William Kuskin, Ph.D., of the University of Colorado, Boulder, introduced Denver Comic Con’s keynote speaker, cartoonist Chris Ware, as a man who presents “honesty” as an “antidote to the emptiness we see in culture now, countered by art, even if he evokes a nightmare through that honesty”. Ware guided the audience at DCC through the major thematic movements of his life from childhood through his most recent work on Building Stories, closely interwoven at every juncture with his observations and engagement with art. From Ware’s student days, instructed in art school, where he “felt alienated”, that art was essentially dead in modern times, to his early work creating “wordless comics” in student papers, he encountered the realization that reading comics produced “sounds in his mind like music” and struggled to understand that phenomenon.

Ware spoke very favorably of his work with Fantagraphics beginning in 1993, a time when he was allowed a great deal of freedom to create an “intimate relationship with a book” for readers in terms of format, design, and content, and explained how proud he was to produce the hardcover of Acme Novelty Library at a time when there “weren’t that many hardcover fiction comics”. During this period Ware began to confront “how the human mind distorts reality and changes expectations”, he said, which “leads to human unhappiness”. Working on McSweeney’s was a time when he hoped to produce, “the best possible example” he could “for intelligent, literary readers” to encounter new work and looked to the example of Raw Magazine, which he felt challenged him to a total design approach in a book.

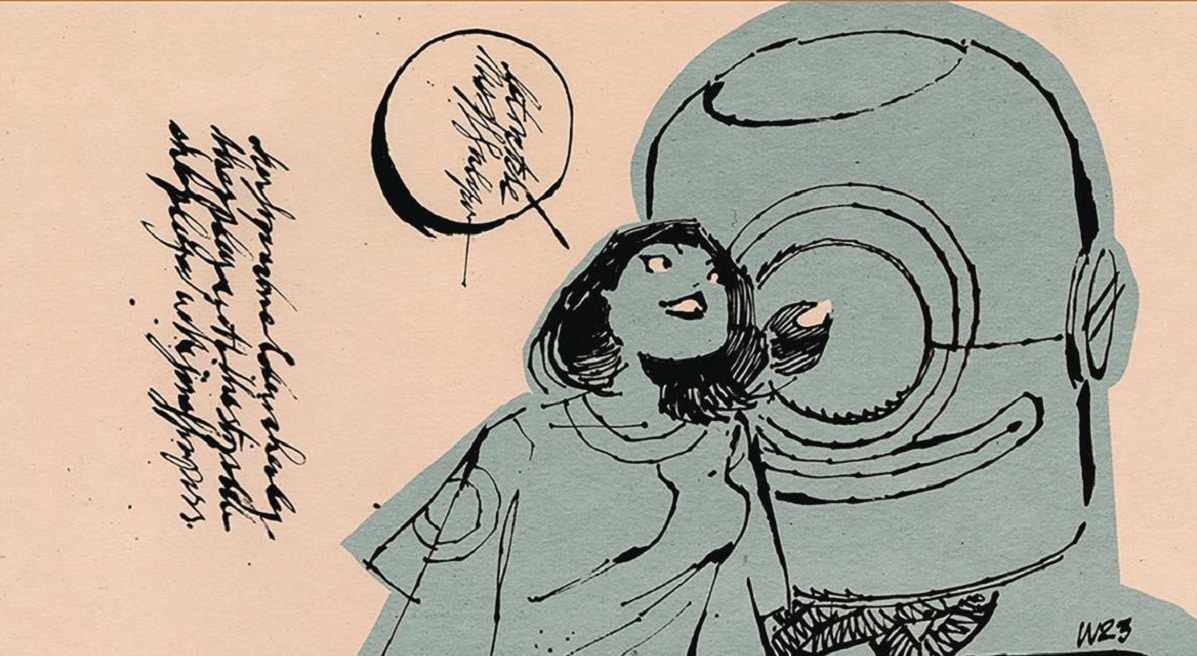

When it came to discussing Building Stories, Ware was keen to delve into art history and the objects that inspired his fascination. From the initial series of “strips” that appeared in an “obscure Swiss magazine”, wordless for practical reasons of translation, following the inhabitants of a Chicago apartment building, to serialization in the New York Times, Building Stories was something that experienced a long period of construction itself. He described Building Stories as a “book about everything” and a work that has led him to especially question “what tense” a comic is composed in, since to Ware, comics exist in the “past and present simultaneously”. He quipped that this should be the next Ph.D. thesis question for scholars. Examining some images from Building Stories also led Ware to comment on the way that times seems to move more and more quickly in life, and from his personal experience, even more so once you have a child. He briefly explained the digital aspect of his related project for Wired Magazine with “touch sensitive interface”, but commented that the project eventually led him to reject digital format since, he said, “I don’t like charging people money for electronic information”.

This single strongly posed challenge to his art education kept him from accepting a defeatist view of modern art production. In closing, Ware treated the DCC audience to a viewing of the animated short Quimby the Mouse, a project geared toward a “potential HBO show that didn’t happen”. The enigmatic but gripping animation, accompanied by music and conveying both slapstick and silent film elements, as well as nods toward early animation, seemed to support Ware’s previous statement that some works can be “incredibly moving” while suggesting emotion but avoiding sentimentality.

Hannah Means-Shannon writes and blogs about comics for TRIP CITY and Sequart.org and is currently working on books about Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore for Sequart. She is @hannahmenzies on Twitter and hannahmenziesblog on WordPress. Find her bio here.

Good coverage!

Chris Ware is one of the best artists ever, in the history of mankind, and just a phenomenally kind human being. I had the pleasure of talking to him once about the effects his work had on me at a difficult time in my life and it lead into a longer discussion on what empathy is. He also gave me some very valuable criticism on my comic work. I’m quite jealous of the people who got to hear him deliver this talk.

I only read one comic by Ware and that was Lint. It was amazing and I can’t wait to read more of his work.

Comments are closed.