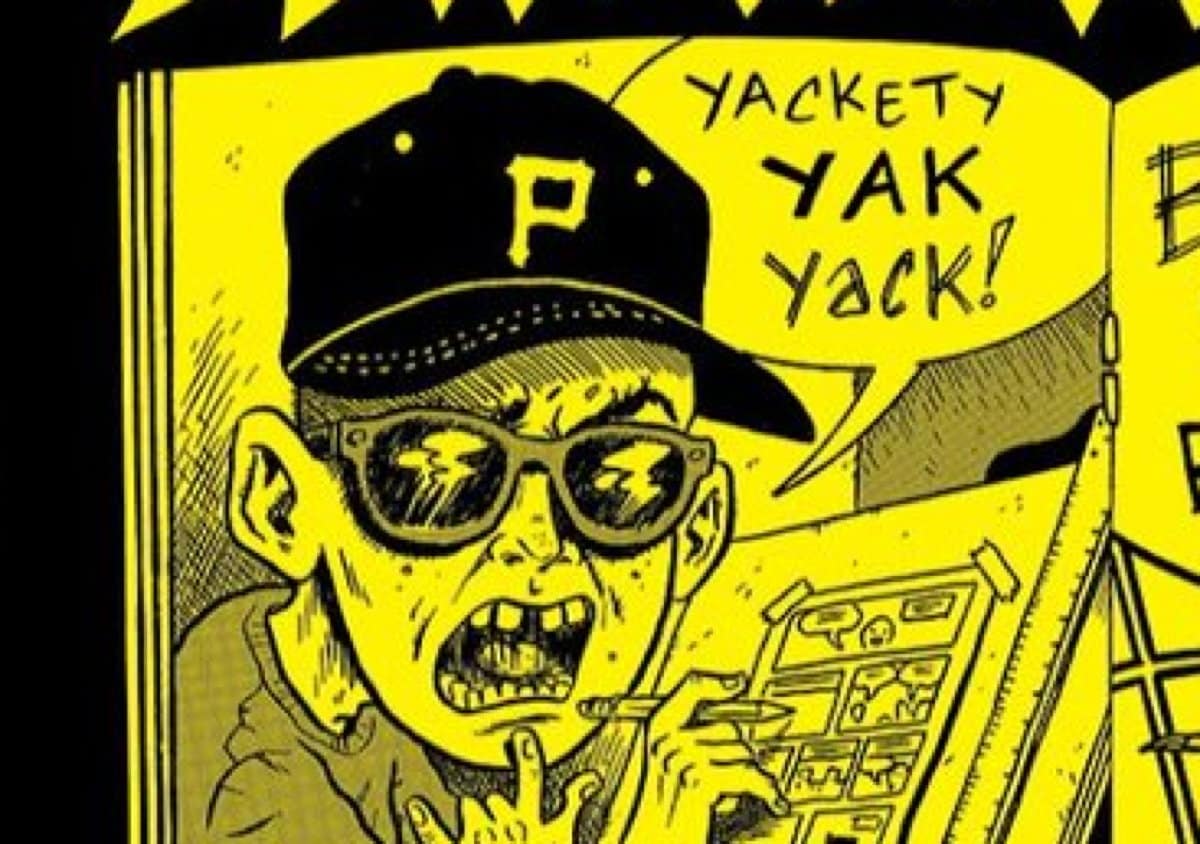

[Photo courtesy of SPX]

By Adam McGovern

One of the final panels of SPX 2013 was about fruitful points of departure. “Paying Tribute: Traditions of Style,” hosted by Joe McCulloch and featuring comics re-creators Ed Piskor, Jim Rugg, Tom Scioli, Seth and R. Sikoryak, navigated the spacetime crossovers and dimensional leaps of writer-artists who assemble new directions for the medium by reassembling past sources within and references beyond comics.

Known for specific quotations of midcentury mainstream comics and the production processes that became famous as their aesthetic palette, Scioli and Piskor spoke about the vocabulary that spoke to them in their earliest engagement with the artform.

Contemporary graphic novels that confront social issue and explore inner identities are “great,” said Piskor, “but it’s not what got me interested in the form.” His new Hip Hop Family Tree book from Fantagraphics is “gonna be an unapologetic comic book,” with all the foregrounded exposition and prominent ben-day particles that this description implies in the public imagination.

Scioli, known as Jack Kirby emulator par excellence, said that, when he first selected that stylistic course, he felt he was “tapping into some old knowledge that needed to seep back into the conversation” — at a time (the 1990s) when comics had a slick process and commercial sheen that had nothing to do with Kirby’s pop-art eccentricities.

Now, of course, all panelists acknowledged that nothing “no longer exists,” with instant and endless access to the history of artistic expression available online.

“Everything you’ve ever heard of you can now find reference for,” remarked Rugg, known for his fluency in multiple pulp-art languages from giant-monster throwdowns to romance-comic melodrama. Scioli welcomed that abundance and considered it an unprecedented popular education for today’s cartoonists, accelerating the sophistication of those now coming up and expanding the knowledge base and expressive possibilities of those who have been at it longer. “I feel like I was doing pop-songs before and now can do symphonies” of influence and reference, he said.

Seth, on the other hands, famous for his focus on art-deco-era succinctness of design, lamented that, with so much imagery available, “they all have exactly the same cultural weight,” and the experience does not lend itself to absorbing these references’ lessons. “Small doses” would work better, he said, and at one time were almost obligatory, as enthusiasts would unearth one old Krazy Kat newspaper page at a time rather than being able to binge on them in large compendiums.

Scioli agreed that, pre-internet, “you had to earn the knowledge,” though he still felt that the range of options leads to an informed “choice between aesthetics.”

A pioneer in the pure application of this is Sikoryak, who has chosen practically every aesthetic but his own, in astoundingly resourceful remixes of vintage comic styles applied to condensed transformations of literary classics. “I try to suppress and oppose any of my own instincts,” he said, likening his process to composer John Cage. “He wanted to be surprised by what he created, not have his tastes get in the way. [It’s about] being faithful to these sources and seeing where that takes me.”

Process, guided by specific inspirations but set up to go in surprising directions, was a concern of all the panelists. Seth spoke of the “subliminal choices” he makes in assembling his reference points; “You start on the work and the work shapes itself.” Rugg’s related interest in reclaiming past stylistic approaches was to have “a chance to try and understand better how these styles function.” Piskor referred to the very imperfections of older commercial comics as a conceptual canvas for his work; “the yellowed newsprint is like an underpainting,” he remarked.

Rugg added that he has been experimenting with photographing his art since he is unsatisfied with the perfection of the scanned digital image; regardless of their dialogue with preceding sources, all the panelists have given thought to what effect it will have on their work when it, too, inevitably ends up as widely recontextualized digital images. Their attitude toward this ranged from Scioli saying he now tries to compose his comics “unbreakably” so they could work on page or large screen or personal device, to Seth being unsure how well his precisely-plotted compositions will fare in unplanned electronic environments.

All, however, understood that this process is unavoidable, and Rugg provided as fitting an epigram as any in his resolve not to think about “what I can’t control.” Information wants not to be controlled, and as these creators show, inspiration can’t be predicted — which, in the artform’s future as on this panel, is more than half the fun.

if only the panel had been recorded…

I think it was filmed, @john siuntres, so check back every now and again at the SPX site; not sure how long it is ’til each year-that-was goes up though.

Comments are closed.