In case you missed the first portion of this special two-parter, it was revealed that Batman has conquered America and has established his black Bat-capital in a cave in Branson, Missouri.

That is not entirely true, but I do hope something of the story in the Bald Knobbers (cringey name aside) rang true for Batman fans. The vigilante story is old and real in America.

But is it enough to explain Batman’s popularity? We know many possible fictive sources for Batman – detective stories, operas, and movies – but what about other real ones?

There are a few possibilities. Both Bob Kane and Bill Finger, the co-creators of Batman, probably attended the 1939 New York World’s Fair. One of the Fair’s regular attractions was the skydiving “Bat-man”:

There were many “Bat-Men” who jumped all over the country. They were so popular that Major Malcolm Wheeler Nicholson (who basically invented comic books), urged America to “consider the possibility of bat-man troops!” in a 1941 article.

But this might just be distraction, like billowing smoke from a Bat-capsule. We don’t really go to air shows that much anymore, after all. Is it Batman’s design motif? The vampire bat doesn’t even crack the top 25 of National Geographic Kids’ most popular animals. Certainly the car and Kevlar help, but you can’t last 75 years with just a black cape and pointy ears.

Batman’s creators might help provide answers. You probably know Batman’s artistic origin already, but the general public may not, so we have to keep repeating it. Bob Kane was a fledgling New York artist supposedly jealous of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the two creators of Superman. Kane pleaded to editor Vin Sullivan, who gave him a weekend to create a new superhero.

Kane needed help, so he approached Bill Finger, a former shoe salesman whom he had worked with previously on some Western comics. The result of their new collaboration was Batman’s first appearance in Detective Comics #27 in 1939. Finger wrote the script and Kane drew the action. Kane got the byline. How and why this happened is not fully known. Kane was a hustler and Finger was meek, though there was probably more to it than that. After all, most of this story, if not all of it, was first told by storytellers.

In that first issue, Kane swiped liberally from Henry Vallely and copied poses from “Flash Gordon.” Finger’s first script was probably inspired by pulp stories like “The Black Bat,” movies like “The Bat Whispers,” and a Shadow story. Superman had been crafted over several years and was something really brand-new. Batman was a smoky concoction of vigilante stuff thrown together to create a quick, commercial superhero.

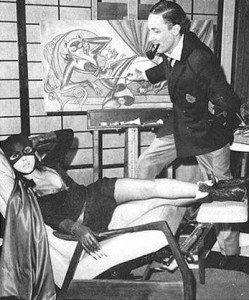

Finger worked on Batman comics, including the first telling of the origin, in complete anonymity for decades. Kane drew only sporadically and wore ascots to parties. Finger is acknowledged by many as being responsible for some of the major chess pieces of the mythos. Kane appeared on The Tonight Show and died rich at 84. Finger died poor and alone at 59. This year, Kane is going to receive a posthumous star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

As a consequence, fandom has not been kind to Bob Kane. Any mention of him at a Comic-Con panel usually results in some story about him stiffing a dinner bill forty years ago or bragging about supposedly dating Marilyn Monroe. In his autobiography, Kane even waxes breathlessly about fighting a gang as he swung around a lumberyard. Kane also claimed to have drawn the monthly Batman comic for decades when he positively did not. And he didn’t publicly recognize Finger’s contributions to Batman until after Finger was dead.

Still, there is no question that Bob Kane is the co-creator of Batman. He drew the first appearance of the character. For comics – which are words combined with images – that is half the whole world.

Still, Kane (and to some extent DC’s) treatment of Finger is considered by many to be wrong, even criminal. It is well-documented and crusaded upon, as it should be. But I am interested in crime of a different sort here.

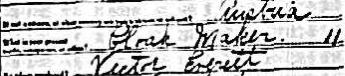

Bill Finger’s early days have been mostly lost to time. Born in Colorado in 1914, Finger grew up with his immigrant parents and a sister. His father Louis, according to his World War I draft card, was a “cloak-maker.”

Bob Kane was born Robert Kahn in 1915. When he was born, his parents ran a candy store in New York City. His father later worked for the Daily News as a typesetter.

Both Kane and Finger grew up on the Grand Concourse, a nearly five-mile stretch in the Bronx. They stared up at art deco buildings and gargoyles.

They were not friends as kids. But they both saw bad things. Real things.

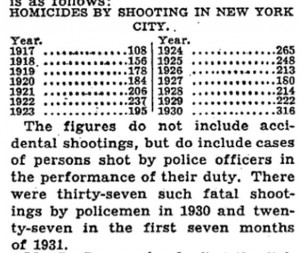

Crime in New York City during the twenties and thirties was on an escalating slope. On August 1, 1931, the New York Times ran a table titled “Homicides by Shooting.” In fifteen years, the number of murders in New York City tripled from 108 to 316. By 1939 – Batman’s debut – the rate had reached nearly two murders a day.

Every day, the papers were a blotter of theft and murder. Gangsters, passerby, and children were robbed and killed in streets and doorways. In April of 1939, the papers reported the tragic story of a brother and sister coming home from the movies to find their parents shot dead on the floor.

People lived in sadness and fear. It eventually turned to anger. When five children were struck down by stray bullets in the Bronx in 1931, Police Commissioner Mulrooney vowed that “We’re going to meet force with force…If they want war, we’ll give it to them.” Several articles urge the formation of “vigilante committees” to enforce the law themselves.

This is where Batman began.

In late 1937, when Kane was just breaking in and earning around $25 a week. A small article appeared in the November 28, 1937 issue of the Times titled “Woman, 75, Killed in Street.” It read:

Mrs. Augusta Kahn, 75 years old, of 1,160 Grant Avenue, the Bronx, was fatally injured shortly after 5 P.M. yesterday while crossing Broadway at 115th Street. She died on her way to Columbus Hospital . . . Alexander Novinsky, 26 years old, of 6,802 Nineteenth Avenue, Brooklyn. Novinsky was held on a technical charge of homicide.

Bob Kane’s mother was named Augusta Kahn.

But this wasn’t her. It was a different woman. It was someone else – a double somehow– who was very real. Was Kane even aware of the story? Who knows, though someone surely must have noticed it in the paper and told the family. Kane was living with his parents at the time. If he did know of it, it must have provoked a visceral response. Especially because of what would happen next:

Alexander Novinsky, 27 years old . . . arrested Nov. 28, last when an automobile he was driving struck and killed Mrs. Augusta Kahn . . . was discharged yesterday by Magistrate Edgar Bromberger in Homicide Court for lack of evidence tending to show culpability.

The driver who killed the other Augusta Kahn — someone else’s mother — went unpunished. Novinsky walked scot-free. Was it an accident, or something else? The courts ruled that there was not enough evidence to pursue it.

Just as forty unpunished murders provoked a solider to don a mask in the Ozarks, so might crime in the Bronx have inspired a fictional character to do the same. The cowl, the cape, the symbol and all the pulp stories and films that inspired the look of Batman — is a smokescreen. Crime is why it stuck.

I think that much of what we claim to like about Batman is a complete cop-out. The most common explanation of the character’s popularity is his “humanity.” What that usually means is that anyone – if they had enough money, ninja training in Nepal, gadgets, and a sidekick – could be Batman. But none of us really believes that. Batman is not real, even though we constantly act like he is. The only thing real about him is his genesis in crime, whether it is a story in a comic or the story of his creators.

When James Holmes killed twelve people at a midnight screening of The Dark Knight Rises on July 20, 2012, the press made connections to the killer being inspired by the Joker. Most of this has since been dismissed, but it speaks volumes that this explanation was the first one that made any kind of sense to the general public. Not that Holmes was clearly psychotic and a killer, but that our response to him, at first, involved Batman. When Holmes first appeared in court several days after the shooting, survivors of the massacre showed up to the courtroom wearing Batman t-shirts.

The current writer of the monthly Batman comic, Scott Snyder (who also teaches creative writing at Sarah Lawrence College) has a theory about Batman that might help. In Batman #27 (note the number), Snyder (alongside collaborator Greg Capullo on art) has Alfred dramatically assess Bruce Wayne’s mission:

You keep us all around to bear witness, to see that you can do the thing that none of us could do for you. That none of us were there in the alley that night, not Gordon, not me, not anyone in this city. And you’re out to punish us for that every night.

What Batman has made us watch for seventy-five years – an epoch in pop culture – is a one-man war that most of us don’t know how to fight. Batman isn’t about hope; it’s about fighting back against things bigger than us — crime, characters, and the Batkid’s cancer. It is not a place of light or peace or even nobility. It is a street in a city. Most of us can’t jump around on rooftops. But we can imagine that action — that rebellion — when we wear the black t-shirt. That we can do.

Batman is the most popular superhero in America because we all want to hit something sometimes. This applies to fandom as well. Sometimes it can be fairly vacant — Affleck, nipples — but sometimes it is more important. When Batman character The Spoiler, a teenage girl, was killed in the comics, fans began protesting the lack of a memorial to her in the comics’ Batcave. Marc Tyler Nobleman (with Ty Templeton) produced a book about Finger and led a massive campaign to get a Google Doodle to honor the writer. Filmmaker Kevin Smith (who has built an empire around a Batman podcast) also helps to run The Wayne Foundation, a non-profit group dedicated to help stop the sexual traffic of children. Finger documentaries are being funded, Glen Weldon has a cool new book on the horizon, a new Batgirl is making waves, and for the first time, Bill Finger’s name was credited on a Batman comic. That last one has a simple explanation.

What matters is that these endeavors – all of them real – are small vigilante acts done in the name of Batman. It is not the fictional character or the dead men we rally around, it is that central story in Crime Alley. That’s the one that gets us. That’s the one that inspires us to do things, try to help, or just like Batman. That is where the humanity — and popularity — of Batman really lies: in the detective and the crusader, not the pull-ups in a cave.

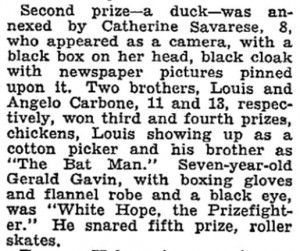

On November 24 of 1939, just a few months after Batman’s debut, the winners of a kids costume contest were announced in the Times:

I won’t argue that “The Bat Man” is an infinitely better costume than “cotton picker” or “camera,” but Angelo Carbone didn’t just want to win a free chicken. With the exception of the boxer, all of the other costumes sound parent-selected. Not “The Bat Man.” Angelo saw something in a comic he liked and went for it. He saw something he needed to be.

As I write this in Cleveland, there was a break-in last night at the university I teach at. Three students – all studying – were robbed at gunpoint in the common room of their dorm. A few weeks ago, in the middle of a sunny day, young men walked into my favorite neighborhood bar, The Colony, and shot the owner, Jim Brennan, dead.

Why is Batman so popular? Look around you and read the news.

This is Batman Country. That should both empower and terrify us.

P.S.

Speaking of detectives: there is one last mystery to bring up.

In the late nineties, a story surfaced out of Boston suggesting that another artist may have created Batman well before Kane and Finger (and not Siegel and Shuster, as I’ve half-suggested before).

Frank D. Foster II was a cartoonist who worked with Al Capp in the thirties. When he couldn’t get regular work, he abandoned comics for a job at what would become the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

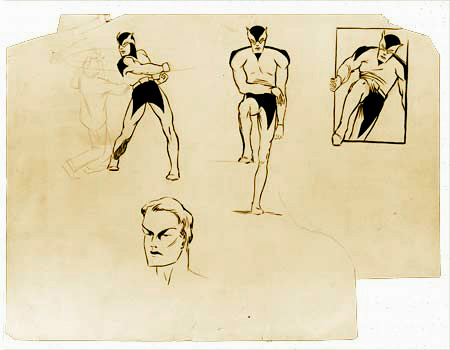

Supposedly, Foster had samples of a character named “Batman” that he shopped around New York before leaving for Washington — well before 1939. When Foster later saw fully-realized Batman comics in the forties, he was stunned — had they stolen his character? Foster and his family talked to an attorney in 1975, which was also when Siegel and Shuster’s plight was all over the news. After Foster died in 1995, his son Frank continued to ask questions. His website. OriginalBatman.com, reads: “Although there is no hard physical evidence, there is little room for doubt that people at DC saw the drawings. Most likely it was Bob Kane himself who was at DC at the time and claimed credit for creating Batman.”

The problem is that there were no superheroes in 1932. Not til Superman. And these sketches are definitely of a superhero – the bottom face also looks very much like a Bill Everett Sub-mariner (thanks to fellow Beat contributor Jeff Trexler for that). At one point, Foster places the drawing even earlier, in the twenties. None of this is impossible, of course, but if true, then Foster’s Batman would have been the first superhero.

There are other problems of dates and letters, but take a look for yourself. Foster’s 1975 interview with the lawyer provides fascinating insight into how artists worked back then. And how the fallibility of memory complicates everything.

Is there any way to prove that Kane and Finger saw Foster’s drawings? They never mentioned him. Or did they?

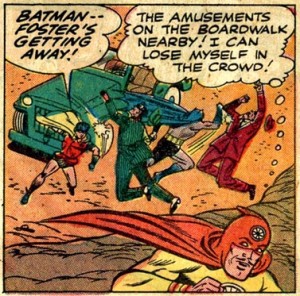

In 1960, when Batman was well-established, Bill Finger wrote a script for Batman #135 called “Crimes of the Wheel.” In the story, the Dynamic Duo breaks up a gambling den, sending its leader, a man nicknamed “Big Wheel” to jail. He escapes and puts on a bright costume that is a garish copy of Batman’s. Now a villain with who uses wheel gadgets, he calls himself “The Wheel” (hey, it’s still better than “Bald Knobbers”).

His ridiculous costume looks like a garish version of Batman’s. But he’s a moron and soon gets tossed back in jail. He gets made fun of — by other criminals, by Batman and Robin — for the entire issue. The character’s name who steals Batman’s shtick but fails? Frank Foster.

Is this pure coincidence or a hidden in-joke? On his website, Foster’s son says of the original drawings by his dad:

I know he created Batman. It’s the first Batman. It was there, at the same place, at the same time Batman was published. There has to be a connection. The possibility of two men in 5,000 years of history arriving at the same character who’s a hero of the night, with the same name of Batman, at the same time, at the same place on the earth, is zero.

I don’t know what to make of Foster, but I do know that the possibility is never zero when it comes to talking about comics and culture. If we think of Batman as a cape and cowl, then sure, but as the fictional embodiment of our own fear of crime and desire for vengeance? That is more universal than zero. Perhaps more than we’d like to admit.

If you’re at Comic-Con, come to “Who Created Batman?” on Fri. from 2:30-3:30 in Room 26AB for a panel with Travis Langley, Tom Andrae, Athena Finger, Marc Tyler Nobleman, Denny O’Neill, Jens Robinson, Arlen Schumer, Michael Uslan, Nicky Wheeler Nicholson, and myself. PW is calling it one of the 14 Best Panels at Comic-Con.

Brad Ricca is the author of Super Boys: The Amazing Adventures of Jerry Siegel & Joe Shuster – The Creators of Superman, now available in paperback. He also writes for StarWars.com. Visit www.super-boys.com and follow @BradJRicca.

As always with you, Brad, a sharply written piece with great research no one else has done. I have been asked about Frank Foster’s claims often enough that I posted my response: http://noblemania.blogspot.com.com/2012/04/batman-of-1932.html.

That link again, only correct: http://noblemania.blogspot.com/2012/04/batman-of-1932.html.

Comments are closed.