Earlier this year, Soaring Penguin Press published the first complete English translation of Régis Loisel’s classic French series of bande dessinée, Peter Pan, a dark prequel to the JM Barrie fairy tale that pushes the boundaries of Neverland’s sinister origins.

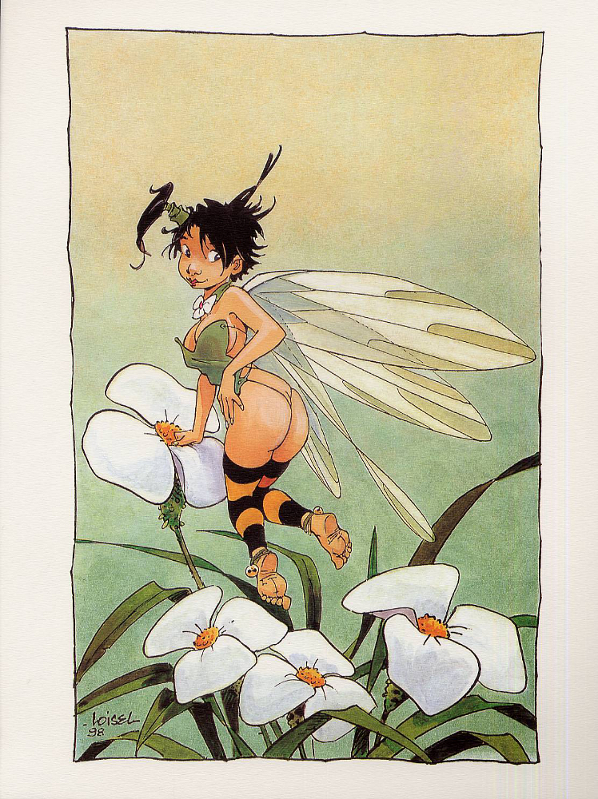

A very adult tale, this Peter Pan has won critical acclaim and fame in native France where Loisel’s Clochette – Tinker Bell – is as familiar a sight as the Disney starlet. Yet with its arrival on our shores many UK reviewers were left shocked by the sexual and vulgar content – most notably perhaps by Tinker Bell’s voluptuous appearance, and Peter’s insults towards her in the first chapter – “bitch!” “slut!”.

But this prequel to JM Barrie’s classic, to the play and to the Disney animated feature, is perfectly in keeping with all of its predecessors – the final line from Barrie is after all the sinister, “and thus it will go on, so long as children are gay and innocent and heartless.” By taking the subtext out of the shadows and into the spotlight, Loisel’s Peter Pan is infinitely more enjoyable.

Darkest Peter

The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up is familiar to many people as the green-clad fairy friend from Disney’s 1953 film. Re-released regularly and with co-star Tinker Bell more recently becoming one of the company’s star merchandising attractions, it’s easy to forget the somewhat troubling aspects of the adventure story.

As a very young child I reveled in the world of Neverland, aspiring to be a Lost Boy and to fight pirates. But it wasn’t long before the film began to cause a deep discomfort, for reasons that my young mind could not quite fathom, other than the fact that there was clearly no place for a female Lost Boy.

Often discussed alongside Alice in Wonderland due to the Disney connection and explicit Freudian undertones, the two held very different places in my childhood (and adult) heart. While Alice had the more obvious sexual subtext of falling down holes, opening doors, drinking strange liquids from bottles and so forth, there is no actual maturation – instead the focus is very much on the agency and spirit of Alice the child as she willfully and stubbornly travels through her Wonderland (it also led to my firm belief that as soon as I was old enough I was having some of whatever drugs Carroll was having).

Wonderland might be a surreal and dangerous place, but it was Alice who decided her own fate and destiny, and I found the madness of that entire world completely enthralling.

Peter Pan on the other hand had no place for women that I could possibly see myself wanting to aspire to, and ended up in my “this freaks me out” pile of videos alongside Disney’s Pinocchio and Fantasia. The women in Neverland (and in the real world) had very rigid roles to play: the mother – Wendy and Mrs Darling; the jealous mistress – Tinker Bell; the dangerous whores – the mermaids; the unrequited and silent adorer – Tiger Lily.

Neverland tells us that being sexual is to be terrible, as the mermaids try to seduce Peter and drown Wendy, and that it leads to jealous and murderous rages. The correct way to be female is to aspire to be a mother (the wife part is unimportant in comparison), but not to wish boys into men. Rather the men present, both in Neverland and the real world, act as childish boys regardless.

The only woman allowed to act out her feelings with no apparent consequences is Tiger Lily, who is silent and portrayed as the exotic and sexual other, in stereotypically racist form.

(Like Alice, Wendy also appears in the sexually explicit Lost Girls by Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie, a book that deserves far more than a note here!)

Enter Loisel

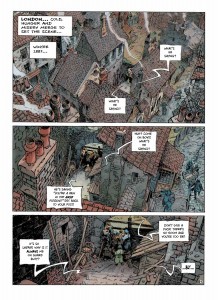

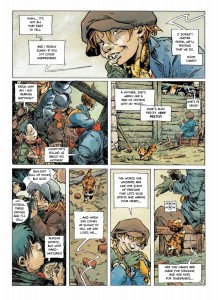

Apart from Wendy and the Darlings, all these characters appear in Loisel’s more detailed look at this fantasyland. Opening in the slums of London in winter 1887, “… cold, hunger and misery merge to set the scene.”

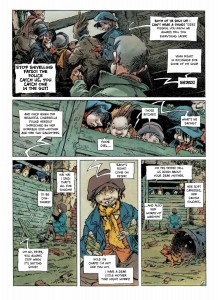

These lost boys are crowded together to hear a story from a young boy who sits alone, free of the alley and pictured against the open sky. The bucktooth storyteller is speaking of Cinderella and her ugly step-sisters (“those bitches!”) before reminiscing about his dear mother who he must return home to. The orphans listen entranced at his description of an angelic woman who surrounds him with honey kisses and love.

This Peter is the storyteller, rather than the story listener, whom orphans press against gates and windows to hear. As Peter rushes home, he stops by an inn where an old man feeds both his appetite and imagination. Mr Kundal has taken a fatherly interest in the boy, teaching him to read, write and count, and most importantly, to tell stories. The importance of his influence is underscored both by the surroundings of Peter’s life and the true face of his darling mother.

Accosted by a prostitute on the way home, who offers to mother him with a free nuzzle on her heaving breasts, Peter flees yelling “Dirty adult! Dirty adult!” before being sent out into the freezing night once more by his violent and alcoholic mother. Forced to expose himself for the bottle of brandy that his mother desires, Peter is then near-raped by a foul drunken man, who in turn is attacked by feral dogs that rip his penis clean from his body while Peter cheers his death.

This then, is not the world of Barrie. The three Darling children, spoiled and prim, would not recognise these streets, nor these events, and we have dispensed with the pretence that Peter is half-bird. But this is the Peter before Neverland, the Peter who came to have such a strong mother-fixation and desire to never grow old, to never grow into a dirty adult. Pre-sexual and protective of his innocence, it is this Peter who Tinker Bell finds, thrown from his home and shivering on the streets.

In his six volumes (London, Opikanoba, Tempest, Red Hands, Hook, Destiny), Loisel goes on to introduce all the principal characters of Neverland – plus several new cast members – and to join the dots between his book and Barrie’s tale. We learn how Peter has the permanent ability to fly, the significance of his adoption of the name Pan, why the crocodile ticks and what his purpose is, just why Hook is so obsessed with Peter, how the Lost Boys came to be, and why Tiger Lily loves Peter. Most importantly we learn the potency of the islands power to make its inhabitants forget their adventures and motivations, forcing them to repeat their mistakes and discoveries in a perpetual loop.

This cleverly explains any and all repetitions between Loisel and Barrie, as well as underlining just how terrible some of the acts on the island are, only to be forgotten by all. Tinkerbell may try to have Wendy killed later, but now she goes much further in her murderous tantrums. Peter too has blood on his hands, and the ease in which the Lost Boys suggest killing the inconvenient is chilling.

Peter’s unquenched rage towards women and his fixation on the ideal mother is a particularly strong theme throughout the book. From his early disgust at the prostitutes on the streets of London to his dismissal of the sultry sirens in Neverland, his contempt of girls and fear of female sexuality is a perfect mirror to the jealous rage of his Tinker Bell. What threatens Peter, she also perceives as a threat, and takes extreme steps to protect their own relationship – Tinker Bell being perhaps the sole female character who has won Peter’s trust.

Murder Most Horrid

But those post-Dickensian origins lay another thread throughout this book – that of Jack the Ripper. While at first seemingly out of place in what would otherwise be a straightforward prequel, the stitches are more easily spotted on a second read. A traumatic end to one element of Peter’s past is left perfectly ambiguous, portrayed quite literally behind closed doors, as Peter returns to the real world to fetch a doctor’s bag to save a Neverland friend.

Meanwhile a man named Jack, a doctor, fleeing the scenes of various murders, begins to see Peter as an omen of ill will. Struggling to remember his deeds at the times of the infamous murders, Jack concedes that he must be mad, and in his madness he forgets all and the murders stop. At the same time Peter makes his last trip to London after another violent reaction to a prostitute trying to entice him, one Mary Jane Kelly.

The ambiguity is deliberate on Loisel’s part, and subtly hidden, but as the book slowly unwinds we have seen just how disturbed, and violent, Peter truly is. The problem being that Peter himself cannot remember.

But if Peter is indeed responsible for such awful crimes, it would be the result of the hatred and dismissal of women in Barrie’s original drawn out to its furthest reaches.

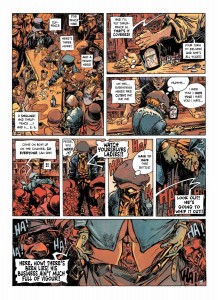

Loisel’s Neverland has a dark centre, both literal and implied. Opikanoba lies at the heart of the island, a place “haunted by our worst fears and phobias! An abyss packed with our greatest fears.” If Neverland is made of dream-stuff, then here is where the nightmares stir. And yet other elements of the island clearly correspond to Peter’s own fears too – the topless mermaids with their shapely assets on display, cooing to Peter to come and play (note the name of the London pub Peter frequents); the violent and fixated Hook who begins as hero to the young boy; and multiple threats of sexuality or romance.

That Peter can control these elements holds the difference, but the sexuality that surrounds him is still all too palpable. Female sexuality only of course, as dangerous or subversive to our protagonist, with male sexuality almost completely ignored. What little is shown is either violent or threatening – the man who attempts to force himself on Peter only to have his penis ripped off by frenzied dogs; Peter’s shame as he is forced to expose himself in a pub to earn alcohol for his terrifying mother; and Captain Hook’s quite bizarre angry outburst, “You’re pulling my cock again, with your stories!” (what?).

This is the legacy of Barrie, who tied up all his female characters with sexual desires or dangers, in favour of letting boys never grow up. The often commented upon fact that in the play (and subsequently the Disney film) the same actor played both Mr Darling and Hook overlooks the fact that Barrie was originally quite insistent that it be the actress who played Mrs Darling who take on the Hook role, once more tying the female and her intrinsically adult ways to a dangerously seductive threat while the Lost Boys and Peter remain pure and innocent.

(Indeed the Scottish author and playwright, as with Carroll before him, has been surrounded by suspicion not for his printed works, but for his own personal reputation. Like Alice, the characters of Peter Pan are based on children befriended by the author, though their lives subsequently took very dark and tragic paths. The darkness that surrounded the mythology of the book has intensified in more recent years, with pop culture icons likened to the titular character for their associations with both children and their own childhood-fixation.)

The Gorgeous and Grotesque

Loisel is no stranger to drawing naked female bodies, and he does so in Peter Pan with great gusto, producing nubile bodies of all shapes and sizes upon the page. His character work borders on the ugly for many (though clearly not for Clochette’s fans!) as he eschews the Disneyfied faces and slim bodies in favour of expression and caricature.

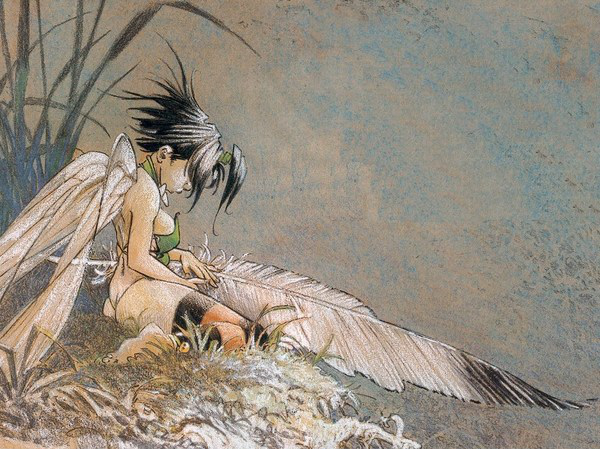

The Tinker Bell who in her Disney introduction measures her hips and expresses dismay is here clad in a tight fitting leaf that barely covers her huge breasts and doesn’t even attempt to hide her pert buttocks. Sensuous upon the page, and comfortable with her looks, this Tinker Bell still perfectly resembles Barrie’s creation: “It was a girl called Tinker Bell exquisitely gowned in a skeleton leaf, cut low and square, through which her figure could be seen to the best advantage. She was slightly inclined to embonpoint.”

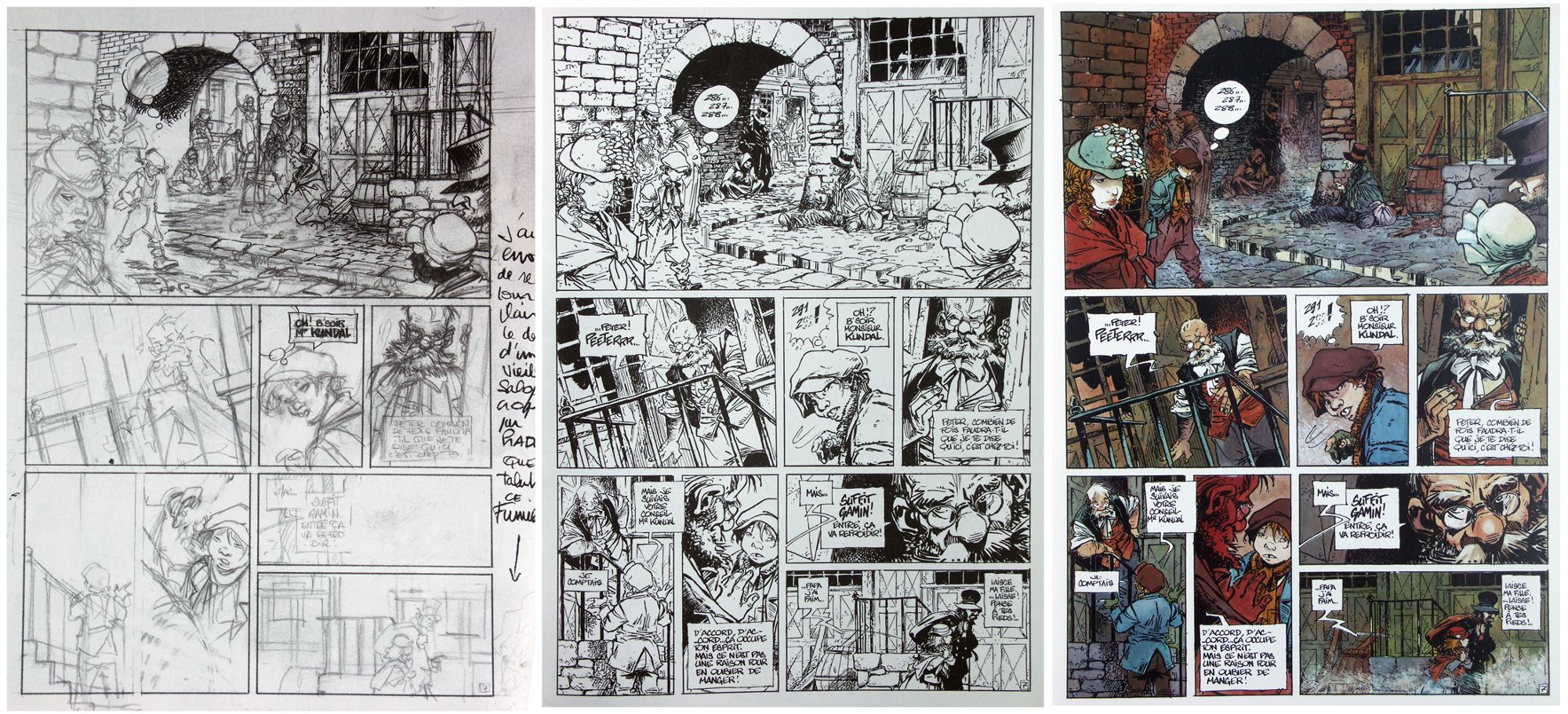

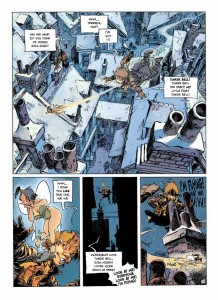

Loisel’s mastery of the human face and form works wonders throughout and is of particular blessing given the large cast. At no point are any two characters confused with each other, even when shown at a distance or half hidden. The artist also employs that wonderful tradition of using richly realistic and sumptuous backgrounds with more cartoonish characters to better juxtapose the story. The characters are all the more relatable, while the landscapes in both London and Neverland are lavishly gorgeous.

The difference between London and Neverland is jarring, as it should be, but the split colour palette is particularly effective. London is harsh blues and oranges, while Neverland is a chilled yellow and green. The colours are glorious, and coloured traditionally by the artist who prefers to work sensitively with very few colours, but it is the inked lines that really deserve high praise – vibrant lines stand proud on the page (while subtly erecting a magnificent backdrop), full of energy and character.

Loisel’s love for the female form is, again, highly obvious and beauty shines through even the most malevolent of women throughout the story. The artist spoke once of his way of “drawing women caressing the tip of my pen” which perhaps explains his skill best – the cult status of his Clochette amongst men and women alike is testament to the magic that he works. The majority of women in Peter Pan are buxom to the extreme, but not in a particularly unrealistic hourglass style – these women have bellies and thighs to match.

Having seen images and scans from the French editions online, I also have to praise the high quality of this particular collection – printed oversize here too, and at 372 pages, the print is clear and crisp, showing the artwork to its full potential. A marvellous tribute to the esteemed Loisel, who won Angoulême’s Grand Prix in 2003, famed artist of fantasy classics La Quête de l’oiseau du temps (The Quest for the Time-Bird, published partially as Roxanna in English) and Pyrénée amongst others, who also provided visual development art for Disney’s Mulan and Atlantis.

My one complaint is about neither story (which answers much and asks more) nor art, (which both compliments and counterpoints the text) but rather the sometimes unfortunate speech balloons placement. While most frequently requiring the reader to read the balloons vertically in each panel, from top to bottom, occasionally this is changed to a horizontal order, from left to right. These changes result in great confusion when reading, pulling the reader from the story in order to attempt to re-navigate the dialogue.

Trying to predict this change of order is impossible, and when combined with long-distance shots can often make it unclear as to who is saying what. The reader requires clues in the dialogue itself in order to make sense of some conversations. This is not a frequent event, but it does get frustrating at times.

Yet these same balloons can often burst out of the panels in their intensity, spilling off the page and into the gutters of imagination with such energy that much can be forgiven. The ploy too of balloons creeping across to neighbouring panels makes transitions appear effortless – particularly in scene jumps but also in subject.

Sound effects are used extensively with a great sense of fun, which alongside that balloon energy helps to offset the sheer wordiness of the book. At a glance, though never in the reading, some pages become incredibly text heavy, but silence is also used effectively.

Happily Ever After

One final criticism is once more tied very strongly to both Barrie’s original and the Disney adaptation – that of overt stereotypical racism. The “gigantic black”, the only unnamed pirate by Barrie is here portrayed in the same ridiculous animalistic fashion as employed by Hergé in Tintin in the Congo, while the “Indians” are all near-identical savages (Tiger-Lily is however given a voice).

While one could give the reasoning as being bound to the rules of the book it is set before, or simply ignorance on the part of the creator, the former is no excuse at all and the latter even less. These racist caricatures are used not to comment on the racism of Barrie or Neverland, but simply as decoration. The misogynist attitude of Peter (and others) and the very sexual portrayal of the female characters of course does come from the original text, but it serves a major purpose in the story, particularly given Loisel’s exploration of just how deep the hatred lies. In contrast, the racism lies loose and afloat.

It is an unfortunate inclusion in an otherwise splendid book, and I would dearly like to know if Loisel has offered any commentary on the matter.

This is, at its heart, a very personal Peter Pan. While Loisel is indeed one of the most renowned and influential comic artists in France – his work, alongside Moebius and others, helped set the stylistic standards of the modern bandes dessinée – it is rare that he produces projects where he acts as both writer and artist.

Other artists will surely sympathise with the 14-year timescale of such an endeavour, created alongside his other work, but for it to take a further 9 years to gain an English translation is a damning testament to how difficult it is to acquire the rights of European comics for the smaller English-speaking comics market.

Regardless of your opinion on any of the previous Peter Pan adaptations, I highly recommend giving this Peter Pan a try. It makes for a gorgeous read, both thrilling and heartbreaking, and the ambiguities and mysteries are perfectly intriguing. The criticisms I have are by no means forgettable, but this addition to the Peter Pan mythology is still by far the best yet.

Oh, and bring some tissues for a wee cry. You’re welcome.

All credit to John Anderson at Soaring Penguin Press for publishing such a luxurious collection!

Laura Sneddon is a comics journalist and academic, writing for the mainstream UK press with a particular focus on women and feminism in comics. Currently working on a PhD, do not offend her chair leg of truth; it is wise and terrible. Her writing is indexed at comicbookgrrrl.com and procrastinated upon via @thalestral on Twitter.

Nice piece! I think there may be a typo in the 3rd paragraph, though—did you mean US instead of UK?

Duh, nevermind, my mistake!!!!

Great write-up!!!!! the story of PP is so interesting to re-read as an adult… i love this retelling soooooo much. was given the heavy metal volumes to read in college and was so inspired! (though told that it may be too extreme for my “delicate sensibilities”, being a girl and all LOL) loisel is one of my top fave artists! I’m so pleased there’s this translation now! It looks so good, too!!!!! Can’t wait to get it! x

Both Peter Pan and J.M. Barrie are complicated, and anyone who thinks of Peter just in terms of the Disney movie would be surprised by the darkness of the original play or novel. For example, in early drafts of the play (before an encounter with pirates was added as an in-front-of-the-curtain scene to allow for a set change) Peter was the villain of the story. Barrie was very conflicted about Peter, using him to represent both the brother that his mother had loved more than him, and the Davies boys that he was so fond of himself.

It has such a fascinating history. I went back and re-read the novel and play notes after reading this book, to try and remember what bits came from where.

I’d love to read a good biography of JM Barrie but criticism of those that exist seems quite divided.

Wonderful review of a must read graphic novel!! BRAVO to John Anderson and his team for bringing it to life in the English translation and to Loisel for making it so in any language!

http://www.soaringpenguinpress.com/publications/graphic-novels/loisels-peter-pan/

Hmmm… how close is Neverland to Pleasure Island?

And which island contains Castle Rock?

The best biography of Barrie I’ve found is Andrew Birkin’s J. M. Barrie and the Lost Boys, which relies heavily on original sources (e.g. personal letters, the last surviving Davies boy) and doesn’t engage in much speculative armchair psychiatry. It neither idolizes or demonizes JMB, and it’s a good read. (Birkin’s a screenwriter by trade.)

Don’t even bother opening Piers Dudgeon’s salacious conspiracy-theory cash-grab.

By the way, I’ve set up a fairly extensive online encyclopedia about JMB and Peter: http://Neverpedia.com

P.S. for those more cinematically inclined: The mustacheless Johnny Depp movie was a nice bit of Hollywood inspired-by-a-true-story storytelling, but Birkin’s BBC mini-series with Ian Holm as JMB is also far better as biography.

Comments are closed.