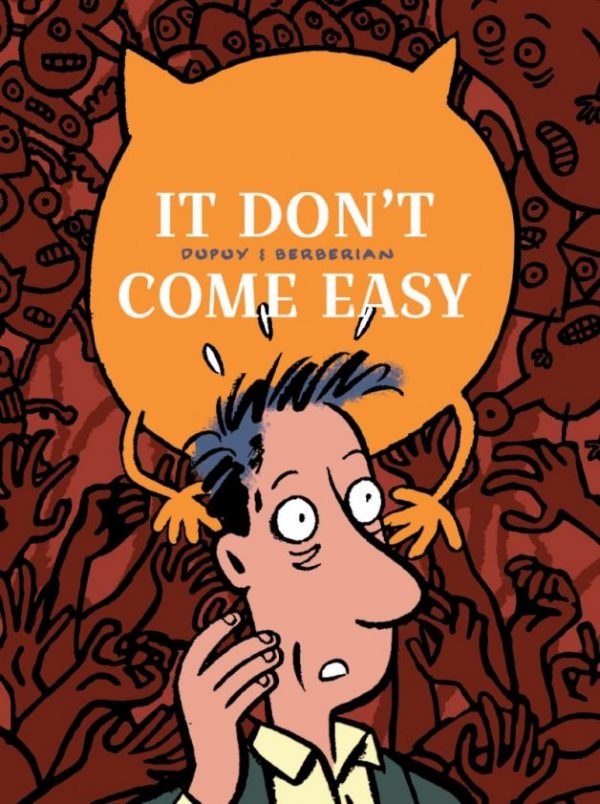

The Angouleme-winning Monsieur Jean series by Philippe Dupuy and Charles Berberian is celebrated here with It Don’t Come Easy, a collection of some of the latter-day stories in the series, a grouping that covers Jean’s settling down and finds other characters in the cast doing some semblance of the same.

These stories often get compared to the work of Woody Allen, but I’d dispute that — Jean is likable, for one, and the relationships surrounding him aren’t set up as antagonistic. Even those with some disagreement are at their root well-meaning and defined by a fondness between the characters. And, of course, Jean is not self-absorbed to the degree that it is a weapon against the people around him. Jean is far less Woody Allen than a fumbling everyman with positive intentions, comparable to Michel Rabagliati’s Paul character.

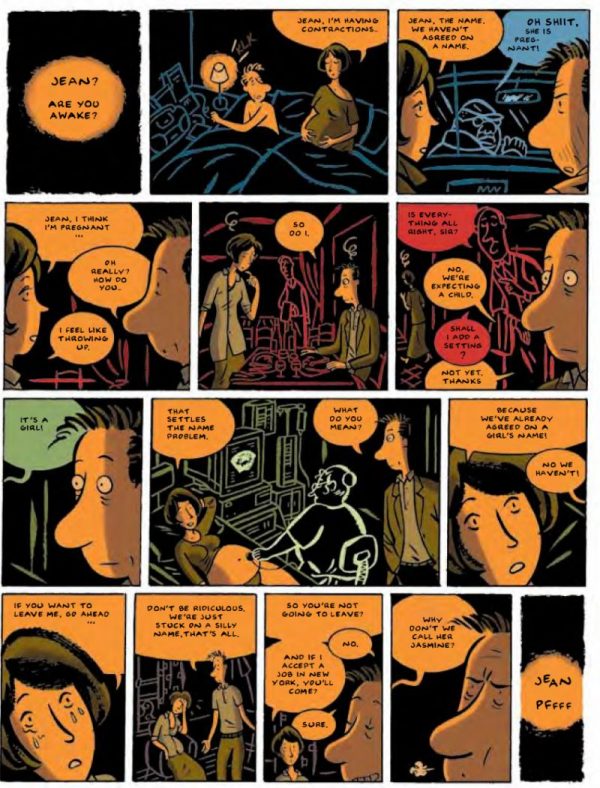

The first story in the book is thematically framed by the telling of a Japanese fairy tale about an enchanted fish, though I’m not clear that it’s an actual fairy tale. It’s a love story about a fish that becomes a beautiful woman, but it’s also the story of emotional neglect, of taking things for granted. It’s central to the story of Jean and his girlfriend, Cathy, as they try to work out their status, which forms the narrative backbone of this collection.

Jean lives with Felix who has an adopted son, Eugene, the child of his ex-girlfriend. Felix is unreliable, and Jean ends up as Eugene’s caretaker a lot of the time. It’s not necessarily how Jean wants to spend his time, but he typically cleans up Felix’s mess because someone has to go out of their way for Eugene. Together, they go to the wedding of old friends — they are re-marrying — and Jean has to negotiate that relationship in the context of his relationship problems and his stewardship of Eugene, a victim of a fractured, impossible-to-mend relationship.

In this telling, splits brought about by emotional distance seem inevitable, par for the course in relationships, and Jean’s challenge is to move beyond the normal and conceive of the mechanism his relationship with Cathy as something not to be settled for but strived for.

We get answers immediately in the second story, which finds Jean and Cathy in New York City with a daughter, Julie. Jean is bringing Julie to Paris for a visit, but old patterns take over, and Jean is smothered in Felix’s problems, as custody of Eugene becomes very iffy. These two situations smash together for a solution that is both absurd and poignant but also appears to move Jean forward.

The third story finds Jean at a time of transition partly in the context of maturity, but especially regarding the simple feat of moving forward. Part of this involves resisting too much entanglement with Felix, but much of it is that challenge of letting go — that is, discarding much-needed sentiment as it weighs you down. One problem is that after moving into a new apartment, Jean becomes attached to a box of belongings left by the previous resident, obsessed with the idea that he somehow owes it to the man as a way of keeping his memory alive.

At the same time, Jean is haunted by the bickering ghosts of his parents as they harangue him about giving their bed to Felix. This story is filled with interludes from reality, not only with Jean’s parents but dream-like sequences that become more extended and culminate in a nightmarish premonition of destruction and Hell.

The fourth section is a collection of much shorter pieces, mostly single page bits that can best be described as intellectual gag strips. Coming after the complex, sometimes intense, first three stories, much of this material feels a bit like throwaways — not that they are bad, not at all, but the tidbit quality has them functioning like brief bullets that make their points more directly instead of inviting complex character actions and reader understandings.

Dupuy and Berberian’s portrayal of these light dramas unfolds in that expressive, cartoonish European art style that functions as urbane and emotional at the same time. They manage to create characters who aren’t caricatures at all, but who are defined by their types as illustrated. They transcend the presentation in the dream sequences, though, where the style gets darker, more menacing, and cartoonish quality struggles not to be overtaken by the fear that attempts to overwhelm the lightness. It’s a compelling portrayal of the harder parts of Jean’s psyche.

That’s where the real power of the work comes in — the hard parts are always there, but Jean and cast are used as buffers to keep the drama from becoming too overwhelming for the reader. And that’s more like actual life anyhow. Tragedies come and go, but absurdity reigns and keeps the worst at bay — more often than not, anyhow. Darkness and light intertwine to create the reality lived.