By Jeff Trexler

In the book of Genesis, Esau sells his birthright to his younger brother Jacob for some lentil soup.

Yesterday, a judge ruled that Joe Shuster’s sister sold the family’s claim on the Superman copyright for a meager pension.

Superman may be a modern myth, but that’s not always a good thing.

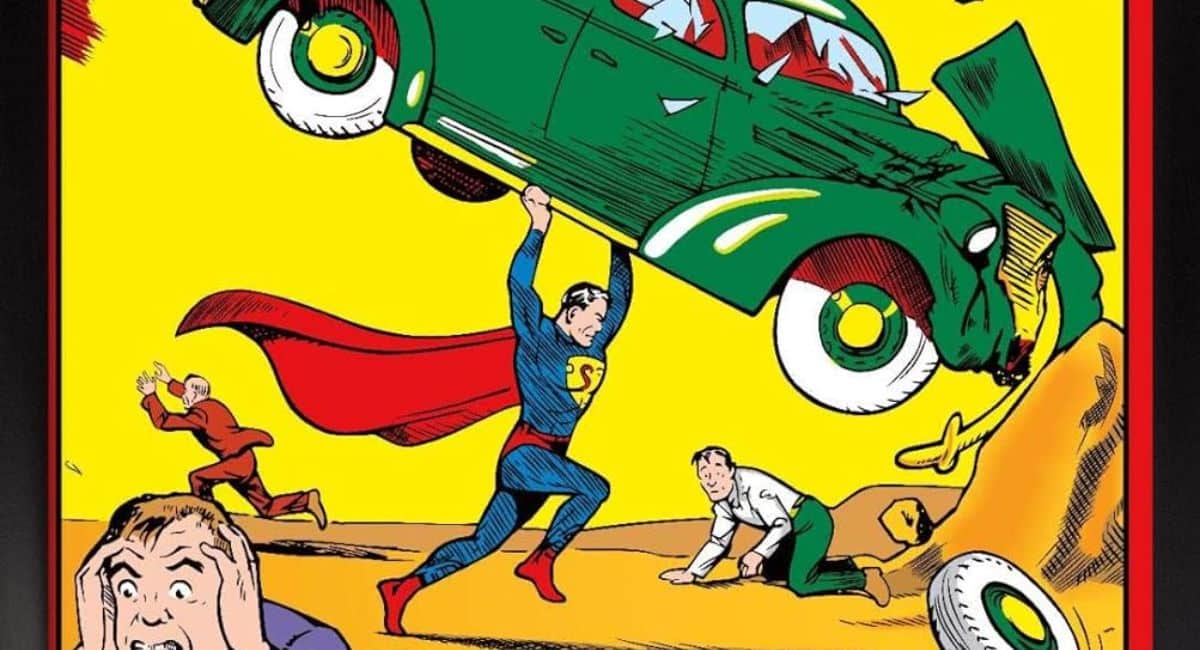

When I read that the district court had ruled in favor of DC Comics in regard to the Shuster termination claim, my immediate response was well, of course.

And then I got angry, but not for the reason you might think.

The Termination of the Shuster Termination Rights

In 1992, Joe Shuster’s sister signed an agreement waiving all future claims in exchange for a $25,000 a year pension and DC’s covering Joe’s outstanding debts. At the time she thought she had struck a fantastic bargain, and she repeatedly told DC that she was not going to try to reclaim Shuster’s half of the Superman copyright.

As I indicated in previous posts, this posed a real threat to both the termination claim filed by Shuster’s nephew, Mark Peary, as well as the Siegel victory. If–as seemed quite possible–the court ruled against the Shuster termination, DC would own half of Superman outright, leaving the Siegel family with far less leverage to get the company to be more generous.

The case seemed pretty strong in DC’s favor, but still, there was a shot it could go in the other direction. As we’ve seen in the landmark Siegel case sometimes a court can find creative ways to reach what it deems be a more equitable result. Indeed, Judge Otis Wright had made some comments in a recent hearing that could have been interpreted as a sign that he was going to be as creative with the Shuster claim as the previous judge had been with Siegels.

Not this time.

The problem was that the Shuster claim was not the first of its kind. Other families have tried to get out similar bargains–most famously, the heirs of A.A. Milne and John Steinbeck–but the precedent established in these cases worked against the Shuster claim. As Judge Wright observed yesterday, courts have not interpreted copyright law to allow families to reclaim termination rights after using them as a bargaining chip in a deal. Like Esau, Joe Shuster’s sister had traded long-term rights for short-term gain, thereby cutting her child out of a far greater inheritance.

The Hollow Victory of Superman’s Lawyer

Why didn’t the judge take a flyer and try to find a clever way to help Mark Peary? Perhaps it truly was the force of the law, but the ruling also indicates that the actions of attorney Marc Toberoff did not make Peary’s claim seem just.

To see why, we need to look at a part of the case that most news reports have ignored–namely, the judge’s other finding that went against DC Comics.

Besides relying on the 1992 agreement, DC Comics had argued in the alternative that Peary’s termination claim was invalid because Peary had transferred his share of the Superman copyright to Marc Toberoff’s production company, Pacific Pictures. Given that the judge had already found the claim invalid because of the 1992 agreement, this issue was technically moot and the judge really didn’t need to decide it.

But decide it he did. Judge Wright wryly noted that Peary hadn’t relinquished his share–Toberoff himself conceded that Peary never actually sold his rights because the sale itself was illegal. Copyright law does not allow the prospective sale of rights to be granted by termination prior to the filing of a termination notice. Since the transaction between Peary and Toberoff took place before such a filing, it was null and void.

Judge Wright agreed with Toberoff on this point, but the ruling makes clear that this is not a victory for the defense. Peary and Toberoff willfully entered into an illegal contract, one that Toberoff, as a copyright lawyer, should have known was illegal and void. Peary then failed to disclose pertinent details affecting the Superman copyright to the Copyright Office. The judge went on to note that while it is a general principle of law that defendants can’t rely on the illegality of their actions to get out of a contract, in this case ratifying the agreement between Toberoff and Peary would constitute a fundamental violation of the copyright statute.

In short, in Judge Wright’s eyes Peary and Toberoff were not the good guys here. He not so subtly portrayed them as bad faith lawbreakers trying to take what they do not deserve.

What next?

Last week we saw a public letter by Laura Siegel praising her noble attorney Marc Toberoff as he fought the good fight against DC. Assuming she wrote that letter and conducted the PR campaign by herself (cough cough), I have to say Judge Wright’s latest decision only underscores the need to think seriously about what the Siegel family could lose.

The 2008 victory was historic, but it was not a slam dunk. It could have easily gone the other way with far less legal stretching, and it is still possible that the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals could reverse or vacate it. The effect would arguably be even more devastating than if the Siegels had never won at all.

Even if they win, it’s not clear how much the Siegel family will actually gain–there is still a rigorous allocation process to go through, with a substantive chance for a finding that the Siegel share of the current property is far less that 50 percent. A successful termination by the Shuster estate could have provided leverage to get DC to strike a better a deal, but that’s gone–and the odds are in DC’s favor that it will not be reversed.

What should the Siegel side do next? They could fight to the bitter end, but they need to ask what they’re fighting for–Jerry Siegel’s legacy or Marc Toberoff’s?

Perhaps it’s time to pursue two settlements.

The Shuster ruling, coupled with the material provided in DC’s ongoing action against Toberoff and Pacific Pictures, gives the Siegel family ammunition in pursuing a settlement (under threat of a lawsuit) that could reduce if not eliminate Toberoff’s financial interest in their claim.

They could then pursue a settlement with DC under the previously agreed upon terms. The earlier settlement offered by DC wasn’t perfect–indeed, if you read it with an eye to legalese & corporate accounting you’ll see it wasn’t all that great in terms of the overall value of the Superman property. However, it was exponentially better than the 1976 stipend and what Joe Shuster’s sister got in 1992, and it gave the Siegel family a multimillion dollar payout with no risk, no turmoil and little money going to lawyers.

Shuster Superman copyright ruling – October 17, 2012

A key provision of the Bono Act is that no previous agreement can nullify the creator’s right to reclaim copyright at the 40-year mark:

17 USC § 203 (a) (5)

“Termination of the grant may be effected notwithstanding any agreement to the contrary, including an agreement to make a will or to make any future grant. ”

(This was a key element of the Joe Simon/Captain America case, because 17 USC § 203 (a) says this only applies to works other than work made for hire, and Simon’s revised agreement asserted that Captain America *was* created work for hire; the court ruled that agreement was binding.)

In the case of Superman, there is clearly grounds for deciding that (some portion of) the work was not “work made for hire”, and that the Siegel/Shuster heirs should be able to revoke the original transfer (on at least some portion of the work). So it boggles me that a judge would simply rule that there was no validity to the termination, even given the bad faith practiced by the lawyers. That seems like a textbook example of babies and bathwater.

Thanks for this “plain english” version of the latest twist in this case. As a creative, I’m watching this very closely and am dealing with very mixed emotions and reactions. The only opinion of mine that I’m willing to go public with is that I do hope this gets resolved soon and the decision is fair and just for all involved. This whole case is an excellent example of how copyright law needs to be changed to reflect the work and life’s blood that creatives give to their work.

The future for creators retaining the IP of their characters seems so much brighter. This is a horrible lesson everyone will learn from and never sign away their ideas.

“This is a horrible lesson everyone will learn from and never sign away their ideas.”

I’m all for people keeping control of their ideas…as long as they also understand that they’ll almost certainly never come up with anything one-millionth as good or successful as Superman AND that they shouldn’t expect a work-for-hire avenue of employment to survive if nobody ever contributes anything new to the proverbial toybox.

Mike

It seems to me it’s incumbent upon the work for hire entity to make it worth a creator’s while to add to the toybox, with creator credits, participation, etc. If DC and Marvel want new contributions to their universe, they really need to make sure the creator of a successful property sees a decent back-end benefit, as well as the initial up-front payment for services rendered.

Also, characters are not all equally valuable. The value of owning a character is connected to the frequency with which he’s used. A single classic story and its characters can be reprinted endlessly, licensed to other media, used on merchandise, etc. Superman is more valuable than other characters, such as Lex Luthor or any of the other villains that Superman has fought. The hero’s virtues are eternal; the villains are created to be defeated and broken.

SRS

Kevin, thanks for bringing up the Joe Simon/Captain America case. I’d thought about including a section on that but left it out primarily for length reasons. Question = reason to include!

Judge Wright addressed the issue of the prior agreement provision in the opinion. His reasoning expressly followed the Steinbeck case, whose fact pattern was analogous to that in the Shuster termination claim. Relatives had entered into an agreement that waived any prospective termination rights in exchange for an immediate benefit. The Steinbeck court found that such an agreement was outside the scope of the statutory provision regarding previous agreements, and Judge Wright agreed.

Judge Wright didn’t continue on from the Steinbeck paragraph quoted on page 9, but if he had, it would have been clear that courts have already distinguished the Simon case. Here’s the relevant paragraph from Steinbeck:

“Appellees’ reliance on Marvel Characters, Inc. v. Simon,310 F.3d 280 (2d Cir.2002), is misplaced. There, the parties entered into a settlement agreement that contractually recharacterized an already created work as a “work made for hire.” Works for hire are exempt from section 304(c) and (d). We agreed with the author that the grantee could not use such after-the-fact relabeling of the nature of the work to eliminate a future exercise of the author’s termination right under section 304(c), because the contract constituted an “agreement to the contrary” that left termination rights unaffected under section 304(c)(5). Id. at 290. We were concerned that if such an agreement was not held to be an ineffective “agreement to the contrary,” authors could be coerced into recharacterizing works already created as works for hire so as to avoid subsequent application of a section 304 termination right. Marvel concludes only that backward-looking attempts to recharacterize existing grants of copyright so as to eliminate the right to terminate under section 304(c) are forbidden by section 304(c)(5). There was no such attempt at recharacterization here.”

There are a couple of things at play here.

One is a formal black letter legal distinction between a post facto re-characterization of a previous agreement versus an agreement that rescinds & replaces previous agreements with a contract whose value also reflects possible prospective rights. Different contracts with different bargains and effects–the termination provision nullifies one but doesn’t affect the other.

Why not? That gets the the second and more important concern: fairness. In the Simon situation, Marvel arguably used its power to exploit Simon through an unfair deal. The termination provisions were in part designed to address exactly that sort of inequitable imbalance.

In the latter situation, however, the heirs were aware of the potential value of possible prospective termination rights and used that as a bargaining chip to strike a deal they saw as advantageous. Allowing heirs to subsequently use the termination law to get the copyright back despite such their previous agreement would be unfair to the other bargaining party in a way that undermined the integrity of contracts.

Sure, it may have only been unfair to a big corporation, but it was unfair nonetheless–there is no “corporations suck” rule in contracts, especially in New York.

Correction–third paragraph, line 2 should read “quoted on page 12.”

Every time I hear people talk about the creator vs the corporation, I think:

1. Jerry and Joe, while they were the original creators, are not the ONLY creators of the Superman property as it exists today. Several key people in the creation of the overall Superman property were DC executives.

2. Jerry and Joe settled with DC. Multiple times. They were also extremely well paid back in the day, and due to their own poor financial choices and other bad business decisions (Funnyman anyone?), blew through their savings.

3. Jerry and Joe are not fighting this fight. Others are. These others are not the creators. In fact, the key person in this fight (Toberoff) is not a creator, is not related to the original creators, and is essentially a corporation in itself. So it’s not a “little guy vs a big evil corporation” it’s a “millionaire lawyer vs a corporation for his own personal gain.”

Personally, I’m of the opinion that, when you sell something, you sell it. And that’s it. No Indian givers allowed.

Can we get Superman an order of protection against Dan Didio?

While I’m not a lawyer (duh), Trexler’s explanation here sounds to me like the court is saying that Shuster’s sister in essence *pre-sold* her 1998-2003 termination rights in 1992. In that context, what it means is that, because she already sold them, her rights can’t be sold twice. Any way you try to spin it, it boils down to “you can’t terminate rights that you don’t have due to the mere fact that you already sold them.”

Or, in other words, the 1992 agreement is a binding contract.

Moreover, I’m inferring from the article and the self-evident nature of the judgment against Shuster that there’s some kind of boilerplate language in the 1992 contract that specified that Shuster agreed to abandon all future rights termination opportunities.

The evidence is clear: Shuster knew what she was getting into in 1992. No matter how much we want to see Joe Shuster’s estate get the tens of milllions of dollars that he and Siegel were screwed out of by DC throughout their lives, Shuster’s sister willingly sold those rights for a song. DC’s past misconduct does not in any way, shape or form validate Petrocelli and Peary’s current misconduct, which could not ever and cannot ever even hope to rise to the level of poetic justice.

Great analysis as always, Jeff. Rob J.: you are right in that it was a binding contract, and as we now see, legally enforceable, but there is context here too. Jean Peavy did all of this negotiation through personal letters to Paul Levitz. She had no legal counsel, which was very apparent. In her words, this was just “the way to do business with family.” She felt like DC was finally taking care of her. Levitz then inserted the contract language and that was that — though I’m fairly sure no lawyer would have ever instructed her to agree to it. Again, context doesn’t matter as far as the legal result here, but it is important to the story. And it remains a shady story.

J.K. Rowling says hi. Robert Kirkman says give me time. George Lucas chuckles and counts his money for the 30th straight year. Superman is great, don’t get me wrong. But creator-owned can be a lucrative avenue too, as long as it manages to capture the zeitgeist.

Jonboy, really no Indian Givers? You do realize that is not only a racist comment but is the quintessential case of one group of people taking unfair advantage of another. Kind of negates your argument.

Let’s say the court upholds the summary judgment awarded Laura Siegel Larson. Let’s say Marc Toberoff has a controlling interest of the percentage of Superman awarded as a result of that summary judgment. In that case Laura Siegel Larson still owns a percentage of Superman. How is that worse than Warner owning all of the Superman copyright? And what did Toberoff win again? It was a summary judgment. That sounds to me like the previous attorney wasn’t representing his client very well. And as I understand it Warner says their generous offer is still sitting there on the table.

Clearly this runs a lot deeper than money for Laura Siegel Larson. She’s probably at an age where the money doesn’t matter that much to her. The fact is trail lawyers working on contingency are one of the favorite targets of corporations. Yes everyone knows they get very large rewards IF they prevail in court against corporate giants like BP, Monsanto, Disney, or Time Warner, but hey go ahead Mr. Private Citizen and take on one of those behemoths with money out of pocket and see where it gets you. Go ask Gary Friedrich how well that works. The thing is if you are going up against G.E. or Philip Morris you better hope your attorney has a very strong motivation behind him and a very large reward at the end of the rainbow, because it’s an epic battle.

Regarding Point 1, the case that the Siegels won specifically carves out the IP contained in the first issue of Action Comics that was created and submitted to DC, not commissioned by DC. There’s an avalanche of Superman-related IP that the Siegels have no ownership of.

As for the rest, thankfully, in legal matters it doesn’t really matter what anyone’s personal opinion is.

(Oh, and I’m a different Jesse than the one above, though I approve of his excellent choice in first names.)

Not only won, but won on summary judgment. The: “Time Warner” good-Toberoff bad” arguments in various places aren’t logical. No matter what share Toberoff would end up with if the summary judgment is upheld, Laura Siegel Larson would have a portion of that share. That is a B&W contrast to Time Warner owning 100%.

Jeff–

Thanks for posting the Paul Levitz correspondence with the Shuster heirs. It’s clear that DC bent over backward to be generous with them.

I was especially struck by the 2005 proposal DC offered in exchange for the Shuster heirs not filing a termination claim. DC offered a two million dollar advance against a royalty deal that would pay a minimum of $100,000 a year through 2033. And the heirs obviously didn’t have a legal leg to stand on after the ’92 agreement; DC just wanted to avoid the hassle of beating back a termination attempt.

The letters make it quite understandable how Joe Shuster went broke. And I have to say that the Siegels were rather sleazy in their dealings with him. Reading that they charged off 20% of his pension in exchange for “negotiating” the increases from DC over the years made me kind of ill.

Great article! I’m not surprised based on Larson’s questionable behavior (ruling combined with new career field) . Don’t be surprised if the Siegels lose 90% of what little they earned, I still see them losing those 2 weeks of comics strips and the Superman 1 comics (minimum). DC also has a strong case for the ads/cover and coloring.

If Siegel had gone to Marc Toberoff, then you might have a point. The fact remains Marc Toberoff went to the families while they were closes to settling.

Also it is stuff like this that mark Mark as “the bad guy”;

“Peary and Toberoff willfully entered into an illegal contract, one that Toberoff, as a copyright lawyer, should have known was illegal and void. Peary then failed to disclose pertinent details affecting the Superman copyright to the Copyright Office.”

In short, the issue is not that Marc is playing the game, its that he is playing it illegally or at least per this judge’s opinion. Now we can always talking about one judges ideals over another but the difference here is that Otis is not stretching the law or being “creative” to administer rulings.

Comments are closed.