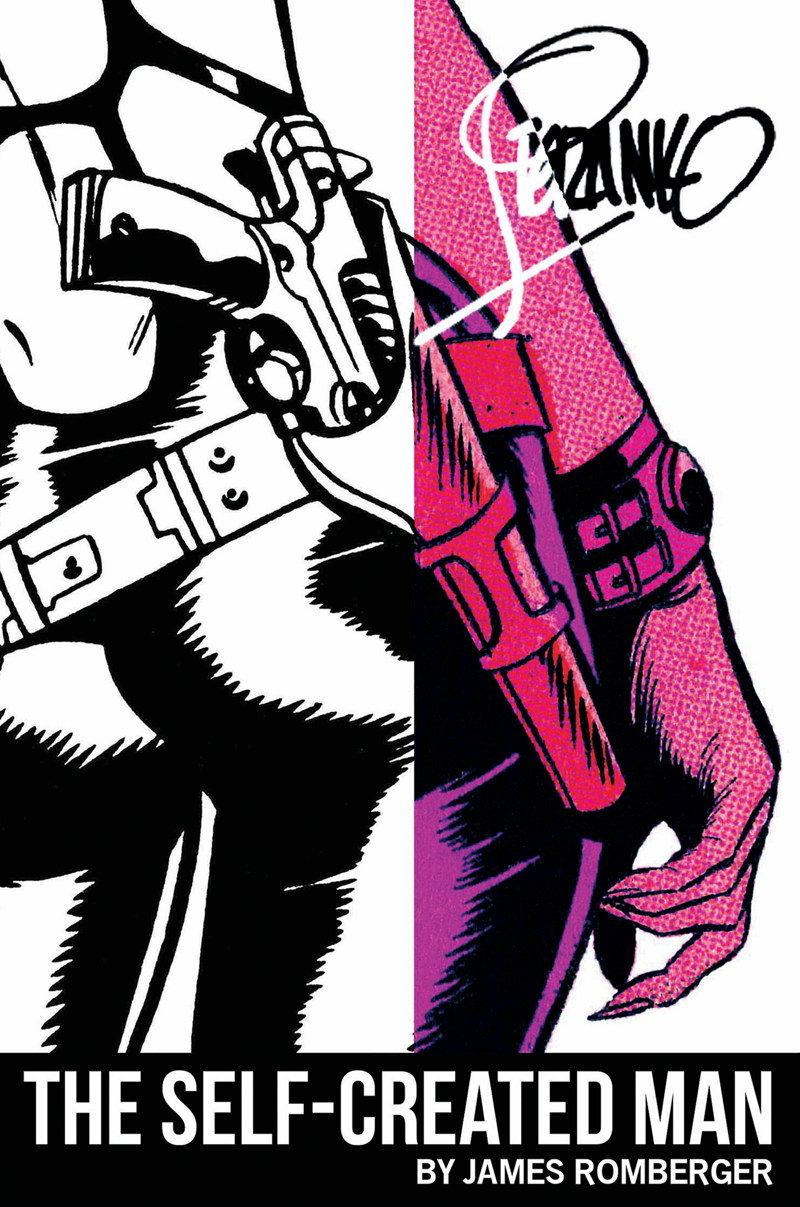

James Romberger is best known as the comics artist behind books like 7 Miles a Second, The Late Child and Other Animals, Post York, 2020 Visions and other books. He’s contributed to World War 3 Illustrated, Mome, and Epic Illustrated, and his artwork is in numerous museums including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. He’s also a writer and critic for publications including Publishers Weekly, The Comics Journal and here at The Beat. His new book is Steranko: The Self-Created Man.

The book consists of a long interview with comics creator Jim Steranko along with two essays covering different aspects of Steranko’s career in comics and film. Steranko is best known for comics like Nick Fury, Agent of SHIELD and Chandler: Red Tide. He’s worked in film on projects like Raiders of the Lost Ark, Dracula, and many never filmed projects with Alain Resnais, Francis Ford Coppola and others. Romberger and I spoke about the book, how he thinks about Steranko’s work and publishing through Ground Zero Books.

ALEX DUEBEN: James, I will admit the biggest problem that I had with the book was that I don’t have all the Steranko comics so I couldn’t follow along as you were talking about the books.

JAMES ROMBERGER: I couldn’t use as many illos as I would have liked to because I didn’t want to have to ask Marvel/Disney for permission or involve them in any way. Instead, I stuck with a limited amount of images that I could be sure really didn’t exceed fair usage. So the interview will make a lot more sense to the reader if they have all of Steranko’s work to refer to as they go though it – most of it is in print in some form. The two essays don’t need any backup, though.

DUEBEN: You mention in the book that the first Steranko you read was Strange Tales #163. What comics had you been reading and what was it about Steranko’s work that struck you at the time?

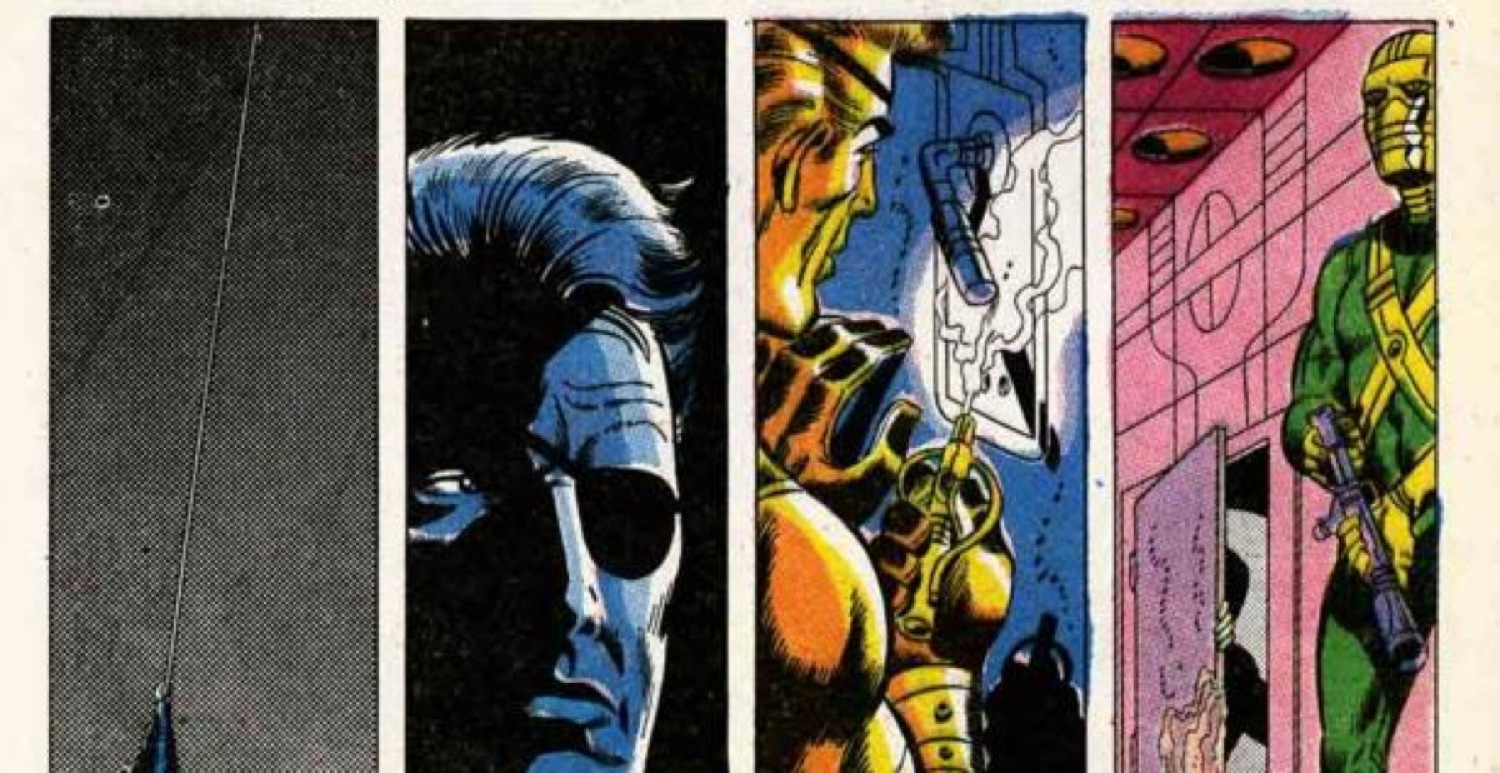

ROMBERGER: As a child who would sit comfortably with a stack of comics that included a range from Superboy to Archie and Baby Huey, I just didn’t differentiate that much; I liked comics. I didn’t like Neal Adams at that time, his DC art had a depressing adultness about it – although, I noticed how good Alex Toth was right away. But by 1967, I had begun to enjoy Jack Kirby’s magnificent art and the much darker tone of the Marvel books. I was already aware of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper and other manifestations of psychedelia and Steranko brought that sensibility into comics in a major way. In this issue, the splash page is like a Fillmore poster, then there’s the blue/green underwater escape scene, a great full page drawing of an ornate dragon statuette and that dark page of the old bomb maker – followed by the striking negative closeup and chromatic sequence with Fury passing out – incredible stuff which was far weirder and more ambitious than any comics I’d seen before. One very unusual thing was that unlike almost every other comic, the color was actually well done and integral to the story.

I guess what stood out to me was that Steranko was credited with story and art, which was unique – and then also the color was SO unusual that although it wasn’t credited, seeing a few more comics by this guy it became obvious that he was doing that too – which was VERY significant to me. To this day I consider color to be of paramount importance to the whole – and that makes it all the more ridiculous that so many people involved in comics are idiots in that regard; it is still the bottom rung on the ladder, low-paid and badly handled.

DUEBEN: Where did the idea of cataloguing all of Steranko’s innovations in comics come from as the idea to shape and guide the conversation?

ROMBERGER: Two Canadian academics who curated a Steranko exhibition in Winnipeg in 1978 had claimed they found 73 unique narrative devices in his Marvel work, but they did not detail them specifically. When Steranko realized how well I knew his work and he got a sense of the sorts of questions I was asking him, he asked me to do a methodical approach to all of his comics work to articulate his innovations.

DUEBEN: What was it about Steranko and his work that made you think this isn’t an article, because you’ve written plenty, but that there was so much ground to cover and it was interesting enough that this should be a book?

ROMBERGER: I hadn’t written much at all when I started in 2002. I did the interview with Jim intending to make it the main focus of the 3rd issue of a comics zine that Marguerite Van Cook and I were doing for fun, Comic Art Forum. But then it felt like it was so significant, and presented such a good opportunity to establish language for comics scholarship to be able to talk about the dovetailing relationship of art and text in comics, that I thought I’d try to get it done by a major publisher as a book. It seemed to need a biographical intro, which at the time I didn’t have the writing chops to do properly. At that point, one thing led to another and I returned to college at BMCC, then Columbia and CUNY Graduate Center. I spent a decade and a half completing my masters because I drew five books worth of comics and a few gallery shows in that time. Drafts of both of the essays in the book were originally done as papers for classes. The critical analysis training I got led me to writing for Publishers Weekly, The Comics Journal, etc. – and to teaching. So it has been a journey that took me to some unexpected places.

Just to note, I had originally counted 200 unique graphic and storytelling devices for our “Innovations” list that runs through the interview, but between Jim and I, we weeded out around a quarter of those as having been previously done by others – so Steranko was quite active in trying to not take undue credit for himself. And I retained my independence in writing the essays and assembling the book so it would have critical validity, rather than being an “approved” publication.

DUEBEN: You at one point jokingly ask if we should blame Image Comics on Steranko – in the worst 1990’s sense of that phrase – but so many of his innovations have become, if not commonplace then at least part of the standard toolbox of comics creators.

ROMBERGER: Image at that time was Spawn and those type of superhero books, all splash and little story, not like the more experimental Image now. By now many of the sorts of whole-page and double-page spread layouts and time breakdowns that Steranko did have been assimilated so deeply that some of the younger cartoonists think their sources are artists who borrowed them from Jim. And then there are the “homages” like the endless reuses of his SHIELD covers, which for some are genuine tributes and for others, it seems to me, indicative of laziness and a lack of their own ideas. I really wanted this book to clarify exactly what Steranko did and just how widely his influence has manifested in the culture.

DUEBEN: You mentioned Emma Rios as someone who’s working in really dynamic ways, but are there others who you see as influenced by Steranko or working in the same spirit and approach that he was?

ROMBERGER: I don’t see anyone experimenting to that degree. Earlier in his career, Art Spiegelman took risks sort of along those lines and so I consider Art to be one of Steranko’s greatest descendants. Of course, Jim is hugely influential and widely “homaged” i.e. copied in the mainstream. For instance Frank Miller deals with the sort of double-spread storytelling Steranko pioneered in “Outland” – but outside that, there are people trying different things: Gary Panter activated mark-making; Jaime Hernandez plays with time effectively; Chris Ware experiments with page design; Dash Shaw does odd color work; Marguerite and I also try to take content and color further and we have many more female cartoonists like Rios, Tillie Walden, Eleanor Davis, Jillian Tamaki et al. who are bringing a much wider range of sensibility and risk-taking on various levels to the medium, etc. But Jim is still a singularly innovative talent in what he has done.

DUEBEN: I was fascinated that Steranko worked with Alain Resnais for years on a film project. I know Resnais worked with Stan Lee on a film and made a movie with Feiffer, so he clearly loved comics, but Steranko in so many ways feels like he approached time and perspective in his comics similar to how Resnais did in film.

ROMBERGER: I think the DeSade film that Resnais and Jim worked on together went further and would have been more significant than the Lee-related projects the director was thinking of, that never happened—those seemed more lightweight genre exercises. I mean, it is a little odd that in the film essay, I cover so many unmade movies, but I wanted to show clearly how Jim’s collaborations with directors differed from his auteur practice in comics.

DUEBEN: In comics Steranko wants to be in control, but he’s very collaborative in his film work. Did you ask him about this or have a sense of how he thinks about these things?

ROMBERGER: I didn’t ask him that, but I can say that given the nature of movie production and the amounts of money involved in even the smallest indy film, much less a major feature – the ONLY way to work in film is collaboratively. Everyone including those at the top of the food chain, the producers, directors and stars, are dependent on the efforts of many other people. Even so, what I wanted to make clear in my essay was how very important Steranko’s input was to all of the films he has worked on, the ones that never made it to the screen as well as the finished ones.

DUEBEN: You also make it clear that there are problematic aspects to Steranko’s work and his ideas. There are conservative and retrograde ideas in there. He’s not Steve Ditko, but in a lot of ways he’s like so many artists of his generation and the previous one.

ROMBERGER: I think that Steranko is not conservative in the extremely repressed way that Alex Toth was, where it crippled him so much that he couldn’t work – or like Ditko’s absurdly blindered Libertarian obsessions. I mean, I can’t speak for his beliefs – but I think he is largely progressive in many ways. But he is a sort of NRA “stand-your-ground” guy because in his life he has had to defend himself. And then he reacted to the murder event of 9/11 in the same way as most Americans did because they accepted the narrative given by the media and the Bush administration – and similarly, he supported Trump like a lot of Americans do, because there are problems here that no one is addressing properly, that a gangster con man like Trump can exploit with their lies. But this risks also excusing the rest of the 30-some per cent of the U.S. that forms Trump’s base, so it is problematic for me. I address it in the book.

DUEBEN: I keep thinking about Steranko is important for you because you’re an artist who loves comics and makes comics, but like Steranko you haven’t spent your life drawing comics. You’re interested in artists who do many things and want to do many things.

ROMBERGER: Yes, he had been a role model for me in retaining control of my output and not putting up with bullshit. In 2003 or so he advised me to do some mainstream work in comics to raise my professional profile and I followed that advice; but I’m not sure it worked, at least partly because the books I did at that time had narrative problems that I wasn’t in a position to fix. Then when I shifted back to the alternative, the content problems weren’t there, but there were other issues, of lack of recompense, of promo and distribution. Steranko also dealt with those, and before most of us. But also he is a good example of not always having all of your eggs in one basket. He rarely depended on comics to be his main act.

DUEBEN: The book is published by your own Ground Zero Books. Why did you decide to make this imprint and publish Steranko through it? And what are your plans for Ground Zero beyond this?

ROMBERGER: I guess that reflects another thing Steranko stands for: if you want it done right, do it yourself. Marguerite thought it was time for us to self-publish when Fantagraphics let 7 Miles a Second go out of print just as the Whitney Museum mounted their huge retrospective exhibition of David Wojnarowicz. When that went well, she suggested doing the Steranko book, which was a way around the fact that Steranko and I have had one issue or another with maybe every other publisher that seemed likely to want to print it. We are now considering various further projects, including publishing others’ work.

DUEBEN: For people who read this interview or read the book, where should they start? Whether in print or not. There’s a lot I haven’t read.

ROMBERGER: The original vintage comics can be quite expensive unless you can find dog-eared reading copies, like I have. But much of his work is available in reprint from from Marvel, although the color (which is so important) can be iffy in those. I’d also recommend getting used copies of Chandler: Red Tide on Ebay or Amazon and finding the Heavy Metal issues where Outland was serialized.

DUEBEN: Is there a chance we’ll see reprints of a lot of Steranko’s work? Or new Steranko comics one of these years?

ROMBERGER: As I say, Marvel keeps most of his work for them in print. I think that Chandler should be reprinted in facsimile form by someone with a brain while Steranko takes his sweet time on his digital recoloring of the Dark Horse version, and a trade paperback of Outland would be nice. I don’t know who owns the rights. He did a major short story for Marvel called Dante’s Inferno that still hasn’t been published! And I think that for all these years he would have done great comics, if only the damned fool companies would offer him the payment he deserves and the sort of “final cut” deal that they regularly give people who know a hell of a lot less about what they are doing. I think he has plenty of ideas. They still could! We can dream.

DUEBEN: You’re always in the midst of a few different projects and you’re always drawing a new comic. What are you working on now?

ROMBERGER: I am working on a deal with a major publisher to print a full graphic novel of Post York, which incorporates the comic book/flexidisc that my son Crosby and I did a few years back with Uncivilized Books, and I am almost done with the new pages for that – but I don’t want to say more because I don’t want to jinx it! Meanwhile I am also working on another, completely different 20 page story that will be paired with a short connected essay, to be a one-shot floppy comic for the upcoming new line of serial comic books that Tom Kaczynski is producing for Uncivilized.

You can order Steranko: The Self Created Man here.

I’m curious to know if Steranko talks at all about his 2-volume Steranko History Of Comics (and why further volumes never saw the light of day.)

This looks really great!

herrdoctorffej, I did ask Steranko about future volumes of the History of Comics and got a brief reply—but beyond that, I would say that we are lucky that we got two volumes of the project from such a multi-talented perfectionist whose fingers were in so many pies, then and still.

Those “History of Comics” books were my introduction to the Golden Age (and to pulps and classic newspaper strips). I still cherish them.

Comments are closed.