We all have things we’d like to explain to our teenage selves, and I have a feeling the older we get, the more we want to unload. But there are levels of knowledge that can be addressed depending on your life. The necessary conversation might entail professional or educational advice. It might touch on family relationships. It might delve into romantic relationships. But what if the conversation is so big that is revolves around who you are — who you were and who you became? And what if those were directly linked to secrets and shame?

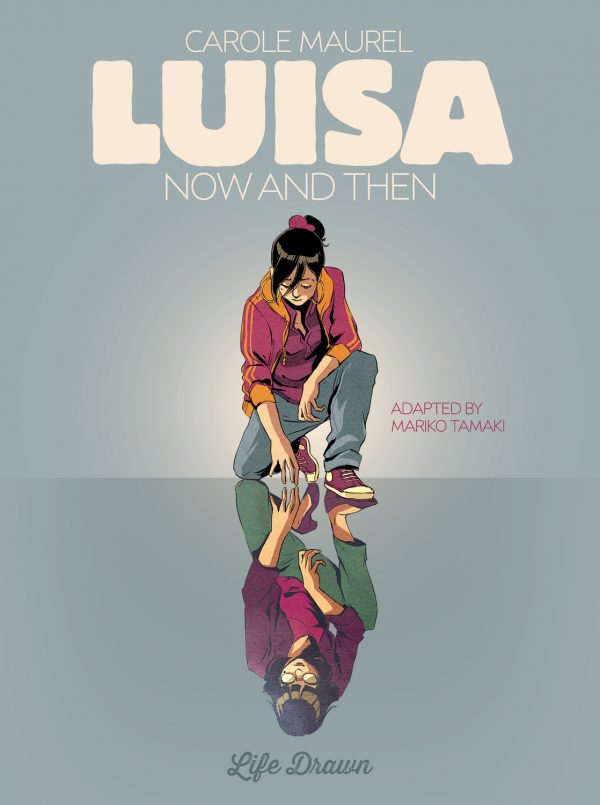

In Mariko Tamaki’s English-language adaptation of French cartoonist Carole Maurel’s Luisa: Now and Then, it’s all those things boiled down to the most basic of truths, the one about who you love. For 32-year-old Luisa, the answer to who she is and who she loves is a disheveled heap of confusion at best, but the core of what and why becomes more clear as she confronts herself in a very literal way.

Luisa is about to meet herself as a teenager who is still figuring it all out, but the point is that Luisa only pretends to have figured it out. Privately, she admits that not quite the case, but she hasn’t the ability to step back to the roots of her anguish. That is forced on her with the arrival of her teenage self, who steps off the bus one day, finds herself in the future and makes her way to her aunt’s apartment trying to find her way back home. It’s the future, though — her aunt is dead and grown-up Luisa lives in the apartment instead.

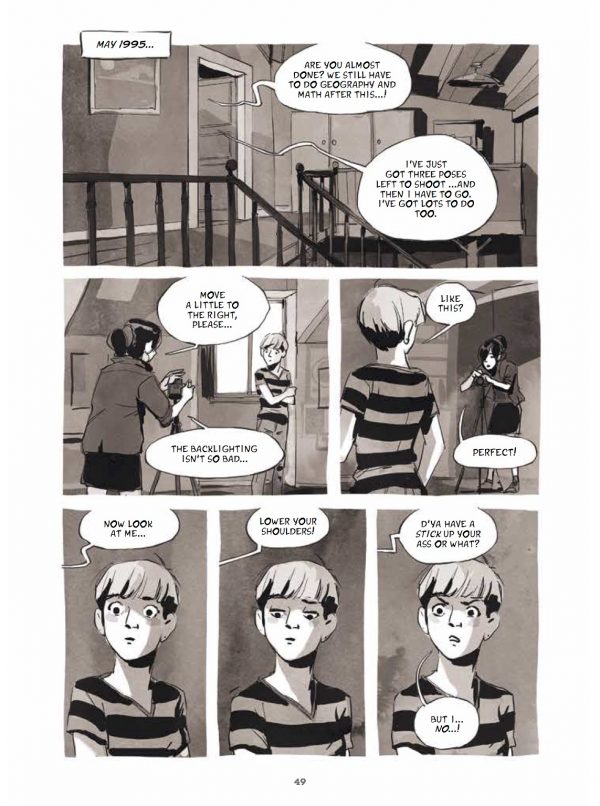

Tamaki and Maurel focus mostly on the present meeting but takes a few divergent shifts to the past where we see Luisa’s friendship with Lucy fall apart in an assault of hate from Luisa’s other friends. Lucy is gay and Luisa’s friends’ hateful and upsetting homophobic rant drive Lucy away, this after a kiss between Luisa and Lucy answers questions that have stirred in Luisa, but shame prevents her from accepting the moment.

Jet ahead and Luisa’s life is a direct reaction to the shame she felt that day, and especially the fear of rejection by her family and the hate that other kids in the neighborhood felt about same-sex relationships.

Tamaki and Maurel manage to take such heavy soul-searching into a sometimes comedic realm, especially parts involving Luisa’s neighbor, a gay musician who resembles Lucy and is bonding with young Luisa. But it’s also a work of tender soul searching and honest dialogue that does well in addressing its central concerns as well as more general concepts of growth and change. It’s an excellent balance that allows it to speak to those who face Luisa’s situation themselves — either as a teen or as the adult who represses the pain — and to those of us who haven’t been in that specific situation.

For that latter category of reader, it builds sympathy and understanding for a specific situation that is outside of our personal one. But regret, fear, repression, hurt, find many ways to attack you in life, and are quite skillful at hanging on for years and years. The longer you try to ignore them, the more damaging their grip becomes, until such point that they are invisible and the forces that have destroyed you are just part of what you feel is normal.

In context of Luisa’s story, this means something that is at her core and can make herself whole in regard to how she connects and bonds with other human beings, and how love is expressed. A solitary, alienated emotional existence that has dragged on for years can finally begin exploring its real self, and anyone who reads this charming story might be able to see in themselves or in others they know a fuller picture of who anyone can be if they are just allowed to express all parts of themselves.