by Alex Dueben

For the past few years, one of the funniest, strangest and most inventive webcomics around has been crafted by Sydney Padua, a Canadian animator living in Britain, who has been telling strange fictional adventures (and misadventures) of Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace. Admittedly, 19th century mathematics does not seem like a logical source for an ongoing webcomic – much less one that’s consistently laugh out loud funny – but Padua has managed to do just that.

This spring Pantheon released “The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage: The (Mostly) True Story of the First Computer” and Padua just completed a tour through North America and she recently spoke about the comic and her process.

Alex Dueben: Just by way of introduction, Sydney, what’s your background?

Sydney Padua: I’m an anonymous toiler in the mines of feature animation. I’ve been an animator for about twenty years. I went to Sheridan College Animation School in Toronto. Before that I studied theater history and design at the University of Alberta. I was very lucky to do that at the exact right time. When I started studying animation it wasn’t really a thing. Disney was doing some films, but that was about it. When I was in the middle of school the boom happened–Toy Story and Jurassic Park–and then suddenly every animation grad could get hired in Hollywood. I went to Warner Brothers and was a 2D animator and artist for almost ten years. Then 2D animation collapsed so I had to learn computer animation–with great reluctance–but now now I’m pretty happy working as a CG animator. I’m doing VFX for big movies.

Dueben: Where did “The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage” start? Correct me if I’m wrong but it began as you doing a short biographical comic about Ada Lovelace?

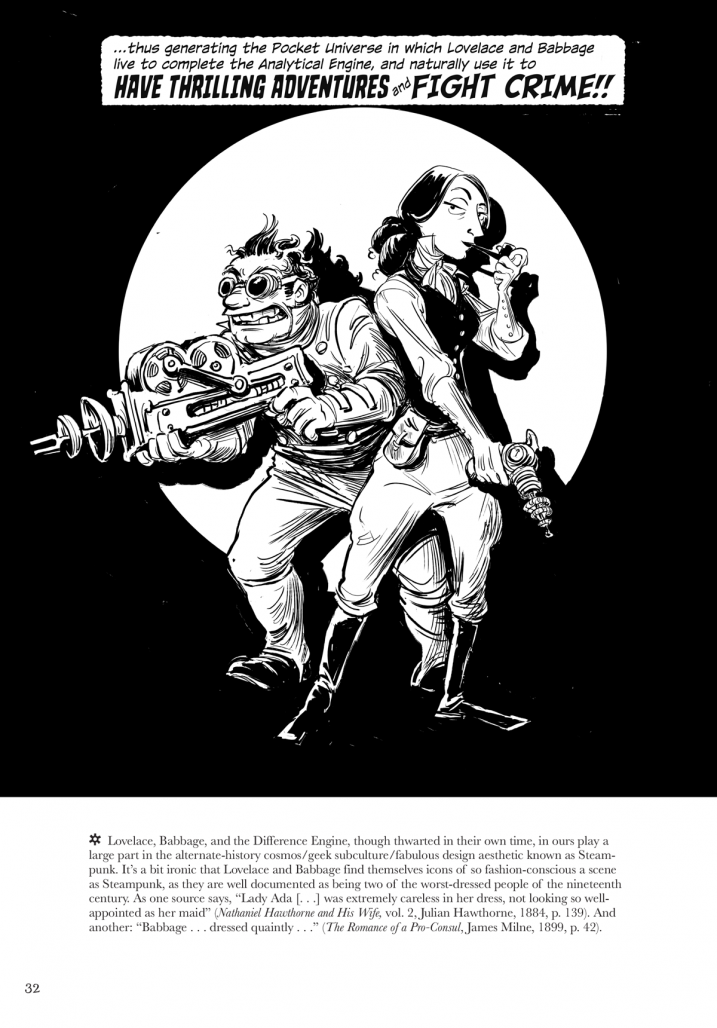

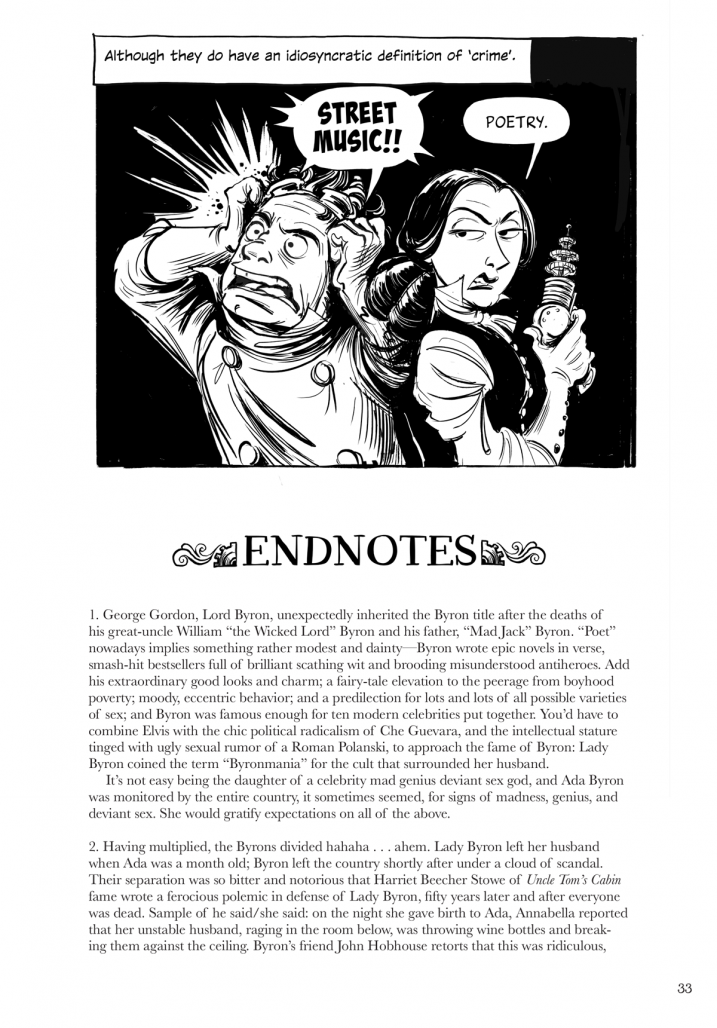

Padua: It started as a joke. It was literally a joke. I was in a pub–actually strictly speaking I think I was in a wine bar but it sounds better if it was a pub–with my friend Suw Charman, who started Ada Lovelace Day, which is this women in computing day. She was like, you’re a woman in tech you should do a comic! I was like, I’ve never even heard of Ada Lovelace. I went to wikipedia and was like, oh my god. I dashed off the comic in an evening or two. This punchline is that they die and it’s really boring but that’s too stupid an ending so I drew them in these steampunk outfits fighting crime. That was completely a joke. I didn’t have the smallest intention of doing another comic. It turned up on the internet the next day and people on twitter were like, this person is going to do this comic. [laughs] So then I felt obliged.

Dueben: You have a great comic explaining what they define as crime–for her, poetry, and for him, street music.

Padua: And it’s all true! [laughs]

Dueben: I first heard of Ada Lovelace about 15 years ago because of this Tilda Swinton movie, “Conceiving Ada.” At the time I assumed that she was obviously fictional because if she were real, everyone would know who this woman was.

Padua: I know. It was so bizarre. I still remember reading the wikipedia article and saying, you’re joking? It just got more and more crazy. I still find stuff through research and I go, you’re making this up! [laughs] This cannot possibly be true. I couldn’t believe that nobody had done an ongoing series with her or really used her as a character. I hadn’t read “The Difference Engine” when I started the comic, but she’s not really a character in it. She’s there, but they don’t make anything of her, which I thought was weird. She’s perfect. She’s like Batman. She’s got all this angst. Babbage is fantastic. He’s such a personality. He was such a funny guy. It was such a gift. There were gags lying around.

Dueben: How much of the strip came from research? And what was push and pull between doing more research and making more comics?

Padua: The research definitely drove the comic. I would say most of the time I was drawing the comic because I wanted to be able to footnote it with a really amazing thing I found. The comic was completely improvised. This may be obvious, but I don’t sit down and write a really careful script. I just went online and completely improvised episode to episode. I was just bouncing off the stuff that I was reading literally as I was drawing the comic. Google books was a big gift. Around the same time I started the comic they were just dumping all this 19th century stuff online that had never been indexed before. I was finding stuff that proper actual scholars had never seen–and I knew they’d never seen it because it was often contradicting stuff that they were writing! [laughs] It’s not like some official obituary, it’s some guy in some town paper writing a letter about how I met Babbage. It’s so fresh and so alive and I just found it incredibly inspiring. It was like this little wormhole into the past.

Dueben: I loved the story with George Eliot. Where did idea come from, because its one thing to say that it involves Eliot meeting Babbage and Lovelace. That conjures a certain idea for people, but you discuss how computers process information and there’s a lot going on besides just, isn’t it cool these three historical figures are meeting.

Padua: I knew I wanted to have a civilian, basically, collide with the engine. I’d done a bunch of stories with Babbage and Lovelace and of course they know everything and they’re these super-geniuses, but I’m not a computer expert of any kind. My own experience with computers as a 2D animator is that it is this fiendish torture device that they make us animate on. [laughs] It’s incredibly complicated software, it crashes all the time, there’s always some bit that you’ve never seen before with fifty buttons. Even the experts on this software don’t know how it works. [laughs] So despite not being a computer person, I have a lot of experience in my day to day working life of the bafflements of extremely complicated software. I called the George Eliot episode “User Experience” because it’s about really terrible user experience. [laughs] That is absolutely me lost in the software that I have to use for work every single day.

Dueben: You draw this massive building housing the engine dominating the city of London and I kept picturing it as the power plant that became the Tate Modern.

Padua: I’m not too far from the Tate Modern. If I was better at drawing backgrounds it would have been even better.

Dueben: In the book’s introduction, you’re self-deprecating, saying that you’re not a comics artist and you didn’t know what you were doing. What was it like learning to do this as you were doing it?

Padua: It was actually super fun. I mean I’ve never done a comic. I had done a fan fiction comic very loose and messy years and years ago. It was really fun. What’s nice about comics is that if you can’t write it, you can do a drawing and if you can’t draw it, you can write something down. I’d been thinking I’d like to do a comic properly. Having come from 2D animation and features, drawing is quite stressful. There’s performance anxiety and you’re always being judged and corrected on your drawing all the time. It’s great training obviously, but at the same time despite always wanting to do a comic, I didn’t want to do an “official” comic because then my drawing would be on display and everyone would be like, your drawing is terrible. This really liberating thing happened with “Lovelace and Babbage,” which is I didn’t think anyone was actually reading it. I never mentioned it to anyone at work. It was just a complete playful space where I was never even thinking about the drawing. I was just playing around. The drawing is super loose and rough. You just go into the challenge of constructing the panel and all that like a game. I had all these rules. I had to have a gag every single panel. Lovelace and Babbage always have to cause the problem and then solve it. I had this whole list of rules and it was this very playful space. I think that’s the best way to learn, if you can turn something into a game.

Dueben: Coming off of animation where you have to be on model all the time, is the loose style of the comic more of how you draw?

Padua: It took me years to get animation out of my drawing. In the process of learning to animate, there’s a lot about getting rid of your own style and being able to impose the official style. You get a ton of really useful tools, obviously, in terms of craftsmanship, but I think you lose a lot of individuality. I had to go back and unlearn everything. To let myself not construct something, but to just draw the gesture and leave it. That was a really long learning process. It didn’t start with the comic. I’d been trying to do more life drawing and find my own style for a long time before that.

Dueben: The comic is just where it came together.

Padua: Yeah this is the arena where I could really use it. I really resented going into computer animation at first. Because you worked so hard to learn this tuff and then it’s like, oh you don’t need that. At the same time, I realized that my drawing is mine again. It doesn’t have it be this official tool that has to conform to all these rules. Now it can go back to being my own.

Dueben: You said that you’re not much for backgrounds but the body language, the clothing, the Victorian touches, technology, animals–are these the things you like to draw? This is what you randomly sketch?

Padua: About fifty percent ponies. [laughs] And funny gestures.

Dueben: You did a lot of life drawing and spend time focusing on body language.

Padua: I studied theater, which was more on the theory and back stage side of things, but my specialization was mask theater and mime. I guess that is a line that runs through animation and the comic. This caricatured body language is something that I enjoy playing with.

Dueben: When you started out, did you have a model for what you were trying to do?

Padua: Asterix. I wanted to do Asterix but in the Victorian era with computer jokes.

Dueben: I wouldn’t have guessed that, but now that you say it, I can see it.

Padua: [laughs] I’m a complete Asterix nut. If I think back when I was like twelve and copying comics, I was copying Asterix obsessively. Especially the horses because he was amazing at horses. Asterix was a big one. Will Eisner was another big influence. I like old comics. Asterix and Tintin and Milton Caniff. Mad Magazine. Groo. I inherited this giant pile of really old Mad Magazines with Jack Davis and Sergio Aragones.

Dueben: When you signed the book deal with Pantheon, what kind of conversation did you have about what to include and the structure of the book?

Padua: My entire brief was basically they wanted the comic poured into the book. They wanted what I’d already done. I had actually talked to another publisher in a very informal way and they were like, of course you can’t do what you do in the comic because it’s too weird. And I completely agreed with them. To me the idea of doing the comic with all the footnotes, these weird super inside jokes and a ton of super technical details just seemed like a stupid idea. Of course I shouldn’t do that.

But Pantheon and Dan Frank were like, it needs to be exactly like the comic. It needs to be as eccentric as possible. Just do what you do. He left me alone, which was terrifying because I had no clue what I was doing. I just cried a lot and tried to somehow make it work. Basically I was trying to keep the spirit of the website in book form so obviously a lot of the structural stuff had to be quite different. The footnotes had to be there on the page. If you just extracted all the comics and ran them, I don’t think it would be very good. The comic is existing in this space between the footnotes and the drawings, if that makes sense.

Dueben: It does. I would argue that the footnotes are as important as the dialogue.

Padua: It’s not a straight comic with footnotes. It’s a whole different thing. I was desperately trying to find somebody who had done the same thing so I could see that it worked. But no one had–which proved to me that it wouldn’t work. [laughs] I hope it works. It was a leap of faith to make the book that I would personally want to read. For example, I always want to see the whole document. This is super nerdy but I hate it when people quote half a line and then contextualize it themselves. The more secondary histories I read the more I’m like, just give me the document, man! I don’t want to hear you paraphrase because you’re probably distorting something. That’s why I have the appendix. I could have easily made that 300 pages. [laughs] The engine diagrams probably took me five or six months alone, but you read all these books and even serious ones–especially quite serious ones–and you’re like, what does it look like? No one had done that, so I did. It took me ages so I hope people appreciate that. It seems a very strange book to me because there are all these funny gags and comics and poor Babbage has this as the first visualization of his analytical engine, in this random comic book.

Dueben: I couldn’t think of anything that worked quite like this, but David Foster Wallace wrote a number of fiction and nonfiction pieces which had footnotes and endnotes, and they weren’t an addendum, they were an essential part.

Padua: Interesting. I haven’t actually read David Foster Wallace. I was thinking of Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell which is one of my favorite books from the past ten years. That’s an imaginary history and the footnotes again create this tension between the text and the footnotes. I just really love footnotes.

Dueben: I do wonder about people who pick it up. Will comics people go, what are all these documents? Will technical people complain about the comics?

Padua: Everyone’s going to hate me for different reasons! [laughs] There was zero interest in doing a marketable commodity.

Dueben: So what’s next for you?

Padua: I have no idea. Everyone’s asking me this and we’re in crunch on this movie and I don’t have a spare second of brain power. I don’t have expectations of how the book is going to do. There is almost two hundred pages of material that we cut. “The Organist,” which is everyone’s favorite story, is not actually in the book. It was so huge and I was not going to finish it in time to get the book out when they wanted it out. “The Organist” can probably be a stand alone book. If somebody wants to pay money for it and some other stories, that would be great, and if they don’t, I might kickstart it. I have so many Lovelace and Babbage stories I want to draw. I’ve got a ton of gags and stories I want to do. It’s been killing me that I’ve been so slammed that I haven’t been able to keep the blog going. I’m sorry everybody! I’ve just had no time. When stuff slows down, I really want to start drawing again.

Dueben: But there will be more “Lovelace and Babbage?”

Padua: Yes!

Dueben: In your trip to America is there anything you’re really looking forward to?

Padua: Yes they’re going to have a very special private cranking of Babbage’s difference engine at the computer history museum for me. Which is so fantastic because they don’t run the one at the science museum here. It’s in a glass case, which is a shame. The thing about those engines is that they jam. [laughs]

Dueben: Which is part of the machine’s genius, as they explained to Queen Victoria!

Padua: Yes! I have a feeling that it would take quite a bit of readjusting if they wanted to run it a lot. I’ve never actually seen one live in operation, so I’m super excited about that.

![978-0-307-90827-8[1] 2](https://www.comicsbeat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/978-0-307-90827-81-2.jpg)

![978-0-307-90827-8[1] 2](https://www.comicsbeat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/978-0-307-90827-81-2-231x300.jpg)