by Alex Dueben

by Alex Dueben

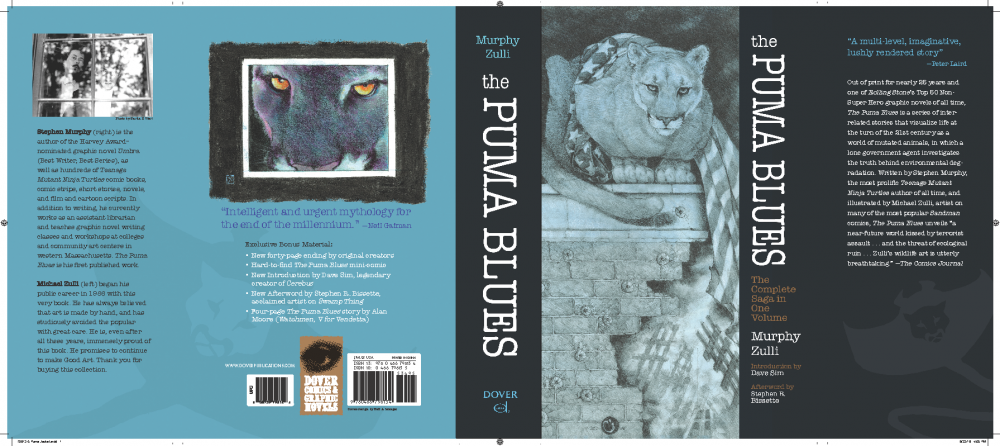

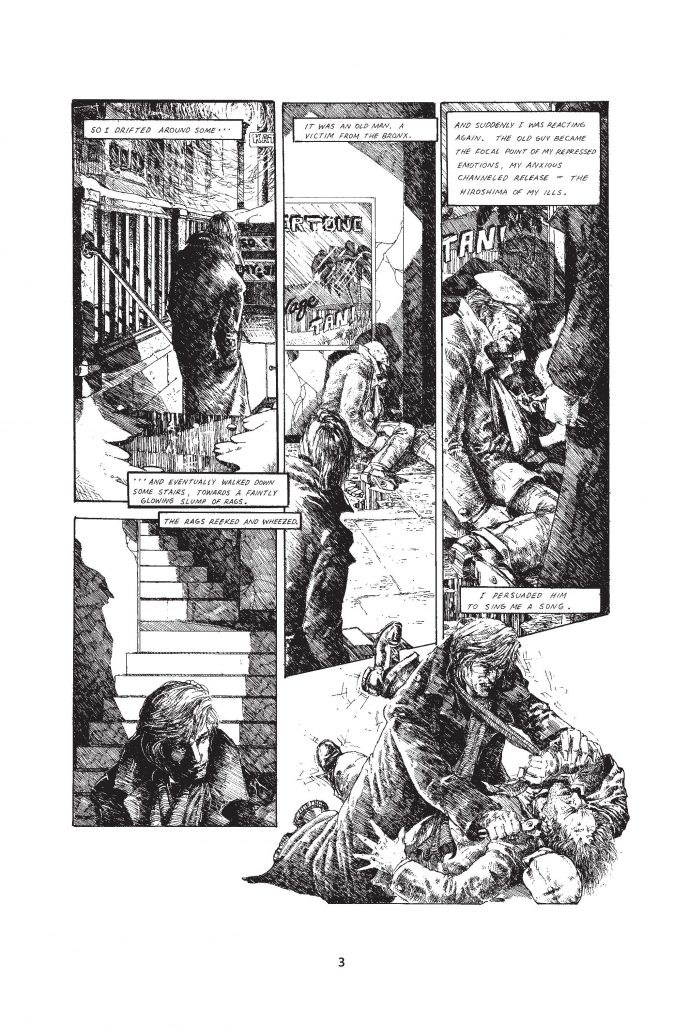

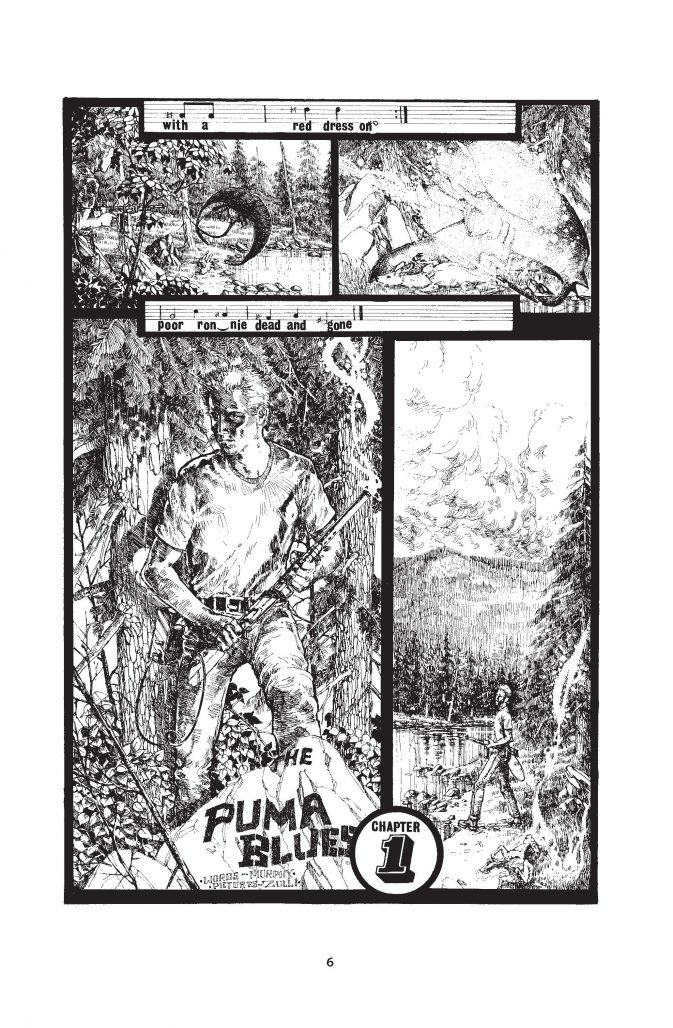

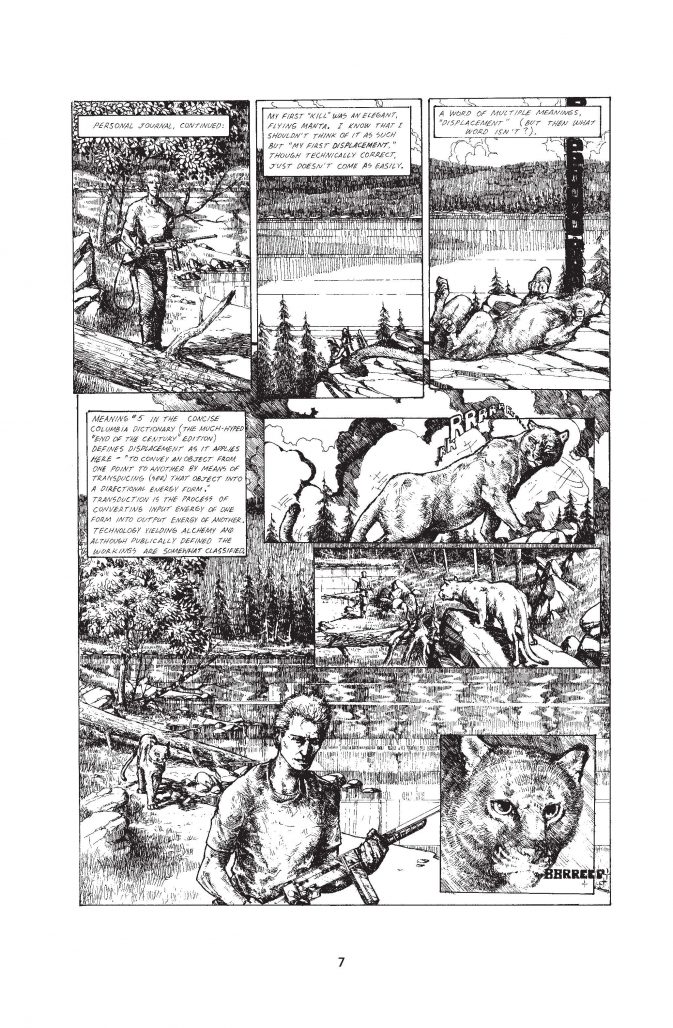

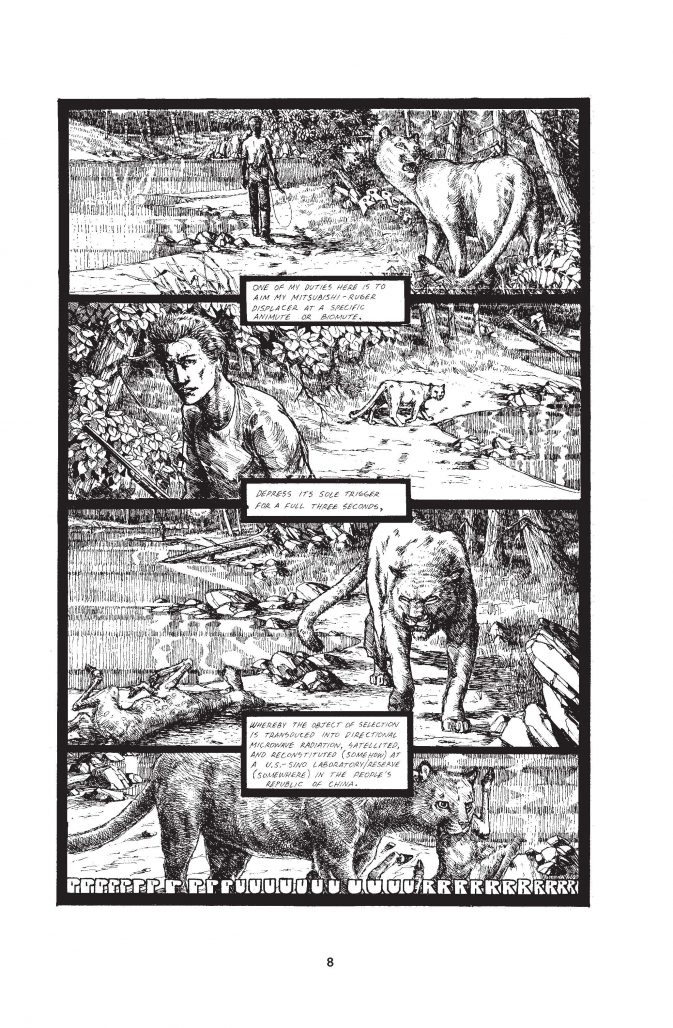

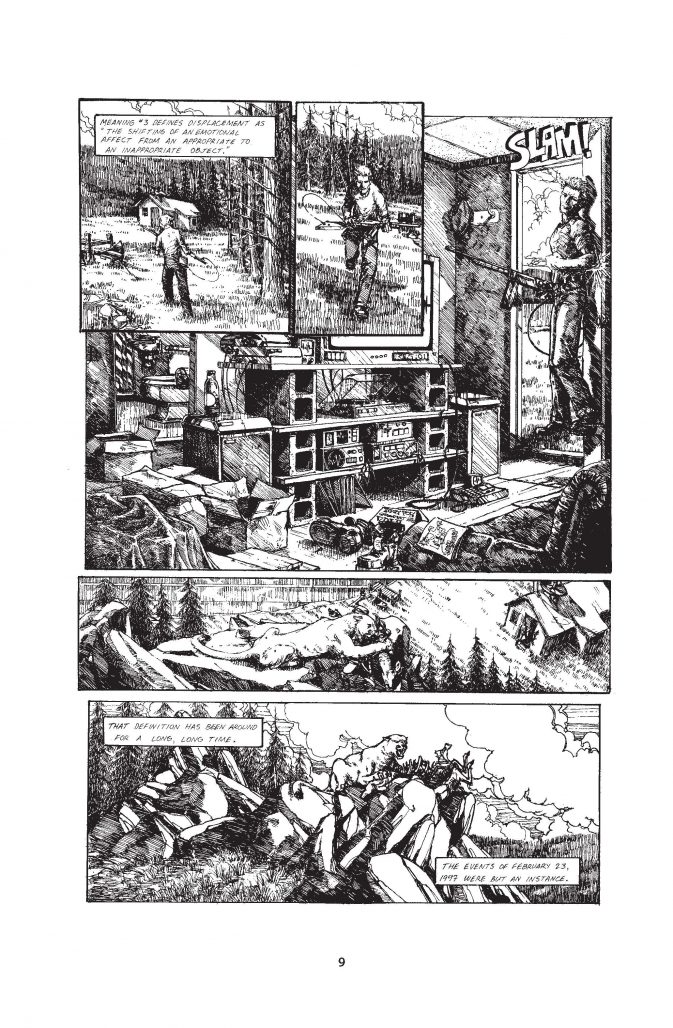

Stephen Murphy is best known for his long affiliation with the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, but many people still remember him for the series The Puma Blues that he created with Michael Zulli and ran for three years in the 1980’s. As someone who was too young to have read it when it first came out, reading the series for the first time last year was a revelatory experience. For someone who was so shaped and influenced by 1990s pop culture, Puma Blues was this missing link– a pop culture precursor to DC’s Vertigo Line, The X-Files, Twin Peaks and a thousand other creative works.

In 2015, Dover published The Puma Blues, collecting the entire series alongside a new epilogue created for the trade edition. In the epilogue, Murphy and Zulli pick up their story years later. Their main character Gavia is now older, living in Alaska, and dying. Murphy uses this chapter to comment on recent events in the world in a dark and wrenching finale that manages to be beautiful and hopeful in spite of its overall tone.

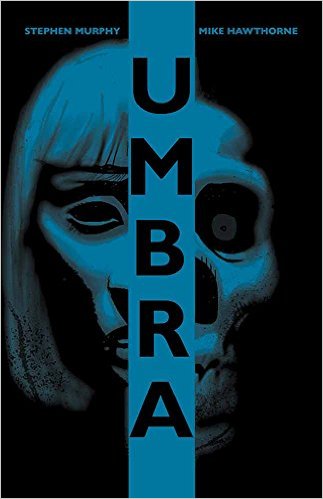

Recently, Stephen was kind enough to talk to the Comics Beat about The Puma Blues, his series Umbra, which will be collected next year, and related topics.

Alex Dueben: Where did the idea for The Puma Blues start?

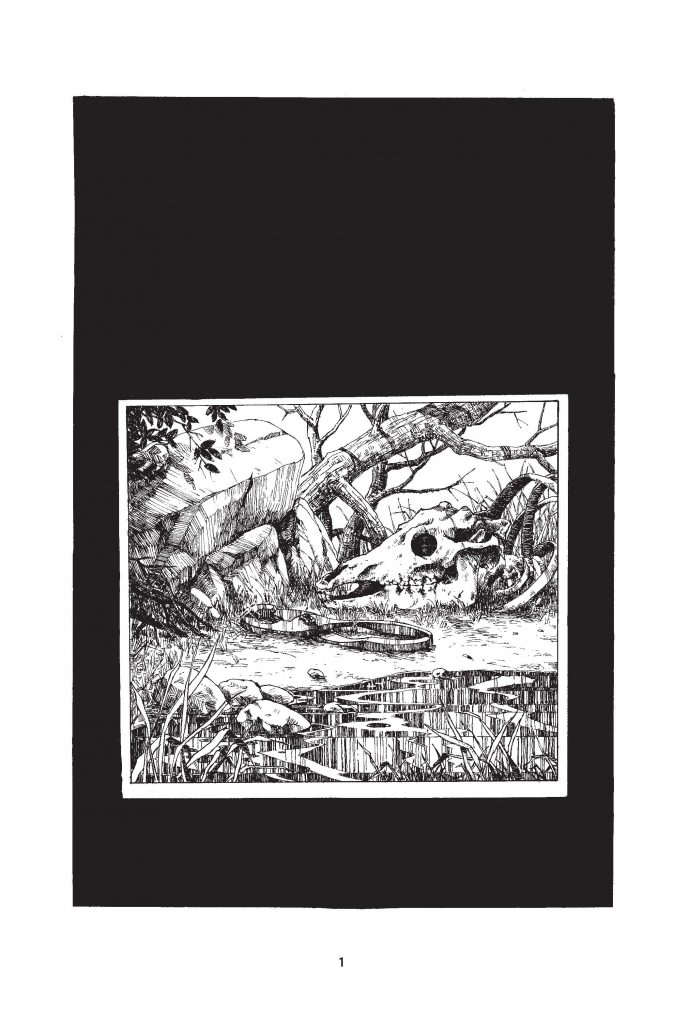

Stephen Murphy: When I was an underemployed twenty-something, I’d spend most of my free time hiking and bird watching in the Quabbin Reservoir of Massachusetts (it’s that huge v-shaped body of water in the west-central part of the state). Quabbin’s known as “the accidental wilderness” because it’s a young wilderness that developed after a handful of towns and villages were emptied out and physically dismantled to create a fresh water supply for the ever-increasing population of Boston. Animals returned to this area suddenly emptied of its human population, trees were given a chance to reach maturity, that sort of thing. At any rate, I spent a lot of time there by myself, thinking, keeping a journal.

At some point during that period, Jim Shooter, Marvel’s then-editor-in-chief, wrote an editorial asking for story submissions. I sent in two, and then received a short “close but not close enough” rejection from Shooter. Instead of taking that as a positive challenge I instead decided to come up with an original concept, met artist Michael Zulli while I worked at a comics shop, and the idea of Puma came to life. Pumas–mountain lions–continue to be rumored visitors to the Quabbin watershed. I’ve always wanted to see one but never have, whereas Puma protagonist Gavia Immer could care less, yet is sometimes shadowed by a puma. The first third of Puma is set at the Quabbin.

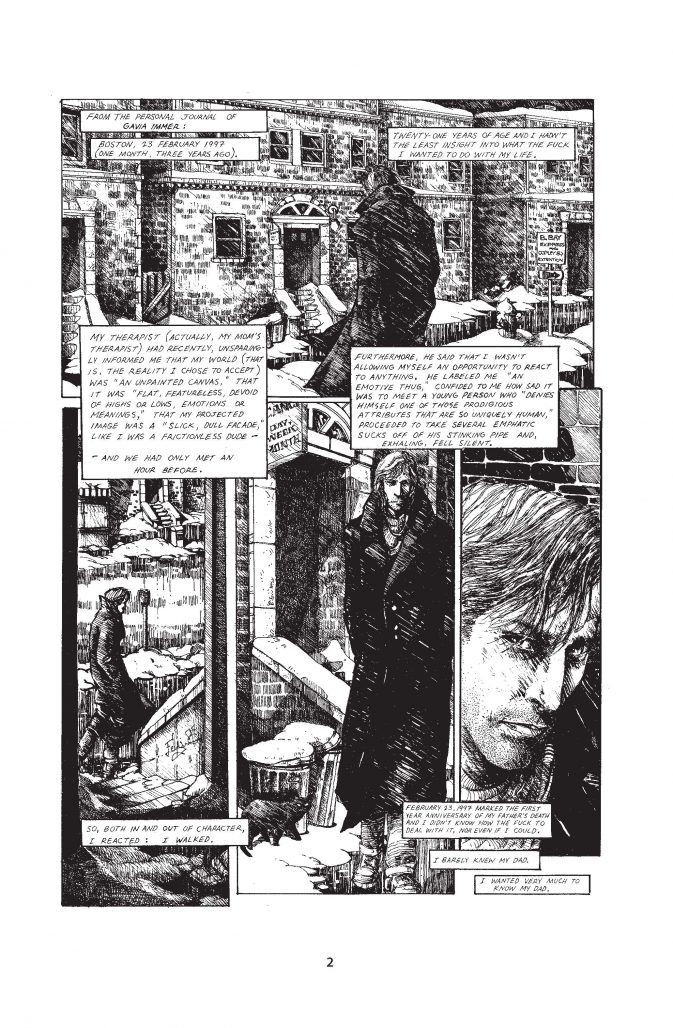

Dueben: Where did you come up with the name Gavia Immer?

Murphy: This too, goes back to bird watching in the Quabbin Reservoir. Every now and then I’d either hear or spot the Common Loon, and came to love its Latin name, gavia immer. Somewhere in the book’s early development I started thinking of the protagonist as being just about anyone, just an average guy, one of “usual gang of idiots.” In other words, just your average common loon.

Dueben: When you started working with Michael Zulli, how much did the idea change and evolve?

Murphy: Michael gave me the courage to openly express my strongest political beliefs in the course of our storytelling. Michael and I are cut from similar anarchist cloth–we saw (and continue to see) the world the same way–but I was afraid to fully express this viewpoint until I met Michael and learned that there was no reason not to be fully honest. In addition, Michael’s ability to stunningly capture wildlife in its purest most natural form, gave my imagination free reign when it came up to envisioning sequences with coyotes, eagles, and the like: I knew he’d be able to pull off anything that I’d throw at him. And he did.

Dueben: How much did his style and his work shape how you worked? For example there’s an early chapter, In the “Empire of the Senses,” which really stands out.

Murphy: Night. What happens at night in an island wilderness like the Quabbin? That was the starting point. The issue, like certain others, was an experiment with narrative. Could we answer that question while using wildlife and their various vocals as a means of telling a story? As a starting point I used an experience of mine where I’d snuck up on and scared a beaver, prompting the beaver to immediately slap its tail against the water surface in a loud clap in order to warn other beavers of my presence. I then wrote a script centered on the puma making its way through a very noisy night in the Quabbin watershed–an empire of the senses. If you’ve ever spent a night out in true wilderness, especially in spring, it can be really loud. That’s what we were trying to capture. It was the only time that I had a hand in the art, in that I helped Michael paste in all those various sound effects over the course of a very long afternoon. But it was fun.

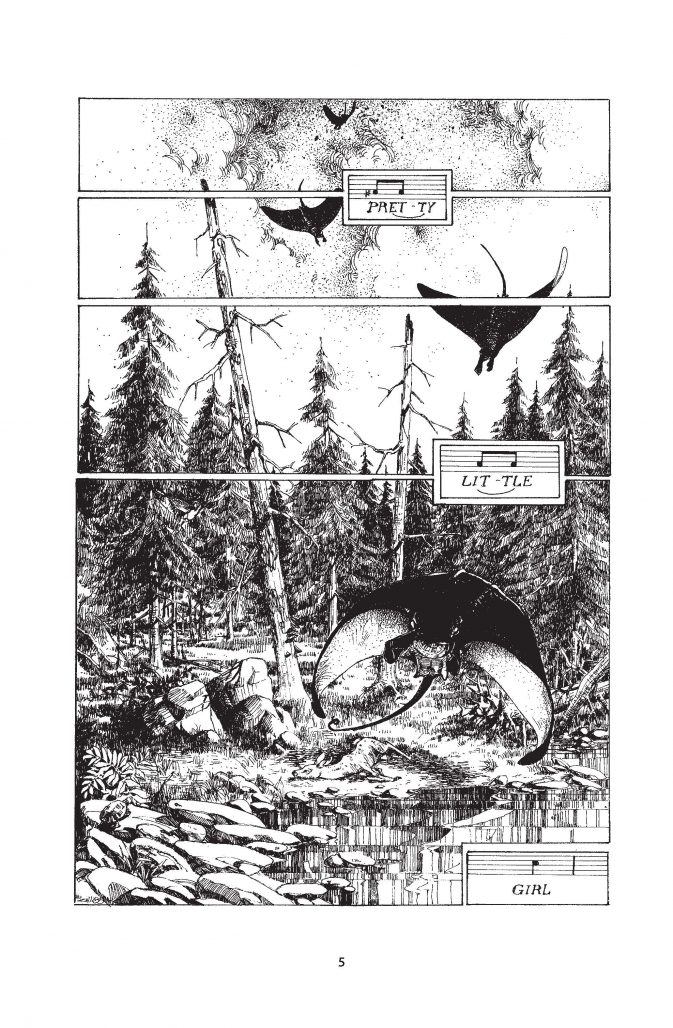

Dueben: Where did the idea of the flying mantas come from?

Murphy: I no longer remember the moment but the idea formed on one of my aimless hikes within the Quabbin watershed.

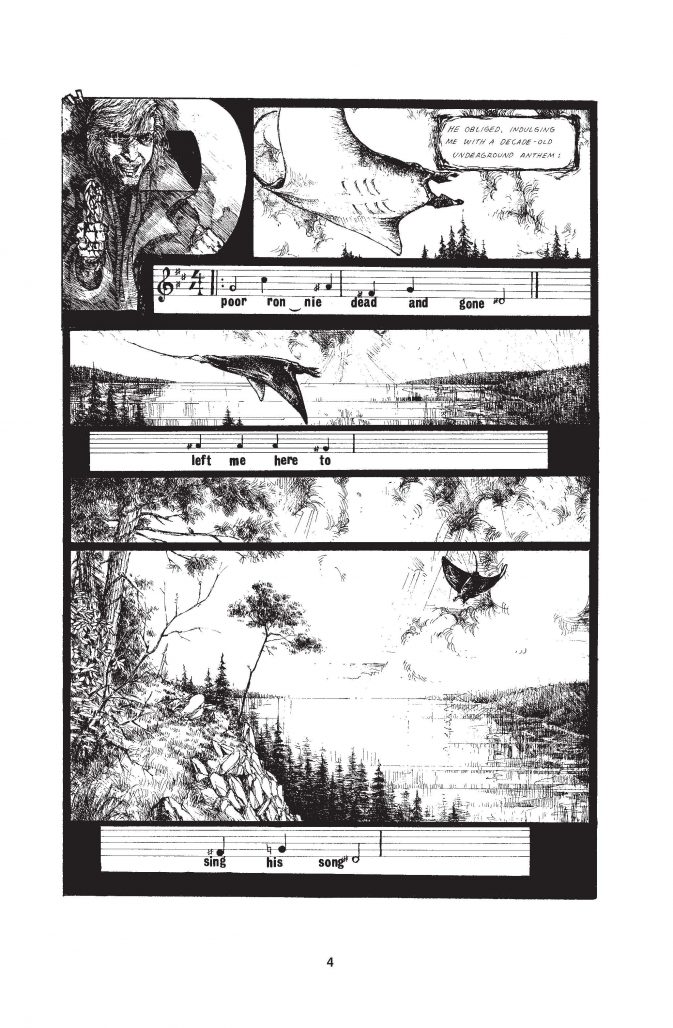

Dueben: There’s music running throughout the book in different ways and I wonder if you could talk about how you were trying to incorporate it.

Murphy: Some songs were used as a creative or inspirational starting point within the framework of whatever was happening in the story at a particular moment, the song acting not so much as a soundtrack or sonic background but in a sort of partnership with the story (both words and art/image); an attempt at putting the two together in order to create new meaning. Other songs–snippets of lyrics–are used to drive a point home. And still others are to create a mood.

Dueben: You were really interested in experimenting with the narrative and finding new ways to design and layout the pages. Michael said that that was really you, and I’m curious where that came from?

Murphy: Maybe from reading too much William Burroughs? Too many issues of RAW comics magazine? Perhaps it was from simply wanting and/or trying to be different, to challenge myself.

Dueben: Did you have an ending in mind for the book when you were working on it?

Murphy: No. Never had an ending in mind, never knew how long it would run. Not that I remember anyway.

Dueben: I never read The Puma Blues when it was first published, I only read it recently, but I was struck by how ahead of the curve you and the book were. So many of these ideas and concepts that you were playing with and addressing were at the heart of so many works in the 1990s.

Murphy: I felt the same way after re-reading the work prior to working up its ending. Well, I guess that’s a good thing, isn’t it?

Dueben: You mentioned that you were living in Western Massachusetts. How did you end up writing Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles? Because I know you did that for many years.

Murphy: Shortly after moving to Northampton MA, then home of Mirage Studios and the TMNT, Peter Laird invited me to share studio space with he and the other TMNT artists. Within a year or so my growing friendship with artist Ryan Brown resulted in his pushing me to try my hand at writing the Archie Turtles comic (floundering at the time with missed deadlines and editorial problems). So I did. And I found myself loving it. And Peter and Kevin (Eastman) were kind enough to offer me the regular monthly writing gig, which then morphed into a writer-editor (traffic manager, really) position. Over the years I was also presented with opportunities to write TMNT juvenile novels, action figure copy, cartoon episodes, and even a direct-to-DVD movie script that was never produced.

Dueben: Next year, Dover is releasing another book of yours, Umbra. What was Umbra?

Murphy: Umbra was a 3-issue series that came out via Image Comics in 2007 as one chapter of my ongoing working relationship with (current Deadpool) artist Mike Hawthorne. We’ve also worked on one issue of Mirage’s Tales of the TMNT, and we have an original graphic novel nearing completion. Umbra came about following a trip to Iceland that I’d taken a couple of years earlier; a dream I’d had upon my return, memories of some people I’d seen on the streets of Reykjavik, the island’s glaciers and hot springs. I had also finally made some progress dealing with life-long anxiety and occasional substance abuse–and somehow it all meshed together in a crime thriller. Here’s what the original Image press release stated: “Umbra is about a young police forensics technician with an anxiety disorder and a bit of a drinking problem, and how her discovery of a very strange skeleton sets in motion a series of violent and tragic events. And then things get weird.” Umbra received two Harvey Award nominations: best series and best writer. For this collection Mike and I have added 8 new pages in the middle of the last act, a little additional action sequence. Mike’s also done a new and very atmospheric cover.

Dueben: When Drew Ford at Dover came to you and Michael with the idea of collecting The Puma Blues, whose idea was it to make an epilogue and why did you say yes?

Murphy: Michael and I talked it over, then Michael laid some storytelling parameters on me: that the epilogue not be entirely pure comics/panels in format, that at least half of the pages be more prose than image. We then agreed on doing 24 pages of new material. However, I found that going from panels to prose etcetera was more difficult than I’d imagined. That is, I kept “seeing” the epilogue in terms of panels, of full comics pages. Deciding what to do as comics and what to do prose drove me nuts for weeks. I wound up writing most of it in comics, and then pulling out sequences to later turn into prose. The final script came in at 40 pages, not 24. Michael was gracious, which is why the epilogue is as long as it is.

Why did we say “yes?” We both felt that this would be the one opportunity to finally finishing our tale. Drew was behind us 100% too. The stars lined up and we ran with it.

Dueben: I ask because if the book ended where the original series ended, with him standing in the desert like that, obviously it didn’t wrap everything up, but I would have been satisfied with that as an ending.

Murphy: True. But we wouldn’t have been satisfied.

Dueben: The epilogue jumps ahead in time, and incorporates a lot of real life events. How do you go about thinking about making a way to wrap the series up? Especially after all this time!

Murphy: It wasn’t easy! I struggled with that ending over many weeks, first writing a script that continued the events of the last issue, just picking up where we left off, but I wasn’t happy with it, it just didn’t seem genuine. Then one day it struck me that I could once again have Gavia’s life mirror my own: both of us having aged, both of us having been struck with a debilitating illness and chronic pain (in my case, fibromyalgia; in his, something of unknown cause but similar to fibro, brought on by one of more of the weird things of his past, maybe the radiation given off by a gun that dematerialized mantas, maybe his visit to the Nevada Nuclear Test Site, maybe a bit of both). Once I had that anchor, things fell into place. Sad to say it was only too easy extrapolating today’s horrors along their collective one-way path towards even more horrific future events. Gavia can only watch, frozen in pain, shuffling forward through his functional depression, isolated, alienated, deeply in love with a beautiful but dying world.

Dueben: Like I said, there’s so much in Puma Blues that I recognized from other works ranging from The X-Files to The Invisibles. As you were writing the epilogue, jumping ahead in time, were you thinking about how these ideas has spread around and responding to that, or were you more trying to respond to the present and extrapolate from there, much the way you did with the initial series?

Murphy: The latter. Simply trying to extrapolate from here based on the status of things as they are today (environmental and species collapse, shortages in natural resources, politics, etc.), and hoping I’m wrong.

Dueben: Why do you have Gavia in Alaska in the epilogue?

Murphy: “North to the future,” the Alaskan state motto, had a bit to do with it. I see Alaska as a place Gavia would retreat to, (seemingly) far from the chaos and spiraling madness to the south, a place from which to watch in relative safety. Plus, as right wing as the state often is, there’s no denying the individual freedom found there. I saw that as appealing to Gav, as it does to me.

Dueben: David Bowie’s music is throughout the book, but he makes a very haunting appearance in the epilogue. With him dying a few months after it was published, now it’s haunting in a way you obviously never considered.

Murphy: It’s strange but I’d never imagined Bowie dying, ever. Creating music into one’s old age and while undergoing the agonies of cancer treatment–well, what a lesson for us all, what a gift.

Dueben: It is a rough ending. I mean this was never a deeply optimistic book but it was a very dark ending with a sliver of hope. Does that change reflect yours and Michael’s changing perspectives?

Murphy: I can only speak for myself here. I have an eleven-year old daughter. I would love to believe that there’s a sliver of hope for her generation. Mind you, I don’t think that the world is going to end. But I do believe that we’re in the midst of a sixth planet-wide extinction event, one that’s going to wipe out a high percentage of species–an event currently underway–and that a large portion of humanity will die off as well. The signs, statistics and facts surround us.

By the way, those last two story pages are pure Michael. My script ended with Gavia’s reincarnation elsewhere in the universe as an individual of a sentient alien species. Reincarnation as a universal concept. Life goes on via systems beyond our control or understanding in a universe also beyond our control or understanding. Michael, by showing a group of young “zoo disc” people paying respect to Gavia, adds a moment of warmth and humanity… and hope. (This is purely my interpretation of those two pages.)

Dueben: I was reading another book last week and I came across this line from Richard Nelson about the Koyukon people in Alaska: “Traditional Koyukon people live in a world that watches, in a forest of eyes. A person moving through nature—however wild, remote, even desolate the place may be—is never truly alone. The surroundings are aware, sensate, personified. They feel. They can be offended. And they must, at every moment, be treated with proper respect. All things in nature have a special kind of life, something unknown to contemporary Euro-Americans.” I don’t know if you know this and you meant for it to echo in your ending, or if this is a strange coincidence. Assuming you believe in coincidence.

Murphy: It is a wonderful coincidence, Alex. (I do believe in moments of more-than-coincidence. I just can’t explain such phenomenon.) The Koyukon worldview, it’s one that I’ve tasted here and there over the years–in Quabbin, Alaska, Iceland, the outermost dunes of Cape Cod–and one that I always try to remember (although I don’t always do). It would be cliché of me to say that the world would be a far different place if more people could experience and integrate into themselves a view of the world similar to that of the Koyukon. Thanks for sharing that with me.

Dueben: How does it feel seeing the series collected in one volume like this?

Murphy: Humbled, awed. Heck, I almost cried the first time seeing it. Editor Drew Ford and Dover’s production department (along with my graphic design partner, Mark Masztal) gave it a beauty of form that complemented the gorgeous art within. Plus, well, it kind of floored me seeing just how much Puma material that I’d written. I honestly feel that I had no idea just how long (and, yes, sprawling) it was. And it made me less dismissive of my early work. I hadn’t read it in over twenty years and was amazed revisiting those moments–mostly forgotten over the years–when I’d fully connected from brain to page.

Dueben: Do you have other books you want to make, that you want to write?

Murphy: I do. I’ve got two original graphic novels that need (mostly) production completion: the aforementioned one with Mike Hawthorne (autobiographical), and another with artist Dario Brizuela (existential Vatican crime thriller). I’ve several stand-alone graphic novel scripts that I’ve never shown around but ought to, and I’m currently 4-issues in on a tightly plotted 18-issue adventure series set in the back woods and related shadows of America. While I like the “one-off” nature of the graphic novel, I love the 24-pages per month format of the typical comic book series – it’s what I grew up on. After that I’ve another “finite” series idea to complete. I just need to find some artists to partner up with.

Meaty interview.

– “those last two story pages are pure Michael”

That’s so great he went beyond the call of duty, not just in consenting to 40 pages instead of 24, but also in contributing this coda. I guess he bounced off your “Nine billion Judases” by depicting Gavia and his journal as an ecological Jesus.

– “Gavia’s reincarnation elsewhere in the universe as an individual of a sentient alien species”

Cool, I couldn’t convince someone the ending went 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY!

– The book can be seen as a graphic elegy, an experimental poem not unlike KOYAANISQATSI, but would that preclude some base questions?

* Did the transducer always work or was it destroying mantas? Is that why Gavia says he’s happy to have failed at killing them off? Why didn’t transducing revolutionize transportation?

* Did Ernest go and jump in the lake?

* Did the ear-crushing scene originate in something specific?

* Did “Zoo Disc” refer to “disc”, “disciple”, “discipline”?

* Did “Zanzibar” refer to John Brunner’s classic STAND ON ZANZIBAR?

* Did the alien Horsemen refer in part to Galactus?

– Thanks for THE PUMA BLUES, and for all those it inspired.

I grew up in the Amherst/Northampton area, and the Puma Blues was part of my teenage years. They’d come out and be a part of local Mirage signings (at Moondance Comics, among other places) so I met both Zulli and Murphy several times. I love that they were able to finish this story, which haunted me then and continues to haunt me now.

I would love to know what the original ending was going to be. In reading what was published in the collection it seems unlikely that was the original intention back in the 80s. I also have memories of Murphy telling me that his outline (at the time) had the story ending roughly at issue 36 or so.

Comments are closed.