The concept of fake news existed long before Trump, and conspiracy theorists have also, but one difference between now and even a decade ago is that the institutionalization of misinformation has exploded and brought it more into the mainstream. Seth Rich conspiracy theorists, Pizzagate advocates , 9-11 truthers, Obama truthers, and the nearly-constant chant of “crisis actors” at mass shooting help create an atmosphere of unreality, abetted by online togetherness and targeted media manufacturing pocket universes of intensity that fuel these delusions.

The truth is that all of us live in our own pocket universe, featuring emotion as our physics. Communities built around conspiracies wrap themselves parasitically around these bubbles of ours, feeding on them like a tick and then inserting a debilitating bacteria that clouds all reason.

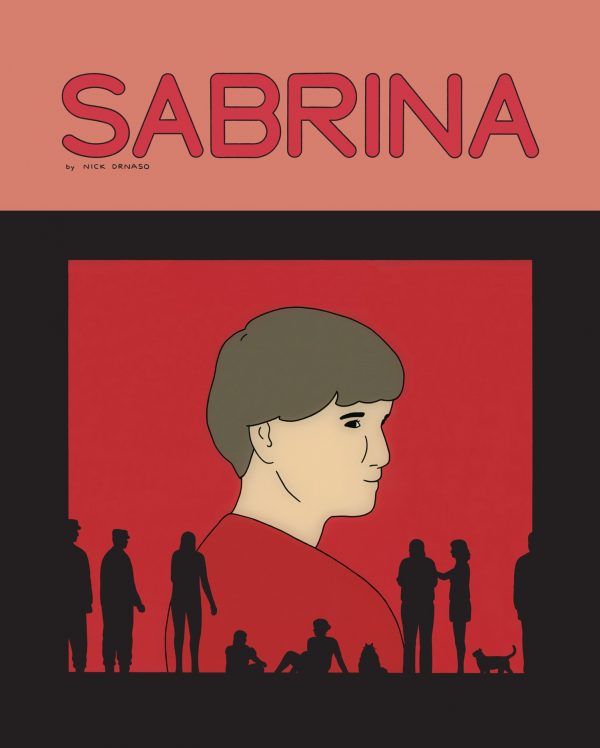

All of this brings us to Sabrina by Nick Drnaso, which examines the dynamic I’ve just described, on a devastating and artful level while maintaining the cloudy aspects that make it so scary. This distance in Drnaso’s presentation heightens our own sense of foreboding and paranoia and suggests that their physical existence may not be as potent as their ability to infect the atmosphere we exist within. They seep into our personal bubble universes, poisoning the air just enough to send us into a permanent state of unease.

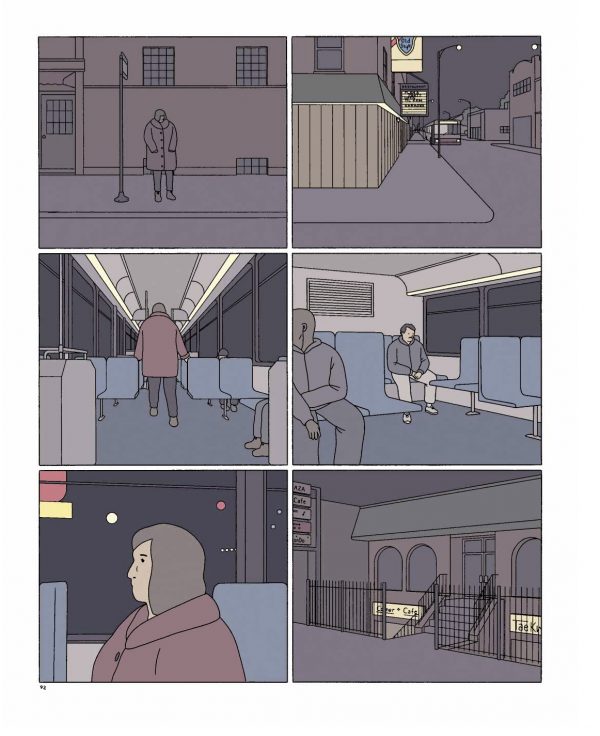

Drnaso’s story unfolds within these pockets which we piece together much in the way a conspiracy theorist might connect dots in news reports. Instead of wide-reaching news stories Drnaso presents us with intimate scenes, some mundane, that we have to string together into some sort of linear dramatic sense. That linear quality is already there, but trapped in an atmospheric cloud that makes each quiet moment awkward and suspect, as if living in a heightened version real life where something we can’t quite put a finger on what has been tweaked.

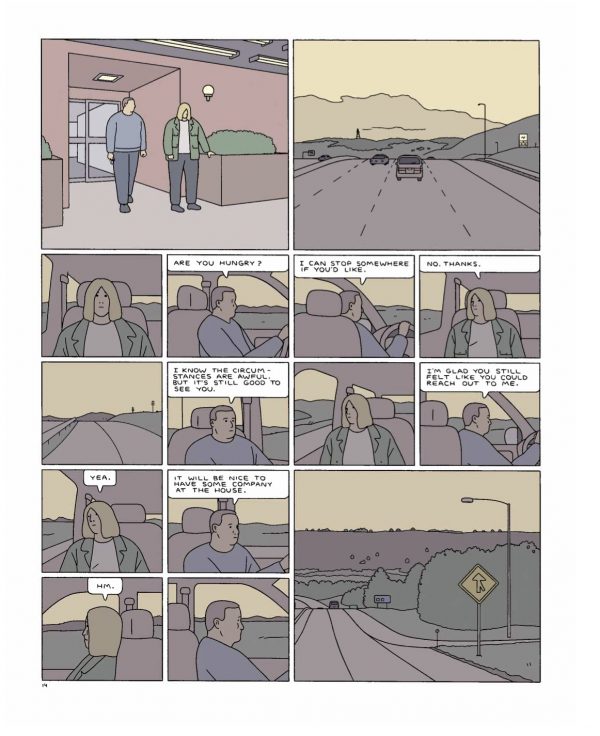

I hesitate to give too many narrative details, not because of fear of spoilers, but because each turn of plot alters the emotional course of the characters and also the wider scope of what Drnaso is examining, and these benefit from the lack of a road map. At its narrative root Sabrina concerns the disappearance of a woman and the toll it takes on her sister, Sandra, who descends into depression and anger, and Teddy, her boyfriend, who functions mostly as a shell of a person, unsure how to cope with his reality.

But it’s actually an unrelated person who is the story’s largest focus — Calvin Wrobel, the friend who Teddy flees to. Calvin takes Teddy into his home and helps him through his struggle with a calm demeanor that at first seems like a strength, but in reality might just be a numbness born of his own problems. Calvin is in the military, separated from his wife and child, and trying to figure out whether he wants to continue with his career, or not re-enlist and attempt to heal his relationships.

But the missing woman begins to further affect Calvin thanks to his personal interaction with Teddy, but also events that draw him into the public narrative. He attempts to handle these circumstances, but finds with each attempt that he has no control over the story as it unfolds. He’s just a character beholden to the whims of a multitude of authors outside his bubble and his only hope might be to reject that wider story and seize control of his own, even as they meld with the doubts he has about his own job.

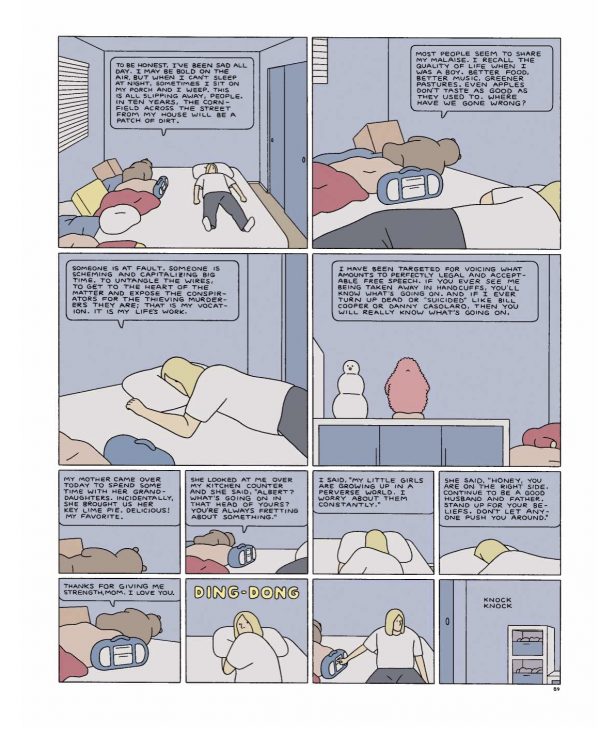

There is a series of scenes with a conspiratorial radio show host that drive home many of the themes being explored here. It suggests that those on the conspiratorial side are no different than anyone else. They are reaching out to other humans with their fears. They are trying to explain what the hell is going on around them. They are trying to feel safe. As Drnaso presents the people on the receiving end of the conspiracy, it’s not hard, especially thanks to the radio scenes, to imagine those on the other side, no less human, no less tortured than the characters this graphic novel.

There is something otherworldly about Drnaso’s comics. Partly its the distorted human beings with their wide bodies and round heads inhabiting a cleanly-rendered universe. Partly it’s the silence that steers so many of his panels and the awkwardness that unfolds when dialogues begin. In Sabrina, the presentation combines well with the themes, creating a multi-layered mood piece with a cinematic feel.

This is a story of the desire for connection and truth crashing and burning. It’s an immensely sad story that will haunt you. And like all good conspiracies, the psychological unreality it portrays eventually become so heightened and intense that it begins to feel far too real, and you won’t know the difference anymore because it has infected you.

Looks great. Appreciate the non-spoilery review.

Comments are closed.