[This weekend, Clutter Magazine and Midtown Comics are teaming up to bring a new kind of convention to New York City. Part comic-con and part toy-con, Five Points Festival “is a celebration of art and its creators – whether they make comics, toys, beer, or Korean vegan tacos.” As part of that celebration, they’ve partnered with the Comics Beat for a series of interviews with some of the festival’s guests – and some of the hottest talents working in the industry – to spotlight the creative process and creator concerns. ]

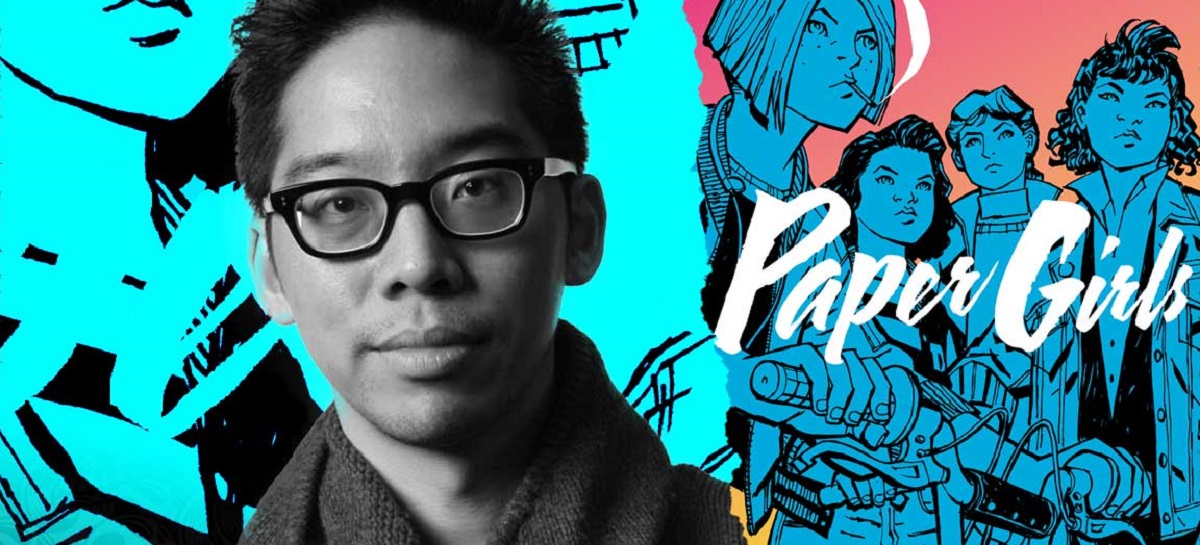

In this in-depth conversation, Chiang sat down with the Comics Beat to discuss a variety of subjects. We cover his origin story, his artistic influences, and how his style has changed over time. We also explore how he relates to his Asian-American heritage and how he views his role in the comics community. Finally, of course, we discuss Paper Girls, the eighties, and the process of making a book that feels like “live jazz.”

Chiang: My older brother started bringing them home. I knew about them and had seen them around before, but it wasn’t until maybe I was about 10 that my brother started buying them and bringing them back to the house. It was really the perfect age to be introduced to comics because when you read a single comic back then, there were so many references to other comics. The way the stories were told made you feel like the book was a window, a glimpse into this really giant world of storytelling. They really pulled you in.

Lu: Did you ever have that sort of a-ha moment when you were kid when you realized that people actually made comics and you could be one of those people?

Chiang: No, I never did. From reading stuff like Stan’s Soapbox, I knew that people wrote, drew, and colored comics—all that stuff—but I never really thought about it as a profession. I never thought about comics being made by people or wanting to be one of those people. It was just unthinkable…it didn’t broach my mind as a possibility. It wasn’t until kind of late in college that I realized I wanted to be creative and that that was going to be a goal for me.

Lu: Speak to me about that journey a little bit. How did you come to find that you wanted to do something creative?

I knew that and tried to be practical, but I really didn’t know what I wanted to do. I kept coming back to storytelling. I thought about being a film maker. I studied English-Lit and then ended up adding a Visual Arts major to that as well. I came out of school with a degree, but my focus was comics.

I wanted to work in comics but I knew that it was a small industry and hard to get your foot in the door. I was willing to do whatever I could to just sort of bide my time until a job opened up somewhere, so I worked at an ad agency for about six months as a junior art director. I kind of hated it. I wasn’t very good at it and the work itself was pretty dry. However, in terms of just having a pay check, it was great.

As soon as a job opened up at Disney Adventures Magazine with Heidi MacDonald, I interviewed for it and got it. I spent the next year or so working with Heidi, editing about 20 pages of comics a month with multiple teams. It was a great introduction to how comics are made.

Following that, another position opened up at Vertigo. I did that for a few years. All that time was spent learning the intricacies of what it’s like to make comics. At the same time, I worked on my own drawing on the off hours because as much as I wanted to draw comics, I wasn’t really ready to do so professionally, even though I would have jumped at any opportunity.

After two years at Vertigo, I went freelance. I felt like I was in position to somehow start getting work because I was in contact with a lot of editors. They knew me and they knew I was dependable and trustworthy, which goes a long way when you’re hiring someone for the first time. I was at the office all the time just seeing friends. I would inquire with people and ask if there were any small jobs available. I slowly put together a working portfolio of published pieces piecemeal—short things in “Secret Origins” or one page in “Who’s Who”—that kind of thing. Slowly, you start to become someone who’s done a few things and is no longer wet behind the ears.

My parents tacitly support me in my creative endeavors now, but I think they would still strongly prefer it if I did something more stable. So, I think my greatest struggle at this point is finding internal sources of motivation to push forward when there aren’t a lot of people unconditionally in my corner. How did you work through that?

Chiang: It was what I wanted to do. I should say that I did apply to law school. I got into NYU, in fact, and deferred for a couple of years. I told them I was going to go to Taiwan. I was going to go and teach English or something like that. It was total BS, but they bought it because it was like an identity thing and it was cultural. I just had to think of the most plausible and yet unassailable reason.

Knowing that I had law school in my back pocket gave me a lot of freedom to just take whatever chances came my way for a couple of years. Then, once I was at DC, it seemed stable enough that I could let go of the idea of actually going to law school. In a way, step by step, the journey is almost like rock climbing—finding the right point of purchase so you can go to the next step.

Also, it’s never a direct path, I think. You’re always kind of weaving. You have your eyes on your goal in the distance, but you don’t expect for it to be a straight line there. You’re going to be weaving and going left to right and following other things. As long as you keep your eye on some ultimate goal I think, whatever you learn along the way can only be helpful.

Lu: What is your relationship with your Taiwanese roots?

Chiang: I’m embarrassed to say I haven’t been back to Taiwan since I was a teenager. I don’t speak the language, really. I just have whatever little I’ve retained from speaking to my grandparents over the years. I also don’t speak Mandarin so it’s difficult. Traveling to Taiwan or to Asia—or even just being in Chinatown— always puts me in this weird spot where I feel comfortable but uncomfortable at the same time. I know there’s a familiarity about it, but I still also feel a bit like an outsider, you know? I think it’s that weird liminal space of being Asian-American where you have the familiarity with the culture, but you never feel 100% part of it.

Lu: Right. I don’t speak Mandarin either. I can hear a little Shanghainese but can barely eke out a sentence. The weirdest thing for me is going to Chinatown with friends for Dim Sum. The waitresses will talk to me as though I know what I’m doing and two of my non-Asian friends who actually do speak Chinese will just be sitting there, kind of laughing!

Chiang: Right. It’s embarrassing and you know it’s not something that would stop you from going to a place, but you know it’s going to happen and you kind of have to guard yourself a little bit.

Lu: How do you explore your nationality or your roots in your work?

Chiang: It’s difficult. I think a lot of times there aren’t a lot of opportunities to do so because of the nature of superhero comics. I think more recently things have begun to open up and I’ve realized how much I enjoy having characters that are people of color. It reflects the real world and it reflects how I grew up, but for the longest time I think people just defaulted to a norm that stories should be about Caucasian people. I grew up that way never seeing myself represented on screen and I kind of just learned to live with it, as sad as that is. Now though, I’m slowly pushing myself out of that comfort zone and saying that, “no we should try to represent more,” in my work.

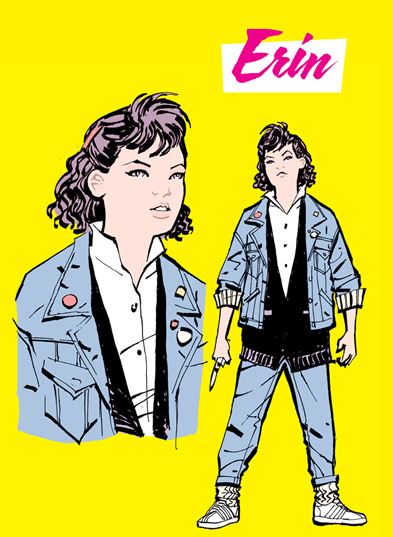

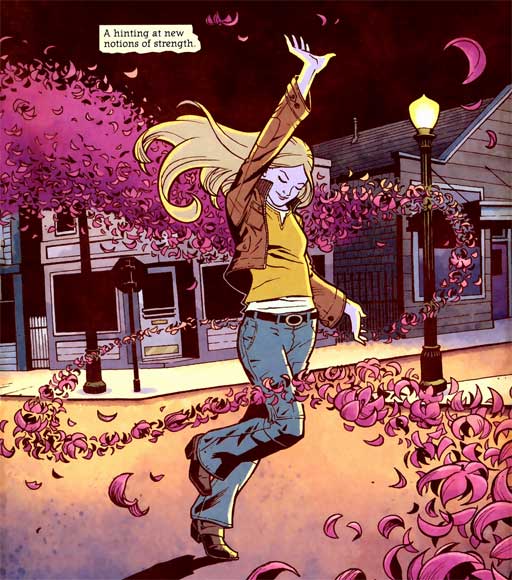

Luckily, with Paper Girls, the first two arcs are focused pretty heavily on Erin who’s Chinese-American and is basically the same age I was at the time of the story. I can remember what the world was like and what my house was like when I was 12. I remember what my other Asian friends’ houses were like. I draw on that for Paper Girls so there’s a real joy in being able to do my version of photo journalism, or comics journalism, through the story. I try to make Erin’s house and her upbringing feel authentic in some way.

Chiang: We spoke a bunch of times during the development of the story. I think Brian had a pretty clear idea of the basic shape of the story, so we talked about details, about the characters, and about the things that might happen to them. I would suggest scenarios here and there and suggest topics we might want to address. Slowly, I saw those ideas make their way into the book—the process was really rewarding.

I think Brian works very organically. He’s got an idea, but he’s also able to take others input and work that into the story to make it richer. In the best of ways, the process is a little like people just ripping each other offer—making comics is like playing live jazz.

Alex Lu: During development, did it every worry you guys that you are telling a story that’s basically entirely female-led without any female members on the creative team?

Chiang: We weren’t worried about it. We intentionally wanted to have female characters because these stories are usually so male-dominated. It’s always a boy’s of coming of age. We found that having female characters really changed the story and allowed us to approach it in a different way and open up different avenues.

We felt pretty strongly that at twelve boys and girls are more similar than they’ll be after that. At least mentally there were ways in which we could remember what we were like then and empathize with them, more than later in life perhaps. At the same time, Brian and I both had lots of primarily female friends growing up so we felt pretty comfortable, too, just thinking about what girls would be like at that age and what they were thinking about. Brian’s always been great at writing female characters. I wanted to work with Matt Wilson and Jared Fletcher again because we had been so simpatico on Wonder Woman. I think we could very much use a female voice on the team that’s for sure. But that’s just not the way the project came together. And looking back now, I wish I had thought harder about it. Representation is so vitally important to both our industry and our culture, but it takes effort and a lot of self-awareness to push through your own biases.

Chiang: Absolutely. If anything, we wanted the first issue to feel like a Stephen King novel that suddenly twists at the end. Brian’s really great at executing those last page reveals and keeping you on your toes. I think, in a way, those twists are almost to be expected!

It wasn’t so much misdirection in a way, though, as that first issue needed to establish the everyday norm for them before all the shit goes crazy. We needed to see what it was like for them to wake up at 4.00 am and get ready to go out and deliver papers. We needed to know what the logistics were and how these girls would team up to cover their neighborhood—stuff like that. It was all a fun look into what being a paper deliverer would be like back then. I didn’t have that job and neither did Brian, but he did talk to a lot of people who were paper girls and paper boys.

Lu: When you were developing your illustration style, which artists influenced you?

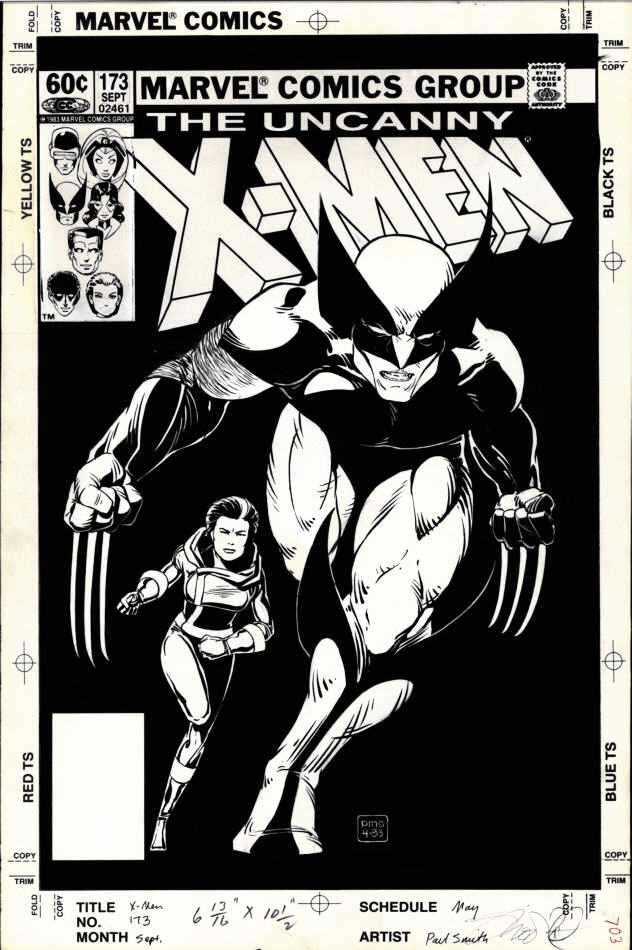

Chiang: It’s been a series of influences over the years. I can always see echoes of the things that I’ve always loved [in my work] and then at the same time, I want to push away from them. It started off with those first comics: Paul Smith, John Byrne, X-Men, The Fantastic Four…that stuff was really great. The way Smith and Byrne, particularly, told stories really spoke to me and I can see their influence on my storytelling even now. Later, when I was in college and getting back into comics, I read stuff like Preacher, Madman, and Love and Rockets. Those things started to really speak to me.

Then, when I realized that I wanted to be a comic book artist, the whole process of study really began and I just kind of inhaled every artist that I liked at the time. I tried to figure how they worked and why they worked a certain way. A lot of people like Steve Rude, Milton Caniff, and Frank Robbins have a very classical draftsmanship. I appreciated that and that’s the process. You find something that you like and then you discover the person who inspired them. You go back and back, just tracing your way through the history of comics. Jeff Smith, I think, was also influential. His work taught me how comics worked on a panel-by-panel and page-by-page basis. Everything I read was part of this self-directed education in comics.

I changed directions a few times early on. I was frustrated with the way mainstream superhero comics looked. I felt like the stuff was too precious and I wanted to see more brushy boldness to the work, similar to the way David Mazzucchelli drew Rubber Blanket. I wanted to see that kind of approach applied to superheroes. That influenced a lot of my thinking. I tried to keep my art simple and draw it well enough so that you got the most impact from it.

Then, I started getting tired of that. I started focusing on just doing finer work with pen. That clear line style showed up in my work on Human Target. Then, I transitioned to slicker and sharper, more straightforward superhero work with Green Arrow/Black Canary. Ultimately, I was trying to make myself well-rounded as opposed to just pursuing one look all the time.

Lu: Is your personal artistic process nowadays primarily digital or a mix?

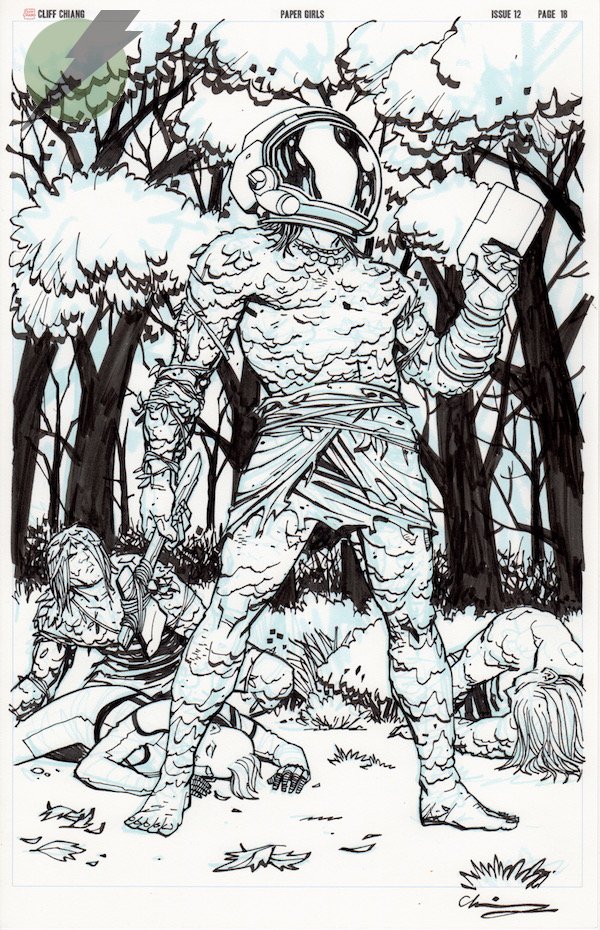

Chiang: It’s a mix. Most of my preparatory work before inks is done digitally. I do my layouts and my pencils digitally and then I print them out in blue so that when I ink, I really don’t have to be careful about it. I think being too careful is kind of the death knell for any energy in your drawing. You just going to have to attack it and hope for the best. Fly by the seat of your pants. There’s an aspect of inking that’s almost performative, too. I try to get into that headspace when I ink. It’s very separate from the more rigorous thinking that you need to do when you’re figuring out storytelling.

Lu: In some interviews, your style was described as simplistic. I don’t think that’s quite the right word. I think it comes across more like it’s designed. It’s there to do the exact amount needed to convey the information of the storyline.

Chiang: Yeah, thanks. I’ve heard simplistic before. I’ve heard minimalist, too. I don’t think that is right, either. What my art is meant to do is be very targeted about what you’re seeing and what you’re not seeing. Sometimes that means a page is minimalist and sometimes that means it’s not. Certainly, there are other people who are better at doing minimalism than I am. When I think minimalism I think of someone like Roy Crane or perhaps Eduardo Risso. Eduardo composes like he’s getting the biggest bang for his buck with everything he draws. Look at his light sources. He is content to blow things out where there isn’t much of a background because of the way the light is cast or to just bathe the page in black. It’s all beautiful, but my mind doesn’t always go there. I think, if anything, my art is high contrast.

Chiang: It’s left open very purposefully. After working on Wonder Woman, I found that the way I spot blacks can sometimes lead to there not being enough depth in the panels. Curiously though, we’re using a very pale palette in Paper Girls to let the line work come through a bit more despite my intent to open it up. We’re using color temperature in a way that gives us depth and relying less on contrast. As a result, I think the book is very easy to read. We’re trying to keep the book from being too fussy, going with a very flat coloring style to avoid doing a lot of modeling and shadows… if you over-model these things then they start to look grotesque.

Lu: Did you ever consider pursuing a more photo-realistic illustration style? Around the time when you first started working professionally, that style started coming into vogue.

Chiang: No, but it’s funny that you say that actually. When I was learning to draw, I felt like I could go in one of two directions to reach the next level. I could go in the direction of Michael Lark and Jean Paul Leon with photo references, or I could move towards Paul Pope’s style.

Ultimately I decided that photo reference wasn’t the direction I wanted to go in. The stuff that made me the happiest and most excited, creatively, was the stuff drawn by artists that had styles that felt so immediate and casual that they almost felt like a signature. It was just like handwriting for them. I wanted to draw like Jordi Bernet and Joe Kubert—you can see their lines being laid down almost unconsciously, yet they’re right and unmistakably theirs. I felt like if I had started going more photo ref based I would have been too reliant on it and abused it because I didn’t know enough about drawing.

Chiang: It’s a good question. I feel that at least, my role at the bare minimum is to represent Asian-American culture or Asian-American characters in comics whenever possible. Not necessarily just Asians, even…I feel like as people of color, we’re more sensitive to how other ethnicities are portrayed. We need to make sure that we all do a better job of representing the world.

On a creative level, I think we need to make sure that when we do come up with new stories that we don’t default to white and male all the time. It’s not necessarily wrong to have white and male characters and stories, but we should think more carefully about what our choices are because I think comics now have an audience that’s broad enough that you can tell all different kinds of stories.

Recently, I went to MoCCA. The number of female Asian faces I noticed at the tables was astounding. It just made me think that things are going to change in the next 20 years for sure. It’s a question of how fast we get there. The face of comics will absolutely change.

Lu: Would you ever consider going back to do another superhero story? Rare as they are, there have been some real breakouts like Ms. Marvel and New Super-Man who present a new, more diverse take on the superhero narrative.

Chiang: Yeah, I think I would. It would be an interesting challenge to take on a character creatively and have a mandate like that where this is what you’re going to do. The way that, say, Greg Pak is doing with The Incredibly Awesome Hulk or G. Willow Wilson is doing with Ms. Marvel. It’s an interesting nut to crack and I think that would be something I could see myself doing. At this point it’s hard to see past Paper Girls to what’s next, but that’s certainly something that’s worth doing.

Lu: Paper Girls has been going on for almost two years now. How long do you see it going for?

Chiang: We’ll be going for a few more years at least. We’ve got more story to tell.

Paper Girls #15 hits shelves on June 7th.

Check out our earlier Five Points Festival Interview with Matt Rosenberg!

Great interview!

great interview with a great creator and person! So thoughtful in his approach and any aspiring artists out there should pay attention to his approach to the craft.

i think it’s also the first time “LIMINAL” has appeared on the internet, so kudos for that! :)

thanks for the great conversation!

Thanks for the interview! I think I saw Paper Girls in passing, but now I’ll give it a shot~

Comments are closed.