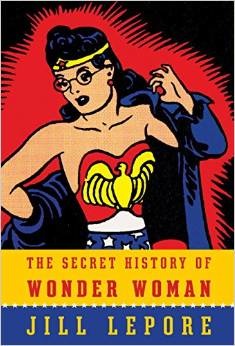

These are only a few of the historical facts uncovered by Harvard history professor Jill Lepore in her upcoming volume The Secret History of Wonder Woman. It turns out a lot of that history is very secret, but Lepore has gone through Marston’s hitherto unseen private papers, and correspondence from his wife, Sadie Elizabeth Holloway, and Olive Byrne, the third housemate, and niece of Sanger. Lepore is also a staff writer at The New Yorker and a few weeks back her article for that magazine laid out the bare bones of the story.

In 1917, when motion pictures were still a novelty and the United States had only just entered the First World War, Sanger starred in a silent film called “Birth Control”; it was banned. A century of warfare, feminism, and cinema later, superhero movies—adaptations and updates of mid-twentieth-century comic books whose plots revolve around anxieties about mad scientists, organized crime, tyrannical super-states, alien invaders, misunderstood mutants, and world-ending weapons—are the super-blockbusters of the last superpower left standing. No one knows how Wonder Woman will fare onscreen: there’s hardly ever been a big-budget superhero movie starring a female superhero. But more of the mystery lies in the fact that Wonder Woman’s origins have been, for so long, so unknown. It isn’t only that Wonder Woman’s backstory is taken from feminist utopian fiction. It’s that, in creating Wonder Woman, William Moulton Marston was profoundly influenced by early-twentieth-century suffragists, feminists, and birth-control advocates and that, shockingly, Wonder Woman was inspired by Margaret Sanger, who, hidden from the world, was a member of Marston’s family.

This week, there’s a piece Lepore has written for The Smithsonian with much of the same material but some new stuff too, such as the role of Dr. Lauretta Bender a psychiatrist who was something of the anti-Wertham:

Gaines decided he needed another expert. He turned to Lauretta Bender, an associate professor of psychiatry at New York University’s medical school and a senior psychiatrist at Bellevue Hospital, where she was director of the children’s ward, an expert on aggression. She’d long been interested in comics but her interest had grown in 1940, after her husband, Paul Schilder, was killed by a car while walking home from visiting Bender and their 8-day-old daughter in the hospital. Bender, left with three children under the age of 3, soon became painfully interested in studying how children cope with trauma. In 1940, she conducted a study with Reginald Lourie, a medical resident under her supervision, investigating the effect of comics on four children brought to Bellevue Hospital for behavioral problems. Tessie, 12, had witnessed her father, a convicted murderer, kill himself. She insisted on calling herself Shiera, after a comic-book girl who is always rescued at the last minute by the Flash. Kenneth, 11, had been raped. He was frantic unless medicated or “wearing a Superman cape.” He felt safe in it—he could fly away if he wanted to—and “he felt that the cape protected him from an assault.” Bender and Lourie concluded the comic books were “the folklore of this age,” and worked, culturally, the same way fables and fairy tales did.

With Wonder Woman finally getting a crack at being a big time character again, I’m sure all of this secret history will be sifted for evidence pro or con, and will add to the “complicated” nature of the character. I expect anyone who gets the Wonder Woman writing should probably read this book cover to cover…and so should anyone interested in the history of one of the great superheroes.

So excited for this!

I’ve read both the articles, and they’re great. Definitely looking forward to the rest of the book.

I’m also very excited to read this book, but as someone with a Masters Degree in English (and an undergraduate degree with a minor in Critical Writing), I must admit that I’m going to approach this book with optimistic caution. Simply put, until I read it, I can’t judge the merits of her scholarship, and I must admit that I’m concerned about whether this has been peer reviewed at any level. Until I know the answers to those questions, I’m concerned about headlines like the one on this article: “This fall we learn the truth about Wonder Woman.” Is it truth, or biased feminist opinion? One of the big flags for me is the way it attempts to tie Wonder Woman to the founder of Planned Parenthood. This could be true — I don’t know yet — but when I read something like this, my academic warning lights flash a red alert that this may be an attempt to co-opt Wonder Woman to an agenda to which her creator (and early author) did not intend. I suppose I’ll be more blunt here: For many years, some feminist scholars have lumped Wonder Woman into the “body loathing myth” with Barbie and Supermodels. Is tying her to an early icon of modern feminism (the founder of Planned Parenthood) true, or is it just an attempt to counter those critics?

I don’t know.

I hope the book is great, but as this claims to be a work of scholarship (even if it is written in a populist manner), I hope everyone reading it will do so with a critical eye toward any agendas, hidden or overt.

While you are waiting on this, you can check out this comic I wrote about Marston’s life! http://www.comicfleamarket.com/servlet/the-404/Female-Force-cln–William-M./Detail

I feel your pain, Mike. Some months ago I was thumbing through a bookstore copy of an academic book about Wonder Woman, wondering if I should give it a chance. The moment the author uncritically cited “Women in Refrigerators,” as if it had posed some major cultural insight, he forfeited any appearance of intellectual rigor.

Mike, in your graduate work in English you had to have learned that all critical writing concerning literature and culture has some kind of an agenda or a bias behind it. No one writes in a vacuum, and no one writes _critically_ without some sort of ideology underpinning their writing. If Lepor doesn’t write from a feminist perspective, she writes under SOME perspective. Pretending that academic writing in the humanities is somehow objective as long as it steers away from feminism, marxism, liberation theology and the like is a a bit myopic. And also something of a joke.

If having two wives and being into bondage is odd, I don’t want to be right!

In all seriousness, I’m surprised Social Justice Warriors haven’t arrived to complain about you saying WMM’s lifestyle was odd.

>>>Is it truth, or biased feminist opinion?

Yeah, the author of the book lived with Margaret Sanger’s niece. WHAT POSSIBLE CONNECTION COULD THERE HAVE BEEN BETWEEN THE TWO?????????????????

I recommend LePore’s books about American history, especially a really important book about King Phillip’s War, The Name of War:

King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity. It blew my mind, especially after reading the summary in Nathaniel Philbrick’s book Mayflower. I think LePore’s Name of War should be required reading regarding the early New England colonists and the people they met. Here is the first chapter, courtesy of the NYT,

http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/l/lepore-war.html

and a video of LePore courtesy of Vimeo, here:

I read her reviews as soon as they appear in the New Yorker, and learned a lot from this one. I’ll read the Smithsonian piece, and then this book.

In midtown Atlanta, we have a dramatic version, a play (script by Carson Kreitzer, previously produced in San Fransisco, looks like) I hope to get to, in my own neighborhood, “Lasso of Truth,” produced by Synchronicity Theatre, here:

http://www.synchrotheatre.com/season/lasso-of-truth

Reviewed, more thumbs-up, in a local paper, but I can’t seem to find the review online; here’s a more critical take, from local website ArtsATL:

http://www.artsatl.com/2014/10/review-lasso-truth-synchronicity-theatre/

Jonny R raises a valuable point. I don’t think, as per the Marxists, that everything comes down to ideology, but ideology informs everyone’s POV in some fashion.

I’ve sometimes found it useful to make a distinction between the ideological and the over-ideological. The latter condition takes place when the individual expousing his POV recognizes no relative nature to his beliefs. To use Mike’s example, writers about “body shaming” are not automatically wrong to explore that subject. But when they find their chosen subject reflected in damn near everything they write about– that’s an over-ideological POV.

I was lucky enough to read an advance copy of the book and I thought it was fantastic. I think it will reach a large audience and get people thinking about the character and her creator(s) in ways that the general public don’t normally do. LePore is as good as it gets.

Comments are closed.