By Victor Van Scoit

Roaming around Austin during SXSW is a perfect way to stumble into discoveries. One such find this year was the Nordic Lighthouse—a showcase of Nordic startup tech, cinema, music, food, and design. Lucky for me Simon Stålenhag, the author of Tales From The Loop, was part of that showcase.

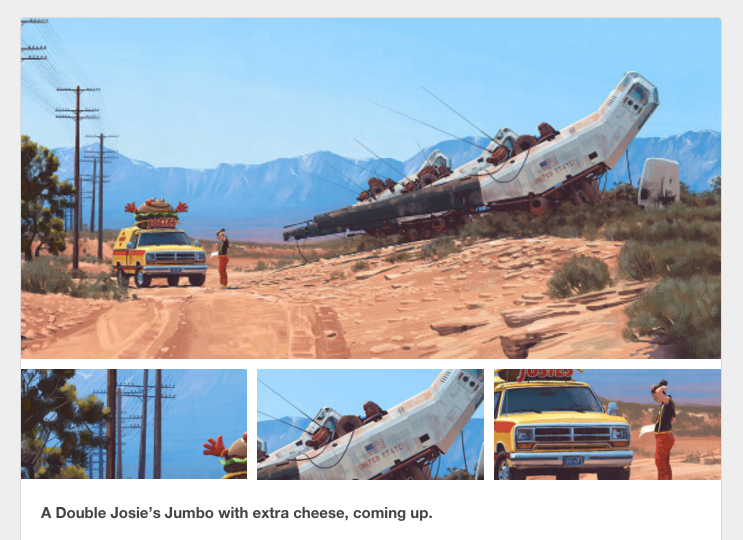

I was excited about speaking with Simon because about three years ago a series of his paintings went viral. They depicted an 80’s Swedish countryside where people lived their quiet lives alongside future tech and aging science relics. The juxtaposition was unique compared to they typical post-apocalyptic and dystopian takes on science fiction. He later took those paintings and wrote a narrative that was released as Tales From The Loop in Sweden. Later with a Kickstarter campaign he was able to release an English translation for us to enjoy.

The vibe was right at the Nordic Lighthouse as music acts played the outdoor stage, Swedish food was served from a food truck, drinks were being shared, and many enjoyed the river view. Simon wasn’t sure what to expect at SXSW, but he was in good spirits and had embraced the chaos of SXSW that allows for serendipity. A rare appearance for him stateside I couldn’t pass up the opportunity for a conversation about his work and inspirations.

Victor Van Scoit: We were talking downstairs earlier about, ah, forgive me I just blanked on it… the loop!

Simon Stålenhag: The loop, yeah, Tales From The Loop.

VVS: It’s not new, but it is new to a lot of people still. The first time I ever saw it there were some images that looked creepy in that they were familiar—even though they merged future tech in a normal world of today. Every picture that you had, which at first I thought were photographs, felt like they told a complete story. I was actually surprised they were painted. You mentioned that in the book you can see the brush strokes.

SS: You can do it on the website too. On my website I always upload the full image and close ups so you can see interesting parts of the composition. Then you see the brush strokes. It actually is pretty simple. I don’t try to render too many details. I keep the details where it matters and so it’s quite loose actually.

VVS: That’s what’s amazing to me. Each image I saw, while they might not be detailed by your creative execution, to me they’re detailed enough that it creates a story that make me ask “What’s next?” Was there always a story or did you create a story once people starting connecting with the pictures online?

SS: No. It was three years ago that it kind of went viral overnight. I had been writing this for almost a year before—the stories. “Should I publish the text or should I not?” I even did a dummy website with the text because I really wanted to tell the story. But then I finally realized that the book form is the best form. For the online stuff it’s better if they just pose these questions and not have any text. They kind of have two lives. Online a lot of people don’t know the backstory. I think that’s good. For people who buy the book I present enough text to keep the mystery going. There’s some stuff I feel is important for me. The text itself is another art form. For instance the text was a starting point for me. There’s so many interesting Swedish words that haven’t been used in a science fiction context yet.

VVS: Sure.

SS: So I wanted to do that. Make up engineering terms that don’t exist in Swedish. Like technobabble? You hear it all the time in English, but how would it sound in Swedish? That was one of the inspirations for the text.

VVS: Some of the best sci-fi is when you present new terms for people to connect with.

SS: It’s interesting to see how it translated to English where it’s Swedish technobabble, translated into English technobabble. We kept a lot of the—some words aren’t translated at all because it’s almost like an exotic flavor if you have the original Swedish word.

VVS: Some of the best movies and books I’ve enjoyed contain words that are never defined, but through context you create your own feeling of what that word represents in the world

SS: The Tannhäuser Gate in Blade Runner

VVS: Ah yes!

SS: Tannhäuser is part of some Wagner, but it’s what Rutger Hauer says at the end of Blade Runner.

VVS: Yes! Classic. That’s what it is—that feeling.

SS: They never explain that but it’s like a German word or something and it blows your mind.

VVS: It leaves a mystery for other people to enjoy and interpret.

SS: Yeah! That’s the way to do science fiction. Basically, right there in those few words.

VVS: I’ve always felt that the best science fiction that people still recall, is enjoyable, or gets rediscovered is that stuff that leaves them with questions and not just answers. You mentioned the translation that has the Swedish technobabble. Did you do the translation?

SS: No.

VVS: How did you go about trying to find the right person?

SS: We have a Swedish guy. There’s basically two ways of doing it. You can either have an English speaker who knows the language and can find the emotional context.

VVS: I imagine that’s the most difficult. Not the direct translation, but understanding the emotional context.

SS: But then we have a guy who is a Swede who knows what these Swedish terms mean. He’s like one of the guys in the pictures [from Tales From The Loop]. I don’t know what the difference would be but in this case I think the Swedish cultural stuff is more important. Like right now I’m working on something else that might be set in the U.S. For that I almost feel that I need a collaborator that has that kind of familiarity. Because I become more like a scientist that looks at something from above.

VVS: Obviously you had a story to tell that was science fiction related, but were you also trying to expose people to the Swedish culture as well?

SS: Yeah I think that’s always something that I thought. Why hadn’t anybody done this the Hollywood way?

VVS: Yes. We already get the music and design. The music from Sweden is great with their spins on influences from western culture.

SS: Yeah.

VVS: It’s always interesting to see how people who grew up with western cinematic influences and how they interpret them for their area and their stories.

SS: That’s what I realized when all this went viral. Most people feel the same. People from, like Michigan, this looks like where I grew up. I think the settings are specific. They’re not generic. In E.T. they shot the house scenes in the San Fernando Valley, and they shot the forest scenes in the redwoods. Which is like a seven hour drive? I love that film, but that is not specific. There’s no place that looks like that in the real world.

VVS: Got it. There’s a sense of place but there’s no real place.

SS: There’s a house that’s here and in the real world you take a seven hour drive to get to the forest which he does on his bike in 20 minutes. It’s almost like a fairy tale and maybe that’s okay. But I like specific. This is a real place. Every angle and every viewpoint you can almost triangulate between images like with a camera that this feels like a real place. And I think that’s important.

VVS: It’s huge. I think the reason your images went viral was because most people when they think of science fiction in the modern day blended setting—it’s always in an urban environment. What was attractive was that you had a farm field with a kid playing outside that has equipment that looks like it came straight out of a Valve video game. That juxtaposition was both jarring and intriguing.

SS: Because you have to be convincing when you’re doing science fiction. there’s so many layers to a scene. Like this one picture where this kid goes with his snow sled and you see this short oat, some grain they grow there in Sweden. In the winter you have this—what do you call it when they’re cut?

VVS: The harvest.

SS: Yes, they’re harvested. You only have the thick…

VVS: The stalk? The portion remaining.

SS: Yeah, which sticks up in the snow. And that means something because if you see that, it means they harvested it like a couple of months before. There’s a functional agriculture going on. It’s not post-apocalyptic. All those details they kind of accumulate subliminally. So you feel that this is a real place that has a backstory. Even if you don’t know how it works you know that there’s something behind that. It’s very simple stuff. You just choose the right details and it becomes layered and it’s specific.

VVS: It’s textured.

SS: Yeah that makes it. In that picture it’s actually two huge wild boars with some kind of antenna sticking out of their back. That makes that thing much more scary.

VVS: I think it circle back to what you were saying earlier. The picture alone is texture and layered enough to tell a story. But why the narrative, the text, is also another art form unto itself.

SS: Yeah it’s separate.

VVS: They’re both together and separate—can be enjoyed separately or as one—two art forms that could live alone but together form a different narrative.

SS: Yeah, exactly.

VVS: What you’ve created feels unique.

SS: With that text I didn’t tell “And there’s this field with snow”. That’s in the picture so I told something else. In that particular text I wanted to say something about those wild boars. This research lab that all the kids were talking about that were trying to make machines that could reason. They had these experiments and these animals that they tried to remotely control. Something like that. That kind of prose. I was inspired by this Stephen King sci-fi/horror thing. I remember those Swedish translations of Stephen Kind, mind you, which had this kind of language that I wanted to get to. It said something about the focus of the image, but it didn’t describe the image in any way. They should be separate.

VVS: You let the reader fill in those gaps and the context. You don’t have to explain about the stalks and the harvest. They think “There must be more to that” and they start to ask those questions.

SS: That’s what I think is much more interesting doing something that is not post-apocalyptic and not set in a dystopia.

VVS: We do get a lot of post-apocalyptic. This was a little more inspirational in seeing what could happen when things go well in balancing future making and a future society.

SS: All this is is an extrapolation of the eighties and nineties. All the robots are designed if they were made in the eighties, or the seventies, or the sixties. And how stuff from the sixties looked in the eighties. If you saw trains in the eighties that are thirty years old and they have this kind of—what do you call it? Patina?

VVS: Yes exactly. A patina.

SS: I translated that into robots instead. So you get those kind of layers. This is an old machine. It still feels like old machines felt in the eighties. You see certain cars and you think that must be the eighties. I don’t go into detail about that in the book. It’s just something that present.

VVS: So obviously you’re a child of the eighties and nineties cinema?

SS: Yeah I was born in… ’84. I remember watching The Abyss

VVS: Oh yes.

SS: In like ’93, ’94 maybe. I mean there was kind of a time lag between when movies came out.

VVS: In Sweden vs the United States

SS: That too. Now you can get them on iTunes. But back then some friend had a film on VHS and you borrowed it and copied it.

VVS: That might have been one of the things that everyone not living in America got to benefit from back then. If something ever did make it abroad it already had gone through a filter indicating it must be good. People spent money to translate it, and if it wasn’t good it would make it over.

SS: No it wouldn’t

VVS: Much as with Japanese animation in the eighties when it would cover over here. It took effort to subtitle and copy and if it made it over that’s when you knew—”This is something precious”—and I’m going to absorb everything I can from it.

SS: Yeah exactly. Access to that kind of entertainment was limited so the stuff you had was very precious. I had Terminator, the first one, and Alien. I remember my father—I was too young to see it. I was like seven or eight. He told me the story like in a non-scary, but still very scary for me. He told me about it and I remember one of my bedtime stories for me is Alien which is weird.

VVS: (laughs)

SS: But that’s how it is.

VVS: As a nighttime bedtime story?!

SS: Basically he saw it when it came out in Sweden and my father loves to tell stories and he told me this story. Then when it was time for me to go to bed I was like “No. Tell me that story again.” So he had to retell that story many times. It became a bedtime ritual.

VVS: That’s great. It’s obvious that he was an influence in your own storytelling.

SS: Yeah, yeah. Obviously I always loved those science fiction stories and horror stories also.

VVS: That great. I discovered Tales From The Loop about three years ago, read the article, forgot about it. Then when I randomly saw you here I thought “Whoah it’s you!” I must have missed the updates and the Kickstarter and now there’s an English translation not just a Swedish translation. I missed out on that Kickstarter but what the best way for people to get it?

SS: You can pick it up on Amazon. No problem

VVS: Sweet. Is there a second book coming out?

SS: It’s coming. It’s definitely coming. We’re going to ship it and then it will be coming out on Amazon. It’s going to take a while. We’re going to print it in May. Everything takes time. But it’s written.

VVS: This seems like this came from an honest organic place. You weren’t trying to make a calling card to Hollywood. You were going to make this regardless.

SS: Yes. Very much.

VVS: But somebody has to be calling you now asking if you want to work on conceptualization, or do you want to make your own movie. Have those opportunities been presented to you?

SS: Yeah sure. I’m very cautious. I get some scripts. Most of them are—why do they make these kind of films. They should be making… and then I made this book.

VVS: There’s a reason why you followed your own creative vision versus someone else’s.

SS: I’m very lucky that this happened to me. That it became viral and people saw it and that people like it and tell there friends about it. If nothing else it just gave me the time to do more. More of it. Film is really a big passion. The reason I never tried to become a filmmaker is because I have such respect for it. There’s so many people that shouldn’t have become filmmakers. (snickers)

VVS: Yes. We’re very much in a remake society—

SS: Yeah.

VVS: with some franchises—

SS: Yes

VVS: and I’ve always wondered why they’re remaking the movies that were good. Why aren’t we remaking the movies that didn’t do well but had a great premise.

SS: Yeah exactly!

VVS: There was obviously a good premise, but it was just executed poorly. Let’s remake that one.

SS: Yeah instead of ruining something that’s already good. That’s true. I never thought about that.

VVS: To me, in your situation, if you were presented with something that had a good premise but was executed poorly that might set of your curiosity.

SS: Yeah exactly. I get this generic stuff. I’m not even sure if in the end they would let me do it. It’s almost like I’m given a chance to do something, but it’s obvious that I shouldn’t. It’s not the right way to go. I didn’t make this book to get the chance to make a crappy movie.

VVS: No. Take your time. Take your shot wisely.

SS: I’m going to Los Angeles tomorrow.

VVS: Fantastic

SS: I’m going to meet with people.

VVS: I personally like to find cool stuff like yours and recommend it to other people. Is there anything you’ve found here at SXSW or anywhere else that you would say to check this out—this artist, this movie, something people aren’t aware of?

SS: I really have to force myself to look at contemporary stuff.

VVS: You enjoy revisiting older stuff.

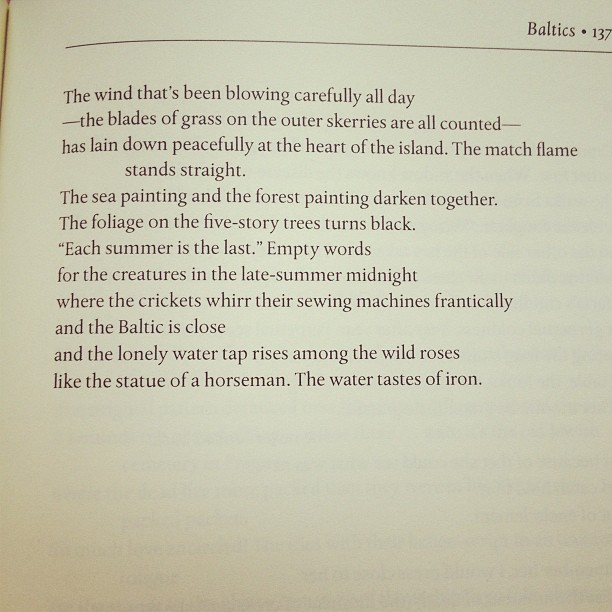

SS: The stuff that influences me is really old Swedish naturalist painters and writers and poetry. It’s very hard to say you really need to check this out. There is already an audience for that, but maybe I want another audience to see it.

VVS: There’s new and shiny, but it also doesn’t mean you can’t have something old and have a patina that’s attractive. What’s one of those books or poets that you enjoyed?

SS: Tomas Tranströmer. He’s a Swedish poet that won the—is it the Nobel?

VVS: Nobel prize

SS: I don’t know if that’s what he won, but maybe it is. He’s a Swedish poet and he’s translated by a guy called Robert Fulton. They are friends. That’s how it has to be.

VVS: Yes, it goes back to what you mentioned earlier. When you find a translator you need one that understands the cultural contexts.

SS: Thomas Tranströmer was visiting the U.S a lot and there was a transatlantic connection there. I have the English translation and we use that. In the Swedish version of the book [Tales From The Loop] we had a quote in the beginning which we didn’t want to translate because it was so poetic. It wasn’t a poem, but it was very poetic. We didn’t want to translate it ourselves and I had these Tomas Tranströmer translations. I looked one up that fit with the book because then I knew the author has approved of this translation.

VVS: You definitely hold it with a certain amount of reverence.

SS: Yeah that guy. Tomas Tranströmer I try to quote some of his poems on my Tumblr. That’s the nice thing about Tumblr or a Twitter. You can push things out and say “Look at this poem. It goes with this picture”

VVS: Thanks for sharing. It’s good to remember you can get inspired from many places. So how do people keep up with you best?

SS: My website you can find my Twitter and Tumblr. I don’t have Instagram. I don’t know if I should. (laughs)

VVS: Instagram is nice. The reason I like it is it seems to take more effort for people to be mean and angry on there. So there’s less of that.

SS: When it comes to art people seem to be nice in general. I’ve never had any bad. It’s when it becomes political.

VVS: Thanks so much for your time. Good luck in L.A.

Simon Stålenhag is an acclaimed artist, concept designer, author and illustrator. You can see more of his work and cinematic images on his website and tumblr.