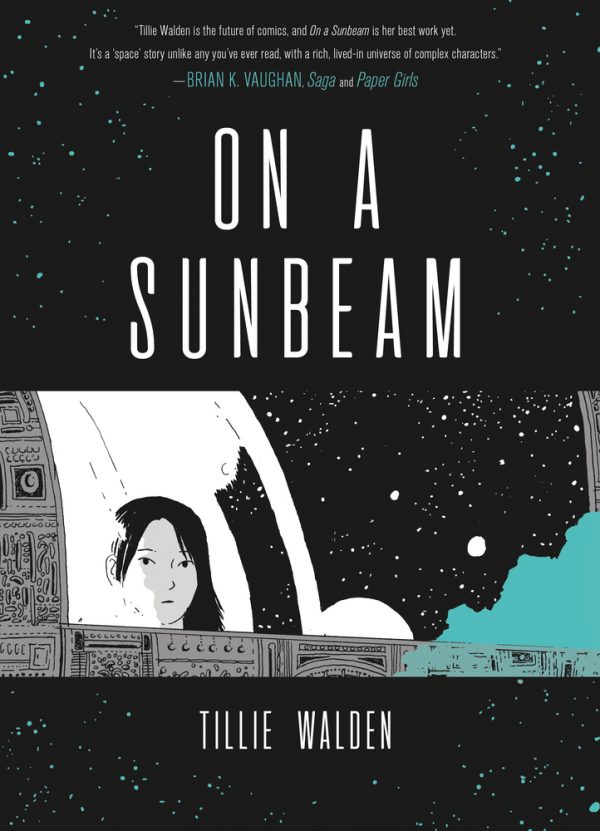

The past is filled with unresolved issues, incidents, relationships for most people, and in many ways Tillie Walden’s On A Sunbeam is about moving forward to work on what’s past.

It’s apt that this is a science fiction adventure, but while storywise it concerns itself with space travel, time travel is just as crucial to the action and emotion it portrays. We all do some time traveling when it comes to the unresolved past. It haunts us and provides us vivid recall that can place us back in the moment of loss and regret. But in our own lives, we also move spatially forward, and emotionally, but also biologically. We grow, our bodies and brains change, and sometimes in such a way that we become more equipped to heal the scars of the past.

On A Sunbeam was originally a webcomic, but this new edition from First Second doesn’t feel that way at all. There’s no serialized aspect about the work, it doesn’t feel dispensed in bits, but rather a smooth, whole novel where the themes stretch back and forth within itself, and the action glides in a continuous forward movement that carries the emotions consistently over its 500 pages.

Mia has signed onboard a crew that travels around space renovating damages structures, and here Walden dispenses with the tropes of a newbie among an established team to establish the emotional tone of the cast — helpful, nurturing, but not without rough edges. Mia struggles with some of the work and makes a significant mess-up, but the members of the crew do their best to straddle the line of patience and acting responsibly that is required for the job.

But Mia has a story of her own, and it unfolds in flashbacks that divide up the narrative as we put the pieces together of who Mia is now and who she used to be. As a student in a private school in outer space, Mia bonded with shy student Grace. This developed into a relationship that continues to loom in Mia’s heart and mind like a ghost beckoning her. The connection between them, and the subsequent disconnection — I’ll keep it at that for spoiler’s sake — left Mia in a position of moving on without completely understanding what she was moving on from. Her work on the ship is just one more iteration of the classic literary trope of getting lost in strange worlds as a way of forgetting.

But Mia, as you can expect, does not forget, and circumstances come together in such a way that she can do something about that. What’s unexpected is that other people have their own ghosts, and helping Mia with hers becomes a way to confront their own.

The real star of the book, though, is Walden’s artwork. She renders space stations and spaceships and alien planets as with any other science fiction comic, but she does so with a sense of mystery and style that I haven’t seen presented equally in any other work. Her technology is organic, almost biological, her star systems and planets misty and ethereal, bursting with the love of her subject matter more than any cold realism. Visually, this book is a tour de force, and I think lots of artists approaching science fiction subject matter could learn much from Walden’s presentation.

I also want to say a little bit about the gender politics of the book, which I found exciting. I have a feeling this is the sort of thing that causes eye-rolling in certain circles, but the book has no male characters, and Walden has designed her reality to move perfectly logically and beautifully without them. This created some tonal and thematic differences from the traditional male-driven science fiction epics within the drama and the action that were fascinating to examine. We have current instances of great female-driven science fiction that provide significant contrasts — Jodie Whitaker’s tenure as the Doctor being a prime example — but I think Walden does something important here by clearing the room of males and giving space to other concepts.

In some ways it’s a brave move, considering a toxic portion of fandom that approaches these things rigidly, and therefore in a backward way, but surely science fiction is a great place to explore these issues. It’s a genre of possibilities, and the way that Walden has chosen to explore those is not only solidly within the history of the genre itself but has also given her the opportunity to yield an accessible tour de force.

Comments are closed.