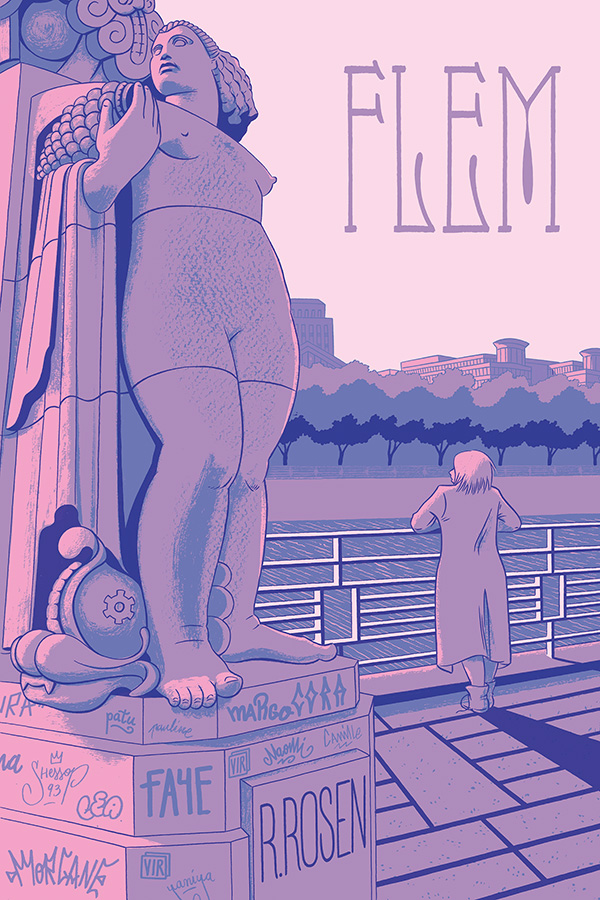

Brussels-based and Montreal-born cartoonist R. Rosen makes her graphic novel debut with Flem, a tale of psychological distress, self-destruction, and political activism that casts a sympathetic view towards all three, but not without a dose of reality.

Julia Maarten is an art student and she’s falling apart. She can’t quite rise to the occasion in her classes — her work is falling flat under the weight of her disenfranchised approach to creating art. A rare night out with a friend introduces her to a feminist collective performance group who at first appears to be the answers to her lack of passion, but might instead be a form of escape that proves itself incapable of providing the nurturing Julia needs.

There’s plenty that Julia is trying to escape, but at the center of it all is her mother. A lifelong sufferer of mental illness, Julia’s mother is alternately pushing her away and clinging to her much too tightly, inserting guilt trips into whichever stance she takes and creating a flight reflex in her daughter. But while the mother bemoans the psychological problems she passed along to her daughter genetically, she’s incapable of looking at the nurture alternative to nature and seeing how aspects of her behavior she could do something about also hurt her daughter. Julia’s inner demons find their expression in outer terms through drink and drugs and, most overtly, obsessive nose picking that is making a sore get worse and causing more and more nasal bleeding.

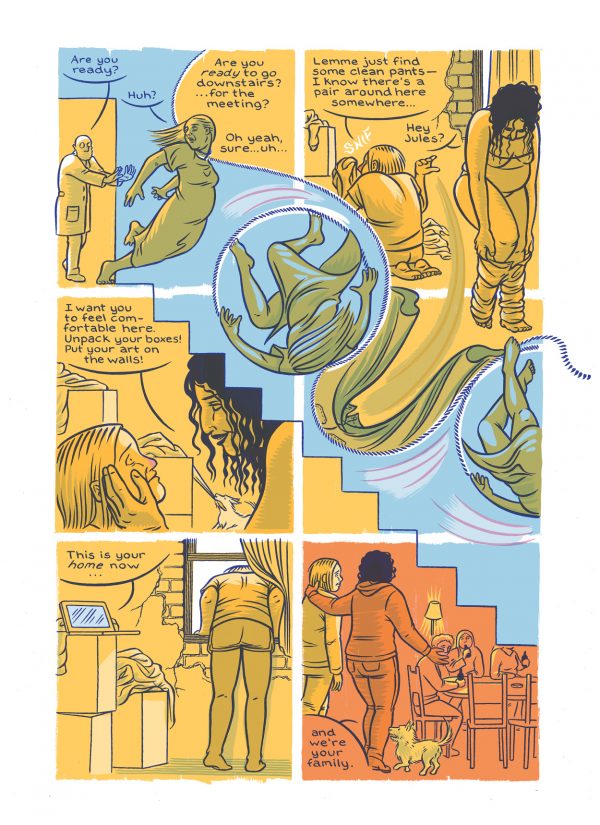

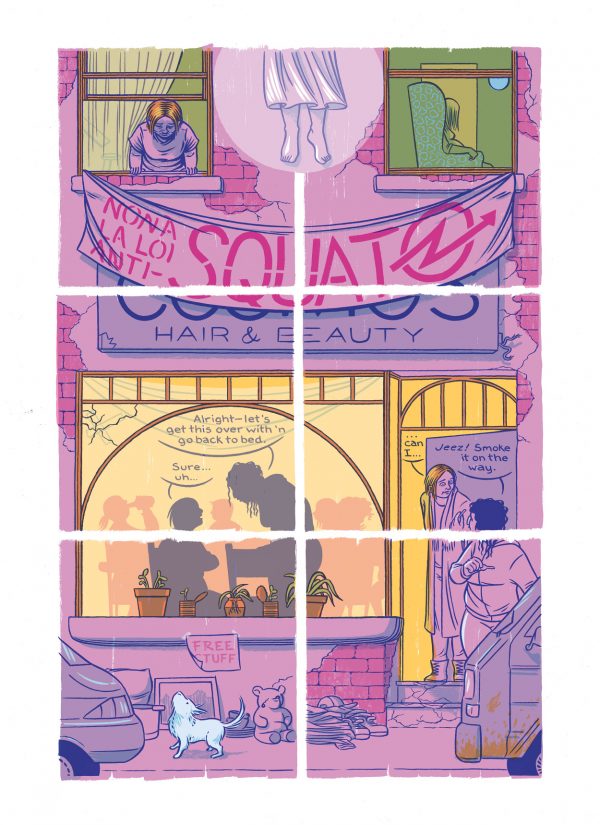

For Julia, it becomes a descent into replacing what she is missing — structure and authority, as well as honest and loving emotional support — within the context of a political art collective functioning in a squat, which is as absurd as it sounds. But by entering into a relationship with one of the women, and therefore shifting the domineering girlfriend and the rest of the collective into an authority position, Julia finds something to rebel against again, coming full-circle with her parent-replacement and conjuring a reason to self-destruct further. And the collective, focused on their own political goals, has trouble negotiating a member’s personal problems. It doesn’t get better from there.

If Rosen’s work here seems a little depressing, it’s in service of a wider scope on the subject matter. Rather than focus on the hurt of the broken person solely from the point of view of that person, Rosen portrays the different parts of that person’s life that contribute to her downfall or sometimes fail to intervene in a meaningful way. It’s a litany of what can only be described as micro-aggressions — micro-failures? — within contexts of relationships that are generally perceived to be empowering.

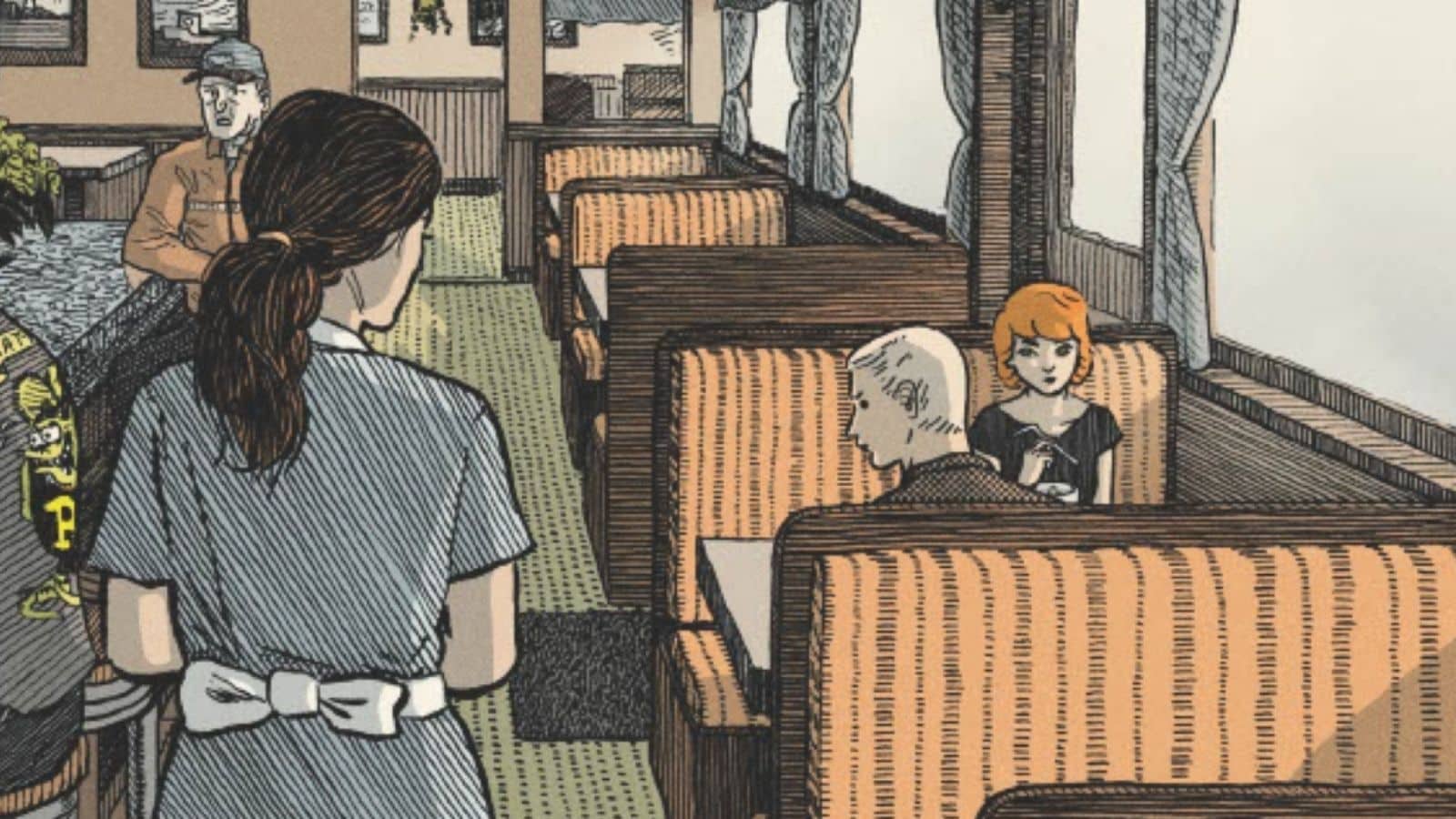

The feminist collective, in particular, is portrayed as a passionate place, but also distant, unfulfilling beyond the political goals. In one crucial scene, the group sits at a table to discuss plans while Julia drinks a beer, knowing she is not supposed to. Rather than express concern for Julia’s behavior, for the incident as an example of her compulsion to act out her pain and drag herself down in front of other people, it’s snippily expressed that the table is “supposed to be a sober space” by Julia’s girlfriend, with no recognition of why Julia would ignore that rule.

There’s little hope offered in Flem, but Rosen is able to express such darkness with her beautiful, vivid color arrangements that offer a truly surreal and unhinged perspective on the world she walks within, leading to a final frenzy of incoherence that Rosen is able to bring back to focus briefly, just enough to provide no closure at all, much like life sometimes.