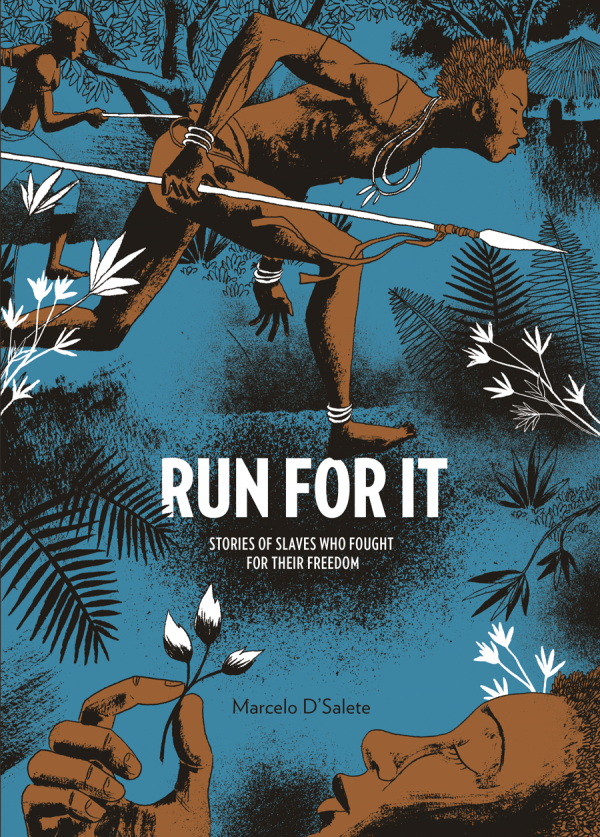

Brazilian cartoonist Marcelo D’Salete offers a different view of slavery in Run For It, focusing on Brazilian plantations and slavery, and celebrating resistance in that context. It was a 300-year-old institution in that country, with black Africans and indigenous people all victims. At one point, Brazil had imported more African slaves than any other country in the world, and it was the last western country to do away with the ugly, destructive institution.

D’Salete’s stories mostly center around Mocambo, which were escapee settlements that slaves could flee to, and the history of Brazilian slavery is scattered with instances of insurrection on a small scale. D’Salete has gone back to the historical documents and slave narratives to capture these everyday transgressions that, together, create a more complete picture of a sick society at war from within.

In “Kalunga” the frenzy of desperation, the vitality of connection, and the way the system can callously break that, is examined grimly as Valu tries to convince Nana to escape with him when he finds out that he is headed for another plantation. His love for Nana might be his only possession, and is obviously the only thing that has kept him going, but the question becomes one of ownership. You can own a person, but do you control the intangibles inside them, the emotions? And if feelings eventually manifest in the physical, can’t even the darkest acts stand as proof that no one is ever completely property?

In “Sumidouro” the slave woman Calu becomes pregnant, and the intangible in this case becomes touchable — a baby. Here, D’Salete asks similar questions of ownership and control but expands them. We already know the slave owners felt their ownership was strong enough to sell humans as they pleased, but what about other ways to get a human out of your sight? What if there is no motive but control?

“Cumbe” focuses a burgeoning slave rebellion clandestinely planning the day of their action. But it’s already fraught with suspicion and fears of betrayal, and this paranoia may be its undoing, but not in the way you expect. The forces such a rebellion opposes is far greater than anything that could rot it from the inside, and D’Salete provides a stirring depiction of the hopeless war being waged here.

“Malungo” is in many ways a tale of revenge — Damiao has long since escaped the plantation, but an oncoming war to punish slave owners gives him the opportunity to return and settle unfinished business that haunts him. D’Salete wraps this tale around the presence of a folkloric monster that creates the idea of danger and evil for people to heed, even as the real danger and evil have proclaimed those same people possessions.

D’Salete provides little narrative nor the specific context in his tales, preferring to drop the reader directly into the situation and move along with the characters in dire, frantic, heartbreaking situations. D’Salete is cautious with words in general, and it helps to have a careful eye as his stories unfold, mixing the personal histories that bring his characters to the place they are with the dynamic action that each situation sparks into. It’s an electric depiction of the situation, built on an emotional presentation that piles on the frenzy that the characters find themselves in.

Run For It settles into dark historical moments in a world filled with extreme darkness over millennia, and D’Salete isn’t interested in intellectualizing any of it. Instead, he wraps the human emotion of the events around the reader, personalizing the larger experience through smaller instances of fear and despair. If we can’t understand right and wrong, surely we can see clearly through raw human emotions.