§ Multiversity has been killin’ it lately with a bunch of industry analyses and convention reports. Here’s David Harper on Creator-Owned and the Thin Line Between “To Be Continued” and “The End” whch spins out of a comment Brandon Montclare made right here at The Beat.

What that commenter fails to realize, and what Montclare only scrapes the edges of, is that comics exist within a delicate ecosystem. A title’s fate – especially when it is outside of Marvel or DC – can be determined before a single issue is even released, and beyond that initial launch, it takes the actions of readers, retailers and creators in various channels and forms to keep those books alive in an increasingly diverse and competitive market. Those three groups don’t just impact the fate of a book, though. Each group impacts one another in some obvious and some not so obvious ways, and those three work together to create the special alchemy that makes the wheels of the comic book industry turn.

§ New Yorker cartoon editor Robert Mankoff remembers Charles Barsotti who passed away on Monday.

§ Cleaning up the tabs, a few days ago Beat alum Marc-Oliver Frisch took on comics criticism with a piece called What We Talk About When We Talk About Crit, which, in my sleep deprived state, was a hard slog for me:

It may well be true that people view criticism “as an extension of the artistic experience,” as Tom Spurgeon suggests. It’s probably fair to say, too, that “criticism” tends to be seen as being synonymous with “reviews,” and those, in turn, as a service rendered to the entertainment seeker—plot summary, some light background info, thumbs-up/thumbs-down recommendation, mission accomplished. Consequently, the worst and most obnoxious thing a critic could possibly do is be a spoilsport, either by being ambivalent, or by revealing plot points people would rather find out themselves, or by suggesting their taste is superior to the taste of their readers. It’s no wonder critics aren’t terribly popular when, at best, they’re supposed to be glorified food tasters, efficient catalysts for a maximized entertainment and/or artistic experience, ideally with no delusions of being anything more than, at best, useful leeches.

§ Sort of along the same lines, Dan Nadel interviewed Hillary Chute, an academic who is best known for her books of interviews with comics creators, Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics this year’s Outside the Box: Interviews with Contemporary Cartoonists, and as the organizer of the famed G17 2012 cartoonists summit, Comics: Philosophy and Practice. Nadel stats off with some sharp questioning on whether Chute has been making a canon, and why she doesn’t include cartoonists such as Mat Brinkman, Ron Rege, CF and Ben Jones in her interview series, considering many of her actual subjects were interviewed or profiled in previous books about cartoonists. (For the record the cartoonists in her latest book are McCloud, Burns, Barry, Kominsky-Crumb, Clowes, Gloeckner, Sacco, Bechdel, Mouly, Tomine Spiegelman and Ware—a group certainly not encumbered by obscurity to be sure, but they are pretty much the best of the lot from the last 40 years or so, so they earned it.) Anyway, Chute replies:

I don’t think the Comics: Philosophy & Practice conference or Outside the Box ignores post-2000 developments in comics–almost every single person I cover in Outside the Box has published a really important recent work, like Charles Burns’s The Hive, Chris Ware’s Building Stories, Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, Lynda Barry’s collage activity books, and Phoebe Gloeckner’s in-progress reportage on Mexico. So it doesn’t seem backwards looking at all: these people are doing fascinating and game-changing work right now.

Setting aside that the cartoonists Nadel is championing are ones he used to publish when he ran Picturebox—being passionate about the creators you publish is a good thing—this harkens back to a matter I’ve touched on here several times: the lack of cartoonists of acknowledged or potential canonical stature since, hm, let’s say Fun Home. Whether this is because they aren’t as good, they don’t have strong enough bodies of work (maybe because they don’t need to publish regularly as everyone listed above did at one point) or the “canon” is locked up tight, I’m not sure. Or maybe Frisch is right and writing criticism is such a hopeless task that we just let the chickens run free in the barnyard now. And you know, I’m not in favor of “canon” either. But I’d join in on what Chute suggests Nadel’s agenda is: if there is a canon, the Hernandez Brothers need to be in it.

Nadel linked to the current, comic-focused issue of Art- Forum, where more of this argument turns into a catnip toy for kittenish commentators. A few have been posted. One such is disreputable sources: art and comics by Fabrice Stroun, director of Kunsthalle Bern, who argues that since going mainstream, comics just aren’t as edgy and cool:

OVER THE YEARS, Artforum has published reviews of all types—laudatory or excoriating, lyrical or polemical—but only one has taken the form of a comic. That singular piece, authored by Art Spiegelman, appeared in the December 1990 issue of the magazine. Spiegelman’s task was to assess the controversial exhibition “High and Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture,” which had gone on view the preceding October at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and, while he was not nearly as incensed as some commentators by curators Kirk Varnedoe and Adam Gopnik’s mixture of MoMA masterpieces and pop-cultural detritus, he was by no means complimentary.

Given that this is Artforum, its natural that comics should be approached from the fine arts direction; I haven’t heard the notorious High and Low show referenced much in recent years, but it does hold a kind of Wertham-like stature in the history of comics acceptance, since it was a thorough beat down of the “low” part of the exhibit.

The other night I was chatting with someone in the academic world who told me that although comics are generally accepted in the pop culture sphere, in academia they are still fighting for their place. The cartoonists Chute covers can certainly all be used as rungs on the ladder to High Art; it will be a long time before a C.F. or a Nilson gets to join the club though. (BTW Chute does mention a bunch of younger cartoonists she likes in the piece; to see who click the link!)

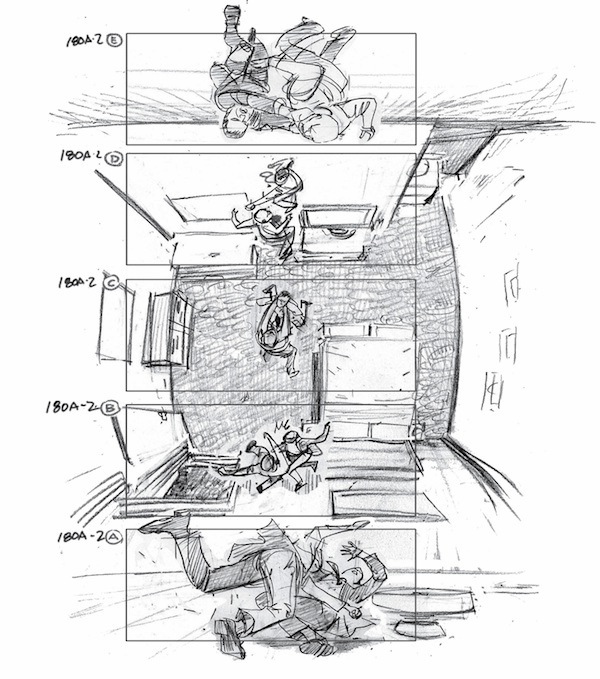

§ New nerd-friendly Nikki Finke has a piece on the odd place of storyboard artists in Hollywood—they’re stuck in the Art Direction union when they probably shouldn’t be. I mention this becuase so many storyboard atists are quasi-cartoonists, or even cartoonsits, like Gabriel Hardman, whose storyboard for Inception is above.

“We board artists are basically stuck (after being forced to integrate) inside a union which has nothing to do with who we are. That’s the gist. Our concerns are not theirs. And secondly, we are not who people think we are. We’re like a white elephant in the room whom nobody wants to address. ‘Hellllloooooo?… is there anybody out there?’ [Pan right to the powers that be as they nervously look the other way.]

There is a new Guardians of the Galaxy trailer with portentous, choir-infused music, sad childhoods and every assurance that this will be just like every other Marvel movie, after all.

titling your book “Contemporary Cartoonists” and not including a single cartoonist under the age of 50 is absurd.

ignoring the Highwater/Kramers Ergot/Fort Thunder crowds now (well over a decade in our rear view mirror) makes as much sense as leaving out the Raw/Weirdo people, not to mention the new breeds out of Canada and cartooning colleges.

if she has simply called the book “Why Yes, These Are Your Father’s Comics”, i doubt anyone would have had a problem.

and Guardians of the Galaxy looks worse with every new trailer.

OK, so canon formation. In the academic context, canon is ultimately all about syllabus creation (the canon is what’s taught–or, rather, what one feels one needs to teach to do a defensible job of it). And syllabi are ultimately dependent on what’s in print–photocopying and scanning can mitigate this fact, but only so far. To be in print indefinitely is to be canonical (and here’s where academics and fans and creators meet: if it’s not readily available, it’s not going to be taught/read/ripped off/homaged, etc., etc.)

I suspect this is a reason why the comics canon a la Chute looks as monolithic as it is: it’s comprised primarily of cartoonists who’ve managed to keep their work in print during the period when comics finally broke through at the academic level (and remember that Chute is a professor, analyzing comics from that subculture as much as if not more than fandom). Moreover, many of the creators she focuses on have AFFORDABLE and COMPACT work in print: it’s easy for me to ask students to buy Fun Home, One Hundred Demons, Jimmy Corrigan, and the like. Los Bros? Their in-print record has generally been spottier, their volumes often more expensive. That’s changing now, so I suspect we’ll see them showing up more often (although I still am looking for a teachable way intro their oeuvre).

At what point has Love and Rockets ever been out of print.

In the sense that you can’t buy some substantial portion of it at any one time? Probably not for very long.

But in print in the way that, say, all the majors works of Charles Dickens or Virginia Woolf or Toni Morrison or Ernest Hemingway are in print? Pretty clear to me from a Google search (to back up my own impressions as a long-time frequenter of comic shops) that there have been numerous times when some equally substantial portion of the series has not been in print.

From a practical standpoint then, L&R has not been teachable (and thus effectively canonical as opposed to ideationally canonical) in anything like the way that Maus or Jimmy Corrigan or Persepolis or any of the other usual suspects have been.

Look at it this way, I really want to teach Zap #0 and #1 in my comics class, but that volume of the Complete Crumb is out of print (as least as recently as early May). It’s a bit of a problem that probably the two most influential floppies of the last four decades can’t be bought at an affordable price.

my issue isnt with the cartoonists she selected, or even why.

my issue is with her labeling them “contemporary”.

i’d hate to think that anyone might pick up this book and think they’ve seeing anything remotely close to what contemporary cartooning actually looks like now.

call it “The Living Masters of Cartooning”, or some such.

>>my issue is with her labeling them “contemporary”.>>

If they’re currently working, they’re contemporary cartoonists.

If they’re all over 50, there’s an argument to be made that they’re not fully representative of the contemporary field as a whole. But if they’ve all been releasing new work recently (or are about to, like McCloud), they’re contemporary cartoonists.

kdb

my apologies if i made you (or anyone else) feel old, it was not my intention.

i’m using the art world biennial-esque definition of contemporary, which seem appropriate given the context, as opposed to the broader webster-merriam definition.

The picturebox guys Ren Rege, CF, Ben Jones, work more from comics in a fine art context, rather than comics in a literature context, which is what I’d guess Hilary Chute is coming from.

>> my apologies if i made you (or anyone else) feel old, it was not my intention.>>

You don’t have to worry about my feelings; I didn’t say you made me feel old. I said that if they’re currently active in the field, they’re contemporary.

That’s the definition Chute is clearly using, too, when she says “these people are doing fascinating and game-changing work right now.”

kdb

Comments are closed.