When the biographies of so many celebrated male artists are revealed as chronicles self-destruction where the subjects too often allow themselves to become awash in their weakest points, this biography of painter and sculptor Niki de Saint Phalle is refreshing. It’s not only that her story provides a counterpoint to the tortured suffering fetishes presented by the life stories I mentioned, but it’s also because in doing so, it gives ebullience to an already righteous act of revenge. De Saint Phalle’s tale seizes her rightful place in art history despite the misogyny of the gatekeepers of that world, but it also shows that you don’t have to become a victim of your trauma. At the very least, you can try to do your best with it, try to make something constructive out of it.

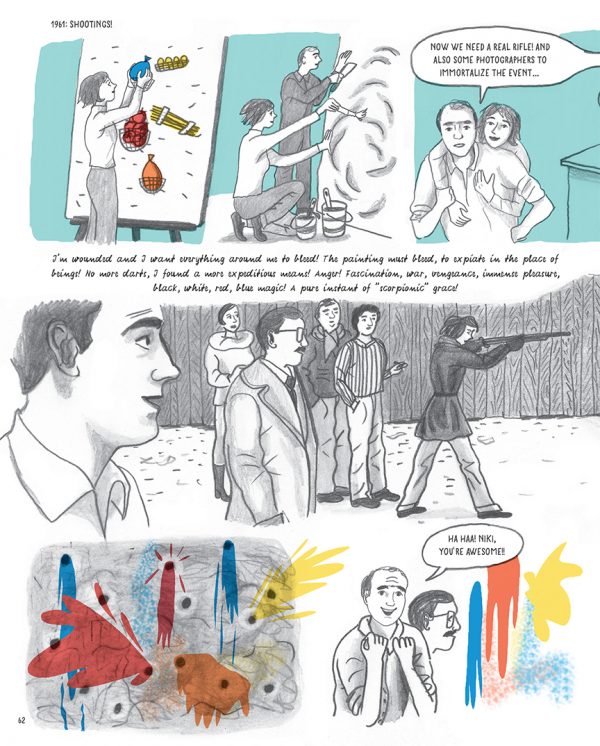

De Saint Phalle is possibly best known for her plump, colorful lady sculptures the “Nanas.” She also gained notoriety for her paintings achieved by aiming a gun and taking shots at the canvas, as well as her walk-in sculptures, which includes one giant woman lying on her back, “Hon,” who viewers enter inside through her vagina.

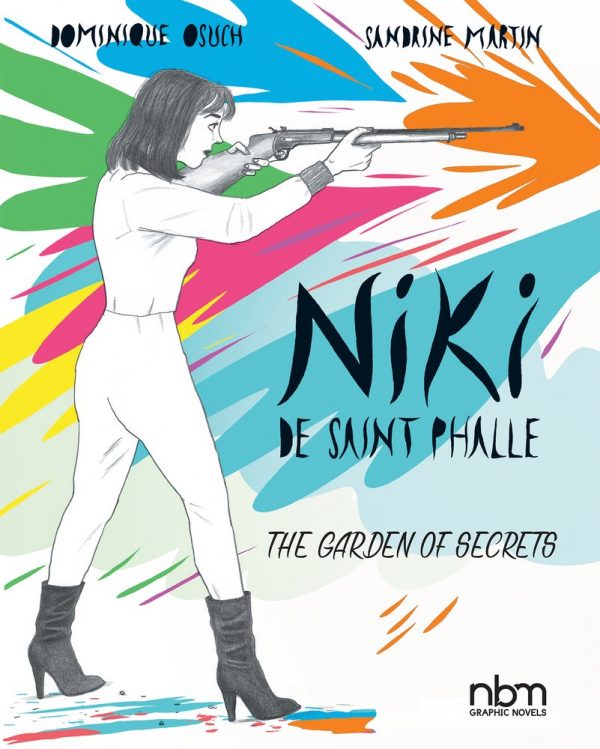

De Saint Phalle is also renowned for her sculpture gardens, the most famous of which is the Tarot Garden in Tuscany. The Tarot Garden provides this biography with its Tarot-based structure and its subtitle, The Garden of Secrets, in which Dominique Osuch and Sandrine Martin allow De Saint Phalle’s life to unfold in a gentle, humanizing fashion.

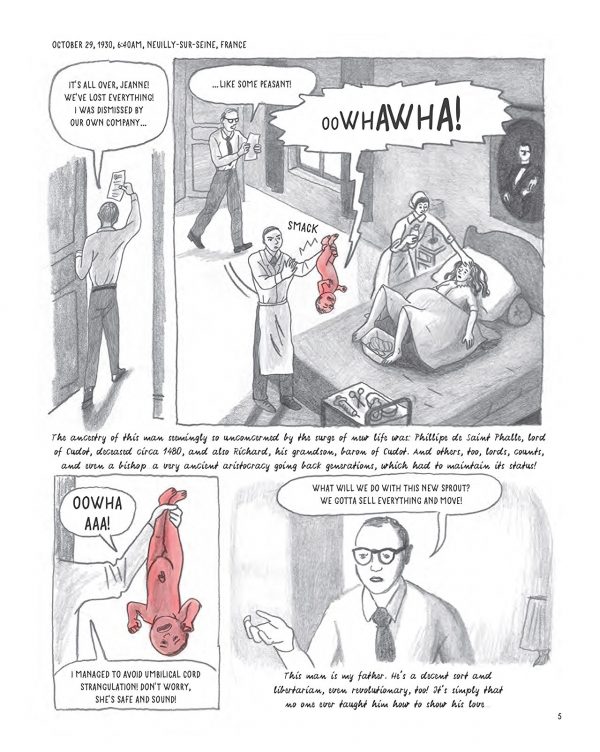

Almost taking the form of a brief diary of events, the biography covers De Saint Phalle’s life from birth to death and gives ample time to her traumas, including an early separation from her mother and molestation by her father. De Saint Phalle’s young adult life brought mental illness and harrowing treatment, as well as a difficulty in navigating parenthood while her artistic abilities unfolded. One gets the sense that this is a person who never knew herself well, or at least had no mechanism to examine herself until art came into her life, and this revelation precluded all other responsibilities out of psychological necessity.

As her life went on, she was beset by health problems that she continually kept at bay so as not to stop her from working, and contained within a cycle of on-again-off-again partnership, both romantic and creative, with Jean Tinguely, who is best remembered for his kinetic sculptures.

In other words, like so many people in the world, hard shit happened to De Saint Phalle, but her strength, alongside her ability to create unique artwork without formal training, was to channel the hard shit and transform it into artwork of immense positivity. But not positivity of a shallow, feel-good variety — De Saint Phalle’s work is of an upward emotion that springs from the depth of her being, often pulling from the people and cultures surrounding her, and reveals itself as a burst of energy out in the world. It is work that is sometimes born of despair but is seldom despairing. Even in its darker aspects, it offers hope.

And that’s what Osuch and Martin match in their biography. With personable illustrative work that tempts you to enter De Saint Phalle’s world, and an amiable, sometimes casual narrative delivery that makes you feel more a part of the biography than an outside observer, Niki de Saint Phalle: The Garden of Secrets reveals De Saint Phalle and her work together as inseparable from each other, as well as the life they both inhabited, and makes an important mark in our art history knowledge while doing so.

She also made a wonderful perfume, which I bought in Paris for my wife. And visit her gardens (Queen Califia’s Magical Circle) in Escondido near San Diego.

Comments are closed.