Matthew: While quite a few people in the UK have heard of your comic, it’s less well known internationally. Could you describe The Rainbow Orchid for people that have never heard of it?

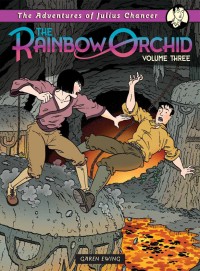

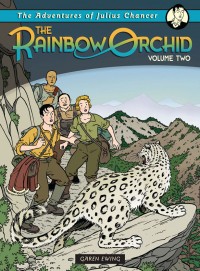

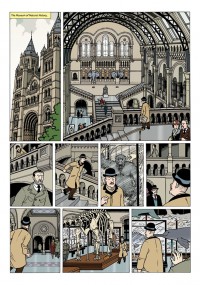

Garen: The Rainbow Orchid tells the story of an expedition to find a fantastic, possibly mythical, orchid, rumoured to grow somewhere in the depths of the Hindu Kush. It’s set in the 1920s with the main characters being a young historical researcher and a silent-film actress and her agent. I’d say it’s a sort of lost-world adventure, Rider Haggard meets Tintin!

M: Where did the idea for the story come from?

G: The catalyst for doing it was me realising that I didn’t really want to become an artist for hire, drawing other people’s comics. I’m quite slow at drawing, and I find it hard work, so it’s an extra effort for me to draw something that I might not be totally engaged with. So I decided to concentrate on commercial illustration for the pay cheque, and the comics would be just for my own amusement. The Rainbow Orchid is the result – I threw just about everything I love in there: my love of Franco-Belgian comics, the era of the silent film, and classic adventure of the kind written by Jules Verne, H. Rider Haggard and Arthur Conan Doyle.

M: Did you come up with the characters first and try to create a story to fit them, or did they come into existence as you developed the story itself?

G: I think the plot idea developed first but I was sketching character ideas almost from the start, and as they emerged that affected the evolution of the story too. I don’t remember exactly – it was quite a long time ago!

M: When did you start working on the story? Did you think it would take this long?

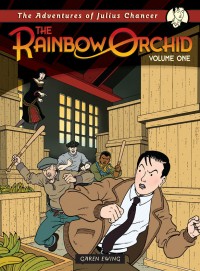

G: My initial notes and sketches were from late 1996 and I drew the first three pages in April 1997. I didn’t pick it up again until 2002 when Jason Cobley offered to serialise it in his self-published comic, BAM! I guess I didn’t really think it would take this long – there have been quite a few interruptions along the way but I knew I’d finish it one day – I was pretty determined on that front.

M: How much of the story did you have planned when you started working on the Rainbow Orchid? Did you always know how it would end?

G: Pretty much all of it, including the ending. Quite a few of the details changed en route, an extra character here and there, but it was basically all in place from very early on in my notes.

M: Why did you choose to set the book in the 1920s?

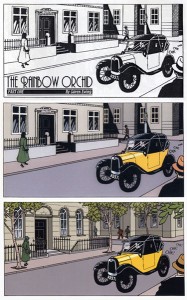

G: I’m a bit of a fan of silent-film, so that was probably the initial inspiration. I also like the fact that it’s a period that still had one foot in the Victorian era, and one foot very much in the modern age. Despite that, the world was still not fully explored, so you can have cars and planes, but still plenty of scope for the unknown. I much prefer drawing the past rather than the modern world – it’s more interesting to me, and I love the fashions and design of the twenties. The majority of stories set in that period tend to be placed in the US, with gangsters, flappers and prohibition, so setting in it Britain was a little different, especially with the scars of the First World War still very much present and the shadow of the Second World War just over the horizon – it’s a really interesting backdrop.

G: Relieved, I can move on with my life! At the moment, still quite close to finishing the story, I have mixed feelings. It contains some of my very best work, but also I look at parts and wish I’d done better. But overall I’m proud of it. I stuck with it and it exists as a mainstream-published original British graphic novel for all ages – a rare thing.

M: What else have you been working on while drawing The Rainbow Orchid?

G: As far as comics go, I turned down a number of projects in order not to get sidetracked, but I did do some work for The DFC children’s comic, initially working with Philip Pullman, and then on my own strip called The Tomb of Nazaleod. I also contributed a chapter to Nelson, published at the end of last year by Blank Slate Books.

M: What other comics have you created?

G: In the late 80s I did a fairly long running fantasy/SF comic called The Realm of the Sorceress which appeared in various fanzines. I also edited and published an anthology called Cosmorama which included contributions from Warren Ellis, Ralph Horsley, David Wyatt, Paul H. Birch, Sara Russell and many others. After that, in the early 90s, I did a comic strip adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Those are main ones, I think.

M: Would you ever want to write comics and have other artists illustrate them, or do you see yourself primarily as a visual artist?

G: I do think most of the best comics are the product of a single vision – not writing and art as separate endeavours that come together at the end, but comics, an integrated artform! That’s an ideal, of course, and many of my favourite comics are by separate writers and artists. I have written comics for others and I have drawn comics for others, both enjoyable, but not something I’m very interested in generally. I’d very much like to continue as I am, for as long as I can.

M: Egmont are the UK publishers of Tintin, but they aren’t well known for publishing newer comic work. How did your relationship with them come about?

G: After The Rainbow Orchid was serialised in BAM!, and then a self-published collection I put out myself, I decided to put the strip online – this was around 2005. That brought interest from a handful of publishers, including Gollancz and Titan Books, and through that interest I got an agent. The book was then put out to ten different publishers, of which about half responded positively – Egmont was one of those. It later turned out they’d had their eye on the strip in its web days too.

M: What’s your relationship with the company like? Are they very hands off in allowing you to do what you want, or have they been involved with the creation of the books?

G: My relationship with Egmont is very good, I’m really happy with them. Egmont are, I believe, the biggest publisher of children’s books in the UK, so I’m very lucky to have landed a contract there. The design and editorial team have been excellent, just in putting up with me, if nothing else! Tim Jones, my commissioning editor, is a genuine comics fan and a real advocate of my work, so I’m really grateful for that. On a creative level I’ve had complete freedom. Editorial input has been minimal – mostly clarity of dialogue here and there and discussions over where a comma should go!

M: What was your process like for creating the Rainbow Orchid? Did it differ from how you have created other comics?

G: As you can imagine, over such a long period, my methods have changed somewhat, and I’ve learned a lot about my own creative process. Scripts start out as free-hand, sketching as I go and creating thumbnails of the pages. Then I type up the script into a second draft. Next I work the thumbnails into lettered A4 roughs, and then it’s on to the final artwork.

M: How did you create the artwork? What tools did you use?

G: I pencil (H or HB clutch pencil) onto A3 bristol board, ink with a dip pen (Hunt 107 nib and Winsor & Newton indian ink) and then scan it into the computer. I colour it in Photoshop.

M: Your artwork for The Rainbow Orchid features many details, what sort of research do you do for the book?

G: Loads of research! Probably too much research! As I went on, I got more and more diligent, some would say pernickety, about getting things right. If the internet didn’t supply the answer then I’d seek out second-hand books that might. What colour were the trains in the 1920s on the Northwest Frontier of India? Did clothes back then have elastic? What kind of aeroplane could fly someone from Cherbourg to Karachi in 1928/29? etc. I consulted experts in some cases, for instance providing translations for the Ancient Greek and the endangered Kalasha language.

(A train in Karachi, the 1920s Northwest Frontier of India.)

M: Your art is reminiscent of the ligne claire style of drawing, how would you describe your art style?

G: Yes, I suppose I’d say it’s sort of ligne claire with extra fiddly bits. A French critic once said that I definitely wasn’t ligne claire, but most people use that as the term to describe my style. It’s certainly in that area of things.

M: Which ligne claire artists are your favourites? Are you aware of other modern artists creating comics in this style?

G: Well, favourites include Hergé, of course, and a number of his studio assistants who went on to their own strips, especially the great Edgar P. Jacobs, also Roger Leloup and Willy Vandersteen. I really love Yves Chaland. There are indeed still artists drawing in the style, especially on the continent – Eric Heuvel, Oliver Marin, Floc’h, Solidor, Jason, etc. It depends how wide you cast the ‘ligne claire net’, I suppose. There was a wonderful little US book called City of Spies drawn by Pascal Dizin a couple of years ago.

(Garen’s version of Yves Chaland’s Freddy Lombard.)

M: Who are some other influences on your work, both story and art-wise?

G: I think it was discovering the work of Jacobs that set me on the path to working in that style myself. I’d been heading towards a cleaner line anyway and seeing La Marque Jaune [published as The Yellow “M” in English] pushed me over the edge. When I was a teenager I used to copy prints by Kuniyoshi and Taira, and Tintin, alongside Asterix, were some of my first comics – so I very quickly felt at home drawing that way. Story-wise my influences come from the novels of Verne, Haggard and Conan-Doyle, and some of those wonderful 1930s film adaptations – She and Lost Horizon, as well as King Kong. The films of Kurosawa and David Lean are big influences, but I don’t know how they come out in my work – probably not very near the surface.

M: The ligne claire style is one that, at least to North American eyes, seems tied to both mainland Europe and the past. What inspired you to draw the Rainbow Orchid in this style of art? What has the reaction been to your work been like? Have you been surprised by it?

G: It really goes back to the idea that I wanted to do something purely for my own enjoyment, not thinking of an audience or a demographic or anything like that (except that I wanted it to be okay for kids and adults to read). Franco-Belgian albums were – and are – my favourite comics, so I indulged myself. The fact that other people seem to like it too is a massive and very welcome bonus.

I don’t think it’s necessarily an easy sell for Egmont – it’s kind of marketed as a kid’s book, which is great, and I wanted it to be for all ages, but the plot is a little complex in places – I like a multi-stringed story! Also, I’m not sure that adventure comics that don’t have zombies or massive gun fights are very cool, and neither is it comics lit, so it’s a bit of a challenge to get it out there in a market that’s full of US and Japanese imports, nostalgia collections and literary adaptations. There are a handful of very fine original British graphic novels being published, but it’s making people aware of them that’s the problem. But yes, I’ve been surprised and delighted by the reaction – I’m really grateful.

M: Hergé was known for using assistants to do research and draw parts of his Tintin books. Have you worked with anyone else on the Rainbow Orchid or has it been a solo endeavour? Would you ever want to use assistants?

G: It’s all me, no assistants. Sometimes I’ve thought of caving in and hiring a colourist, but there’s so little money involved that would be hard to justify. And anyway, I kind of like the fact that I’ve done everything myself, for better or worse. I’m not a very good letterer so I designed and made my own handwriting font which Egmont use. I even designed the title graphic myself.

G: Hm, I couldn’t say how many differences. I stopped myself from doing too many, even though by the time volume one was published by Egmont in 2009 the bulk of the book was a few years old. I extended a couple of scenes, in one case (the banana warehouse chase) to add a little more action, and in other (the plane taking off) because I didn’t do it very well the first time round. Maybe 10-15 panels in volume one had changes made to them, either just a figure or the whole panel. If I changed everything I wasn’t totally happy with … well, that way lies insanity!

M: Is there anything in the first two volumes you’d like to go back and change now if you could?

G: Yes, loads. I wish I’d had the time and space to extend volume 3 by about 10 pages, because I’m aware it gets a bit explainy in the middle for a couple of pages. And the art in volume one could do with an overhaul. But the best thing to do with a comic is finish it, put it down, learn from it, and go and make a new and better one.

M: You originally self published the first volume of Rainbow Orchid. Do you have any interest in self publishing more of your work in print?

G: Oh yes, definitely. I love self-publishing, I even think that may be where the future lies. But you can’t deny the clout a big publisher gives you, not to mention the distribution and print quality, so – at the moment – that would still be my first choice. I will definitely be self-publishing some supplementary material, annotations, for instance.

M: You created Charlie Jefferson and the Tomb of Nazaleod for the DFC, what was it about?

G: The DFC, which was a weekly children’s comic published by David Fickling Books, wanted an ‘artefact-based adventure’, so Nazaleod was my attempt at that. It was basically about an 11-year old kid who has to collect four mysterious stone pendants before this evil professor-chap get his hands on them and is able to activate an ancient magic.

M: How much of it was finished before the DFC was cancelled? Are there any plans to create a completed version?

G: I got about halfway through – 26 pages. I’m not sure I’ll ever return to it. I liked the idea but I chopped it up into episodes that were probably a little too short. I might put it online at some point, or I might cannibalise the plot for a future Julius Chancer adventure.

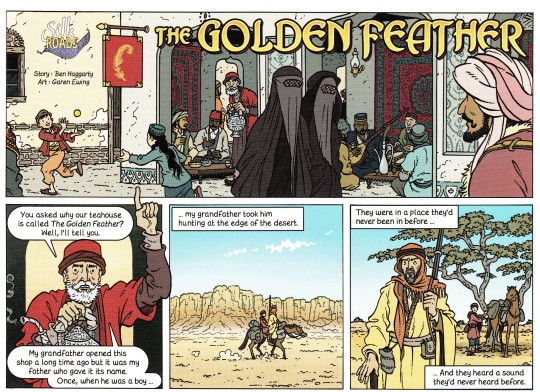

M: You recently drew The Legend of the Golden Feather for The Phoenix, the successor to the DFC, what was it about?

G: That was just a little 4-pager, written by Ben Haggarty, to introduce the story of the Phoenix, the flamey bird, in the first issue of the comic. I’m doing a longer story for The Phoenix now, also written by Ben, called The Bald Boy and the Dervish – an Arabian Nights style adventure – really good fun.

M: What’s your next project? Will there be more Julius Chancer adventures?

G: After I’ve finished the Bald Boy I’ll turn my attentions again to Julius Chancer. I have a story for him in some detail all plotted out, and a couple of other skeleton ideas. There will definitely be more, though I wouldn’t do another three-volume story – something more manageable.

M: I saw you mention an interdimensional time-travelling adventure in some other interviews, have you worked on this idea at all?

G: That was for The DFC, just before I did Nazaleod. They liked it, but because there was already a series that had a bit of a time-travel theme they wanted to save it for a future run, which never happened, unfortunately, as the comic folded due to cuts by Random House. I really liked the idea, but I’m not sure I’ll ever have the time to do it as a comic – I’m too slow, I have to keep myself to one project at a time, and I want to concentrate of Julius Chancer for now.

M: As far as I know, the Rainbow Orchid has only been printed in the UK, do you know if there are any plans to release the book in North America?

G: There are currently no plans for a specific US-edition. There is a Dutch edition published by Silvester Strips – volume 1 came out in 2010 and volume 3 is coming out this June. I’ll be at Stripdagen in Haarlem to launch it. I have also signed contracts for two other languages, but as they’re still going through I won’t go into details yet!

M: And finally, did you see the recent Tintin movie? What did you think?

G: I did get it to see it eventually – it’s the only film I saw at the cinema last year! And I really enjoyed it, I thought it was a great romp, though it flagged a bit towards the end. There were times when I forgot the story and instead found myself marvelling at the technical wizardry. It didn’t hold up on a second viewing on DVD though – still an enjoyable story, but I found the characters weird to look at … hyper-realistic bodies with these grotesque rubbery faces! But, you know, overall, lots of fun. It’ll be interesting to see if it has any effect on the popularity of the Tintin books in the US, a market Hergé never really cracked.

You can keep up with what Garen is currently working on, and read a preview of The Rainbow Orchid, on his website.

==========

Matthew Murray reads a lot of zines and comics, but he always wants more.

Wonderful work! Thanks to The Beat for opening my eyes to this series. This is the kind of reporting (good news story) and interview that really brings home what I like in comics.

Don’t get me wrong, I like my American-style superheroes, as well. It’s just nice to see coverage and in-depth across the board. Or maybe I just woke up on the right side of the bed today. Hah!

This looks incredible! Obviously, heavily influenced by TINTIN but it looks like it hits on just about everything I like. Thanks for sharing.

Great interview Matthew. We need more of this stuff. Get to it.