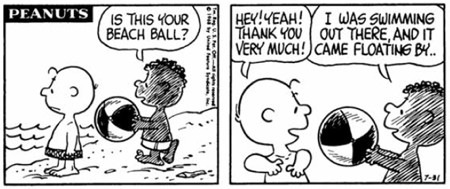

Here’s a window into comics as social history as Nat Gertler write about this history of Franklin, the black kid in Peanuts which began with a request from a white schoolteacher named Harriet Glickman in 1968:

That request earned a personal reply from Schulz, who noted that such ideas had been discussed with fellow cartoonists, but that they were afraid that such character introductions would be seen as “patronizing our Negro friends.” Glickman seized on the apparent desire of Schulz to get past that point and sought his permission to run the concept past some of her own “Negro friends.” Schulz was eager to hear what their thoughts would be, but confessed that “the more I think of the problem, the more I am convinced it would be wrong to do so.” (Schulz was hardly alone in his reluctance. Glickman entered into a longer correspondence with Allen Saunders, then-writer of Mary Worth, who noted that the strip had formerly included black characters in supporting roles, generally doing menial work but depicted with dignity. He explained to her that “it is still impossible to put a Negro in a role of high professional importance and have the reader accept it as valid. And the militant Negro will not accept any member of his race now in any of the more humble roles in which we now regularly show whites. He too would be hostile and try to eliminate our product.”)

While such overt fretting and fussing might seem ludicrous today…it really wasn’t, given recent history. It did turn out that Franklin was a pretty bland character:

Perhaps due to excessive caution, Franklin was never granted any of the sort of usual quirks that define a Peanuts character, the very sort of mistake that Glickman was warning about when she called for one of the black kids to be “a Lucy.” Schulz may have had more to work with if he had listened to Bishop James P. Shannon, who had marched beside Martin Luther King in Selma; Shannon was quoted in the Los Angeles Times as wondering if the new Peanuts character would be “a believable human being who has some evident personal failing,” versus being “a perfect little black man.”

While its sad that a creator of Schulz’s caliber fell victim to tokenism, at least he tried to be inclusive.

I’m reminded, of course, of South Park’s character, Token Black:

Token is the only black kid in town, but a regular part of the supporting cast, albeit without too many distinguishing features from the rest of the kids—although he does find Tyler Perry funny, alone among the kids in town.

Finding Tyler Perry funny is a pretty evident personal failing.

Hmmm… isn’t Franklin the only character in Peanuts who DOESN’T have some sort of quirk?

Geez… Think about it… Charlie Brown’s neighborhood is kinda strange!

http://peanuts.wikia.com/wiki/555_95472

Torsten:

Frankly wasn’t really the only character without a quirk. Characters like Shermy and Patty did not have particular quirks; Patty had an abrasiveness that was basically default for the female Peanuts characters from the first half of the strip’s run. Shermy was a boy who did basic boy things. Unsurprisingly, however, they faded out of the strip, as the cast grew and they rarely had anything specific to contribute.

(As to whether Franklin is in Charlie Brown’s neighborhood: he’s not in the immediate neighborhood. He lives in what seems to be an adjacent neighborhood, which is why he doesn’t go to Charlie Brown’s school but rather the school that Peppermint Patty attends.)

(Yes, I get a bit nerdy about Peanuts.)

What quirk does Violet have?

Violet was the prissy one.

Growing up I never saw Franklin as “the black one”, I saw him as the normal one. The proxy for the readers who didn’t carry emotional baggage from their childhoods.

Violet must wear violet colored clothing; that is her quirk.

Comments are closed.