipe comics was defined by the proliferation of work on Etsy, and tumblr as artists were learning how to disseminate their short-form webcomics to an exciting new online audience, with the term ‘swipe’ referring to the rather novel notion of swiping from panel to panel. Now swipe comics are best found on Instagram, X(formerly Twitter), and Bluesky, all of which now host Correll’s art. Correll, along with contemporaries such as Sarah Anderson and Simon Tofield, is often focused on the foibles of lovable animal companions(Correll’s published collections include A Cat’s Life, A Dog’s Life, A Pug’s Guide to Etiquette, and It’s a Pug’s Life), the anxieties and solitudes of being a young professional, and finding joy in spite of the drudgery of ‘adulting.’

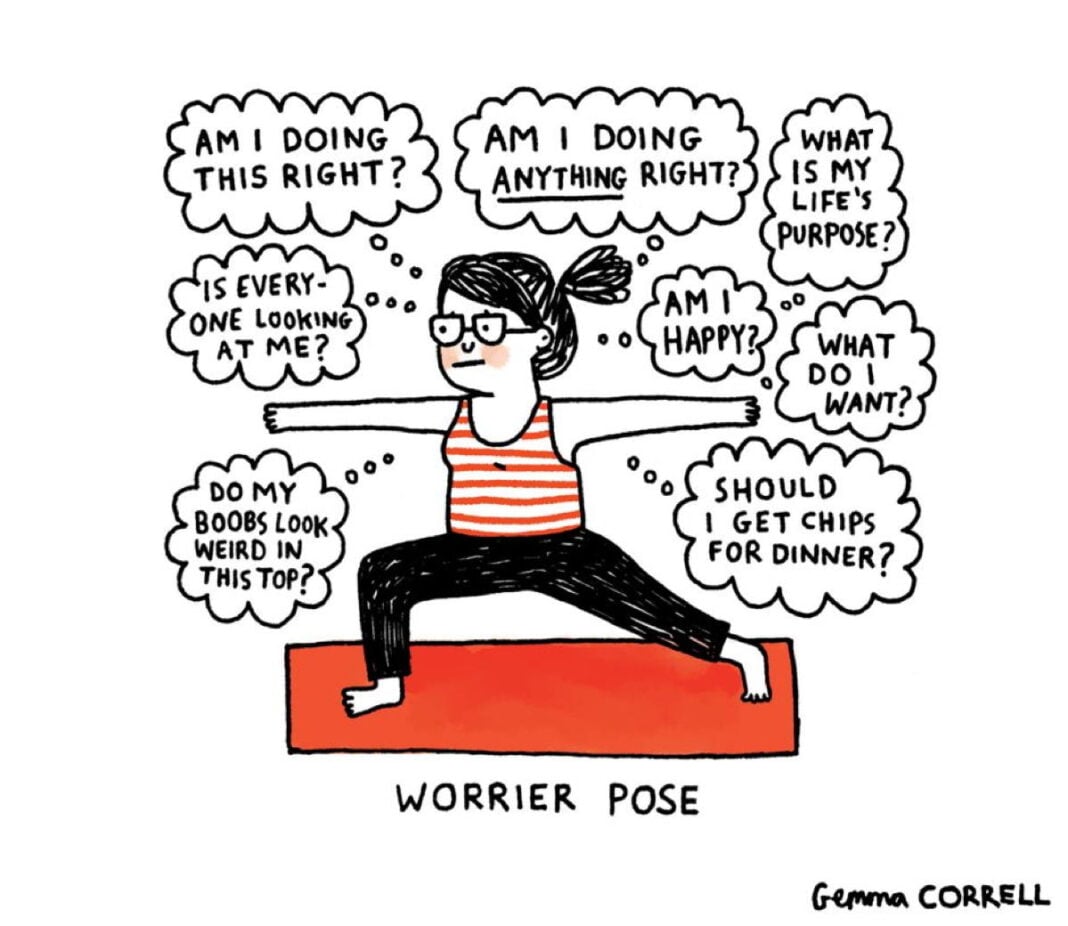

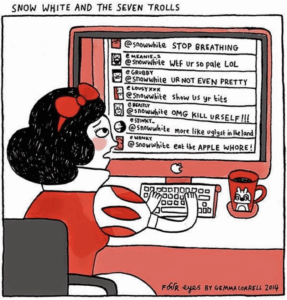

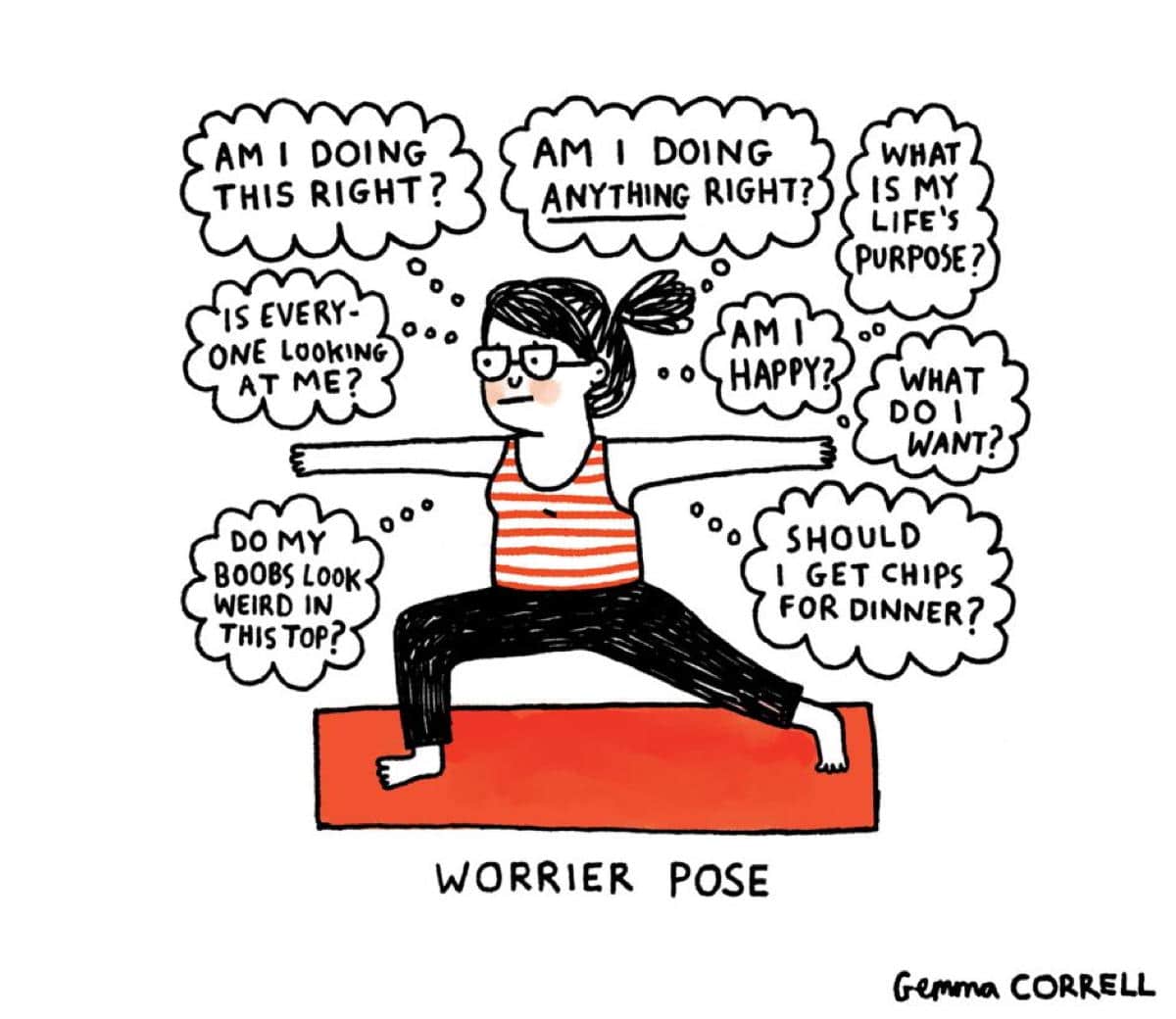

Correll’s work is also seminal to what I have chosen to call the third wave of women’s comics. The third wave runs from the 2000s to the late 2010s, with the second wave being between the 1980s and the 2000s including cartoonists Lynda Barry and Julie Doucet, both of whom Correll has listed as influences on her work. Like those of her influences, Correll’s comics consistently focus on the daily hardships women face, with some being overt feminist critiques of contemporary culture, like “Snow White and the Seven Trolls,” while works like “Worrier Pose” are charming yet honest portrayals of constant, nagging anxieties.

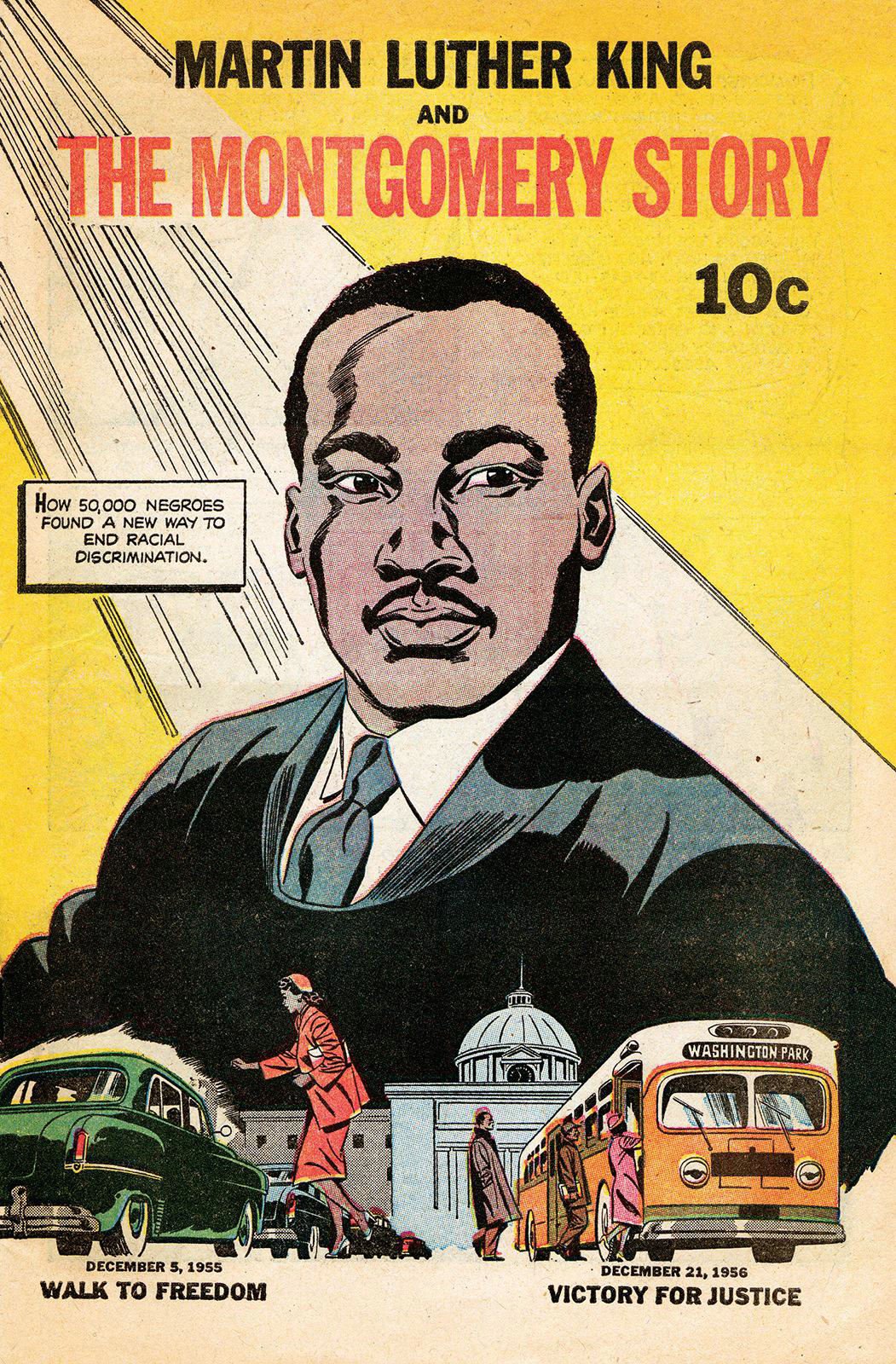

“Snow White and the Seven Trolls” by Gemma Correll

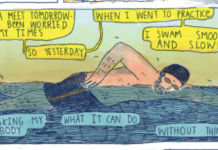

“Worrier Pose” by Gemma Correll

Despite the cute silliness of Correll’s comics, with their sketchily filled in blacks, ever-blushing heroines, and constant puns, it would be a disservice not to understand Correll as an important figure in 2010s feminist comics. What defines Correll’s third wave is the arrival of the internet as an accessible channel of mass publication. Suddenly, comics didn’t have to come in the form of floppy issues, funny pages, or graphic novels, a development which opened the door for a wide array of narrative experimentation. Works got much shorter, art became more minimalist, and cute or memeable images could be picked up by millions of viewers within days.

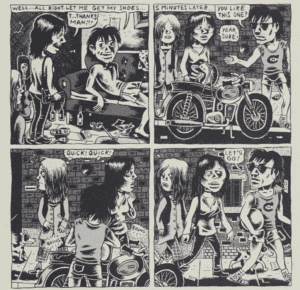

Contrast the rich, almost overflowing quality of a Barry or Doucet page with the simplicity of a Correll or Anderson piece and you’ll see the stylistic evolution I’m referring to. This simplification does not represent a deterioration of cartooning from Barry to Correll, but rather an evolution of the medium and the structures within which comics are shared.

Four panels from Julie Doucet’s 1999 book My New York Diary

I bring up this stylistic change not because it is either worse or better than what came before it, but because it highlights certain thematic through-lines which are present in the first, second, and third waves of women’s comics. Correll and Barry are all similarly concerned with sexual harassment, ridiculous female body standards, and mental illness, but Correll’s chosen form is much shorter. Most of Correll’s comics are between one and four panels presented to a reader all at once, rather than panel by panel. These comics are designed for the internet. They’re quick reads, and it is often easy to overlook the genuine interior character being portrayed in Correll’s cartoons, because of her absurd, often pun-based comedy, as in “Worrier Pose.” Her characters are almost always discomfited by something, feeling ill at ease in the world despite the blush they all exhibit, their ubiquitous stripey shirts, and their charming musses of hair. These comics are a challenging mix of the cozy-core aesthetic so marketable on the internet with an undercurrent of persistent anxiety.

The internet also had a drastic effect on the textual aspect of Correll’s work. Her predecessors’ comics were generally longer-form character driven memoir or fiction pieces, such as Barry’s 100 Demons. Such works relied heavily on both dialogue and first person narration in a manner similar to what one might find in a prose novel or memoir. Correll’s work however, forgoes dialogue almost completely, and opts instead for a pairing of a New Yorker style caption(typically a pun) paired with thought bubbles. Because of how short each piece is, the thoughts in each bubble are less about developing an individual character than they are about an easily relatable piece of inner monologue. This means that rather than following the development of a character whom we get to know and grow attached to, we are instead presented with someone a reader can immediately empathize with regardless of whether they’ve seen a Gemma Correll comic before.

Correll’s form of storytelling thrives on the internet, where attention spans are increasingly shortened, our anxieties are heightened, and we feel more alone. It is comforting to recognize, in a bite-sized fragment, that someone else in the world is worrying about when the last time they showered was, and whether their significant other can tell it was a week ago. Correll’s cute, blushing girls with crumbs in their bras tap into the strangeness of a world in which we must all present as perfect online, even as the internet eats away at our daily dose of fresh air, communal kindness, and stability.