By Matthew Jent

Friday morning, thoughts of weird love and doomed romance took over room 28 of San Diego Comic Con. Moderator Douglas Wolk was joined by author Michelle Nolan and Colleen Coover for a discussion on the Strange Disappearance of Romance Comics.

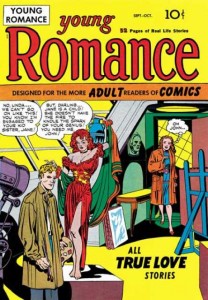

Wolk offered a quick walkthrough of the romance genre’s past. First appearing with Joe Simon and Jack Kirby’s Young Romance in 1947, the last original, non-reprint romance comic was Young Love #126 in 1977. Romance comics were part of the post-war comics boom of the late-1940s and early-1950s that saw superheroes become passé and monsters, westerns, humor, and nearly any other genre under the sun pick up the slack. In 1950, there were more than 150 different and distinct romance comics published every month.

Romance, Wolk explained, is the only genre that has never bounced back.

Why not? A lot of the reason has to do with how timely romance comics were. They were always products of their time period, aimed at an audience of 11 to 13 year old girls, and reflecting current styles in fashion and youth culture.

“Romance comics always paralleled the current and popular culture,” explained Michelle Nolan, author of Love on the Racks: A History of American Romance Comics. “They paralleled every genre. There were crime stories and western romances. In the 50s, there were a ton of Korean War romance stories — stories like “G.I. War Brides” or “I Was a Commie Girlfriend.”

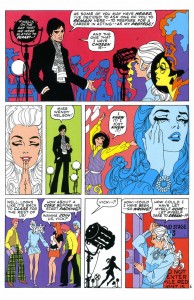

In the 1960s, romance comics looked to popular music, but only when trends reached their pre-teen audience. Marvel’s My Love featured an issue set at Woodstock, but only after the Woodstock movie was released. But even with girls in mind as their audience (and even the ads were geared toward girls, focusing on diet supplements, clothing, and jewelry), the comics themselves were written and drawn by men.

“There weren’t a lot of women working in comics,” said Michelle. “Flo Steinberg was the epitome of women in comics, and she was Stan Lee’s administrative assistant. They were all written by middle-aged men, who used their teenage daughters as inspiration.”

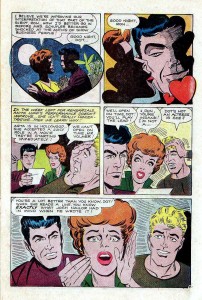

With the rise of women’s lib and feminism in the 1960s and 70s, the tone set by most romance comics finally fell behind the times. The stories were read by young women, written my much older men, featured female characters who were lost (if not outright doomed) until saved by (usually) older, (often) misogynistic, (always) condescending male figures. “With the hindsight of 40 years of feminism, we don’t want comics for girls that are about finding a husband,” said Colleen Coover.

Michelle believes that readers left romance comics because there were more opportunities for love — and sex — in their real lives.

“The one thing that killed romance comics was the birth control pill,” Michelle said. “Most people got married, in the 1940s and 50s, to have sex. Today, people can get all the sex they want.”

More real women in real workplaces also meant the fantasy of romance heroines with exciting careers outside of the house became less of a fantasy. “Nobody has fantasies anymore,” Michelle said. “I want to be a doctor? A female doctor? I can just do it.”

But even if the characters and plots were old fashioned, the art remained ahead of its time. In the genre kicked off by Simon & Kirby, legendary superhero artists like, Jim Aparo, John Buscema, Gene Colan, John Romita, Jim Starling, Alex Toth, and others created covers and interior art that was nothing else in comics at the time. When Roy Lichtenstein copied comics panels for his pop culture art, he chose the most maudlin and clichéd examples he could find. But between the covers of Young Romance, My Love, Young Love, and others, there was truly groundbreaking art being created — which means back issues remain in demand by collectors today.

(Steve Ditko did some romance comics, too, but not a lot. He was “the most inappropriate romance artist,” Colleen Coover explained. “Look at how up and down everything is,” she said, as a particularly uninspired Ditko page was broadcast on the screen. “Everything is perpendicular.”)

By the end of the romance heyday, they were already aiming for the nostalgia market. Comics that had previously been reprinted with updated clothing or hairstyles (or, occasionally, greater diversity of cultures and skin tones) were labeled with a banner that read “Printed the Way Your Mother Read It!” But by the 1980s, with the disappearance of newsstands and the rist of the direct market, there weren’t a lot of comics shops who wanted to carry romance titles, whether your mother read them or not.

“80-90% of comic shop patrons were men, so (romance comics) were limited to mom & pop stores,” Michelle explained. “The big box (grocery) stores didn’t want to carry them — they carried Archie. The newsstand situation also killed romance comics.”

The panel ended with a Q&A. One audience member asked, if books like 50 Shades of Grey are so popular with female audiences, and when romance book publishers occasionally attempt to clumsily translate and market international romance graphic novels, why haven’t mainstream publishers like Marvel and DC revived their romance lines?

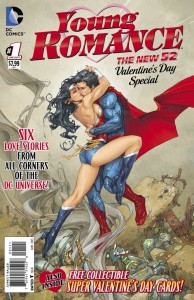

“Economics and corporate identity,” answered Colleen. Those publishers are owned by giant corporations, and the audience that might flock to well written, well illustrated romance comics “is not the market they want. And that’s okay, but — I would love to see Harlequin, or whoever, get a good editor that knows what she’s doing. But if a publisher is going to publish comics that are girl-friendly and aren’t insulting — it’ll be from another source, not Marvel or DC.”

DC’s New 52 did briefly return Young Romance to the stands — but if featured Superman and Wonder Woman embracing on the cover.

The panel agreed that romance comics were unlikely to return from mainstream publishers. Romance parodies will occasionally crop up (such as John Lustig’s Last Kiss, and superhero/romance mashups like Spider-Man Loves Mary Jane will sometimes appear on the schedule, but there simply isn’t an interest, at the corporate and editorial level, for a return to form for the romance genre.

But just as the dinosaurs never really went extinct — they’re all just birds, after all — the descendants of romance comics are alive today.

“Preacher is a really a romance comic,” said Colleen. “Garth Ennis just never told anybody, so he got away with it. A lot of manga has romance in it, but it’s a different narrative structure. A lot of romance comics are on the web, or in queer comics.”

“Queer comics, that’s where the romance is now,” agreed Michelle. “Prism, those are the romance comics today, and straight people can read them and enjoy them.” She directed the audience to check out the Prism booth on the con floor, where they would be happy to tell folks all about their books.

t’s a great point, and it harkens back to what romance comics could do best: subtext. Gay and queer entertainment is still very niche in a lot of mediums, and the chance to create stories about gay characters who are frankly, honestly, and sometimes explicitly, experiencing love, romance, and sex is rare. Comics can be a place where that is allowed to happen.

>> Romance, Wolk explained, is the only genre that has never bounced back.>>

Oh, yeah? Aviation adventure would like a word with you…

kdb

And then there’s the Northern, but that never really was all that well represented in comics. There were some, but not a lot.

kdb

Comments are closed.